Georges Ferdinand Bigot (1860-1927) stands as a unique figure in the annals of art history, a French painter, illustrator, and caricaturist whose most significant contributions arose from his extended sojourn in Meiji-era Japan. His work offers an invaluable, albeit sometimes controversial, Western lens through which to view a nation undergoing profound transformation. Bigot's keen observational skills, coupled with a sharp satirical wit, allowed him to capture the nuances, absurdities, and social shifts of Japanese society as it navigated the complex path of modernization and Westernization. His legacy is twofold: a rich visual archive for historians and a body of work that played a role in the development of modern Japanese caricature.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Paris

Born in Paris on April 7, 1860, Georges Ferdinand Bigot was the eldest of five children. His early life was marked by hardship; his father, a military officer, perished in war, leaving the family in challenging economic circumstances. Despite these difficulties, his mother recognized and supported her son's artistic inclinations. This maternal encouragement was crucial, enabling Bigot to pursue formal art training from a young age.

At the tender age of twelve, Bigot enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the epicenter of academic art training in France. There, he studied under influential masters of the time. Among his tutors was Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), a towering figure of French academic painting, renowned for his meticulously detailed historical and Orientalist scenes. Gérôme's emphasis on precise draughtsmanship and realistic depiction would have undoubtedly left an imprint on the young Bigot. Another significant mentor was Emile Auguste Carolus-Duran (1837-1917), a celebrated society portraitist and a teacher known for encouraging a more direct and painterly approach, influenced by artists like Velázquez. This blend of rigorous academic training and exposure to more contemporary painterly concerns provided Bigot with a solid technical foundation.

The Paris of Bigot's youth was a vibrant artistic hub. The Impressionist movement, with artists like Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), was challenging academic conventions, though the École des Beaux-Arts largely remained a bastion of traditionalism. It was within this dynamic environment that Bigot honed his skills, initially focusing on painting and drawing in a more conventional European style.

The Call of the Orient: Journey to Japan

A pivotal moment in Bigot's artistic development occurred in 1878 with the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) held in Paris. This grand event showcased cultures and industries from around the globe, and the Japanese pavilion, with its exquisite crafts, textiles, and artworks, captivated many Western artists and intellectuals. This phenomenon, known as Japonisme, was already taking root, influencing artists like James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), Edgar Degas (1834-1917), and Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) with its novel compositional approaches, flattened perspectives, and decorative motifs found in ukiyo-e woodblock prints.

For Bigot, the encounter with Japanese art, particularly the Hokusai Manga – the sketchbooks of Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) teeming with lively depictions of everyday life, flora, fauna, and fantastical creatures – was profoundly inspiring. Hokusai's dynamic lines and keen observation of human nature likely resonated with Bigot's own burgeoning interest in caricature and social commentary. This exposure ignited a deep curiosity about Japan, a land that seemed both exotic and artistically rich.

Fueled by this fascination, Bigot made the life-altering decision to travel to Japan. In 1882, at the age of 22, he embarked on the long journey, arriving in a country that was in the midst of the Meiji Restoration – a period of rapid modernization, industrialization, and Westernization following centuries of feudal rule and relative isolation. This was a Japan grappling with new political systems, social customs, technologies, and foreign influences, providing a fertile ground for an observant artist like Bigot.

An Artist in Meiji Japan: Teaching and Observation

Upon his arrival in Japan, Bigot quickly immersed himself in his new environment. He secured a position as a professor of watercolor painting at the Rikugun Shikan Gakkō (Imperial Japanese Army Academy) in Tokyo. This role provided him with a degree of financial stability and a unique vantage point from which to observe the interactions between Japanese traditions and encroaching Western influences, particularly within an institution dedicated to modernizing the nation's military.

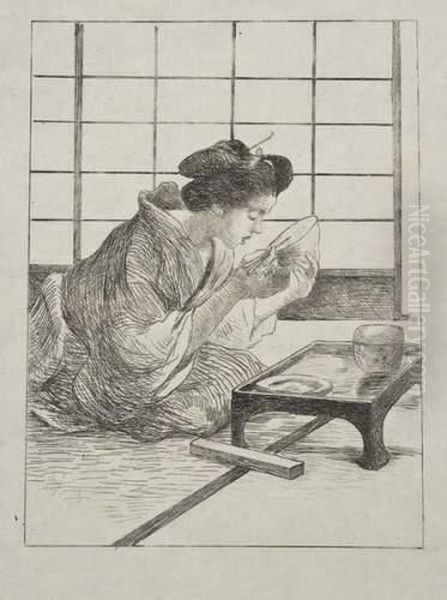

Beyond his teaching duties, Bigot was a prolific artist, constantly sketching and painting the world around him. He was fascinated by the everyday life of the Japanese people – their customs, attire, festivals, and street scenes. His works from this period capture a wide array of subjects, from traditional geishas and samurai (though the samurai class had been officially abolished, their legacy and imagery persisted) to newly established Western-style institutions and the often-awkward adoption of Western dress and manners by some Japanese.

Bigot's artistic approach in Japan was multifaceted. He continued to produce paintings and watercolors, often depicting scenes with a realistic, ethnographic quality. However, it was his talent for illustration and caricature that truly flourished. He possessed an acute eye for the subtleties of human behavior and societal change, translating his observations into incisive and often humorous visual commentaries. He learned and adapted techniques, including woodblock printing, though he primarily worked with Western methods like etching, which he introduced or popularized further among some Japanese artists.

His interactions with Japanese artists were also significant. While the provided information names Yokoyama Matsusaburō (1838-1884), a pioneering photographer who also painted in a Western style, as a student, Bigot's influence likely extended more broadly through his teaching and published works. He was part of a wave of foreign artists and educators, such as the Italian painter Antonio Fontanesi (1818-1882), who were invited to Japan to teach Western artistic techniques as part of the Meiji government's modernization efforts.

The Sharp Pen of Satire: Tobae and Social Commentary

One of Georges Ferdinand Bigot's most enduring legacies in Japan was his contribution to the field of satirical journalism. He founded and edited a satirical magazine titled Tobae , named after Toba Sōjō, a Heian-period monk traditionally credited with creating some of the earliest examples of Japanese narrative scroll painting with humorous and animal caricatures (chōjū-giga). The choice of name was deliberate, linking his modern satirical endeavor to a historical Japanese tradition of humorous art.

Tobae, published primarily in French but with some Japanese text, became a platform for Bigot's sharp critiques of Japanese society, politics, and the often-clumsy process of Westernization. His cartoons lampooned government officials, commented on social inequalities, and highlighted the cultural clashes and misunderstandings that arose from Japan's rapid opening to the West. His style was direct, often employing exaggerated features and comical situations to make his point, reminiscent of European satirical traditions exemplified by artists like Honoré Daumier (1808-1879) in France or British publications like Punch.

Before Tobae, Bigot had also been involved with La Vie Japonaise, another publication that featured his illustrations. Through these magazines, Bigot introduced Western-style caricature and political cartooning to a wider audience in Japan. His work, along with that of other foreign artists like the British Charles Wirgman (1832-1891), who founded Japan Punch, played a crucial role in stimulating the development of modern Japanese manga and satirical illustration. These publications provided a new visual language for social and political commentary.

Bigot's satire was not always gentle. He depicted Japanese people in various states of transition, sometimes appearing bewildered by Western customs, other times eagerly or awkwardly adopting them. His portrayal of foreign residents in Japan was also subject to his critical eye. While his work is valued for its historical insight, some modern interpretations also note an element of colonial condescension or a stereotypical "Orientalist" gaze in certain depictions, reflecting the prevailing European attitudes of the era. Nevertheless, the impact of Tobae was significant, though its pointed critiques eventually led to its cessation in 1897 due to political pressure, a testament to its perceived influence.

Key Works and Artistic Style

Georges Ferdinand Bigot's oeuvre is diverse, encompassing paintings, watercolors, etchings, and numerous illustrations and caricatures. His artistic style, while rooted in his French academic training, evolved to suit his subject matter and satirical intent in Japan.

One of his notable early publications in Japan was _Croquis japonais_ (Japanese Sketches), published in Tokyo in 1886. This album contained a series of 29 black-and-white etchings that showcased various aspects of Japanese life, from street vendors and laborers to more intimate domestic scenes and landscapes. These etchings demonstrate his skill in draughtsmanship and his ability to capture character and atmosphere with economical lines. Works from this period, such as _La Servante_ (The Servant Girl), _Tailleur_ (The Tailor), and other untitled pieces, often printed on Japanese paper, highlight his observational acuity.

His satirical cartoons, particularly those published in Tobae and other periodicals, are perhaps his most famous contributions. A series like _Keikan no tabō_ (The Policeman's Busy Day, or Amusing Log of a Policeman) humorously depicted the daily routines and challenges faced by the newly Westernized Japanese police force, often highlighting their struggles with new uniforms, equipment, and societal expectations. These works were characterized by expressive figures, dynamic compositions, and a clear narrative, making them accessible and engaging.

Bigot also created works for other purposes, such as illustrations for the Épinal series, including pieces like _Intérieur japonais_ (Japanese Interior), which provided detailed views of Japanese domestic spaces for a European audience. His painting _Fête au sanctuaire Tōshōgu_ (Festival at Tōshōgū Shrine) indicates his interest in capturing the color and vibrancy of traditional Japanese cultural events.

His style blended realism, particularly in his more ethnographic depictions, with the deliberate exaggeration and simplification characteristic of caricature. He was adept at capturing physiognomy and gesture, conveying personality and social status through visual cues. The influence of Japanese art, especially ukiyo-e, can be seen in some of his compositions and his focus on everyday life, though his primary mode of expression remained rooted in Western traditions of drawing and printmaking. His use of etching, a Western technique, was significant in itself, offering a different aesthetic from traditional Japanese woodblock prints.

Collaborations and Influences

During his seventeen years in Japan and subsequently, Georges Ferdinand Bigot engaged in several artistic and journalistic collaborations that amplified his reach and impact. His partnership with the British artist and journalist Charles Wirgman is particularly noteworthy. Wirgman, who had arrived in Japan much earlier and founded Japan Punch in 1862, was a pioneer of satirical cartooning in the country. Bigot and Wirgman moved in similar expatriate circles and shared an interest in commenting on Japanese society through caricature. They both taught Western art techniques and influenced a generation of Japanese artists keen to learn these new forms of expression.

Bigot's own magazine, Tobae, sometimes featured the work of other artists, including the American cartoonist Frank Arthur Nankivell (1869-1959), indicating an international exchange of satirical styles. In France, after his return, he collaborated with the journalist Fernand Ganesco on a book published in 1895, though the specifics of this collaboration would require further research beyond the provided information.

He also contributed illustrations to prominent European publications. His work appeared in the British illustrated newspaper _The Graphic_, which was known for its high-quality engravings and global coverage. This provided a platform for his depictions of Japanese life and his satirical observations to reach a wider Western audience. Furthermore, his association with the French publishing house Pélerin, known for its popular illustrated materials, saw him create numerous illustrations focusing on themes from Japan and French Indochina, showcasing daily life, customs, and architecture for French readers.

The influence of Japanese art on Bigot himself, particularly the work of Katsushika Hokusai, was a formative element in his decision to travel to Japan and likely informed his dynamic approach to capturing human figures and everyday scenes. Conversely, Bigot, through his teaching and publications, introduced Western techniques like etching and the specific conventions of European satirical drawing to Japanese artists. This cross-cultural exchange was a hallmark of the Meiji era, and Bigot was an active participant in this dialogue. His work, therefore, sits at an interesting intersection of French artistic traditions and the burgeoning field of modern Japanese visual culture.

Return to France and Later Career

In 1899, after seventeen transformative years in Japan, Georges Ferdinand Bigot returned to France. The reasons for his departure are not explicitly detailed in the provided summary but could have been multifaceted, possibly including changing political sensitivities in Japan towards foreign satire, personal reasons, or a desire to re-engage with the Parisian art world.

Back in his native country, Bigot continued his artistic career. He did not abandon the themes and experiences that had so profoundly shaped his work. He continued to draw upon his memories and sketches of Japan, producing landscapes and genre scenes. His skills as a satirist also remained in demand. He contributed satirical cartoons and illustrations to various French magazines, applying his critical eye to French society and politics, much as he had done in Japan.

His time in Japan had given him a unique perspective and a wealth of subject matter that distinguished him from many of his French contemporaries. He participated in exhibitions in France, showcasing his Japanese-themed works as well as his newer creations. He also published books and albums, further disseminating his art and observations. While the Parisian art scene was then dominated by Post-Impressionist figures like Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), and the emerging Fauvist movement led by Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Bigot carved out his own niche, drawing on his unique experiences abroad.

His involvement with colonial themes continued, as evidenced by his illustrations related to French Indochina for Pélerin. This suggests an ongoing engagement with the representation of non-European cultures, though, as noted earlier, this aspect of his work is sometimes viewed through a critical lens regarding colonial attitudes of the period. Despite this, his artistic output in France demonstrated a continued vitality and a commitment to his craft until his death in Paris in 1927 (some sources state 1928, but 1927 is more commonly cited and aligns with the primary provided text).

The Russo-Japanese War: A Cartoonist on the Front Lines

A fascinating, though perhaps less universally known, chapter in Georges Ferdinand Bigot's later career was his involvement as a correspondent during the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). This conflict, a major clash between a rising Asian power and a European empire, captured global attention. Bigot, with his extensive experience in Japan and his established reputation as an illustrator and keen observer, was a natural choice for such an assignment.

In 1904, he traveled to the Russian Far East as a special correspondent. His role was to document the war not through photography, which was becoming more common in war reporting, but through his distinctive drawings and cartoons. These war-time illustrations were widely circulated and proved popular, offering a vivid and often humanizing perspective on the conflict. His sketches captured scenes from the front lines, the lives of soldiers, and the broader impact of the war.

During this period, he also produced a work titled something akin to "Illustrated Album of the Sino-Japanese War" . If it indeed refers to the Russo-Japanese war, his "photographs" would have been his drawings, presented as a visual record. These illustrations, disseminated through newspapers and magazines, played a role in shaping public perception of the war in Europe.

This experience as a war correspondent further underscores Bigot's versatility and his commitment to using his art as a means of reportage and commentary. It placed him in a tradition of artist-correspondents who documented conflicts before photography became the dominant medium for war journalism, artists like Winslow Homer (1836-1910) during the American Civil War.

Bigot and His Contemporaries: A Wider Artistic Context

Georges Ferdinand Bigot's artistic career (1860-1927) spanned a period of immense artistic innovation and diversification in Europe and beyond. When he was training in Paris, Impressionism, led by figures like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), was already established, though academic art, as taught by his mentor Jean-Léon Gérôme, still held considerable sway. The work of Édouard Manet (1832-1883), a pivotal figure bridging Realism and Impressionism, would also have been part of the artistic discourse.

During Bigot's time in Japan (1882-1899), Post-Impressionism was flourishing in Europe with artists like Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, and Georges Seurat (1859-1891) pushing the boundaries of color and form. The Art Nouveau movement, with its organic lines and decorative emphasis, was also gaining prominence, exemplified by artists like Alphonse Mucha (1860-1939), a direct contemporary of Bigot in terms of birth year, and Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) in Vienna. The biting social satire in the works of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901), chronicling Parisian nightlife, offers an interesting parallel to Bigot's satirical eye, albeit in a different cultural context.

Bigot's focus on Japan aligned with the broader Western fascination known as Japonisme, which influenced many of these artists, including James McNeill Whistler, Edgar Degas, and Mary Cassatt (1844-1926). However, Bigot's engagement was unique; rather than merely incorporating Japanese stylistic elements into Western painting from afar, he lived and worked within Japan, producing work primarily about Japan, often for a Japanese and expatriate audience initially, as well as for consumption back in Europe.

By the time Bigot returned to France and continued his career into the early 20th century, modern art movements were in full swing. Fauvism, led by Henri Matisse, and Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) and Georges Braque (1882-1963), were revolutionizing artistic expression. Expressionism was also taking hold in Germanic countries with artists like Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980). Bigot's style, rooted in 19th-century realism and caricature, remained distinct from these avant-garde developments. He was less an innovator of artistic form in the modernist sense and more a skilled practitioner applying established Western techniques to a unique cross-cultural context, with a particular talent for narrative and satirical illustration. His contemporary in Japan, Kawanabe Kyōsai (1831-1889), was a Japanese painter known for his own often humorous and caricatural style, bridging traditional Japanese painting with a keen observation of the changing times.

Legacy and Historical Impact

The legacy of Georges Ferdinand Bigot is multifaceted. Primarily, he is remembered as a critical visual chronicler of Meiji-era Japan. His vast output of sketches, etchings, and cartoons provides an invaluable historical record of a society in flux, capturing the tensions, absurdities, and adaptations inherent in Japan's rapid modernization and Westernization. His works are frequently consulted by historians and sociologists studying this period, and many of his images continue to be reproduced in Japanese textbooks as illustrations of Meiji society, a testament to their perceived accuracy and evocative power.

Bigot's role in the development of Japanese manga and satirical art is also significant. Alongside figures like Charles Wirgman, he introduced and popularized Western forms of caricature and the concept of the satirical magazine. Tobae served as an important early example and likely inspired Japanese artists to adopt and adapt these methods for their own social and political commentary. In this sense, he can be seen as a catalyst in the cross-cultural exchange that contributed to the rich tradition of Japanese graphic arts.

His work also offers a window into European perceptions of Japan and the broader phenomenon of Orientalism in the late 19th century. While his observations were often acute, they were inevitably filtered through his own cultural background and the prevailing colonial attitudes of the time. Some of his depictions have been criticized for perpetuating stereotypes or for a sense of Western superiority. This complexity does not diminish the historical value of his work but adds another layer for critical analysis. He documented not only Japan but also the Western gaze upon it.

In France, while perhaps not as central to the major art movements of his time, he maintained a career as an illustrator and satirist, contributing to the popular visual culture of the period. His experiences in Japan provided him with a unique artistic identity. The very existence of collections of his work, such as the book "Georges Bigot and Japan, 1882-1899," underscores the scholarly interest in his specific contribution to art history and Franco-Japanese cultural relations.

Exhibitions and Enduring Recognition

The continued interest in Georges Ferdinand Bigot's work is evidenced by various exhibitions held long after his death, particularly in Japan, where his art holds special historical significance.

A major exhibition was held in Tokyo in 1987. The comprehensive catalogue produced for this event, reportedly featuring 773 illustrations divided into color and black-and-white sections, indicates the breadth of his oeuvre and the scholarly attention it received. Such an extensive retrospective would have played a crucial role in re-introducing his work to a contemporary audience and solidifying his reputation.

In 2003, the Yokohama Museum of Art hosted an exhibition dedicated to Bigot's sketches and other artworks created during his time in Japan. Yokohama was one of the first Japanese ports opened to foreign trade and had a significant expatriate community during the Meiji era, making it a fitting location to showcase the work of an artist who so vividly documented this period of cross-cultural encounter.

More recently, in 2021, the Utsunomiya Museum of Art featured works by Bigot, including pieces like Fête au sanctuaire Tōshōgu. The inclusion of his art in museum exhibitions nearly a century after his death highlights its enduring artistic merit and historical importance. These exhibitions allow new generations to engage with his unique perspective on Meiji Japan and appreciate his skill as an observer and illustrator.

The preservation of his works in museum collections and the ongoing scholarly research into his life and art ensure that Georges Ferdinand Bigot remains a recognized, if specialized, figure in the history of both French and Japanese art, and a key visual source for understanding a pivotal era in Japanese history.

Conclusion

Georges Ferdinand Bigot was more than just a foreign artist in Japan; he was an engaged, perceptive, and often critical commentator on a society undergoing one of its most dramatic transformations. His journey from the academic halls of Paris's École des Beaux-Arts to the bustling, changing streets of Meiji Japan resulted in a body of work that is both historically invaluable and artistically engaging. Through his paintings, etchings, and particularly his satirical cartoons in publications like Tobae, Bigot captured the zeitgeist of an era, documenting the cultural collisions, societal shifts, and human experiences of Japan's modernization.

While his perspective was undeniably that of a 19th-century European, and his work can be analyzed through the lens of Orientalism and colonial attitudes, its richness lies in its detailed observation and its pioneering role in Japanese satirical art. He left behind a visual legacy that continues to inform our understanding of Meiji Japan and the complex dynamics of East-West cultural encounters. His art serves as a vivid reminder of how individual artists can become crucial chroniclers of their times, offering insights that transcend mere historical fact to touch upon the human condition itself.