Louis Robert Carrier-Belleuse, a name perhaps less instantly recognizable than some of his contemporaries, nonetheless carved a significant niche for himself in the vibrant and transformative art world of 19th-century France. A painter, sculptor, and ceramicist of considerable talent, he navigated the shifting artistic currents of his time, leaving behind a body of work that reflects both the academic traditions he was schooled in and a keen observation of modern life, coupled with a profound understanding of the decorative arts. His legacy is intertwined with that of his famous father, his own diverse creations, and his contributions to one of France's most prestigious artistic institutions.

An Artistic Lineage and Formative Years

Born in Paris on July 4, 1848, Louis Robert Carrier-Belleuse was immersed in art from his earliest days. He was the son of the highly acclaimed and prolific sculptor Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse (1824-1887), a dominant figure in Second Empire sculpture, known for his sensuous figures, decorative exuberance, and mastery of materials ranging from marble to terracotta and bronze. Albert-Ernest's studio was a hub of activity, and his influence on the decorative arts, including his tenure as artistic director at the Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory, was profound. Louis Robert's brother, Pierre Carrier-Belleuse (1851-1932), also pursued an artistic career, becoming a noted painter, particularly known for his elegant pastel portraits and scenes of dancers.

This familial environment undoubtedly shaped Louis Robert's artistic inclinations. He formally commenced his artistic education at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. There, he studied under influential academic painters Gustave Boulanger (1824-1888) and Alexandre Cabanel (1823-1889). Boulanger, known for his classical and Orientalist subjects, and Cabanel, a master of the academic style favored by the Salon and Napoleon III (his "Birth of Venus" was a sensation), instilled in him a strong foundation in drawing, composition, and the prevailing aesthetic ideals of the time. Alongside his painting studies, Louis Robert also honed his skills in a bronze workshop, learning the intricate techniques of engraving and metalwork, an experience that would prove invaluable in his later sculptural and decorative endeavors.

His artistic debut came at the Paris Salon of 1870, the official, juried art exhibition that was the primary venue for artists to gain recognition. The outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) interrupted his nascent career, as he, like many young Frenchmen, participated in the conflict. This period of national upheaval undoubtedly left its mark, and upon his return, he resumed his artistic pursuits with renewed vigor.

A Painter of Parisian Life and Genre

Initially, Louis Robert Carrier-Belleuse focused primarily on painting. His works from this period often depicted scenes of contemporary Parisian life, rendered with a realist sensibility that captured the nuances of different social strata. He was an astute observer of the urban environment, and his canvases often featured working-class figures, street scenes, and moments of everyday existence.

One of his early Salon entries, The Letter (1870), showcased his ability to convey narrative and emotion through carefully rendered details. Later paintings, such as Flour Carriers (Porteurs de farine, 1885) and Booksellers (Les Bouquinistes, 1881), are excellent examples of his engagement with social realism. These works provide a glimpse into the bustling, laborious, and intellectual life of the French capital. Flour Carriers, for instance, depicts the strenuous work of men hauling sacks of flour, their bodies conveying effort and resilience, set against an urban backdrop. Such scenes aligned with a broader trend in 19th-century art, where artists like Jean-François Millet or Gustave Courbet had earlier championed the depiction of rural and urban labor, though Carrier-Belleuse's approach was generally less overtly political and more focused on picturesque observation.

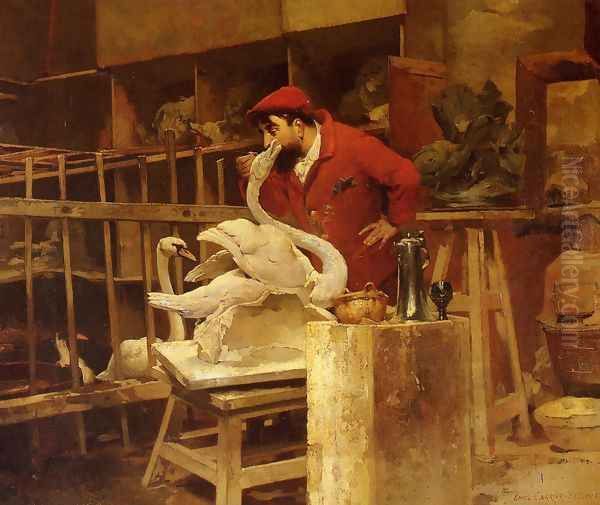

He also ventured into more anecdotal and sometimes humorous genre scenes. A work like The Animal Sculptor demonstrates this facet of his oeuvre, portraying a sculptor in his studio humorously interrupted by a live swan, a subject that perhaps reflects his own multifaceted artistic life and the challenges of capturing nature. His paintings were characterized by competent draughtsmanship, a muted but effective palette, and a clear, narrative style that appealed to the Salon juries and the art-buying public of the era. While not an Impressionist like Claude Monet or Edgar Degas, who were revolutionizing painting at the same time, Carrier-Belleuse's focus on modern life shared some common ground, albeit expressed through a more traditional visual language.

The Call of Three Dimensions: Sculpture

Given his father's towering reputation as a sculptor, it was perhaps inevitable that Louis Robert would also explore the medium of sculpture. He developed a distinct sculptural voice, though the influence of Albert-Ernest, particularly in the elegant modeling of figures and a certain decorative flair, can often be discerned. His sculptural output was diverse, ranging from portrait busts and statuettes to more ambitious public monuments.

His sculptural style often blended elements of Neo-Classicism, with its emphasis on idealized forms and clarity, and a Romantic sensibility that allowed for greater emotional expression and dynamism. He produced numerous smaller-scale sculptures, often in bronze or terracotta, which were popular with collectors. Works like Amazon Captive and Melodie exemplify his skill in rendering the human form, particularly the female figure, with grace and sensitivity. These pieces often carried allegorical or mythological themes, common in the academic tradition.

A significant aspect of his sculptural career involved commissions for public monuments, particularly in Central America. He designed a notable memorial statue for Juan Rodríguez Barrundia, a liberal reformer in Guatemala. This foray into international commissions highlights the reach of French artistic influence during this period. His public sculptures, like those of many contemporaries such as Jules Dalou or Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (a major influence on his father), aimed to commemorate historical figures or embody national ideals, requiring a blend of realism in portraiture and allegorical grandeur.

One of his most recognized sculptural groups, often associated with his ceramic work as well, is Every Man for Himself (Sauve qui peut). This dynamic composition, depicting Tuscan children in a state of alarm, attempting to escape some unseen danger, showcases his ability to capture movement and dramatic tension. The theme itself, while specific, speaks to a universal human experience of vulnerability and the instinct for survival.

Mastery in Clay: The Sèvres Years and Ceramic Innovation

A pivotal moment in Louis Robert Carrier-Belleuse's career came in 1877 when he was introduced to the world of ceramics by Théodore Deck (1823-1891). Deck was a highly innovative ceramicist, renowned for his revival of Iznik pottery techniques, his brilliant turquoise glazes (the "bleu de Deck"), and his elevation of ceramics to a high art form. This encounter proved transformative for Carrier-Belleuse.

He quickly embraced the medium, bringing his painterly eye for composition and his sculptor's understanding of form to ceramic design. His talents did not go unnoticed, and he eventually became the artistic director of the prestigious Manufacture Nationale de Sèvres, the state-owned porcelain factory. This was a role his father, Albert-Ernest, had also held with distinction, further cementing the family's connection to this venerable institution.

At Sèvres, Louis Robert was instrumental in designing new models and overseeing artistic production. He was particularly adept at the "pâte-sur-pâte" technique. This demanding process involves building up a design in relief by applying successive layers of liquid clay (slip) of a different color onto an unfired ceramic body. It requires immense skill and patience, as each layer must be carefully applied and allowed to partially dry before the next. The resulting effect is a delicate, cameo-like relief.

His ceramic works often featured figural compositions, intricate floral motifs, and classical or allegorical scenes. The aforementioned Sauve qui peut vase, now housed in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, is a prime example of his mastery in ceramics, translating the dynamism of the sculptural group into a decorative object of exceptional quality. Other notable Sèvres designs attributed to him include vases with themes such as Music, Hercules, and the charming Children and Butterflies (1898). These pieces combined technical virtuosity with a refined aesthetic sensibility, often reflecting the prevailing tastes for both classical revival and Art Nouveau-inflected naturalism.

His work at Sèvres contributed to the factory's continued reputation for excellence and innovation in a period when decorative arts were gaining increasing recognition. He was working in an environment that included other talented designers and technicians, all contributing to the rich legacy of French ceramics. His efforts helped bridge the gap between fine art and industrial art, a key concern of movements like the Arts and Crafts in Britain and, later, Art Nouveau across Europe, championed by artists like Émile Gallé in glass and ceramics or René Lalique in jewelry and glass.

Notable Works and Artistic Recognition

Throughout his career, Louis Robert Carrier-Belleuse produced a significant body of work across various media. Beyond those already mentioned, other key pieces further illustrate his artistic range:

In painting, his Salon submissions continued to explore Parisian life and genre scenes, often with a focus on specific trades or social types. These works, while not revolutionary in the vein of Impressionism, found favor for their craftsmanship and relatable subject matter.

In sculpture, the Torchère au tambourin (Torchère with Tambourine), also in the Musée d'Orsay, is a fine example of his decorative bronze work, combining a functional object with elegant figural sculpture. His bronze group A group of grape-picking putti showcases a lighter, more Rococo-revival charm, reminiscent of his father's style and the work of artists like Clodion from the 18th century.

His ceramic designs for Sèvres remain highly prized. The technical complexity of pieces like the Sauve qui peut vase, with its intricate pâte-sur-pâte decoration, underscores his dedication to craftsmanship. These works were often showcased at major international exhibitions, such as the Expositions Universelles held in Paris, which were crucial platforms for artists and manufacturers to display their latest achievements.

Carrier-Belleuse's contributions were recognized with several accolades. He received two honorable mentions and a third-class medal at the Salons, acknowledging his consistent quality. A significant honor was the silver medal he received at the Exposition Universelle of 1889 in Paris, an event famous for the unveiling of the Eiffel Tower and a major showcase of global art and industry. He was also made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour, one of France's highest civilian awards, recognizing his services to French art.

Artistic Style and Evolution: Navigating Traditions

Louis Robert Carrier-Belleuse's artistic style evolved throughout his career, reflecting his diverse training and the changing artistic landscape. His early paintings were rooted in the academic realism taught by Boulanger and Cabanel, focusing on clear narrative, detailed rendering, and traditional composition. He shared this grounding with many Salon painters of his generation, such as Jean-Léon Gérôme or William-Adolphe Bouguereau, though his subject matter often leaned more towards contemporary genre than historical or mythological epics.

His transition into sculpture saw him embrace the Neo-Classical and Romantic traditions that had shaped much of 19th-century French sculpture. There's an elegance and a concern for anatomical accuracy in his figures that speaks to a classical training, while the dynamism and emotional content of pieces like Sauve qui peut show a Romantic influence. His father's eclectic style, which often incorporated Rococo Revival elements, also left an imprint, particularly in the decorative aspects of his work.

In ceramics, his style was characterized by a sophisticated blend of figural representation and decorative motifs. Working at Sèvres, he was at the forefront of artistic porcelain production. His designs often featured classical figures, putti, and naturalistic elements, sometimes hinting at the emerging Art Nouveau style with their flowing lines and organic forms, though he generally remained more anchored in established decorative vocabularies. The pâte-sur-pâte technique allowed for a subtlety and refinement that suited his elegant compositions.

He was not an avant-garde artist in the mold of the Impressionists or Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh or Paul Gauguin. Instead, Carrier-Belleuse operated successfully within the established Salon system and the prestigious state manufactory, adapting traditional skills to contemporary themes and decorative applications. His versatility was a key characteristic, allowing him to move fluidly between painting, sculpture, and ceramics, a trait less common among artists who increasingly specialized in a single medium.

Contemporaries, Collaborations, and the Rodin Connection

Louis Robert Carrier-Belleuse's career unfolded during a period of immense artistic ferment in Paris. He was a contemporary of the Impressionists (Monet, Renoir, Degas, Pissarro), the Symbolists (Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon), and a new generation of sculptors who were challenging academic conventions.

His most significant artistic connections were, naturally, within his own family and professional circles. His father, Albert-Ernest, was a central figure. It was in Albert-Ernest's bustling studio that a young Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) worked as an assistant from roughly 1864 to 1870 and again briefly in Brussels. Rodin's early career was significantly shaped by his time with the elder Carrier-Belleuse, from whom he learned about modeling, decorative work, and the practicalities of running a successful studio. While Louis Robert was younger than Rodin, they would have been aware of each other through this familial and professional link.

Indeed, a point of contention reportedly arose between Louis Robert and Rodin. It is said that Louis Robert was critical of Rodin's groundbreaking sculpture L'Age d'airain (The Age of Bronze, 1876), which was so realistic that Rodin was controversially accused of having cast it directly from a live model (surmoulage). This anecdote, if true, highlights the differing artistic paths and perhaps temperaments of the artists – Rodin pushing the boundaries of sculptural realism and expression, while Carrier-Belleuse, though skilled, operated within more accepted norms. The elder Carrier-Belleuse, despite some professional disagreements, generally supported Rodin.

His collaboration with Théodore Deck was crucial for his development as a ceramicist. Deck's workshop was a center of innovation, and his mentorship provided Louis Robert with the technical knowledge and artistic inspiration to excel in this medium. At Sèvres, he would have worked alongside other skilled artists and craftsmen, contributing to a collective artistic endeavor. His teachers, Boulanger and Cabanel, connected him to the heart of the academic art establishment.

Controversies and Anecdotes

While not a figure known for major public scandals, Louis Robert Carrier-Belleuse's career did have its points of interest and minor controversies, typical of the competitive art world. The reported friction with Rodin over The Age of Bronze is one such anecdote, illustrating the tensions that could arise between artists with different visions, even those connected through mentorship.

His innovations in ceramics at Sèvres, while generally lauded, might have also sparked professional rivalries, as is common in highly competitive fields like luxury porcelain production. The pressure to create novel and appealing designs was constant.

The themes of some of his sculptural works, such as the monument for Juan Rodríguez Barrundia or any potential works depicting figures like the American expansionist William Walker (if such a commission existed and was executed by him, as some sources vaguely suggest for sculptors of the era dealing with Central American themes), could have touched upon sensitive political or colonial narratives of the time. However, detailed information on specific controversies surrounding such commissions for Louis Robert is scarce.

His artistic journey itself, moving from painting to sculpture and then significantly into ceramics, while demonstrating versatility, might have been viewed by some purists of the time as a diffusion of focus. However, the 19th century also saw a growing appreciation for the decorative arts and the "artist-craftsman," a role Carrier-Belleuse embodied.

The influence of his highly successful father, Albert-Ernest, was likely a double-edged sword. While it provided connections and an unparalleled artistic education, it also created a formidable shadow from which to emerge and establish his own distinct artistic identity.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Louis Robert Carrier-Belleuse passed away in Paris on June 14, 1913. He left behind a rich and varied artistic legacy that, while perhaps overshadowed by more revolutionary figures of his era, holds a significant place in the history of 19th-century French art.

His primary influence lies in his contributions to the decorative arts, particularly ceramics. His work at Sèvres, especially his mastery of the pâte-sur-pâte technique and his elegant designs, helped maintain the manufactory's prestige and contributed to the broader elevation of ceramic art. His pieces are sought after by collectors and are represented in major museum collections, including the Musée d'Orsay and the Petit Palais in Paris, and international institutions that specialize in decorative arts.

As a painter, his depictions of Parisian life offer valuable historical and social insights, capturing the city's atmosphere and its inhabitants with a skilled and observant eye. These works contribute to the rich tradition of 19th-century genre painting.

In sculpture, he continued the strong French tradition of figural work, producing pieces that were both aesthetically pleasing and technically accomplished. While his father's influence is undeniable, Louis Robert developed his own nuanced style. The connection to Rodin, primarily through his father's studio, also places his family at a pivotal point in the development of modern sculpture, even if Louis Robert himself did not follow Rodin's radical path.

His career exemplifies the path of a highly skilled artist who successfully navigated the established art institutions of his time – the École des Beaux-Arts, the Salon, and the Sèvres manufactory. He demonstrated that an artist could achieve distinction and contribute meaningfully across multiple media, bridging the often-perceived gap between the "fine" arts of painting and sculpture and the "decorative" art of ceramics.

Louis Robert Carrier-Belleuse's legacy is that of a versatile and dedicated artist who enriched the artistic landscape of his time. His commitment to craftsmanship, his keen observational skills, and his ability to adapt his talents to various forms of artistic expression ensure his continued appreciation by those who study the multifaceted art world of 19th-century France. His work serves as a reminder of the diverse talents that flourished alongside the more famous names, contributing to the richness and complexity of this pivotal period in art history.