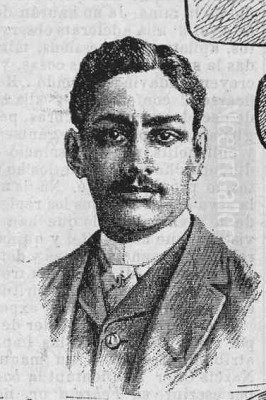

Leopoldo Romañach y Guillén (1862–1951) stands as a monumental figure in the annals of Cuban art. A painter of exceptional skill and a dedicated educator, Romañach's career spanned a transformative period in Cuba's cultural history. His work not only garnered international acclaim but also laid a crucial foundation for subsequent generations of Cuban artists, bridging the gap between 19th-century academic traditions and the burgeoning modernist movements of the 20th century. His life and art offer a compelling narrative of dedication, artistic evolution, and profound influence.

Early Life and European Sojourn

Born in Sierra Morena, Las Villas, Cuba, in 1862, Leopoldo Romañach's artistic inclinations became apparent early on. Like many aspiring artists of his era from Latin America, the pursuit of advanced artistic training often led to Europe, the then-undisputed center of the art world. Romañach was no exception. He embarked on a journey to Italy, choosing Rome as the city to hone his craft. This decision was significant, as Rome, with its rich classical heritage and established art academies, offered a rigorous, traditional arts education.

In Rome, Romañach had the distinct privilege of studying under Filippo Prosperi (also known as Filippo Prospero), a respected Italian painter and professor. Under Prosperi's tutelage, Romañach would have been immersed in the academic style, which emphasized meticulous draftsmanship, a deep understanding of anatomy, classical composition, and the sophisticated use of color and light, often inspired by the Old Masters. This period was crucial in shaping his technical proficiency and providing him with a solid foundation upon which he would later build his unique artistic voice. The experience in Europe exposed him not only to classical and Renaissance art but also to the currents of 19th-century realism and the nascent stirrings of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, which were challenging academic conventions across the continent.

Return to Cuba and a Lifelong Commitment to Education

Upon completing his studies in Europe, Leopoldo Romañach made the pivotal decision to return to his homeland, Cuba. This return marked the beginning of an incredibly influential chapter in his life, not just as a practicing artist but, perhaps more significantly, as an educator. He was appointed as a professor at the prestigious Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes San Alejandro in Havana, often referred to simply as San Alejandro. This institution was, and remains, Cuba's foremost art academy, a crucible for artistic talent.

Romañach's tenure at San Alejandro was nothing short of remarkable; he dedicated half a century to teaching there. This long and consistent presence allowed him to shape the artistic development of countless students. He worked alongside other prominent Cuban artists and educators, most notably Armando Menocal (Armando García Menocal), another key figure in Cuban academic painting who also served as a director of the academy. Together, they were instrumental in maintaining high standards of artistic instruction while also gradually opening doors to newer artistic ideas. Romañach's role as an educator was paramount; he was not merely imparting technical skills but was also fostering a new generation of painters who would go on to define Cuban art in the 20th century.

His commitment to San Alejandro provided a stable and knowledgeable guiding hand for young artists navigating the complexities of art in a rapidly changing world. He was known for his dedication to his students, and his influence extended far beyond the classroom, shaping the very fabric of the Cuban art scene for decades.

Artistic Style: A Fusion of Traditions and Emerging Modernity

Leopoldo Romañach's artistic style is often characterized by its solid academic grounding, infused with a sensitivity to light and atmosphere that sometimes hinted at Impressionistic influences, though he never fully embraced the Impressionist dissolution of form. His primary medium was oil on canvas, and his subject matter was diverse, encompassing portraiture, landscapes, genre scenes, and occasionally, nudes.

His European training under Filippo Prosperi ensured a mastery of traditional techniques. His figures are typically well-drawn and solid, his compositions balanced and thoughtful. However, Romañach was not impervious to the artistic shifts occurring around him. While he remained rooted in a form of realism, his later works, in particular, show a looser brushstroke and a greater interest in capturing the effects of light and color, especially in his depictions of the Cuban landscape and its people. He managed to convey a sense of place and character, often with a subtle emotional depth.

He was a key figure in the transition from purely academic art to what would become known as Cuban modernism, or the "Vanguardia." While not a radical modernist himself in the vein of later artists, Romañach helped to create an environment where new ideas could be explored. He facilitated the acceptance of European modernist tendencies by Cuban artists, acting as a bridge between the old and the new. His work demonstrated that academic skill could coexist with a more contemporary sensibility. Artists like the Spanish master Joaquín Sorolla, known for his luminous beach scenes and vibrant portraits, were achieving international fame during Romañach's active years, and while their styles differed, the broader European interest in light and everyday scenes would have been part of the artistic atmosphere Romañach navigated.

Representative Works: Capturing Essence and Form

Several works stand out in Leopoldo Romañach's extensive oeuvre, showcasing his skill and artistic vision. Among his most recognized paintings is Classic Nude (Desnudo Clásico), created in 1942. This piece, executed later in his career, demonstrates his continued adherence to classical themes and academic rigor, even as modernism was taking firm hold. The painting showcases his mastery of anatomy and the subtle rendering of flesh tones, reflecting the evolution of his style within a classical framework.

Another notable work often cited is Ballerina (La Bailarina). This painting, like many of his portraits and figure studies, would have allowed him to explore the human form, character, and perhaps the interplay of light on fabric and skin. Such pieces highlight his ability to capture not just a likeness but also a sense of presence and personality. His portraits were highly sought after, and he depicted many prominent figures of Cuban society.

Beyond specific titles, his landscapes of the Cuban countryside are also significant. These works often reveal his sensitivity to the tropical light and atmosphere, distinguishing them from purely European academic landscapes. He found ways to interpret the Cuban environment through the lens of his training, contributing to a nascent sense of national identity in art. His genre scenes, depicting everyday life, further underscore his connection to his Cuban heritage and his observational skills. The quality and appeal of his work are reflected in the art market, with pieces like Ballerina commanding respectable valuations at auction, indicative of his enduring legacy.

International Recognition and Exhibitions

Leopoldo Romañach's talent did not go unnoticed beyond Cuba's shores. He achieved significant international recognition during his lifetime, a testament to the quality of his work and its appeal to a broader audience. One of his most notable early successes came at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, commonly known as the St. Louis World's Fair, in 1904. At this major international event, Romañach was awarded a gold medal for his paintings, a significant honor that brought prestige to both the artist and Cuban art in general.

His participation in such international expositions was crucial. These events were major platforms for artists to gain visibility, secure patronage, and engage with artistic developments from around the world. Romañach also reportedly exhibited works and received accolades at the Paris World's Fair (Exposition Universelle), though specific dates and awards from Paris are sometimes cited with less consistency than the St. Louis achievement. Nevertheless, his presence in these international arenas underscored his status as a leading artist of his time.

This international exposure was important not only for Romañach's personal career but also for placing Cuban art on a larger map. It demonstrated that artists from the island were producing work of international caliber, capable of competing with and being appreciated alongside artists from Europe and North America. His successes abroad would have also served as an inspiration for his students and younger Cuban artists.

The San Alejandro Academy: A Crucible of Talent and Romañach's Enduring Influence

The Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes San Alejandro holds a hallowed place in Cuban art history, and Leopoldo Romañach is inextricably linked to its legacy. His half-century of teaching there, alongside his colleague Armando Menocal, was a period of profound impact. They were responsible for training generations of artists, many of whom would go on to become leading figures in the Cuban Vanguardia movement, which truly blossomed in the 1920s and 1930s.

One of Romañach's most famous students was Wifredo Lam. Lam, who would later achieve international superstardom with his unique fusion of Cubism, Surrealism, and Afro-Cuban symbolism, received his foundational art education at San Alejandro during the period when Romañach was a dominant pedagogical force. While Lam's mature style diverged significantly from Romañach's academic realism, the initial training in drawing, composition, and technique provided by teachers like Romañach was an essential starting point.

Other artists who passed through San Alejandro during or shortly after Romañach's influential period, and who became central to the Vanguardia, include Victor Manuel García, Amelia Peláez, Carlos Enríquez, Fidelio Ponce de León, and Domingo Ravenet. While Romañach himself might not have directly taught all of them in their most formative years, his long tenure and the academic standards he upheld created the bedrock upon which these artists built their more experimental practices. He represented a link to tradition, and the Vanguardia, in many ways, reacted against or reinterpreted this tradition. His influence, therefore, can be seen both directly in his students and indirectly in the academic environment he helped to shape, which later artists would either embrace or rebel against to forge their own paths.

The academy under figures like Romañach and Menocal was more than just a school; it was the primary institution for artistic legitimization in Cuba. Graduating from San Alejandro, or teaching there, conferred a certain status. Romañach's role was thus not only as a transmitter of skills but also as a gatekeeper and a standard-bearer for artistic excellence in the country.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Leopoldo Romañach operated within a rich and evolving artistic milieu, both in Cuba and in the broader Latin American and European contexts. In Cuba, his contemporary Armando Menocal was a significant peer, sharing a similar academic background and a long teaching career at San Alejandro. Other Cuban artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries who contributed to the academic tradition include Miguel Melero, an earlier director of San Alejandro, and painters like José Arburu Morell and Esteban Valderrama, who also worked within figurative and landscape traditions.

Internationally, the art world was in tremendous flux during Romañach's career. The Impressionist movement, with artists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, had already revolutionized painting by the time Romañach was establishing himself. Post-Impressionists such as Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin were pushing boundaries further, laying groundwork for Fauvism and Cubism. While Romañach's style remained more conservative, he would have been aware of these seismic shifts. His work can be seen as part of a broader academic-realist tradition that continued to thrive alongside these modernist experiments, particularly in state-sponsored academies and official salons.

His role as an educator also connected him to the future. The artists of the Cuban Vanguardia, such as Amelia Peláez, with her vibrant, stained-glass-inspired cubist forms, or Carlos Enríquez, with his dynamic and often turbulent depictions of Cuban rural life, represented a new direction. Yet, these artists emerged from an environment that Romañach had helped to cultivate. His dedication to fundamental artistic principles provided a point of departure for their innovations.

Later Years, Legacy, and Historical Evaluation

Leopoldo Romañach continued to paint and teach into his later years, remaining an active and respected figure in the Cuban art world until his death in 1951. His long career meant he witnessed enormous changes in art and society. His legacy is multifaceted. As a painter, he produced a significant body of work that captured aspects of Cuban life and landscape with skill and sensitivity. His paintings are held in important collections, including the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Havana, where they are regularly exhibited, ensuring his work remains accessible to new generations.

As an educator, his impact is perhaps even more profound. The sheer number of students who passed through his classes at San Alejandro over five decades means his influence was widely disseminated. He helped to professionalize artistic training in Cuba and maintained a high standard of instruction. While some critical evaluations might note that not all works from such a long career maintained a consistent peak of inspiration—a common observation for prolific artists—his overall historical importance is undisputed.

He is consistently listed among the most important figures in Latin American art history, particularly for his role in the development of Cuban art at a crucial juncture. He represents a vital link between the colonial artistic traditions of the 19th century and the vibrant modernism that characterized Cuban art in the 20th century. His ability to win awards at international expositions like St. Louis also brought Cuban art to a wider stage, fostering a sense of national pride and artistic capability.

Leopoldo Romañach's contribution was not that of a radical innovator in terms of style, but rather that of a master craftsman, a dedicated mentor, and a cultural figure who provided stability and continuity while also being open to the evolving artistic landscape. His work and his teaching helped to define a key era in Cuban art, leaving an indelible mark that continues to be recognized and appreciated.

Conclusion: An Enduring Figure in Cuban Art

Leopoldo Romañach y Guillén was more than just a painter; he was an institution builder and a mentor who shaped the course of Cuban art for over half a century. From his formative studies in Rome under Filippo Prosperi to his long and distinguished professorship at the Academia San Alejandro, Romañach dedicated his life to the pursuit and propagation of artistic excellence. His paintings, characterized by their academic solidity and sensitive portrayal of Cuban subjects, earned him international accolades, including a gold medal at the St. Louis World's Fair.

Through his teaching, he influenced generations of artists, including the seminal Wifredo Lam, and worked alongside esteemed colleagues like Armando Menocal. While firmly rooted in the academic tradition, Romañach's career bridged the 19th and 20th centuries, creating a fertile ground from which the Cuban Vanguardia could emerge. His works, such as Classic Nude and Ballerina, remain important examples of his skill and are treasured in Cuban national collections. Leopoldo Romañach's legacy is that of a foundational figure, a master artist, and a revered educator whose contributions are integral to understanding the rich tapestry of Cuban art history.