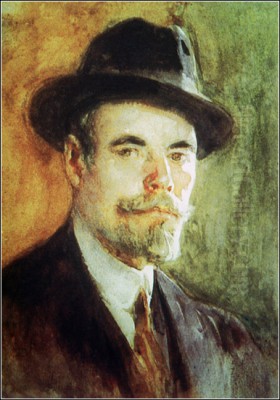

Daniel Hernández Morillo stands as a significant figure in the annals of Peruvian art, a painter whose career bridged the artistic currents of his native land and the cosmopolitan art world of late 19th and early 20th century Paris. Born in Huancavelica, Peru, on August 1, 1856, to a Spanish father and a Peruvian mother, Hernández Morillo's life and work reflect a dedication to the Academic tradition, a profound appreciation for feminine beauty, and a lasting commitment to the development of art in Peru. His journey from the Andean highlands to the Salons of Paris and back to lead Peru's premier art institution is a testament to his talent and determination.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

From a remarkably young age, Daniel Hernández Morillo exhibited an undeniable proclivity for the visual arts. Anecdotal accounts suggest that by the tender age of four, his ability to capture likenesses and express himself through drawing was already apparent, hinting at the prodigious talent that would later define his career. This innate ability was nurtured in Lima, where his family had relocated. The vibrant cultural environment of the Peruvian capital, even in the mid-19th century, provided a backdrop against which his artistic sensibilities began to form.

His formal artistic education commenced in his early teens. At the age of fourteen, a pivotal moment arrived when he began his studies under the tutelage of Leonardo Barbieri, an Italian painter of considerable renown who was active in Lima at the time. Barbieri, recognizing the exceptional promise in his young student, is said to have declared Hernández "born an art master." It was also Barbieri who noted Hernández's early and persistent fascination with depicting the female form, attributing it to an artist's natural draw towards beauty. This early mentorship under a European-trained artist undoubtedly instilled in Hernández a respect for classical techniques and the rigorous discipline of Academic art.

The European Sojourn: Rome and Paris

The allure of Europe, then the undisputed center of the art world, was strong for ambitious artists from the Americas. In 1875, Hernández Morillo's talent earned him a prestigious scholarship from the Peruvian government, enabling him to travel to Europe to further his studies. This was a common path for promising artists from Latin America, seeking to immerse themselves in the traditions and innovations of the Old World. His initial destination was Italy, the cradle of the Renaissance and a repository of classical art.

In Rome, he absorbed the lessons of the Old Masters, studying classical sculpture and Renaissance painting, further refining his draughtsmanship and understanding of composition. It was during this period in Italy that he reportedly had the opportunity to study with the celebrated Spanish painter Marià Fortuny y Marsal. Fortuny, known for his dazzling technique, vibrant genre scenes, and Orientalist subjects, was a major figure in European art, and his influence, particularly his meticulous detail and brilliant brushwork, may have left an impression on the young Peruvian.

Following his formative years in Italy, Hernández Morillo made the crucial decision to move to Paris. The French capital was, by the late 19th century, the epicenter of artistic activity, home to the influential École des Beaux-Arts and the prestigious annual Salons, which were the primary venues for artists to gain recognition and patronage. He would spend a significant portion of his life in Paris, establishing his studio and career there.

Artistic Style and Thematic Focus

Daniel Hernández Morillo remained steadfastly committed to the Academic style throughout his career. This tradition, which emphasized meticulous draughtsmanship, idealized forms, smooth finishes, and often drew upon historical, mythological, or allegorical subjects, was the dominant mode of artistic expression taught in European academies. While Hernández did produce works with historical themes, such as his acclaimed The Death of Socrates (La Muerte de Sócrates), which showcased his mastery of complex multi-figure compositions and dramatic narrative in the grand Academic manner, his most characteristic and celebrated works centered on the depiction of women.

His paintings of women are marked by an air of elegance, grace, and often a subtle, romantic sensuality. He excelled in portraying the textures of luxurious fabrics, the play of light on skin, and the delicate nuances of expression. His subjects were often contemporary women, dressed in the fashionable attire of the Belle Époque, exuding an aura of sophistication and poise. These works were not mere portraits but idealized representations of feminine beauty, capturing a certain societal ideal prevalent at the time. Artists like Alfred Stevens in Belgium and France also gained fame for their elegant portrayals of contemporary women in luxurious interiors, a genre that found widespread appeal.

While firmly rooted in Academicism, some of Hernández's works, particularly later ones like On the Balcony (En el balcón), show a subtle engagement with the fresher palettes and looser brushwork associated with Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. However, he never fully embraced these modernist movements, preferring the refined finish and structured composition of his academic training. His use of color and light, while sometimes bright and atmospheric, generally served to enhance the realism and tactile quality of his subjects rather than to explore the fleeting optical effects that preoccupied the Impressionists like Claude Monet or Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

Success in the Parisian Art World

Living and working in Paris, Hernández Morillo actively participated in the city's vibrant art scene. He regularly submitted his works to the Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, which was the most important platform for artists to achieve recognition. Success at the Salon could make an artist's career, leading to sales, commissions, and critical acclaim. Hernández's polished technique and appealing subject matter found favor with the Salon juries and the public.

His contemporaries in the Parisian Academic scene included towering figures such as Jean-Léon Gérôme, known for his historical and Orientalist paintings, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, celebrated for his idealized nudes and mythological scenes, and Alexandre Cabanel, whose Birth of Venus was a sensation at the Salon of 1863. These artists, along with others like Léon Bonnat, a master portraitist, set the standards for Academic painting, and Hernández Morillo successfully navigated this competitive environment.

His achievements were formally recognized with prestigious awards. In 1900, at the Exposition Universelle in Paris, a major international showcase of arts and industries, he was awarded a gold medal for his artistic contributions. This was a significant honor, placing him among the accomplished international artists of his time. The following year, in 1901, his stature was further cemented when he was named a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour by the French government, a high distinction recognizing outstanding service or achievement.

Return to Peru and Educational Leadership

Despite his success and long residency in Paris, Daniel Hernández Morillo maintained strong ties to his homeland. In the early 20th century, Peru was seeking to modernize and strengthen its cultural institutions. Recognizing the need for a national school of art led by a figure of international standing, the Peruvian government extended an invitation to Hernández Morillo to return and take on a leading role in art education.

He accepted the call, and around 1918-1919 (sources vary slightly on the exact year of his return for this purpose, sometimes citing 1912 or 1917 for the invitation or initial return), he became the first director of the newly established Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes (National School of Fine Arts) in Lima. This institution was pivotal for the development of professional art training in Peru. Under his leadership, the school aimed to provide a rigorous, European-style academic education to a new generation of Peruvian artists.

His directorship marked a significant phase in his career, transitioning from a practicing artist in Paris to a leading arts educator and administrator in his home country. He brought his extensive experience and adherence to Academic principles to the school's curriculum. This period saw the emergence of artists who would go on to shape Peruvian art in diverse ways. While Hernández championed Academicism, the early 20th century was also a time of burgeoning new artistic ideas in Latin America, including the rise of Indigenismo, a movement that sought to valorize indigenous cultures and themes. Artists like José Sabogal, who would later lead the Indigenist movement, represented a different path, but Hernández's role in establishing a formal art education system was foundational. He would have been aware of the work of earlier Peruvian masters like Francisco Laso, who had already begun to explore national themes in the 19th century, and contemporaries like Teófilo Castillo, who was an early proponent of Impressionism in Peru. Another notable Peruvian contemporary who also found fame in Paris was the portraitist Carlos Baca-Flor.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Two paintings are frequently cited as representative of Daniel Hernández Morillo's oeuvre: The Death of Socrates and On the Balcony.

The Death of Socrates is a quintessential example of a grand historical painting in the Academic tradition. Depicting the final moments of the ancient Greek philosopher, condemned to die by drinking hemlock, the work showcases Hernández's skill in composing a complex scene with multiple figures, conveying dramatic tension, and rendering anatomical detail with precision. Such paintings were highly valued in Academic circles for their moral and intellectual content, as well as their technical virtuosity. The subject itself, a stoic philosopher facing death for his principles, was a popular one, treated by other artists such as the French Neoclassical painter Jacques-Louis David.

On the Balcony (En el balcón), on the other hand, represents the more intimate and charming side of his work. This painting typically features one or more elegantly dressed women on a balcony, often adorned with flowers, gazing outwards or engaged in quiet contemplation. These scenes allowed Hernández to explore the play of light, the textures of fabric, and the creation of a romantic, slightly wistful mood. While still fundamentally Academic in its careful rendering, works like this sometimes hint at a lighter palette and a more relaxed atmosphere, possibly reflecting a subtle awareness of Impressionistic trends, much like some works by the Spanish master Joaquín Sorolla, who masterfully blended academic skill with impressionistic light.

Other works by Hernández often feature solitary female figures in opulent interiors, reading, playing musical instruments, or simply posing, always exuding an air of refined femininity. These paintings catered to the tastes of the bourgeois collectors of the era, who appreciated the technical skill and the pleasing, non-controversial subject matter.

Critical Reception and Historical Context

During his lifetime, particularly during his Parisian period, Daniel Hernández Morillo enjoyed considerable success and positive critical reception within the established art world. His awards and regular acceptance into the Salons attest to his standing. His work aligned well with the prevailing tastes of the Academic establishment and the art-buying public.

However, art history is a field of evolving perspectives. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Academic tradition was increasingly being challenged by avant-garde movements, from Impressionism and Post-Impressionism (think Vincent van Gogh or Paul Cézanne) to Fauvism and Cubism. Artists associated with these movements often criticized Academic art as formulaic, overly sentimental, and out of touch with modern life.

In more recent times, some art historians and critics have viewed Hernández Morillo's focus on idealized female beauty through a contemporary lens, occasionally suggesting that his work catered to a male gaze or lacked deeper social or intellectual engagement beyond the aesthetic. This critique is not unique to Hernández but is often applied to many Academic painters of the era who specialized in similar themes. For instance, the works of Bouguereau or Cabanel, while technically brilliant, have faced similar re-evaluations.

It is important, however, to understand Hernández's work within its historical context. The celebration of idealized beauty was a central tenet of Academic art, and his depictions of women were in line with the aesthetic sensibilities of his time. Furthermore, his contribution to establishing a national art school in Peru was of undeniable importance for the country's artistic development, providing a formal institutional framework for art education that would influence generations. His contemporary in Spain, Ignacio Zuloaga, also focused on traditional themes and figures, albeit with a distinctly Spanish character, and similarly navigated the space between tradition and emerging modernism.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Daniel Hernández Morillo dedicated his later years to his role as director of the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes in Lima, shaping its curriculum and mentoring young artists. He passed away in Lima on October 23, 1932, leaving behind a significant body of work and a lasting institutional legacy.

His paintings are held in various collections, including the Museo de Arte de Lima and other public and private collections in Peru and abroad. He is remembered as one of Peru's foremost Academic painters, a master technician who achieved international recognition and played a crucial role in the professionalization of art education in his homeland. While artistic tastes have shifted over the decades, there has been a renewed appreciation for the skill and artistry of Academic painters, and Hernández Morillo's work continues to be studied and admired for its elegance, refinement, and technical mastery.

His life story, from the highlands of Peru to the art academies of Europe and the Salons of Paris, and finally back to a position of leadership in Peruvian art, reflects a dedication to his craft and a significant contribution to the cultural heritage of his nation. He successfully bridged two worlds, absorbing European artistic traditions and then applying that knowledge to foster artistic development in Peru, ensuring his place as a key figure in Latin American art history.