Louis Icart stands as a quintessential figure of the Art Deco era, an artist whose name became synonymous with the sophisticated, often sensual, depictions of women that defined the visual culture of Paris and New York in the 1920s and 1930s. A prolific French painter, illustrator, and particularly, etcher, Icart captured the zeitgeist of a generation embracing modernity, glamour, and a newfound sense of freedom. His works, primarily etchings enhanced with delicate hand-colouring, continue to enchant collectors and art lovers, offering a window into a world of elegance, romance, and subtle wit. His unique blend of traditional influences and modern sensibilities secured his place not just within the Art Deco movement, but in the broader narrative of early 20th-century European art.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Toulouse

Louis Justin Laurent Icart was born in Toulouse, in the south of France, on December 9, 1888. From a young age, he displayed a natural inclination towards the arts, particularly drawing and sketching. His fascination was especially captured by the world of fashion, a theme that would remain central throughout his artistic career. Growing up during a period of significant stylistic transition, the late Belle Époque, Icart witnessed firsthand the shift from the elaborate, corseted fashions of the late 19th century towards the sleeker, more liberated silhouettes that would characterize the early 20th century.

His innate talent did not go unnoticed. While initially pursuing a more conventional path, potentially in banking like his father, his artistic passion proved undeniable. His aunt, who owned a millinery shop, recognized his flair for design and encouraged his pursuits. It was through sketching hats and fashionable attire for her business that Icart began to hone his skills, developing the fluid lines and keen eye for detail that would later define his mature work. This early immersion in the world of haute couture provided him with an intimate understanding of fabric, form, and the way clothing could express personality and the spirit of the times.

Toulouse, while a significant regional center, could not contain his burgeoning ambition. The magnetic pull of Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world and fashion, beckoned. Armed with his portfolio and youthful enthusiasm, Icart made the pivotal decision to move to the city that would become both his home and his greatest source of inspiration.

Arrival in Paris and the Dawn of a Career

In 1907, Louis Icart arrived in Paris, stepping into the vibrant heart of artistic innovation and cultural ferment. The city was alive with the energy of Fauvism, the burgeoning ideas of Cubism, and the lingering elegance of the Art Nouveau style, which was gradually giving way to new aesthetics. Icart quickly immersed himself in this stimulating environment. Initially, he found work leveraging his early experience, creating sketches and designs for major fashion houses and postcards featuring glamorous women.

This period was crucial for his development. Working within the commercial sphere of fashion illustration allowed him to refine his draughtsmanship and speed, capturing the essence of a pose or garment with quick, confident strokes. His sketches from this time already show his ability to convey movement and personality, reflecting the ongoing evolution of fashion towards greater simplicity and dynamism. He absorbed the atmosphere of the city – the chic cafes, the bustling boulevards, the theatres, and the intimate salons – all of which would later populate his canvases and copper plates.

However, Icart's ambitions extended beyond commercial illustration. He was drawn to the more traditional fine arts, particularly painting and printmaking. He began experimenting seriously with etching, a technique that allowed for fine detail, reproducible images, and the potential for subtle tonal variations through methods like aquatint and drypoint. This medium perfectly suited his linear style and his interest in capturing delicate textures and expressive contours. His move towards etching marked a significant step in establishing himself as an independent artist, distinct from his work as a fashion illustrator.

Defining the Icart Style: Art Deco Sensibilities

Louis Icart's mature style crystallized during the height of the Art Deco movement in the 1920s and 1930s, and he became one of its most recognizable visual interpreters. His art is characterized by a unique synthesis of influences, blending the elegance and lightness of 18th-century French Rococo masters with modern sensibilities and techniques. One can see echoes of the playful charm found in the works of Jean-Antoine Watteau, the sensual grace depicted by François Boucher, and the intimate scenes favoured by Jean-Honoré Fragonard.

Yet, Icart was undeniably a man of his time. His work absorbed elements from Impressionism, particularly the focus on fleeting moments, contemporary life, and the effects of light, reminiscent perhaps of Edgar Degas's dancers or Pierre-Auguste Renoir's depictions of Parisian society. There are also hints of Symbolism in the sometimes enigmatic or allegorical nature of his subjects, perhaps drawing subtle inspiration from artists like Odilon Redon or Gustave Moreau, though Icart's approach remained distinctly more decorative and less overtly mystical. His focus on elongated forms and decorative patterns also aligns him with contemporaries like the fashion illustrator Erté (Romain de Tirtoff), though Icart's work often possessed a softer, more painterly quality.

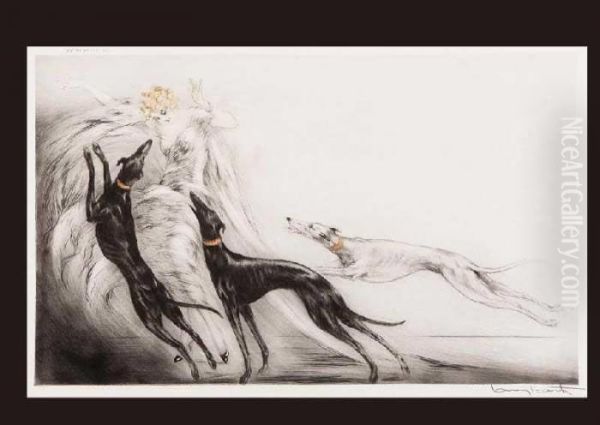

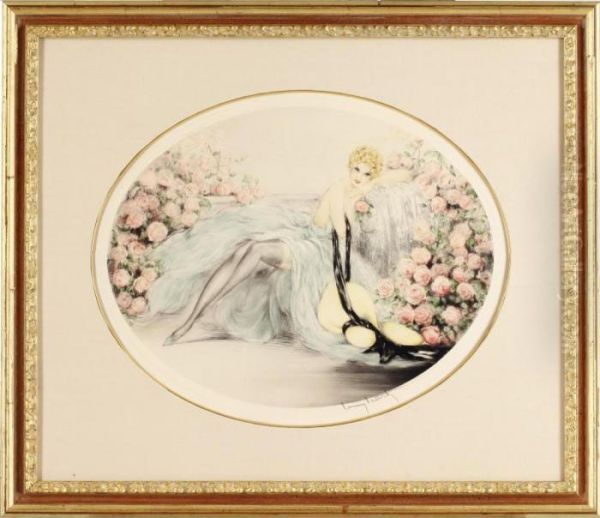

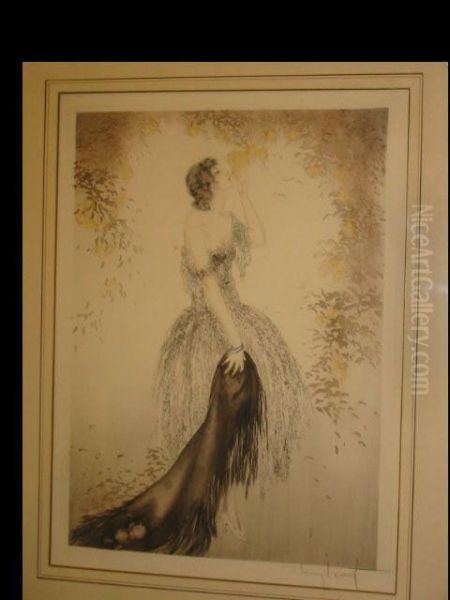

The quintessential Icart subject is the modern woman – elegant, alluring, sometimes mischievous, and embodying the newfound freedoms of the era. His women are often depicted in luxurious interiors, interacting playfully with pets (greyhounds and borzois were favourites), lounging suggestively on sofas, or caught in moments of intimate reverie. He rendered them with flowing, calligraphic lines, emphasizing their grace and movement. His colour palette, often applied by hand to his etchings, tended towards soft pastels or vibrant, jewel-like tones, enhancing the decorative appeal and emotional mood of the scene. A characteristic blend of sophistication, sensuality, and a light, romantic humour pervades his oeuvre, making his style instantly identifiable. Unlike the bolder, more geometric abstractions of some Art Deco artists like Tamara de Lempicka, Icart maintained a connection to representational grace and charm.

The Crucible of War: Art as Solace

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 interrupted Icart's burgeoning career. Like many men of his generation, he was called to serve in the French military. He saw action as an aerial photographer and pilot, experiencing the horrors and trauma of modern warfare firsthand. This period inevitably left a deep mark on him. Far from the glamorous salons of Paris, the stark realities of the battlefield presented a brutal contrast to the world he typically depicted.

During the conflict, art became a crucial outlet for Icart, a way to process his experiences and find solace amidst the chaos. He reportedly sketched and painted constantly, using whatever materials were available, sometimes even scraps of paper or canvas found near the front lines. While few works directly depicting the war itself are prominent in his known oeuvre, the experience likely deepened his appreciation for beauty, life, and perhaps the fleeting nature of joy, themes subtly present in his post-war creations.

His time in the military, particularly working with aerial reconnaissance, may have also subtly influenced his perspective and compositions, perhaps fostering an eye for dynamic angles or broad views, although his primary focus remained intimate human scenes. Upon returning from the war, he threw himself back into his art with renewed vigour, eager to recapture the elegance and joie de vivre that the conflict had threatened to extinguish. The post-war years would prove to be his most prolific and successful period.

Fanny: Muse and Lifelong Companion

A significant figure in both Louis Icart's life and art was his wife, Fanny Volmers. Described as a stunningly beautiful former fashion model, possibly working for the House of Paquin, Fanny became Icart's muse shortly after his return from the war. They married, and their partnership endured throughout his life. Fanny's image permeates Icart's work; she is widely believed to be the model for many of his most famous etchings and paintings.

Her features – often depicted with an air of sophisticated allure, sometimes playful, sometimes languid – became central to the "Icart woman." Whether reclining elegantly on a chaise lounge, adjusting a stocking, or caught in a moment of laughter, the figure often identified as Fanny embodies the idealised femininity that captivated Icart's audience. Her presence in his work adds a layer of personal intimacy to his depictions of glamour and romance.

The collaboration between artist and model-wife was clearly a fruitful one. Fanny provided not just a physical likeness but also, presumably, inspiration and support for his artistic endeavours. Her background in the fashion world likely complemented Icart's own interests, creating a shared understanding of the elegance and style they sought to portray. Their home in Montmartre, overlooking Paris, became a backdrop for many of his compositions, further intertwining their life and his art. The enduring image of Fanny in his work highlights the importance of personal connection and inspiration in shaping an artist's vision.

Mastering the Medium: Etching, Drypoint, and Aquatint

While Louis Icart worked in oils and watercolours, he achieved his greatest fame and commercial success through his mastery of printmaking techniques, particularly etching, drypoint, and aquatint, often combined and enhanced with hand-colouring. Etching involves coating a copper plate with a waxy ground, drawing through the ground with a needle to expose the metal, and then immersing the plate in acid, which bites into the exposed lines. This process allowed Icart to achieve the fine, fluid lines characteristic of his style.

He frequently employed drypoint, where the image is scratched directly onto the copper plate with a sharp needle. This technique creates a slightly blurred, velvety line known as a "burr," adding richness and texture to the print. Aquatint, another etching variant, allowed him to create tonal areas rather than just lines. By applying a porous ground of resin dust to the plate and selectively exposing areas to acid, he could achieve subtle washes of tone, similar to watercolour effects, which provided depth and atmosphere to his compositions.

Many of Icart's most sought-after prints are combination etchings, utilizing lines created by acid etching and drypoint, tonal areas from aquatint, and then meticulously hand-coloured, often with watercolours or gouache, by skilled artisans working under his supervision or sometimes by Icart himself. This final step brought the images to life, adding vibrancy and individuality to each print within an edition. His technical proficiency, reminiscent in its delicacy perhaps of earlier masters of etching like Francisco Goya, though applied to vastly different subject matter, allowed him to produce a remarkable body of work, estimated at over 500 different etchings throughout his career.

Recognizing his international appeal, particularly in the United States, Icart often produced his prints in two editions: one intended for the European market and another, frequently utilizing drypoint more heavily, for American distribution. This practice catered to different tastes and expanded his reach, contributing to his widespread popularity on both continents.

Iconic Works and Enduring Themes

Louis Icart's vast output includes numerous works that have become iconic representations of the Art Deco era. His subjects often revolved around themes of femininity, romance, Parisian life, fashion, and occasionally, mythology or allegory, all treated with his signature blend of elegance and charm.

Among his most celebrated works is Leda and the Swan (1934), a sensual reinterpretation of the classical myth, showcasing his ability to blend traditional subjects with modern aesthetics. The etching combines aquatint and drypoint, highlighting the graceful curves of Leda and the powerful form of the swan, rendered with characteristic fluidity. Another well-known piece, Symphony in Blue (1936), depicts an elegant woman reclining on a chaise lounge, enveloped in luxurious blue fabrics, embodying the sophisticated languor often found in his work.

His illustrations for books, such as La Dame aux Camélias, demonstrate his skill in narrative and his sensitivity to literary themes, translated into visual form. Works like Après-midi d'été capture the leisurely atmosphere of Parisian society, while pieces featuring animals, like the playful Little Butterflies or images with sleek greyhounds, add a touch of whimsy and dynamism. Eva (1928), a colour lithograph, presents a classic Icart beauty with direct yet alluring gaze.

Even later works, such as the series La Vie des Seins (The Life of Breasts) from 1945, which included etchings like Apple Breasts, continued his exploration of the female form, albeit with a more focused, almost clinical yet still aestheticized approach. Pieces like Sofa (c. 1930s) or On the Green encapsulate the leisure and luxury associated with the era. The recurring motif of the sophisticated, self-aware woman, navigating the modern world with grace and allure, remains the central, unifying theme across his diverse body of work. These images captured the aspirations and fantasies of a generation, solidifying Icart's reputation.

International Acclaim and Commercial Success

Louis Icart's art resonated deeply not only with French audiences but also internationally, particularly in the United States. During the 1920s and 1930s, his etchings became highly fashionable, decorating the homes of affluent collectors and admirers of the Art Deco style. His success was partly due to his keen understanding of the market and his ability to produce high-quality, desirable prints in editions that made them accessible, yet still exclusive.

His American popularity was significant. The dual-edition strategy—producing slightly different versions or editions specifically for the US market—proved highly effective. American audiences embraced his depictions of glamour, romance, and Parisian chic, themes that aligned perfectly with the optimistic, albeit sometimes hedonistic, spirit of the Roaring Twenties and the escapist desires of the Depression era that followed. His works were exhibited in major American galleries, and publications featured his art, further cementing his reputation overseas.

Beyond fine art prints, Icart's distinctive style lent itself well to commercial applications. His illustrations appeared in fashion magazines, on advertising materials, and as book illustrations, bringing his aesthetic to an even wider audience. This commercial success, while sometimes viewed critically by the fine art establishment, was instrumental in making him a household name and a defining visual artist of his time. His ability to bridge the gap between fine art and popular illustration contributed significantly to the pervasiveness of the Art Deco aesthetic in everyday life. His works were collected by individuals and institutions, including major museums like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, acknowledging his artistic merit and cultural significance.

Art Historical Significance and Legacy

Louis Icart occupies a distinct and important place in 20th-century art history, primarily as a leading figure of the Art Deco movement. While perhaps not as revolutionary as the Cubists or Surrealists who were his contemporaries, Icart masterfully captured and defined the visual sensibility of a specific era. His work serves as a vibrant chronicle of the tastes, fashions, and social mores of Paris and New York between the wars.

His significance lies in his unique synthesis of historical influences and modern style. By adapting the grace and charm of 18th-century French art (Watteau, Boucher, Fragonard) to the context of the 20th century, and infusing it with hints of Impressionist light (Monet, Renoir) and Symbolist mood (Redon, Moreau, perhaps even Klimt in its decorative sensuality), he created an aesthetic that was both nostalgic and thoroughly modern. His fluid line work, often compared to that of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec in its expressiveness though generally lighter in tone, defined the idealised female form for a generation.

Icart's influence can be seen in the broader field of illustration and decorative arts of the period. His particular vision of feminine glamour resonated widely and contributed to the overall Art Deco look. While some critics might dismiss his work as overly decorative or commercially oriented, its enduring popularity and technical brilliance cannot be denied. He excelled in the demanding medium of colour etching, producing works of exceptional quality and detail.

His legacy endures through his artworks, which remain highly sought after by collectors, and through his contribution to the visual identity of the Art Deco era. He provided a counterpoint to the more austere or abstract tendencies in modern art, championing elegance, beauty, and a certain joie de vivre that continues to appeal. His art offers a captivating glimpse into a bygone world of sophistication and charm, securing his status as a master of his chosen style and time.

The Collector's Market: Auctions and Authenticity

Today, Louis Icart's works remain highly popular in the art market, particularly his etchings. Auction houses regularly feature his prints, and prices can vary significantly depending on several factors, including the rarity of the image, the condition of the print, the quality of the impression and hand-colouring, the presence of the artist's signature (typically in pencil), and the specific edition (European vs. American, or numbered editions).

Auction results show a wide range. Common prints in average condition might sell for a few hundred dollars or euros, as seen with estimates for works like Eva (€300-€400) or Leda and the Swan (€900-€1200) in certain sales. However, rarer or particularly desirable images in excellent condition can command much higher prices, sometimes reaching tens of thousands of dollars or pounds. For instance, Hunting II fetched £19,000 at a Sotheby's auction. Japanese auctions also see activity, with works like Don Juan or Bell Rose estimated in the ¥40,000-¥80,000 range. Works like Le Panier de pommes (The Basket of Apples), noted as a rare original print from 1928, are particularly valued.

The market for Icart's work experienced a significant boom in the late 1980s, and while current prices may not consistently reach those peaks, demand remains steady. His prints are also traded through galleries and online platforms like eBay, where prices can range dramatically.

Prospective collectors need to be mindful of authenticity. Genuine Icart etchings typically bear specific characteristics. Most original etchings feature an embossed seal or blind stamp, often near the plate mark, which might read "Copyright [Year] by L. Icart Sty., Paris" or include a windmill motif associated with his Montmartre studio ("Moulin de la Galette"). The artist's pencil signature is usually found just below the image on the right. Dimensions should also conform to recorded sizes for specific prints. Reproductions and later restrikes exist, so careful examination and provenance research are advisable when acquiring his work.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Elegance

Louis Icart's artistic journey took him from the fashion houses of Toulouse and Paris to the battlefields of World War I and ultimately to international renown as a master of Art Deco elegance. His distinctive style, characterized by fluid lines, delicate colours, and a focus on the alluring modern woman, captured the spirit of his age with remarkable charm and technical skill. Through his prolific output of etchings, paintings, and illustrations, he created a world of sophistication, romance, and subtle sensuality that continues to captivate audiences today.

While deeply rooted in the aesthetics of the 1920s and 1930s, Icart's work transcends mere period decoration. His mastery of etching techniques, his ability to synthesize historical influences with contemporary sensibilities, and his creation of iconic feminine imagery secure his position as a significant artist of the early 20th century. His enduring popularity in the art market attests to the timeless appeal of his vision. Louis Icart remains celebrated not just as a chronicler of Art Deco glamour, but as an artist who dedicated his life to the pursuit and portrayal of beauty.