Philip Richard Morris ARA (4 December 1836 – 22 April 1902) was a distinguished English painter of the Victorian era, known for his evocative historical, biblical, and genre scenes, and later in his career, for his portraiture. He navigated the bustling and diverse art world of nineteenth-century Britain, achieving recognition from prestigious institutions like the Royal Academy of Arts. While perhaps not as universally renowned today as some of his contemporaries, Morris carved out a significant career, contributing to the rich tapestry of Victorian art with works that resonated with the sensibilities and narratives of his time. His journey from a childhood in Devonport to the esteemed halls of the Royal Academy and a long, productive career reflects both personal dedication and the artistic currents of his age.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Devonport, Devon, on December 4, 1836, Philip Richard Morris grew up in an environment that was perhaps not immediately indicative of an artistic career. His father, John Simmons Morris, was an iron founder and engineer, a profession grounded in the practical and industrial advancements of the era. This background in engineering and industry, while different from the fine arts, may have instilled in the young Morris a sense of craftsmanship and precision. It's not uncommon for artists to emerge from families with diverse professional backgrounds, sometimes in reaction to, or inspired by, the skills and environments they were exposed to in their formative years.

The specific catalysts for Morris's turn towards art are not extensively documented, but like many aspiring artists of his generation, he would have been aware of the burgeoning art scene in Britain. The mid-nineteenth century was a period of great artistic ferment, with the Royal Academy holding a central, if sometimes contested, position, and new movements like the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood challenging established norms. For a young man with artistic inclinations, London, with its academies, galleries, and museums, would have been the ultimate destination. His early education likely provided a foundation, but the specialized training required for a professional artist necessitated a move towards more formal instruction.

Before fully committing to the Royal Academy Schools, Morris is noted to have spent time studying the Elgin Marbles at the British Museum. This was a common and highly recommended practice for art students. The Elgin Marbles, sculptures from the Parthenon in Athens, were considered paragons of classical art, offering invaluable lessons in anatomy, form, and composition. Studying these ancient masterpieces provided a direct link to the classical tradition that underpinned much of Western academic art. Artists like Benjamin Robert Haydon had passionately advocated for their importance, and generations of British artists, including Lord Frederic Leighton and Edward Poynter, drew inspiration from such classical sources. This period of self-directed study would have honed Morris's observational skills and deepened his understanding of the human form, preparing him for the more structured environment of the Academy.

Formal Training and Early Successes at the Royal Academy

In 1855, at the age of approximately nineteen, Philip Richard Morris took the pivotal step of enrolling in the Royal Academy Schools in London. This institution was the preeminent training ground for artists in Britain, offering a rigorous curriculum focused on drawing from the antique, life drawing, and the study of Old Masters. Admission was competitive, and the training was designed to equip students with the technical skills necessary to succeed in various genres, from historical painting to portraiture.

During his time at the Royal Academy Schools, Morris proved to be a talented and diligent student. He garnered several accolades, including two silver medals, which were awarded for excellence in specific areas of study, such as drawing or painting from life. These early recognitions would have been encouraging, signaling his potential within the competitive academic environment. His teachers would have included prominent Academicians of the day, though specific names are not always recorded in general biographies. The influence of figures like Charles West Cope, who taught painting, or Daniel Maclise, known for his historical frescoes, might have been felt within the Academy's studios.

The culmination of his student career came in 1858 when, at the age of twenty-two, Morris won the coveted Gold Medal for his historical painting, "The Good Samaritan." This was a significant achievement, marking him as one of the most promising students of his cohort. The Gold Medal was not just an award; it was a prestigious honor that often launched the careers of young artists. The subject itself, "The Good Samaritan," was typical of the kind of morally uplifting and narratively rich themes favored by the Academy. It allowed the artist to demonstrate skills in composition, anatomical rendering, emotional expression, and the depiction of historical or biblical costume and setting. This success was a testament to his mastery of the academic principles he had absorbed during his training.

Furthermore, Morris was awarded the Prize of Rome, more formally known as the Travelling Studentship. This prize provided funds for the recipient to travel and study abroad, typically in Italy, for a period of three years. This was an invaluable opportunity for an artist to experience firsthand the great masterpieces of the Renaissance and antiquity in Rome, Florence, Venice, and other cultural centers. Such a journey would have exposed Morris to the works of Raphael, Michelangelo, Titian, and countless other masters, broadening his artistic horizons and refining his taste. This experience was considered crucial for aspiring historical painters, allowing them to absorb the grandeur and technical brilliance of the Italian schools.

Launching a Career: Themes and Early Works

Following his successes at the Royal Academy Schools and his enriching travels, Philip Richard Morris began to establish himself as a professional artist. He started exhibiting regularly at the Royal Academy's annual exhibitions, a crucial venue for artists to showcase their work, attract patrons, and gain critical attention. His first exhibit at the Royal Academy was in 1858, the same year he won the Gold Medal, likely with "The Good Samaritan" itself. He would continue to exhibit there almost annually until 1901, a remarkable span of over four decades.

In his early career, Morris primarily focused on historical and biblical subjects, genres that were highly esteemed within the academic hierarchy. These themes allowed for grand compositions, dramatic narratives, and the depiction of noble human actions and emotions. His religious illustrations, such as those depicting scenes from the life of Moses, would have aligned with the Victorian era's strong interest in biblical narratives, both for their spiritual content and their dramatic potential. Works in this vein required considerable research into historical costume, architecture, and customs, as well as a strong command of figure composition and expression.

Beyond purely historical or biblical scenes, Morris also ventured into genre painting, often with a sentimental or narrative leaning. Titles like "Sailor's Wedding" and "Première Communion" (First Communion) suggest an interest in capturing poignant moments from contemporary or near-contemporary life. "Sailor's Wedding" likely depicted the emotional farewells or joyful reunions associated with maritime life, a popular theme in British art given the nation's seafaring identity. William Powell Frith had achieved immense success with his panoramic depictions of modern life, and while Morris's genre scenes may have been more intimate, they shared an interest in storytelling and human emotion. "Première Communion" would have appealed to the religious sentiments of the era, focusing on a significant rite of passage and allowing for tender portrayals of youth and piety.

The provided information also mentions a particular skill in embroidery, with a representative work titled "After." If this refers to the same Philip Richard Morris, it suggests a versatility beyond painting, perhaps aligning with the broader Arts and Crafts ethos championed by figures like William Morris (no direct relation, but a prominent contemporary). However, Philip Richard Morris's primary public identity and his recognition by the Royal Academy were firmly rooted in his work as a painter. It's possible this was a private pursuit or a less emphasized aspect of his output. Another embroidery piece mentioned is "The Reaper," which, like "After," would suggest an interest in allegorical or pastoral themes if indeed by his hand.

Artistic Style and Development

Philip Richard Morris's artistic style, particularly in his historical and genre paintings, would have been shaped by his academic training and the prevailing tastes of the Victorian era. His work likely demonstrated strong draughtsmanship, a balanced sense of composition, and careful attention to detail, all hallmarks of an artist schooled in the traditions of the Royal Academy. The narrative clarity of his paintings would have been paramount, as Victorian audiences appreciated art that told a story or conveyed a moral message.

His color palette would likely have been rich and varied, capable of conveying both the solemnity of biblical scenes and the more vibrant atmosphere of genre subjects. The influence of his Italian travels might have been visible in his handling of light and shadow, and perhaps in a certain classical grace in his figures, though this would have been tempered by the more naturalistic tendencies of British art.

While not an avant-garde artist in the vein of the Impressionists who were beginning to emerge in France during his career, Morris would have been aware of the artistic developments around him. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, with artists like John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and William Holman Hunt, had already made a significant impact with their emphasis on truth to nature, bright colors, and detailed finish, even if their initial rebellion had softened by the time Morris was establishing himself. Their influence was pervasive, encouraging a general trend towards greater naturalism and detail in British painting.

Morris's style can be situated within the broader context of Victorian narrative painting. He shared with contemporaries like Abraham Solomon or Frank Holl an interest in depicting scenes that evoked empathy or told a compelling story. His historical paintings would have aimed for a degree of archaeological accuracy, a concern shared by academic painters like Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, who was renowned for his meticulous reconstructions of the ancient world.

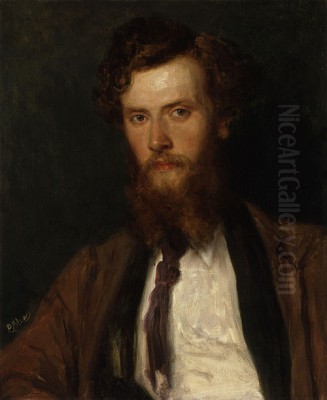

As his career progressed, Morris increasingly turned to portraiture. This was a common trajectory for many successful artists. Portrait commissions offered a steady source of income and were highly valued by patrons seeking to commemorate themselves and their families. His academic training would have provided a strong foundation for portrait painting, enabling him to capture a likeness while also imbuing his subjects with a sense of dignity and character. His portrait style likely combined a faithful representation of the sitter with an attention to the textures of fabric and the subtleties of expression, in line with the expectations for society portraiture of the late Victorian period. Artists like George Frederic Watts and Hubert von Herkomer were prominent portraitists of this era, setting high standards in the field.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Professional Life

Philip Richard Morris's long and consistent record of exhibiting at the Royal Academy from 1858 to 1901 underscores his sustained professional activity and his acceptance within the mainstream art establishment. The Royal Academy's Summer Exhibition was the most important annual art event in London, attracting vast crowds and significant press coverage. To have one's work accepted and well-hung was crucial for an artist's reputation and commercial success.

In 1877, Morris received a significant professional honor when he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA). This was an important step towards becoming a full Royal Academician (RA). Associates had certain privileges and were recognized as artists of significant standing. This election acknowledged his consistent contributions and the quality of his work over nearly two decades of exhibiting. While he did not, it seems, proceed to become a full RA, the ARA distinction itself was a mark of considerable achievement in the competitive London art world.

Beyond the Royal Academy, Victorian artists often exhibited at other venues, such as the British Institution, the Society of British Artists, or in regional exhibitions in cities like Liverpool, Manchester, and Birmingham. While specific records of Morris's participation in these other venues are not detailed in the provided information, it is likely he sought opportunities to show his work more widely.

His professional life would have involved not only the creation of art but also the business of art: dealing with patrons, managing commissions, and navigating the social and professional networks of the art world. London in the latter half of the nineteenth century was a vibrant hub for artists, with numerous studios, art clubs, and societies fostering a sense of community and, at times, rivalry.

Personal Life

Details about Philip Richard Morris's personal life are somewhat sparse in readily available records, as is often the case for artists who were not figures of major public scandal or celebrity. The provided information indicates he was the son of J.S. Morris, an engineer and ironfounder. This connection to industry is an interesting counterpoint to his artistic pursuits.

A significant personal detail mentioned is his marriage in Llangollen, a picturesque town in Denbighshire, Wales. His wife was Ann Williams. The context provided about Ann Williams's previous marriage to an Edward and subsequent remarriage to a Richard Morris after Edward's death is somewhat confusing and might pertain to a different Richard Morris, or there could be a conflation of details. However, the core information suggests Philip Richard Morris did marry, and Llangollen was the location of this event. Marriage and family life often played a role in the stability and subject matter of Victorian artists, though specific influences on Morris's work from his personal life are not explicitly detailed.

The life of a Victorian artist, even a successful one, involved dedication and hard work. Studio practice, sourcing models, preparing canvases, and the often lengthy process of creating large historical or narrative paintings demanded considerable time and energy. Portrait commissions, while lucrative, also required sittings and careful negotiation with clients.

Later Career, Legacy, and Historical Assessment

In the later part of his career, Philip Richard Morris increasingly focused on portraiture. This shift was common for established artists. While historical and biblical paintings brought prestige and academic recognition, portraits often provided more consistent and lucrative commissions. The demand for portraits was high among the affluent middle and upper classes of Victorian society, who wished to have their likenesses preserved. Morris's skill in capturing character and his academic training would have served him well in this genre. He continued to exhibit at the Royal Academy until 1901, just a year before his death.

Philip Richard Morris passed away on April 22, 1902, at the age of 65. He left behind a substantial body of work, created over more than four decades of professional practice. His art, rooted in the academic traditions of the Royal Academy, reflected many of the prevailing tastes and values of the Victorian era: a love for narrative, an appreciation for technical skill, and an interest in subjects that were by turns morally edifying, historically evocative, or sentimentally engaging.

In the broader sweep of art history, Philip Richard Morris is perhaps not as widely known today as some of his more revolutionary or flamboyant contemporaries. The early 20th century saw a dramatic shift in artistic tastes, with the rise of modernism leading to a re-evaluation of Victorian art. For a time, many Victorian academic painters fell out of favor, their work sometimes dismissed as overly sentimental or academic in a pejorative sense. However, in more recent decades, there has been a renewed scholarly and public interest in Victorian art, with a greater appreciation for its diversity, technical accomplishment, and its insights into the culture of the period.

Artists like Philip Richard Morris played an important role within their contemporary art world. They contributed to major exhibitions, fulfilled significant commissions, and helped to shape the visual culture of their time. His Gold Medal for "The Good Samaritan" and his election as an ARA attest to the esteem in which he was held by his peers. His paintings would have been seen and discussed by thousands of exhibition-goers, contributing to the public discourse on art and storytelling.

While specific works like "The Good Samaritan," "Sailor's Wedding," and "Première Communion" are noted, a fuller appreciation of his oeuvre would require a more comprehensive catalogue of his exhibited works and surviving paintings, many of which are likely in private collections or regional museums. His religious illustrations, such as those of Moses, also form part of his contribution, reflecting the Victorian era's deep engagement with biblical texts.

Conclusion

Philip Richard Morris ARA stands as a representative figure of the dedicated and skilled professional artist within the Victorian academic tradition. From his early studies of the Elgin Marbles to his successes at the Royal Academy Schools, including the Gold Medal and Travelling Studentship, he followed a path recognized for its rigor and prestige. His career, spanning over forty years of consistent exhibition at the Royal Academy, demonstrates a sustained commitment to his art.

He adeptly navigated the popular genres of his time, producing historical and biblical narratives that appealed to Victorian sensibilities, engaging genre scenes that captured moments of human emotion, and, later, portraits that served the commemorative needs of his patrons. While the artistic landscape shifted dramatically towards the end of his life and in the decades following his death, Morris's contributions remain part of the rich and complex story of nineteenth-century British art. His work offers a window into the artistic values, narrative preoccupations, and technical standards of a significant period in art history, deserving of recognition for its craftsmanship and its earnest engagement with the themes that moved his contemporary audience. His legacy is that of a talented and respected painter who successfully carved out a career within the demanding art world of Victorian Britain.