Sebastiano Luciani, known to history as Sebastiano del Piombo, stands as a pivotal figure in the Italian High Renaissance. Born in Venice around 1485, his life and career bridged the two dominant artistic centers of the era: the color-rich environment of his native city and the monumental classicism of Rome. His journey from a promising musician to one of the most sought-after painters in Rome is a tale of ambition, collaboration, rivalry, and artistic synthesis. Sebastiano ultimately forged a unique style, blending the sensuous color and atmospheric effects of the Venetian school with the powerful drawing and compositional grandeur characteristic of Central Italian art, leaving an indelible mark on the course of Western painting. His friendships and rivalries with giants like Michelangelo and Raphael further place him at the heart of the artistic ferment of the early 16th century.

Venetian Foundations: Color and Atmosphere

Sebastiano's artistic journey began not with a brush, but likely with music, as he was initially known as a talented lute player. However, the vibrant artistic atmosphere of Venice soon claimed his full attention. He entered the workshop of the aged but still highly influential Giovanni Bellini, the patriarch of Venetian painting. Under Bellini, Sebastiano would have absorbed the fundamentals of oil painting technique, particularly the meticulous layering of glazes to achieve depth, luminosity, and rich tonal harmonies – hallmarks of the Bellini studio that profoundly shaped Venetian art.

His training, however, coincided with the meteoric rise of Giorgione, another transformative figure who may also have been Sebastiano's teacher or, at the very least, a profound influence. Giorgione's enigmatic, poetic style, characterized by soft contours (sfumato), evocative landscapes, and a mastery of mood and atmosphere, captivated the younger generation. Sebastiano quickly assimilated these elements. His early works, such as the organ shutters for the church of San Bartolomeo di Rialto (circa 1508-1509) and the altarpiece of St. John Chrysostom with Saints for the church of San Giovanni Crisostomo (begun perhaps by Giorgione, completed by Sebastiano circa 1510-1511), demonstrate this burgeoning synthesis. They reveal a Giorgionesque sensitivity to mood and landscape, combined with a Bellinian solidity of form and a burgeoning interest in psychological presence, particularly evident in the powerful figures of the saints. In this dynamic environment, Sebastiano was a contemporary of Titian, another pupil emerging from the Bellini/Giorgione milieu who would come to define Venetian painting for decades. The early careers of Sebastiano and Titian show parallel developments, absorbing the lessons of their masters while forging individual paths.

The Call to Rome: Agostino Chigi and the Farnesina

The turning point in Sebastiano's career came in 1511. He was summoned to Rome by Agostino Chigi, an immensely wealthy Sienese banker and patron of the arts, who was then constructing and decorating his lavish suburban villa, now known as the Villa Farnesina. This move thrust Sebastiano from the relatively self-contained world of Venice into the epicenter of the High Renaissance, a city buzzing with artistic energy under the ambitious patronage of Pope Julius II. Rome was where artists grappled with the legacy of classical antiquity and where monumental fresco cycles were the ultimate measure of artistic prowess.

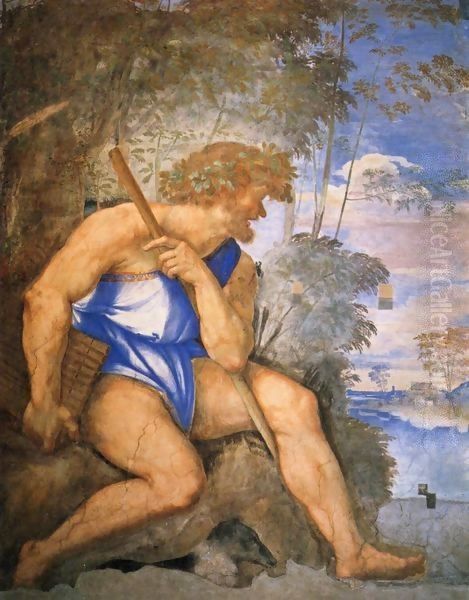

Chigi's Villa Farnesina was a showcase project, attracting the brightest talents. Sebastiano was commissioned to paint mythological scenes, working alongside renowned artists like Baldassare Peruzzi, who designed the villa and painted the ceiling frescoes in the Salone delle Prospettive, and, most significantly, Raphael. Sebastiano's contribution included lunettes depicting mythological scenes and, most notably, the figure of the giant Polyphemus (circa 1512) in the Loggia di Galatea. This powerful, somewhat brooding figure already hints at Sebastiano's inclination towards weighty forms, even as it retains a Venetian sensitivity to color and texture. Working in Rome exposed him directly to the dominant artistic currents of Central Italy – the emphasis on drawing (disegno), anatomical precision, and complex, dynamic compositions inspired by both ancient sculpture and the burgeoning genius of Michelangelo.

Raphael: Rivalry and Respect

Sebastiano's arrival in Rome inevitably placed him in the orbit of Raphael Sanzio da Urbino, who was then at the height of his fame, dominating papal commissions with his workshop, including talented pupils like Giulio Romano and Perino del Vaga. At the Villa Farnesina, Sebastiano's Polyphemus was painted adjacent to Raphael's celebrated fresco The Triumph of Galatea (circa 1512). The juxtaposition highlights their differing approaches: Raphael's dynamic, graceful composition, full of light and movement, contrasts with Sebastiano's more static, massive, and psychologically intense figure.

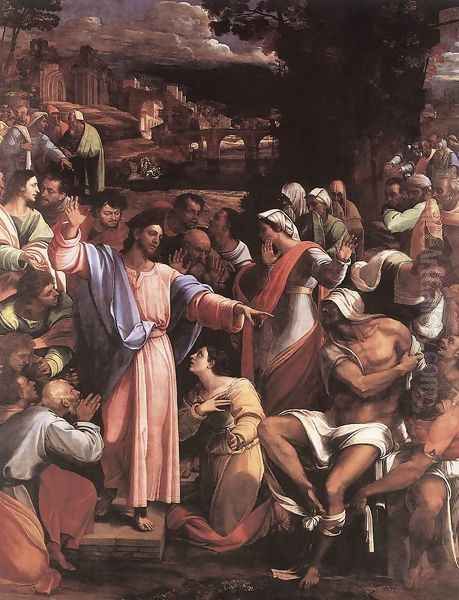

While there may have been initial collaboration or at least professional coexistence, a potent rivalry soon developed. This was famously crystallized in a commission from Cardinal Giulio de' Medici (later Pope Clement VII) around 1517 for two large altarpieces destined for Narbonne Cathedral in France, of which the Cardinal was bishop. Raphael was commissioned to paint The Transfiguration, while Sebastiano was tasked with The Raising of Lazarus. This direct competition became a major event in Roman artistic circles. Sebastiano, aware of the challenge posed by Raphael's mastery of composition and drawing, turned to his friend Michelangelo for assistance. Michelangelo, who harbored his own complex rivalry with Raphael, provided drawings, particularly for the figure of Lazarus, lending his formidable power of anatomical expression and dramatic intensity to Sebastiano's work. The resulting painting, now in the National Gallery, London, is a masterpiece of synthesis: Michelangelo's powerful forms are clothed in Sebastiano's rich Venetian color, dramatic lighting, and atmospheric depth. Although Raphael's Transfiguration (now Vatican Museums) was ultimately judged the superior work upon its completion (after Raphael's death in 1520), Sebastiano's Lazarus established him firmly as a leading painter in Rome, capable of operating at the highest level. The rivalry, though perhaps fueled by patrons and artistic politics, spurred both artists to produce works of extraordinary power and innovation. Sebastiano was even reported by contemporaries, perhaps somewhat defensively, to have accused Raphael of plagiarizing elements from his own work.

Michelangelo: Friendship and Collaboration

The relationship between Sebastiano del Piombo and Michelangelo Buonarroti is one of the most fascinating artistic partnerships of the Renaissance. Beginning shortly after Sebastiano's arrival in Rome, it developed into a close friendship and a unique form of collaboration that lasted for over two decades. Michelangelo, primarily a sculptor and fresco painter, recognized Sebastiano's exceptional talent as an oil painter, particularly his mastery of Venetian color and sfumato. Seeing an opportunity to compete indirectly with Raphael's dominance in painting, Michelangelo began providing Sebastiano with drawings, sketches, and compositional ideas (invenzioni) for major commissions.

This collaboration allowed Michelangelo's powerful conceptions of form and drama to be realized through Sebastiano's painterly medium. The Raising of Lazarus was a prime example, but other significant works resulted from this synergy. The Pietà (circa 1512-1516) for the church of San Francesco in Viterbo is one of the earliest and most moving examples. Based on Michelangelo's designs, Sebastiano created a work of profound pathos, where the sculptural solidity of the figures is softened by the subtle gradations of light and color, creating an atmosphere of deep mourning unique to Sebastiano's hand.

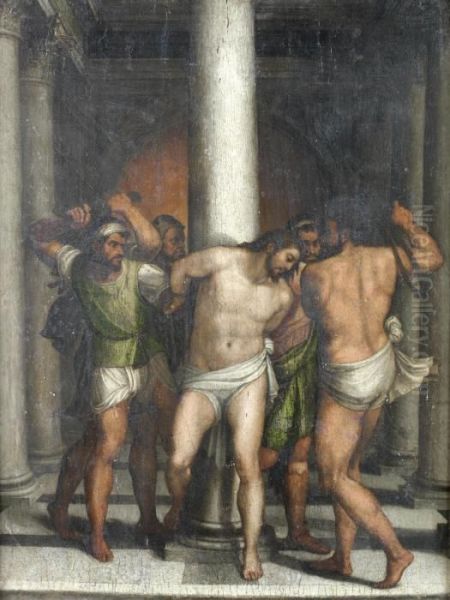

Another major collaborative project was the decoration of the Borgherini Chapel in the church of San Pietro in Montorio, Rome (commissioned around 1516). Sebastiano painted the monumental Flagellation on the main wall, again likely using drawings provided by Michelangelo for the central figures. He also executed flanking figures of prophets and sibyls. The Flagellation is a powerful nocturnal scene, showcasing Sebastiano's skill in rendering dramatic light effects and rich textures, while the figures possess a Michelangelesque weight and energy. Works like Christ Carrying the Cross (versions in the Prado, Madrid, and Hermitage, St. Petersburg) also likely benefited from Michelangelo's input. This partnership was mutually beneficial: Sebastiano gained access to Michelangelo's unparalleled inventive genius, enhancing the intellectual and formal power of his work, while Michelangelo found a painter capable of translating his ideas into compelling oil paintings that could challenge Raphael's supremacy. Their friendship is documented through correspondence, revealing mutual respect and affection. However, according to the biographer Giorgio Vasari, the relationship eventually soured dramatically in the 1530s over the preparation of the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel for Michelangelo's Last Judgment. Sebastiano, an advocate for oil painting, had prepared the wall for this technique, but Michelangelo insisted on traditional fresco and reportedly never forgave Sebastiano, leading to a permanent break.

Forging a Mature Roman Style

Working in Rome, absorbing the lessons of antiquity, Raphael, and especially Michelangelo, Sebastiano forged a mature style that was uniquely his own. He successfully integrated the Venetian emphasis on colore (color, light, atmosphere, texture) with the Central Italian emphasis on disegno (drawing, composition, sculptural form). His paintings from the 1510s and 1520s demonstrate this powerful synthesis. He retained the deep, resonant colors and subtle atmospheric effects learned in Venice, but applied them to figures possessing a new monumentality and physical presence, often arranged in complex, dynamic compositions learned in Rome.

His religious paintings became imbued with a profound gravity and emotional intensity. Beyond the Pietà and the Raising of Lazarus, works like the Martyrdom of Saint Agatha (Pitti Palace, Florence) or the Visitation (Louvre, Paris) showcase his ability to convey dramatic narratives with psychological depth. He excelled at depicting rich fabrics, reflective armor, and the play of light on surfaces, lending a tangible reality to his scenes. Yet, this realism was always combined with an idealized grandeur, particularly in the depiction of the human form, which often shows the muscularity and heroic proportions associated with Michelangelo. He became, after Raphael's death in 1520, arguably the leading painter in Rome, sought after for major altarpieces and devotional works. His style represented a compelling alternative to the classicism of Raphael's followers, offering a more emotionally charged and painterly vision.

Master of Portraiture

Alongside his large-scale religious works, Sebastiano excelled in portraiture, becoming one of the most sought-after portraitists in Rome. His Venetian training, with its emphasis on capturing likeness through light and color, combined with his Roman experience in conveying gravitas and psychological presence, made his portraits highly prized. He painted popes, cardinals, aristocrats, humanists, and fellow artists, leaving behind a gallery of the powerful and influential figures of his time.

His portraits are characterized by their sober realism, psychological insight, and often imposing presence. He typically employed a limited palette, focusing on subtle tonal variations and the play of light to model form and suggest texture. Unlike the often idealized portraits of Raphael or the more overtly opulent style sometimes favored by Titian, Sebastiano's portraits convey a sense of introspection and authority. Notable examples include the imposing Cardinal Bandinello Sauli, His Secretary, and Two Geographers (National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.), the commanding portrait of the Genoese admiral Andrea Doria (Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome), and several portraits of Pope Clement VII (e.g., Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Museo di Capodimonte, Naples), capturing the pontiff's troubled mien during a difficult period. He also painted intellectuals like Pietro Aretino (Palazzo Comunale, Arezzo) and noblewomen such as Giulia Gonzaga (often identified with a portrait in the National Gallery, London). His supposed portrait of Christopher Columbus (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), though its subject is debated, exemplifies his ability to create a powerful and memorable image. Sebastiano's portraits stand alongside those of Raphael and Titian as defining achievements of High Renaissance portraiture, valued for their blend of realistic depiction and psychological depth. His approach influenced later portrait painters, particularly in Rome and Spain.

The Office of the Piombo: A Turning Point

A significant shift occurred in Sebastiano's life and career in 1531. Following the death of the previous holder, Pope Clement VII appointed him to the lucrative and prestigious office of Piombatore Pontificio (Keeper of the Papal Seal). This position involved affixing the lead seal (piombo) to official papal documents and bulls. It provided considerable financial security and status, and it was from this office that Sebastiano derived the name by which he is best known: "del Piombo."

However, the appointment came with conditions. The office required the holder to take holy orders, specifically becoming a friar. Although Sebastiano was married and had children, he accepted the position and took the vows, becoming Fra Sebastiano. This decision had profound consequences for his artistic output. The demands of the office, combined with the comfortable income it provided, seem to have significantly reduced his inclination or perhaps the time available for painting. Giorgio Vasari, in his Lives of the Artists, famously remarked that the security of the office made Sebastiano somewhat complacent, suggesting he enjoyed the comforts of life more than the rigors of artistic labor. While this might be a simplification, it is undeniable that Sebastiano's production of paintings slowed considerably after 1531. He undertook fewer large-scale commissions and seemed to work at a more leisurely pace. This shift marks a distinct later phase in his career, where his role as a papal official perhaps overshadowed his identity as a painter, at least in terms of prolific output.

Later Works, Technical Experiments, and Style Evolution

Despite the reduced output, Sebastiano continued to paint after accepting the Piombo office, and his later works show interesting developments. His style arguably became darker and more somber, perhaps reflecting personal introspection, the traumatic experience of the Sack of Rome in 1527 (which deeply affected the city and its artists), or the changing spiritual climate of the Counter-Reformation, which increasingly favored emotionally direct and pious religious art.

One of the most notable aspects of his later career was his experimentation with painting techniques, particularly the use of oil paint on stone supports, such as slate and marble. This was partly driven by a desire for permanence, as oil on stone was less susceptible to damage from humidity or fire than oil on panel or canvas. It also allowed for a different kind of luminosity, as the dark, smooth surface of the slate could enhance the richness and depth of the oil colors. Several important late works were executed on stone, including portraits like the aforementioned Clement VII (Naples version on slate) and religious works like variants of Christ Carrying the Cross. The Birth of the Virgin (Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome) is another significant late work on stone (peperino). These works often possess a polished finish and a cool, enamel-like surface quality. While technically innovative, this technique was laborious and contributed to his slower pace of production. His late style, characterized by dark backgrounds, dramatic lighting, and intense, often melancholic figures, shows a move away from High Renaissance balance towards Mannerist expressiveness, aligning him with contemporaries like Bronzino in Florence, though Sebastiano always retained a unique Venetian warmth even in his most austere compositions.

Legacy and Influence: Bridging Artistic Worlds

Sebastiano del Piombo's legacy lies in his unique position as a conduit between the Venetian and Roman schools of painting during one of the most dynamic periods in art history. He successfully absorbed the defining qualities of both traditions – the sensuous color and atmospheric light of Venice, and the monumental form, intellectual rigor, and dramatic power of Rome – creating a synthesis that was entirely his own. His collaboration with Michelangelo resulted in some of the most powerful religious images of the High Renaissance, demonstrating how the strengths of two distinct artistic personalities could merge to create something new.

His portraits set a standard for psychological depth and dignified realism that influenced subsequent generations. His technical experiments, particularly with oil on stone, showcased his innovative spirit. Although his fame was somewhat eclipsed by the towering figures of Raphael, Michelangelo, and Titian, and his later career was less productive, Sebastiano was recognized by his contemporaries as a major force. He played a crucial role in the artistic life of Rome for over three decades. After Raphael's death, he was the city's preeminent painter, particularly favored for his portraits and his emotionally resonant religious works. His influence can be seen in the work of later Roman painters and potentially extended to artists visiting Rome, including those from Spain, like perhaps El Greco, who would have encountered his powerful synthesis of color, light, and form. Giorgio Vasari's biography, while critical of his later perceived indolence, nonetheless confirms his high standing.

Conclusion: A Venetian Master in Rome

Sebastiano Luciani, Fra Sebastiano del Piombo, died in Rome in 1547. His career spanned the golden age of the High Renaissance and the beginnings of Mannerism. From his formative years absorbing the lessons of Bellini and Giorgione in Venice, through his arrival in the competitive artistic crucible of Rome, his complex relationships with Raphael and Michelangelo, his rise to prominence as a master of religious subjects and portraiture, and his later years balancing artistic creation with papal office, Sebastiano carved a unique and significant path. He demonstrated that the painterly richness of Venice could be powerfully fused with the formal grandeur of Rome. His works, characterized by their deep color, dramatic lighting, psychological intensity, and often monumental scale, stand as testaments to a singular talent who navigated the crosscurrents of Italian Renaissance art, leaving behind a legacy of compelling and enduring images. He remains a vital figure for understanding the complex artistic exchanges and syntheses that defined this extraordinary era.