Lillian Mathilde Genth (1876-1953) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of American Impressionism. Renowned primarily for her idyllic depictions of female nudes gracefully integrated into sun-dappled natural settings, Genth carved a unique niche for herself in an art world largely dominated by male artists. Her journey from a scholarship student in Philadelphia to a recognized name in American art, her stylistic evolution, and her eventual, somewhat enigmatic, departure from her most famous subject matter offer a fascinating study of an artist navigating her times. This exploration will delve into her life, her artistic development, the influences that shaped her, her key works, and her enduring place in art history.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Philadelphia

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on July 3, 1876, Lillian Genth's artistic inclinations emerged early. Philadelphia, at the turn of the century, was a vibrant center for arts and culture, boasting institutions like the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), one of the oldest and most prestigious art schools in the United States. It was in this environment that Genth's formal artistic training began. She secured a scholarship to attend the Philadelphia School of Design for Women (now Moore College of Art & Design), a crucial institution that provided professional art education for women at a time when such opportunities were not universally available.

During her studies at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women, Genth came under the tutelage of Elliot Daingerfield (1859-1932). Daingerfield, an artist known for his Tonalist landscapes and later, more Symbolist works, exerted a considerable influence on the young Genth. His emphasis on mood, atmospheric effects, and a harmonious, often subdued, color palette would resonate in Genth's early work and continue to inform her understanding of light and color throughout her career. Daingerfield's guidance likely helped Genth develop the sensitivity to tonal values and the poetic quality that would later characterize her celebrated nudes in nature.

European Sojourn: Whistler's Influence and Parisian Studies

The ambition of many American artists of that era was to study in Europe, particularly in Paris, then the undisputed capital of the art world. In 1900, Lillian Genth's talent was recognized with a fellowship that funded a year of study abroad. This opportunity was transformative. She traveled to Paris and enrolled at the Académie Carmen, a school founded by the expatriate American artist James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903). Whistler, a towering figure known for his aesthetic philosophy of "art for art's sake," his Tonalist paintings, and his flamboyant personality, had a profound impact on Genth.

Whistler's emphasis on subtle harmonies, refined color palettes, and the overall decorative arrangement of a composition deeply influenced Genth's developing style. His teachings, which often focused on capturing the essence and mood of a subject rather than literal representation, would have complemented the earlier lessons from Daingerfield. The experience of working under Whistler, even if his school was relatively short-lived, provided Genth with a direct link to one of the most innovative artistic minds of the late 19th century. This period in Paris exposed her to the currents of European modernism, including the lingering influence of French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, which undoubtedly broadened her artistic horizons.

Return to America: Recognition and the Emergence of a Signature Style

Upon her return to the United States, Lillian Genth began to establish her professional career. She held her first solo exhibition at the prestigious Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, a significant milestone for any emerging artist. Her talent did not go unnoticed. In 1904, PAFA awarded her the Mary Smith Prize, an annual award given to the most outstanding work by a woman artist residing in Philadelphia. This accolade was a considerable honor and helped to solidify her reputation.

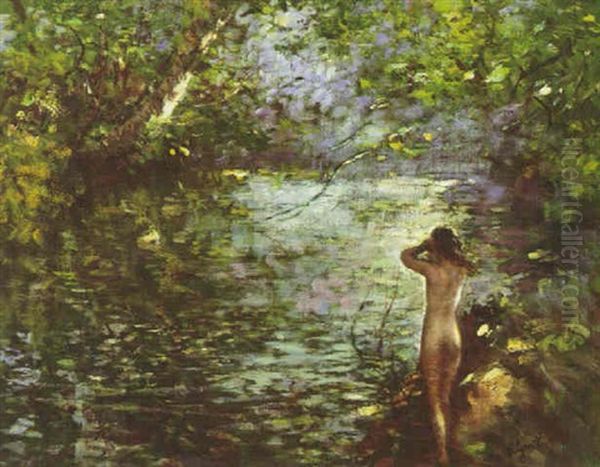

Around 1906, Genth began to explore the theme that would define much of her career: the female nude in a landscape setting. This was a bold choice for a female artist in early 20th-century America. While the nude had a long tradition in Western art, its depiction by women artists, particularly in the more conservative American context, was less common and could court controversy. Genth, however, approached the subject with a sensitivity and lyricism that found favor. Her nudes were not presented as academic studies or mythological figures in the classical sense, but rather as ethereal beings harmoniously integrated into sunlit, often secluded, natural environments – woodlands, by streams, or in clearings. This fusion of the human form with the Impressionistic rendering of light and nature became her hallmark.

Her style during this period clearly showed the influence of Impressionism, characterized by broken brushwork, a vibrant palette, and a keen interest in capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere. Unlike some of her American Impressionist contemporaries like Childe Hassam (1859-1935) or Willard Metcalf (1858-1925), who often focused on urban scenes or New England landscapes, Genth's primary focus became these idyllic, almost Arcadian, scenes. Her work shared a certain romantic sensibility with artists like Frederick Carl Frieseke (1874-1939), another American Impressionist who often depicted women in sun-dappled gardens, though Genth's consistent focus on the nude set her apart.

The Nude in the Landscape: A Lyrical Vision

Lillian Genth’s depictions of nudes in landscapes were celebrated for their beauty, serenity, and masterful handling of light. Her figures often appear unselfconscious, at ease in their natural surroundings, embodying a sense of freedom and connection with the earth. The settings themselves were rendered with an Impressionist's eye for color and light, with dappled sunlight filtering through leaves, reflecting off water, and caressing the skin of her subjects. This created a shimmering, vibrant surface that unified figure and ground.

Works like "Siren of the Glen" exemplify this period. The title itself evokes a mythical, enchanting quality. While specific details of this painting might vary in interpretation, one can imagine a scene where the female form is subtly revealed amidst lush foliage, the play of light creating an almost mystical atmosphere. Her nudes were often solitary figures, enhancing the sense of intimacy and private communion with nature. She managed to imbue these scenes with a sense of timelessness, avoiding overt narrative or contemporary references.

The success of these paintings was considerable. Genth gained widespread recognition and her works were sought after by collectors and exhibited in prominent galleries. She was elected an Associate of the National Academy of Design in 1908, a significant professional acknowledgment. Her ability to successfully and tastefully combine the nude form with natural landscapes resonated with an audience that appreciated both the aesthetic beauty of the human body and the allure of Impressionist landscape painting. Her approach can be seen as a continuation of the Arcadian tradition in art, which idealizes rural life and harmony with nature, but filtered through a distinctly modern, Impressionistic lens. She joined a lineage of artists who explored the nude in nature, from European masters like Titian and Giorgione to more contemporary figures like Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), though Genth’s vision was uniquely her own.

Artistic Evolution and Later Career: A Shift in Focus

For over two decades, Lillian Genth was primarily known for her sunlit nudes. However, in 1928, she made a surprising announcement: she would no longer paint nudes. The reasons for this decision are not entirely clear and have been subject to some speculation. Perhaps she felt she had fully explored the subject, or maybe she sought new artistic challenges. It could also have been a response to changing artistic tastes as modernism continued to evolve beyond Impressionism, with movements like Art Deco and Surrealism gaining traction.

Following this decision, Genth turned her attention to different subjects, notably Spanish and "Oriental" themes. This shift was not uncommon among artists of the period; figures like John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) and William Merritt Chase (1849-1916) also explored diverse subjects and international locales throughout their careers. Genth traveled, and her new works reflected these experiences, capturing the landscapes, people, and cultural artifacts of these regions. While these later works may not have achieved the same level of fame as her nudes, they demonstrate her versatility and continued artistic exploration. She also continued to paint other subjects, including still lifes, as evidenced by works like "Apple Blossoms and Daffodils," showcasing her skill in composition and color beyond figurative work.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Collections

Throughout her career, Lillian Genth exhibited her work widely and received numerous accolades. Beyond her early success with the Mary Smith Prize and her election to the National Academy of Design, her paintings were shown at important venues. For instance, she had an exhibition of "Recent Paintings by Lillian Genth" at the Milch Galleries in New York from March 17 to 29, 1919. Milch Galleries was a significant dealer for many American artists of the period.

Her works found their way into important public and private collections. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York holds a work by Genth, reportedly a donated piece, indicating her recognition by major institutions. Her paintings are also part of the collection at the Frye Art Museum in Seattle, which focuses on late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century European and American representational art. More recently, her contributions have been highlighted in thematic exhibitions, such as "Rebel Women: American Impressionist Women from the Sellars Collection," which traced the role of female artists within the American Impressionist movement. Such exhibitions help to re-evaluate and bring renewed attention to artists like Genth, placing their work within a broader art historical and social context, alongside other pioneering women Impressionists such as Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), Lilla Cabot Perry (1848-1933), and Cecilia Beaux (1855-1942), though Beaux was more known for her portraiture.

Her work was also noted in publications of her time. For example, "Forgotten Books" (likely a modern reprint series of older texts) mentions her distinctive style in landscape and nude painting, underscoring her contemporary reputation.

Personal Life: Glimpses Beyond the Canvas

While much of the focus on Lillian Genth is on her artistic output, some details about her personal life offer a more rounded picture of the woman behind the art. The provided information suggests a multifaceted personality. It mentions her marriage to George L. Reinhold. It also intriguingly notes multi-lingual abilities, suggesting she could incorporate Hebrew, Sudanese, and Arabic into her persona, hinting at a broad intellectual curiosity or perhaps familial connections that are not widely documented in standard art historical accounts. A deep love for the American South is also mentioned as an influential part of her life.

The provided information also alludes to more complex aspects of her later life, mentioning two instances of dismissal for misconduct: one for allegedly mailing a prisoner's letters to a girlfriend, and another for drinking surplus milkshakes from a charity event. These anecdotes, if accurate, paint a picture of a non-conformist individual, perhaps even a somewhat eccentric character in her later years. It's important to approach such personal details with care, as they can sometimes be apocryphal or taken out of context. However, the source also emphasizes her deep love for family members and a definition of "privilege" that transcended societal norms of race or class, suggesting a person of strong, perhaps unconventional, convictions. She reportedly resided for a time in Manhattan's Belnord Apartments, a grand apartment building that housed many notable residents.

These glimpses, though fragmented, suggest a life lived with a certain independence and perhaps a disregard for conventional expectations, which might also be reflected in her bold choice of subject matter as an artist.

Legacy and Art Historical Position

Lillian Genth's primary legacy lies in her distinctive contribution to American Impressionism, particularly her specialization in the female nude integrated into sun-drenched landscapes. She successfully navigated a field where women artists often faced greater obstacles than their male counterparts, achieving significant recognition and commercial success during her lifetime. Her work stands as a testament to her skill in capturing the effects of light and atmosphere, her sensitive portrayal of the female form, and her ability to create idyllic, harmonious compositions.

While the popularity of Impressionism waned with the rise of later modernist movements, there has been a renewed appreciation for American Impressionists, including a greater focus on the contributions of women artists within the movement. Genth's work is an important part of this narrative. She, along with artists like Pauline Palmer (1867-1938) and Helen Maria Turner (1858-1958), expanded the scope of Impressionism in America, bringing unique perspectives and subject matter.

Her decision to cease painting nudes in 1928 marks a significant turning point in her career, and while her later works exploring Spanish and Oriental themes are part of her oeuvre, it is her luminous nudes that remain her most celebrated and recognizable achievement. These paintings continue to be admired for their beauty, their technical skill, and their embodiment of a serene, almost timeless vision of harmony between humanity and nature. Artists like Robert Reid (1862-1929), another of "The Ten" American Painters, also explored decorative figures in landscapes, but Genth's consistent focus and particular style of integrating the nude made her work stand out.

Comparisons and Contemporaries: Genth in Context

To fully appreciate Lillian Genth's contributions, it's useful to consider her within the context of her contemporaries. In America, the Impressionist movement included prominent figures like John Henry Twachtman (1853-1902), J. Alden Weir (1852-1919), and Frank Weston Benson (1862-1951), many of whom were part of "The Ten American Painters." While Genth was not part of this specific group, her work shares the Impressionist concern for light, color, and often, idyllic subject matter.

Her focus on the female figure in outdoor settings can be compared to Frederick Carl Frieseke, as mentioned, but also to Richard E. Miller (1875-1943), who often painted women in interiors or gardens with a similar decorative and light-filled quality. However, Genth’s consistent and prominent use of the nude, rather than clothed figures, distinguishes her.

Internationally, the legacy of French Impressionists like Claude Monet (1840-1926) for landscape and light, and Edgar Degas (1834-1917) or Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) for figurative work, provided a backdrop for all Impressionist painters. Morisot, as a leading female Impressionist in France, offers an interesting point of comparison in terms of navigating the art world as a woman, though her subject matter was generally focused on domestic scenes and portraits.

Genth’s early mentor, Elliot Daingerfield, represented the Tonalist sensibility, which also influenced other American artists like George Inness (1825-1894). Her Parisian mentor, James McNeill Whistler, was a pivotal figure bridging American and European art, whose aestheticism impacted a generation. Genth successfully synthesized these influences into a style that was distinctly her own.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Light and Form

Lillian Genth's career spanned a dynamic period in American art. She absorbed the lessons of Tonalism and the aestheticism of Whistler, embraced the vibrancy of Impressionism, and created a body of work that celebrated the beauty of the female form in harmony with nature. Her sunlit nudes are her most enduring legacy, paintings that evoke a sense of peace, freedom, and timeless beauty. While her later shift in subject matter indicates an artist willing to explore new avenues, it is these earlier works that solidified her place in American art history.

As a successful woman artist in the early 20th century, she broke ground and achieved significant recognition. Her paintings continue to be appreciated in collections and exhibitions, reminding us of her unique vision and her skillful ability to capture the ephemeral qualities of light and the graceful elegance of the human form within the embrace of the natural world. Lillian Genth remains an important figure for those studying American Impressionism, women in art, and the enduring allure of the pastoral nude. Her work invites viewers into a world of serene beauty, a testament to her artistic talent and her distinctive contribution to the art of her time. She passed away in 1953, leaving behind a legacy of luminous and evocative art.