Hermann Dudley Murphy stands as a significant figure in American art history, particularly noted for his contributions during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. An accomplished painter, influential teacher, and pioneering frame designer, Murphy navigated the evolving artistic landscapes of Boston and Paris, leaving behind a legacy characterized by subtle beauty, technical skill, and a holistic approach to art presentation. His work embodies the transition from academic traditions to the more atmospheric and subjective styles of Tonalism and Impressionism, while his innovations in frame making underscored the burgeoning Arts and Crafts ideals in America.

Early Life and Formative Education

Hermann Dudley Murphy was born in Marlborough, Massachusetts, in 1867. His heritage reflected the American melting pot; his father was an immigrant from Ireland, while his mother hailed from a long-established New Hampshire family. This background perhaps contributed to the blend of European sensibility and American practicality that would later define his career. His early education took place at the Chauncy Hall School in Boston, a preparatory school known for its rigorous academics.

Murphy's formal art training commenced in 1886 when he enrolled at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. This institution was a crucible for artistic talent in New England. During his time there, he studied under notable instructors such as Otto Grundmann, a German-born painter who brought European academic methods to the school, and Joseph Rodefer DeCamp, a prominent American Impressionist and figure painter associated with the Boston School. These early teachers provided Murphy with a solid foundation in drawing, painting, and composition.

Seeking broader horizons and deeper immersion in contemporary art movements, Murphy traveled to Paris in 1891. He remained in the French capital until 1896, studying at the prestigious Académie Julian. This academy was a popular destination for international students, known for its less rigid structure compared to the official École des Beaux-Arts and for teachers like William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant. The Parisian environment exposed Murphy to a vibrant art scene, pulsating with the influences of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and Symbolism.

The Influence of Whistler and the Rise of Tonalism

During his formative years, particularly his time in Paris, Murphy fell under the powerful influence of James McNeill Whistler. Whistler, an American expatriate artist based primarily in London and Paris, was a leading proponent of the Aesthetic Movement and the concept of "art for art's sake." His emphasis on tonal harmony, subtle color palettes, simplified compositions, and the overall atmospheric mood of a painting resonated deeply with Murphy.

This influence steered Murphy towards Tonalism, an American artistic style that emerged in the 1880s and flourished into the early twentieth century. Tonalism, practiced by artists like George Inness and Dwight Tryon, favored muted colors, soft edges, and evocative, often melancholic, atmospheres. Murphy adopted this approach, developing a distinctive style characterized by its preference for soft, harmonious color schemes and unified compositions, often depicting scenes at twilight or in hazy conditions to enhance the poetic mood. Whistler's impact extended beyond painting technique; it also shaped Murphy's understanding of art presentation, including the crucial role of the frame.

While Tonalism formed the bedrock of his style, Murphy also absorbed lessons from Impressionism, particularly in his handling of light and color, though generally applied with more restraint than seen in French Impressionists like Claude Monet. He skillfully blended the atmospheric qualities of Tonalism with the brighter palette and observational focus associated with Impressionism, creating works that were both evocative and grounded in visual reality.

Painting Style: Subjects and Characteristics

Murphy's oeuvre encompasses a range of subjects, including portraits, landscapes, and still lifes. He demonstrated proficiency in each genre, adapting his Tonalist and Impressionist sensibilities accordingly. His portraits often possess a quiet dignity and psychological depth, rendered with subtle modeling and harmonious color. His landscapes capture the specific moods of nature, whether the tranquil harbors of New England or the sun-drenched vistas encountered during his travels.

He gained particular renown for his still life paintings, especially those featuring flowers. These works often combine the delicate rendering of floral arrangements with carefully chosen decorative objects in the background. Murphy frequently included exquisite Chinese ceramics, bronze figures, and other objets d'art, reflecting the Aesthetic Movement's appreciation for Oriental aesthetics and beautiful craftsmanship. These still lifes are notable for their sophisticated compositions, often employing classical formats, balanced arrangements, and a masterful interplay of light, color, and texture. The backgrounds, sometimes featuring patterned textiles or screens, contribute to the overall decorative harmony, echoing Whistler's principles.

His travels also informed his subject matter. Works depicting tropical landscapes suggest journeys to warmer climes, allowing him to explore different light conditions and color palettes. A notable example is Murano (1907), a captivating night scene of the Venetian island famous for its glassmaking. The painting utilizes bold color contrasts and simplified forms to convey the unique atmosphere of Venice after dark, showcasing his ability to adapt his style to diverse subjects and environments.

The Art of the Frame: The Carrig-Rohane Shop

Beyond his accomplishments as a painter, Hermann Dudley Murphy made a lasting contribution to American art through his work as a frame designer and maker. Deeply influenced by Whistler's belief that a frame was integral to the artwork it surrounded, Murphy sought to elevate the craft of frame making in the United States. Around 1903, he co-founded the Carrig-Rohane Shop in Winchester, Massachusetts, where he lived and worked. The name itself, derived from Irish place names associated with his family heritage, evoked a sense of history and craftsmanship.

He established the workshop in collaboration with Charles Prendergast, the brother of artist Maurice Prendergast and a skilled craftsman and artist in his own right, and Walfred Thulin, another talented woodworker and gilder. Carrig-Rohane quickly gained a reputation for producing high-quality, hand-carved, and gilded frames designed in harmony with the paintings they were intended to hold. This philosophy contrasted sharply with the mass-produced, often overly ornate frames common at the time.

Murphy's frame designs drew inspiration from historical European models, particularly Renaissance and Baroque styles, but were adapted with a modern sensibility aligned with the principles of the Arts and Crafts movement. They emphasized simplicity, elegance, fine materials, and meticulous craftsmanship. The designs were often characterized by refined profiles, hand-carved patterns, and carefully applied gilding or finishes that complemented the Tonalist and Impressionist paintings favored by Murphy and his contemporaries. The shop created frames not only for Murphy's own work but also for many leading artists of the day, significantly influencing framing standards in Boston and beyond. The success and reputation of Carrig-Rohane led to its eventual merger with the prominent Vose Galleries of Boston, further solidifying its importance in the art world.

Career, Teaching, and Recognition

Upon returning from Paris in 1896, Murphy settled in Winchester, Massachusetts, which became his base for the remainder of his career. By the early 1900s, he had established himself as a leading figure in the vibrant Boston art scene, often associated with the "Boston School" of painters, which included artists like Edmund C. Tarbell, Frank W. Benson, William McGregor Paxton, and Philip Leslie Hale. While sharing some common ground, Murphy's Tonalist leanings distinguished his work from the more purely Impressionistic focus of some of his peers.

Murphy was also a dedicated educator. He held teaching positions at Harvard University's School of Architecture, instructing students in drawing and painting, and also taught at the Worcester Art Museum School. During summers, he often taught classes on Cape Cod. His teaching philosophy encouraged students to move beyond mere representation, urging them to use "poetic abstraction" to evoke emotional responses in the viewer. This approach reflected his own artistic goals of capturing mood and atmosphere rather than just literal appearances.

His artistic contributions were recognized through various awards and exhibitions. He held successful solo shows and participated in major group exhibitions, including the landmark Armory Show of 1913 in New York City, which introduced European modernism to American audiences on a large scale. His inclusion in such a pivotal exhibition highlights his standing within the American art establishment of the time.

During World War I, Murphy applied his artistic skills to the war effort, serving as a camouflage expert for the United States Shipping Board. His understanding of color theory, light, and shadow proved valuable in developing disruptive patterns to help conceal ships from enemy submarines, demonstrating a practical application of his artistic knowledge.

Notable Relationships and Collaborations

Throughout his career, Murphy maintained important relationships with fellow artists. His collaboration with Charles Prendergast and Walfred Thulin at the Carrig-Rohane Shop was fundamental to his success as a frame designer. This partnership exemplified the Arts and Crafts ideal of collaborative craftsmanship.

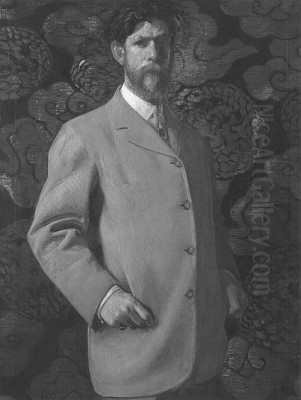

His time in Paris fostered a significant friendship with the acclaimed African American painter Henry Ossawa Tanner. Murphy and Tanner were reportedly roommates for a period, sharing experiences as expatriate art students. Murphy later painted a sensitive and insightful portrait of Tanner, capturing the character of his friend and fellow artist. This portrait remains an important document of their relationship and Tanner's presence in the Parisian art world.

Murphy was also connected to the artistic community in Winchester, which included talented individuals like the painter and illustrator Nelly Littlehale Hartley (later Sohier). He actively participated in local arts initiatives, helping to organize the Winchester Handicraft Society, further promoting the ideals of craftsmanship and artistic collaboration within his community. His connections placed him firmly within the network of influential artists working in and around Boston during its "Golden Age" of painting.

Legacy and Collections

Hermann Dudley Murphy passed away in 1945, leaving behind a rich and multifaceted legacy. As a painter, he was a key proponent of Tonalism in America, skillfully blending its atmospheric qualities with Impressionistic techniques. His landscapes, portraits, and especially his elegant floral still lifes are admired for their subtle beauty, refined execution, and harmonious compositions. His work captured a particular sensibility prevalent in American art at the turn of the twentieth century – one that valued mood, beauty, and quiet contemplation.

His contribution as a frame designer and maker through the Carrig-Rohane Shop was arguably as significant as his painting. He championed the idea of the frame as an essential component of the artwork, promoting designs that were historically informed yet modern in their simplicity and elegance. This work elevated the status of frame making in America and influenced generations of artists and framers to consider the presentation of art more holistically.

As an educator at institutions like Harvard, Murphy influenced numerous students, imparting not only technical skills but also a philosophy that emphasized the expressive potential of art. His encouragement of "poetic abstraction" hinted at the shifts towards modernism that would continue to shape American art in the decades following his peak activity.

Today, Hermann Dudley Murphy's paintings and frames are held in the collections of major American museums, attesting to his enduring importance. His works can be found at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Art Institute of Chicago; the National Academy of Design, New York; the Albright-Knox Art Gallery (formerly Albright Art Gallery), Buffalo; the Dallas Museum of Art; the Cleveland Museum of Art; the Saint Louis Art Museum; and the San Diego Museum of Art, among others. These collections ensure that his contributions to American Tonalism, Impressionism, and the art of the frame continue to be studied and appreciated. He remains a pivotal figure, representing the confluence of refined aesthetics, technical mastery, and innovative craftsmanship in American art history.