Introduction: An Artist Between Eras

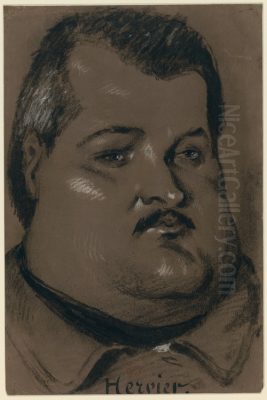

Louis Adolphe Hervier (1818-1879) stands as a fascinating, though often overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century French art. A painter and, perhaps more significantly, a printmaker, Hervier navigated the complex artistic currents that flowed between the waning dominance of Romanticism and the burgeoning movements of Realism and Impressionism. Born into an artistic milieu in Paris, his career was marked by persistent struggle against the established Salon system, yet his unique vision earned him the admiration of influential critics and fellow artists. His work, characterized by evocative depictions of French rural life, coastal scenes, and poignant observations of contemporary events, offers a valuable window into the social and artistic landscape of his time. Hervier's legacy lies not only in his technical skill, particularly in etching, but also in his role as a quiet precursor to the revolutionary changes that would soon sweep the art world.

Artistic Lineage and Early Formation

Hervier's immersion in the art world began at birth. He was born in Paris in 1818, the son of Marc-Antoine Hervier, a miniaturist painter of some note. His father's own artistic training provided a direct link to the Neoclassical tradition, as Marc-Antoine had studied under both the formidable Jacques-Louis David, the leading figure of Neoclassicism, and François-Aubry, another respected artist of the period. This familial connection undoubtedly fostered an environment where artistic pursuits were encouraged and understood from a young age. While the precise details of his earliest instruction are sparse, it's clear that this background provided a foundational understanding of artistic principles.

Formal training followed, most notably under Charles Dusaulx, an artist whose influence on Hervier is less documented but formed part of his academic grounding. However, a more significant mentorship came from Eugène Isabey (1803-1886). Isabey, himself the son of the famous miniaturist Jean-Baptiste Isabey, was a prominent figure associated with the Romantic movement. He was renowned for his dramatic marine paintings and historical scenes, often imbued with a sense of atmospheric turbulence and picturesque detail. Studying with Isabey exposed Hervier to the expressive possibilities of landscape and seascape painting, emphasizing mood, light, and a departure from purely classical constraints. This tutelage likely shaped Hervier's own predilection for atmospheric effects and scenes drawn from everyday life and nature, albeit rendered with his own distinct sensibility.

The Mid-19th Century French Art Scene: A World of Change

To fully appreciate Hervier's journey, one must understand the artistic environment he inhabited. Mid-19th century France was a period of intense artistic debate and transformation. The official art world was largely dominated by the Académie des Beaux-Arts and its annual exhibition, the Paris Salon. Acceptance into the Salon was crucial for an artist's reputation and commercial success, but its jury often favored conservative, academic styles rooted in historical, mythological, or religious themes, executed with a polished finish.

This established order faced challenges from several fronts. Romanticism, championed by artists like Eugène Delacroix and Théodore Géricault earlier in the century, had already introduced a greater emphasis on emotion, individualism, and dramatic subject matter. Concurrently, the Barbizon School emerged, centered around a group of artists who settled near the Forest of Fontainebleau to paint landscapes directly from nature. Figures like Théodore Rousseau, Charles-François Daubigny, Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña, and Jules Dupré sought a more truthful, less idealized depiction of the French countryside, focusing on light, atmosphere, and rural simplicity. Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, though associated with Barbizon, forged his own lyrical path, influencing many with his subtle tonal harmonies.

Furthermore, the seeds of Realism were being sown, most forcefully by Gustave Courbet, who rejected idealized subjects in favor of unvarnished depictions of contemporary life and labor, famously challenging the Salon's authority. Jean-François Millet, another artist often linked to Barbizon, focused on portraying the dignity and hardship of peasant life. It was within this dynamic, often contentious, landscape – marked by the tension between academic tradition and emerging desires for greater naturalism, realism, and individual expression – that Louis Adolphe Hervier sought to make his mark.

Hervier's Artistic Vision: Subjects and Style

Hervier developed a distinctive artistic voice, primarily focusing on landscapes, seascapes, and scenes of provincial life. His travels, particularly to Normandy and the outskirts of Paris, provided rich subject matter. He was drawn to the unpretentious beauty of the everyday: bustling market squares, quiet fishing ports teeming with boats, rustic village streets, weathered windmills, and the humble activities of peasants and fisherfolk. His works often possess a strong sense of place, capturing the specific character and atmosphere of the locations he depicted.

Stylistically, Hervier's work reflects the transitional nature of his era. While influenced by the atmospheric concerns of his teacher Isabey and potentially by the naturalism of British landscape painters like John Constable (whose work had been shown in Paris to great acclaim), Hervier maintained a strong emphasis on drawing and structure. His paintings and watercolors often exhibit a lively, sometimes agitated, brushwork or pen stroke, conveying energy and immediacy. He possessed a keen eye for detail, rendering architectural elements or the rigging of ships with accuracy, yet without sacrificing the overall mood of the scene.

His palette could range from muted, earthy tones, particularly in his rural landscapes, to brighter, more luminous hues in his watercolors, especially those depicting coastal light or market days. He masterfully used light and shadow not just for descriptive purposes but also to create emotional resonance. There's often a slightly melancholic or picturesque quality to his work, a romantic sensibility applied to realistic subjects, distinguishing him from the starker Realism of Courbet or the later, more objective light studies of the Impressionists.

The Struggle for Recognition: Hervier and the Salon

Hervier's relationship with the official art establishment, specifically the Paris Salon, was fraught with difficulty. Despite his evident talent and the support he would later garner from respected critics, his work repeatedly failed to meet the approval of the conservative Salon jury. Between 1837 and 1849, his submissions were rejected an astonishing twenty-three times. This persistent rejection speaks volumes about the challenges faced by artists who deviated, even subtly, from the prevailing academic norms or whose style did not align with the jury's expectations.

The reasons for these rejections likely stemmed from a combination of factors. Perhaps his style was deemed too sketchy or unpolished compared to the smooth finish favored by the Academy. His focus on humble, everyday subjects might have been considered lacking in the 'noble' or 'elevated' themes preferred by the jury. His atmospheric effects, while admired by some, might have been seen as lacking clarity or precision by others. Whatever the specific reasons, this prolonged period of exclusion undoubtedly presented significant professional and perhaps personal hardship for Hervier.

Finally, in 1849, the tide turned, and Hervier's work was accepted for exhibition at the Salon. This marked a crucial turning point, granting him official recognition and allowing his art to be seen by a wider public and critical audience. While acceptance did not guarantee fame or fortune, it was an essential step in establishing a professional career within the highly competitive Parisian art world. This hard-won success underscores Hervier's perseverance in the face of adversity.

A Master Etcher: Hervier's Contribution to Printmaking

While Hervier worked proficiently in oil and watercolor, his contribution to the art of etching is particularly noteworthy. The mid-19th century witnessed a significant revival of interest in etching as an original art form, moving away from its primary use for reproductive purposes. Artists began exploring the medium's unique expressive potential, its capacity for rich tonal variation, and the intimacy of the artist's direct touch on the plate. Hervier was a key participant in this Etching Revival.

His etchings are celebrated for their technical mastery and distinctive aesthetic. He skillfully manipulated ink and plate tone to achieve remarkable atmospheric effects, capturing nuances of light, weather, and texture. His line work could be both delicate and vigorous, adapting to the subject matter, whether rendering the intricate details of a cityscape or the broad, windswept expanse of a coastal scene. Critics praised the unique "juiciness" (or richness) of his inks and the painterly quality he achieved in black and white.

Hervier's approach to etching often mirrored his subjects in painting and watercolor: views of ports, villages, rural landscapes, and urban corners. He brought the same sensitivity to observation and mood to his prints. His work in this medium can be compared to that of other great 19th-century etchers. While perhaps lacking the dramatic intensity of Charles Meryon's Parisian visions or the later, refined elegance of James McNeill Whistler's prints, Hervier's etchings possess a unique blend of picturesque charm, atmospheric depth, and technical ingenuity. His prints stand alongside those of contemporaries like Charles Jacque, another artist known for his rural scenes in both painting and etching, as significant contributions to the medium during this fertile period. His mastery of etching cemented his reputation among connoisseurs and fellow artists, even when his paintings faced challenges.

Witness to History: The June Days of 1848

Beyond his landscapes and genre scenes, Hervier also turned his artistic eye to contemporary historical events, most notably the June Days Uprising in Paris in 1848. Following the February Revolution which overthrew King Louis-Philippe, tensions escalated between the provisional government and the working classes demanding social reforms. The closure of the National Workshops, designed to provide work for the unemployed, sparked a massive, spontaneous uprising by Parisian workers from June 23rd to 26th. The government, led by General Cavaignac, responded with brutal force, deploying the army and the National Guard to crush the insurrection. The fighting was fierce, resulting in thousands of deaths and arrests.

Hervier captured the immediacy and brutality of these events in a series of powerful watercolors. These works function almost as reportage, depicting street barricades, confrontations between insurgents and soldiers, and the grim aftermath of the conflict. Unlike grand, allegorical history paintings, Hervier's watercolors possess a raw, documentary quality. They convey the chaos, violence, and human cost of the uprising with unflinching directness. His viewpoint often seems to be that of an observer caught within the unfolding drama, lending the scenes a palpable sense of urgency and authenticity.

These depictions of the June Days reveal Hervier's engagement with the social and political turmoil of his time. They stand as important historical documents, offering a visual counterpoint to official narratives and capturing the lived experience of revolution on the streets of Paris. In their focus on contemporary reality and their unvarnished portrayal of conflict, these works align with the broader shift towards Realism, exemplified by artists like Honoré Daumier, whose caricatures and paintings also provided sharp social commentary. Hervier's June Days series demonstrates his versatility and his willingness to tackle difficult, contemporary subject matter.

Critical Acclaim and Artistic Circles

Despite his early struggles with the Salon, Hervier did not work in isolation, nor was his talent entirely unrecognized. He garnered support from some of the most influential art critics of his day. Figures like Théophile Gautier, a renowned poet, novelist, and critic known for his advocacy of "art for art's sake," recognized the quality of Hervier's work. Champfleury, a novelist and critic who championed Realism and admired artists depicting everyday life, also wrote favorably about him. Other prominent voices, including the widely read critic Jules Janin and the perceptive Goncourt brothers (Edmond and Jules), who were astute observers of contemporary art and society, acknowledged his abilities.

This critical support was significant. In an era before the proliferation of independent galleries, positive reviews in major journals could substantially impact an artist's reputation and prospects. The backing of such respected figures helped to validate Hervier's artistic vision, particularly his skill in capturing atmosphere and his sensitive portrayal of French life, even when the Salon remained hesitant.

Furthermore, Hervier moved within artistic circles that connected him to other significant painters. His association with the Barbizon group, though perhaps informal, placed him in proximity to artists dedicated to landscape painting from nature, such as Corot and Jacque. He was also acquainted with Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, known for his genre scenes and Orientalist subjects, and the Dutch painter Johan Barthold Jongkind, whose pre-Impressionist marine and city views, characterized by fluid brushwork and attention to light, share some affinities with Hervier's own work, particularly in watercolor. His connection with Paul Huet, a landscape painter associated with Romanticism, further illustrates his engagement with the diverse artistic trends of the period. These connections provided opportunities for mutual influence and support within the Parisian art community.

Hervier's Place in Art History: Precursor and Individualist

Evaluating Louis Adolphe Hervier's precise place in the grand narrative of art history requires acknowledging his position as a transitional figure. He was deeply rooted in the traditions of landscape and genre painting inherited from Romanticism and influenced by earlier Dutch and British masters, yet his work also anticipated future developments. His emphasis on capturing atmospheric effects, his interest in fleeting moments of light, and his focus on contemporary, everyday subjects – ports, markets, rural labor – all prefigure concerns that would become central to Impressionism.

While not an Impressionist himself – his work generally retains a stronger sense of structure and narrative than that of artists like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro – Hervier's sensitivity to light and atmosphere, particularly evident in his watercolors and etchings, points towards the direction French art was heading. Some critics and historians consider him a precursor, one of the artists who helped pave the way for the Impressionist revolution by legitimizing landscape and modern life as subjects worthy of serious artistic attention and by experimenting with techniques to capture transient effects.

However, Hervier remains distinct. He forged his own path, blending detailed observation with a personal, often picturesque or slightly melancholic, sensibility. He was a chronicler of a specific vision of France – its coasts, its countryside, its working people – rendered with technical skill and genuine feeling. His mastery of etching secured him a firm place in the history of printmaking. Though perhaps overshadowed in popular recognition by the more radical innovators who followed him, Hervier's persistence, his unique blend of influences, and his sensitive portrayal of his world earn him a respected position as a dedicated and accomplished artist of the 19th century.

Legacy and Conclusion

Louis Adolphe Hervier died in Paris in 1879, the same year the fourth Impressionist exhibition was held. His life spanned a period of profound artistic change, and his career reflects the challenges and opportunities of that era. He began under the influence of Romanticism, navigated the rise of Realism and the Barbizon School, persevered through repeated rejection by the Salon establishment, and ultimately created a body of work that resonated with influential critics and pointed towards the future of landscape painting.

His legacy endures primarily through his evocative landscapes and genre scenes, particularly his masterful etchings and atmospheric watercolors. Works like his depictions of Norman ports, Parisian markets, or the dramatic June Days uprising showcase his keen observational skills, his technical versatility, and his ability to capture the essence of a place or moment. He remains admired for his dedication to his craft, especially in printmaking, where he contributed significantly to the Etching Revival.

While not achieving the household-name status of some contemporaries like Corot or the later Impressionists, Hervier's art is preserved in major museum collections, including the Louvre in Paris and institutions internationally, allowing contemporary audiences to appreciate his unique vision. He stands as a testament to artistic perseverance and represents an important link in the chain of 19th-century French art, an artist who faithfully chronicled his world while subtly anticipating the modern gaze. Louis Adolphe Hervier's work offers a quiet but compelling insight into the soul of France during a time of transformation.