Richard Dighton (1795-1880) stands as a notable figure in the annals of British art, particularly celebrated for his insightful and often humorous satirical prints and portraits. Flourishing during a period of significant social and cultural transition in Britain, Dighton's work provides a fascinating visual commentary on the personalities and mores of his time. His art, bridging the gap between the robust caricature tradition of the late 18th century and the more refined society portraits of the Victorian era, offers a unique window into the world he inhabited. As the son of the equally renowned caricaturist Robert Dighton, Richard inherited a keen observational skill and a talent for capturing the essence of his subjects, contributing significantly to the rich tapestry of British graphic art.

Early Life and Artistic Inheritance

Born in London in 1795, Richard Dighton was immersed in the world of art from a young age. His father, Robert Dighton (c. 1752–1814), was a well-established artist, actor, and print-seller, known for his own popular series of satirical portraits and genre scenes. This familial environment undoubtedly shaped Richard's artistic inclinations. He would have learned the rudiments of drawing, etching, and watercolor painting under his father's tutelage, absorbing the techniques and stylistic nuances that characterized the Dighton family's artistic output. The elder Dighton's studio was a hub of activity, producing prints that were widely circulated and enjoyed for their wit and topicality. This exposure to the commercial side of art, as well as the creative process, provided Richard with a practical understanding of the art market and public taste.

The late 18th and early 19th centuries were a golden age for British caricature, with artists like James Gillray, Thomas Rowlandson, and Isaac Cruikshank producing powerful and often savage visual satires on political and social life. While Robert Dighton's work was generally gentler in tone than that of these contemporaries, he was a master of the character study, a trait Richard would develop further. Richard's early works often bear a resemblance to his father's style, focusing on single figures or small groups, rendered with a clear line and often enhanced with delicate watercolor washes. He quickly developed his own distinct voice, however, one that combined acute observation with a subtle, less overtly aggressive humor.

The Rise of a Caricaturist and Portraitist

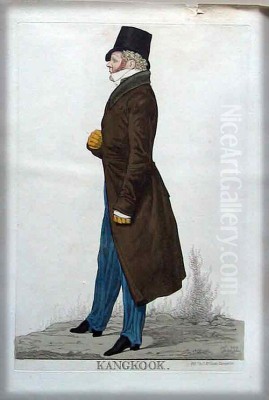

Richard Dighton's independent career began to flourish in the 1810s and 1820s. He initially established himself in London, the vibrant epicenter of British society and culture. His primary medium for caricature was the etched print, often hand-colored, which allowed for relatively wide dissemination. These prints typically featured full-length or bust portraits of well-known public figures – politicians, military men, aristocrats, clergymen, dandies, and city characters. His subjects were often depicted in characteristic poses, their individual quirks and vanities subtly highlighted. Unlike the more politically charged work of Gillray, Dighton's satire was generally more personal and social, focusing on the foibles and affectations of individuals rather than broad political commentary.

His series of "City Characters" and "London Nuisances" captured the everyday life and notable personalities of the metropolis. These works demonstrate his keen eye for detail and his ability to encapsulate a personality with a few deft strokes. He was adept at portraying the fashionable elite, such as the dandies who frequented St. James's Street, capturing their studied elegance and sometimes their absurd pretensions. One of his most famous subjects from this period was George "Beau" Brummell, the arbiter of men's fashion, whom Dighton depicted with an air of cool detachment.

Around 1828, Dighton relocated from London to Cheltenham, a fashionable spa town in Gloucestershire. This move marked a slight shift in his artistic focus. While he continued to produce satirical prints, he also increasingly concentrated on portraiture, particularly watercolor portraits. Cheltenham, with its influx of wealthy visitors seeking health cures and social amusement, provided a ready market for portrait artists. Dighton advertised his services, and his reputation as a skilled likeness-taker grew. His Cheltenham portraits, often full-length watercolors, are characterized by their delicate execution, pleasing color palettes, and an ability to convey the sitter's social standing and personality. He also began to explore lithography more extensively during this period, a newer printmaking technique that offered different textural possibilities.

Notable Works and Subjects

Richard Dighton's oeuvre is extensive, comprising hundreds of individual prints and drawings. Among his most recognizable and representative works are his satirical portraits of prominent figures.

His early etchings, such as A Lawyer & his Client, A Hero of the Turf & his Agent, and A Master Parson & his Journeyman (all dating from the period 1801-1812, though some sources suggest these might be by his father or collaborative, given Richard's youth), exemplify the Dighton style of character study, often with a narrative or anecdotal quality. These works, if indeed by the younger Richard or heavily influenced by his father, show an early grasp of social observation.

A particularly well-known caricature is Devonshire To Wit (1822), a depiction of William George Spencer Cavendish, the 6th Duke of Devonshire. This print captures the Duke, a prominent Whig politician and socialite, with a characteristic Dightonesque blend of respect and gentle mockery. The title itself, a pun on legal terminology, adds to the wit. Such works were popular precisely because they offered recognizable, yet slightly exaggerated, likenesses of public figures, making them a form of visual gossip and social commentary.

His portraiture also includes more formal, though still characterful, depictions. The portrait of Edward Gostwyck Cory (1840) showcases his skill in watercolor, capturing the subject with a sense of quiet dignity. Later in his career, he produced works like the equestrian portrait of Henry Elwes (1879-1880), demonstrating his continued activity and versatility even in his advanced years. This particular piece highlights his ability to render not just human figures but also animals with accuracy and spirit. Another work, titled Smiths Dorian Mr. 841 (1841), with its intriguing title and depiction of animals, cloaks, and hats, suggests a broader range of subject matter, perhaps touching on sporting life or specific social types associated with certain attire or activities.

Dighton's subjects were drawn from a wide cross-section of society. He depicted leading statesmen like the Duke of Wellington and Lord Castlereagh, legal figures, military officers, university dons, actors like Edmund Kean, and even notorious figures. His series of Oxford and Cambridge dons, for instance, are particularly valued for their portrayal of academic life in the early 19th century. Each figure is individualized, their academic gowns and peculiar postures rendered with an eye for the characteristic.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Richard Dighton's artistic style is characterized by its clarity, economy of line, and subtle humor. In his caricatures, he generally avoided the grotesque exaggerations favored by some of his contemporaries like George Cruikshank in his more fantastical moments. Instead, Dighton's satire relied on a more nuanced approach, emphasizing posture, costume, and facial expression to convey character. His figures are typically presented in profile or three-quarter view, often standing alone against a plain background, which focuses attention entirely on the subject.

His primary printmaking technique was etching, often combined with aquatint to create tonal variations. The etched lines are clean and precise, defining form with confidence. Many of his prints were hand-colored with watercolors, a task that might have been carried out in his studio by assistants, or by himself for special commissions. The coloring is generally delicate and harmonious, adding to the visual appeal of the prints without overwhelming the linear quality of the design. The use of watercolor was a natural extension of his drawing practice, and he was highly proficient in this medium, as evidenced by his standalone watercolor portraits.

In his watercolor portraits, Dighton demonstrated a fine sense of observation and a delicate touch. These works are often more naturalistic than his satirical prints, though they still retain a strong sense of character. He paid careful attention to details of costume and accessories, which helped to define the sitter's social status and personality. His palette was typically bright and clean, and his handling of the medium was fluid and assured. These portraits were often full-length, allowing him to capture the entire figure and their fashionable attire, much like the work of contemporary society portraitists such as Sir Thomas Lawrence, though Dighton's were generally on a smaller, more intimate scale and in a different medium.

Later in his career, Dighton also embraced lithography. This planographic printing process, invented in the late 18th century by Alois Senefelder, allowed for a more direct drawing style, akin to drawing on paper with a greasy crayon. Lithography offered a softer, more tonal quality than etching, and Dighton utilized it for some of his later portraits and character studies. His adaptability across these different media—etching, watercolor, and lithography—speaks to his technical versatility. He was also a publisher of his own prints, managing their production and distribution, a common practice for artists of his era, including Thomas Bewick, the master wood engraver, who also managed his own workshop.

The Dighton Dynasty and Legacy

Richard Dighton was part of an artistic family that spanned several generations. His father, Robert, established the family's reputation in the field of caricature and portraiture. Richard, in turn, built upon this foundation, adapting his style to the changing tastes of the Regency and early Victorian periods. The Dighton artistic tradition did not end with Richard. His own son, Richard Dighton Jr. (c. 1824–c. 1891), also became an artist, initially working in a similar vein to his father, producing portraits and character studies. Later, Richard Jr. embraced the new medium of photography, establishing himself as a photographer in Cheltenham and Worcester, thus continuing the family's engagement with visual representation, albeit through a modern technological lens.

Richard Dighton's influence can be seen in the development of British caricature and illustration. His style of single-figure caricatures, often accompanied by witty captions or titles, provided a model for later artists. The popular society caricatures published in magazines like Vanity Fair from the 1860s onwards, particularly the work of artists such as "Spy" (Leslie Ward) and "Ape" (Carlo Pellegrini), owe a debt to the tradition established by the Dightons and their contemporaries. These later caricaturists adopted a similar format of full-length, subtly exaggerated portraits of public figures, though often with a greater degree of sophistication in printing techniques, such as chromolithography.

His work is also valued by social historians for the vivid picture it provides of British society during his lifetime. His prints document the fashions, manners, and personalities of the era with an accuracy and immediacy that is often lacking in more formal historical records. From the dandies of London to the academics of Oxford and the visitors to Cheltenham Spa, Dighton's art captures a diverse range of social types and environments. His depictions of military figures, for example, provide a visual record of the men who served during the Napoleonic Wars and beyond, complementing the grander history paintings of artists like Benjamin West or the battle scenes of Denis Dighton (Richard's brother, a specialist military painter).

The enduring appeal of Richard Dighton's work lies in its combination of artistic skill, gentle humor, and historical interest. His prints are still collected today and can be found in major museums and galleries, including the British Museum and the National Portrait Gallery in London. They offer a charming and insightful glimpse into a bygone era, rendered by an artist who was both a keen observer and a skilled craftsman. His ability to capture the essence of an individual with wit and elegance ensures his place among the notable British artists of the 19th century, alongside contemporaries who explored different facets of portraiture and social commentary, from the refined society portraits of Sir Martin Archer Shee to the more narrative and illustrative work of artists like Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne), who famously illustrated Dickens.

Anecdotes and Personal Life

While much of Richard Dighton's life was dedicated to his art, a few details and anecdotes offer glimpses into his personality and experiences. His move from the bustling metropolis of London to the more genteel spa town of Cheltenham in 1828 suggests a desire for a different pace of life or a strategic career move to tap into a new clientele. In Cheltenham, he was not just an artist but also a respected member of the community. His advertisements in local newspapers attest to his entrepreneurial spirit.

An interesting familial connection is that Richard Dighton was the father of John Elwes Dighton (who later took the surname Fountaine), a notable figure in his own right, though not as an artist. John Elwes was reportedly a keen botanist and entomologist, with a particular passion for agriculture, described by some as being "mad about farming." This divergence in interests within the family highlights the varied paths taken by different generations.

One of the more curious, and perhaps apocryphal, stories surrounding Richard Dighton concerns his death. While he died in London on April 13, 1880, some sources from the period, or slightly later romanticized accounts, allude to a more exotic demise, with one rather poetic but unsubstantiated claim suggesting he died in India. The description of his supposed end – "a breath of the jungle in a puff of wind, a stumble in a step, a poison in a cup of water" – sounds more like a literary invention than a factual account. Standard biographical records confirm his death in London. Such embellishments, however, sometimes attach themselves to well-known figures, adding a layer of mystique.

His long life spanned a period of immense change in Britain, from the Napoleonic Wars through the Industrial Revolution and into the high Victorian era. He witnessed shifts in artistic taste, the rise of new technologies like photography (which his son adopted), and the transformation of British society. Throughout it all, he remained a dedicated artist, producing a consistent body of work that reflected the world around him. His contemporaries in the broader art world included landscape masters like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, who were revolutionizing their genre, and Pre-Raphaelite painters like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais, who emerged in the latter part of Dighton's career, signaling new directions in British art. Dighton, however, remained true to his own particular niche of portraiture and social caricature.

Conclusion: An Enduring Visual Chronicler

Richard Dighton's contribution to British art is significant, particularly within the realm of caricature and portraiture. He successfully navigated the transition from the robust, often politically charged satire of the late Georgian period to the more character-focused and socially observant art of the early Victorian era. His keen eye, deft hand, and subtle wit allowed him to create a vast gallery of portraits that bring the personalities of his time to life. From the famous to the merely fashionable, his subjects are rendered with an individuality that makes them more than just historical types; they emerge as believable, if sometimes amusing, human beings.

His work serves as an invaluable historical document, offering insights into the social fabric, fashions, and notable figures of Regency and early Victorian Britain. As an artist who inherited a family tradition and adapted it to his own talents and the changing times, Richard Dighton carved out a distinct and enduring place for himself. His prints and watercolors continue to be appreciated for their artistic merit, their humor, and the window they provide onto a fascinating period of British history. He stands as a testament to the power of graphic art to capture the spirit of an age, his legacy preserved in the many faces he so skillfully and memorably depicted, ensuring his relevance alongside other chroniclers of society, whether they be the literary observations of Jane Austen or the journalistic sketches of William Makepeace Thackeray.