Louise Ingram Rayner (1832–1924) stands as a significant figure in British art history, celebrated particularly for her intricate and evocative watercolour depictions of the streets and architecture of Victorian Britain. Working during a period of immense social and industrial change, Rayner carved a niche for herself with atmospheric scenes that captured the character and daily life of historic towns and cities, most notably Chester. Her work offers a valuable window into the past, rendered with remarkable technical skill and sensitivity.

An Artistic Heritage

Louise Rayner was born into an environment steeped in art. Her birthplace was Matlock Bath in Derbyshire, but her family moved frequently during her childhood. Her father, Samuel Rayner, was a noted watercolour artist himself, known for his architectural subjects, particularly interiors of churches and great houses. He exhibited widely, including at the Royal Academy and the Society of British Artists.

Louise's mother, Anne Manser Rayner (née Manser), was also an accomplished artist, working primarily in engraving, particularly on black marble from Ashford-in-the-Water. The artistic lineage extended further; Louise was one of six children, and remarkably, five of them pursued artistic careers. Her sisters Nancy, Margaret, Rose, and Frances, along with her brother Richard Manser Rayner, all became recognized artists in their own right, creating a truly exceptional artistic family dynamic within the Victorian era.

Formative Years and Influences

Growing up surrounded by artistic practice undoubtedly shaped Louise's path. Her initial artistic instruction came from her father, Samuel Rayner, whose expertise in architectural rendering likely provided a strong foundation. From the age of fifteen, her training became more formalized, though it seems she did not attend a major art school but rather learned through practice and association with established artists within her family's circle.

Among the prominent artists cited as influences or informal mentors were figures well-respected in the Victorian art world. These included George Cattermole, known for his historical genre scenes often featuring dramatic architectural backdrops; the acclaimed topographical and architectural painter David Roberts, famous for his views of the Near East and Europe; and Edmund Niemann, a prolific landscape painter. The artist Frank Stone was also part of this circle, further enriching the artistic environment in which Louise developed her skills.

Early Career and a Change of Medium

Louise Rayner's professional career began not with watercolour, but with oil painting. Her first work accepted for exhibition at the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts in London, shown in 1852, was an oil painting titled "The Interior of Haddon Chapel". This debut piece reflected her father's influence in its choice of an architectural interior subject. She exhibited another oil painting, "The Nave of St. David's Cathedral," the following year.

However, around 1860, Rayner made a decisive shift towards watercolour. This medium would become her primary mode of expression for the rest of her long and productive career, spanning over half a century. It was in watercolour that she found her true voice, developing the detailed, atmospheric style for which she is best known. This change allowed her to explore the textures and light effects of street scenes with remarkable nuance.

The Allure of Chester

While Louise Rayner painted many locations across Britain, she is inextricably linked with the city of Chester. From around 1869, Chester became a recurring and central subject in her work. The city's unique architectural heritage, particularly its medieval Rows (galleried walkways above street-level shops), half-timbered buildings, Roman walls, and historic landmarks, provided a wealth of inspiration.

Chester in the Victorian era was a bustling county town, a blend of ancient structures and contemporary life. Rayner was drawn to this juxtaposition, capturing not just the bricks and mortar but the human activity within these historic settings. Her detailed views documented the city's fabric at a time before significant modern redevelopment, preserving a visual record of its unique character. She lived in Chester for a period with her sister, immersing herself in the city's atmosphere.

Capturing Chester's Soul

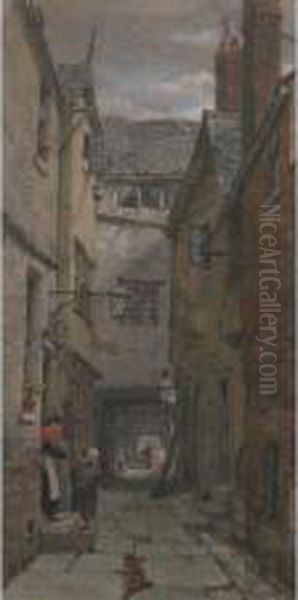

Rayner's Chester watercolours are celebrated for their meticulous observation. She depicted well-known streets like Watergate Street, Bridge Street, Eastgate Street, and Northgate Street, often focusing on the intricate facades of the Rows. Specific buildings frequently appear in her work, becoming iconic representations through her brush. These include the elaborately carved Bishop Lloyd's Palace, the historic God's Providence House, and venerable inns like the Bear and Billet.

She didn't just paint the grand vistas; Rayner also explored quieter corners, hidden alleyways, and atmospheric courtyards. Her compositions often lead the viewer's eye down a street or into a scene, inviting exploration. The inclusion of shop signs, hanging goods, architectural details, and the play of light and shadow all contribute to the immersive quality of her Chester views.

A Master of Detail and Texture

A hallmark of Louise Rayner's style is her extraordinary attention to detail and her ability to render texture convincingly in watercolour. She excelled at capturing the specific surfaces of the urban environment: the rough grain of ancient timber beams, the unevenness of cobblestone streets, the crumbling texture of old plasterwork, the weathered surfaces of stone, and even the ephemeral presence of faded posters on walls.

This focus on texture gives her work a tangible quality, making the scenes feel authentic and lived-in. She often employed techniques such as stippling, dry brush, and potentially the use of bodycolour (opaque watercolour or gouache) to achieve these effects, building up layers to create depth and richness. Her precision was remarkable, yet her works rarely feel stiff or merely photographic; they retain an artistic sensitivity.

Light, Atmosphere, and Daily Life

Rayner's paintings are not just architectural studies; they are imbued with atmosphere and populated by the people of the time. She often favoured compositions bathed in sunlight, casting strong shadows that define architectural forms and add drama to the scene. This use of light contributes to the often "picturesque" and inviting quality noted in her work.

Crucially, her street scenes are rarely empty. She included figures going about their daily business – shoppers browsing at market stalls, tradespeople at work, women chatting, children playing. These figures, though often small in scale, are essential elements. They animate the spaces, provide a sense of scale, and firmly place the scenes within the context of Victorian social life, offering glimpses into the era's activities and attire.

A Notable Work: The Phoenix Tower

Among her many Chester subjects, Rayner's depictions of the Phoenix Tower (also known as King Charles's Tower) on the city walls are particularly noteworthy. This location holds historical significance, as an inscription on the tower commemorates King Charles I watching the defeat of his troops at the Battle of Rowton Moor during the English Civil War in 1645.

Rayner painted the tower multiple times. Some depictions capture it bathed in her characteristic sunlight, while others, according to descriptions, possess a more sombre or atmospheric quality, perhaps reflecting the historical weight of the site. Her detailed approach would likely have included the textures of the old stone and potentially even alluded to the historical inscription, showcasing her ability to blend architectural accuracy with historical resonance.

Beyond Chester's Walls

Although Chester remained a favourite and defining subject, Louise Rayner's artistic explorations extended far beyond its walls. She travelled extensively throughout Britain during the summer months, sketching and gathering material for watercolours that she would often complete later. Her oeuvre includes views of numerous other historic towns and cities, demonstrating her broad interest in Britain's architectural heritage.

Locations featured in her work include Salisbury, with its magnificent cathedral close; the historic market towns of Ludlow and Shrewsbury in Shropshire; Leamington Spa in Warwickshire; her native Derby; and even scenes from Edinburgh in Scotland. This wider body of work reinforces her status as a topographical artist dedicated to documenting the picturesque and historic fabric of the nation.

Watercolour Technique Explored

Rayner's mastery of watercolour involved a combination of precise drawing and skilled application of paint. Her underlying drawing, likely done in pencil, provided the accurate framework for her detailed compositions. She used transparent washes to build up colour and tone, particularly for skies and larger areas, but her distinctive textural effects often relied on more complex techniques.

The use of bodycolour (gouache) for highlights, details on stonework or timber, and adding opacity seems probable in many works, allowing her to capture bright accents and solid forms effectively. Techniques like stippling (applying paint in small dots) and hatching or dry brush (using a brush with minimal moisture) were likely employed to render the varied textures of wood, stone, and plaster that are so characteristic of her style.

Exhibiting Across Britain

Louise Rayner maintained a consistent presence in the British art world through regular exhibitions over five decades. After her debut at the Royal Academy, she continued to exhibit there periodically. However, she found more frequent platforms elsewhere. She was a prolific contributor to the Society of Lady Artists (which later became the Society of Women Artists), exhibiting almost annually from the 1860s onwards.

She also showed her work at the Royal Watercolour Society (though she was not elected a member), the Society of British Artists (later the Royal Society of British Artists, RBA), the Dudley Gallery (a popular venue for watercolourists), the Liverpool Academy of Arts, Manchester Art Gallery, and the Royal Hibernian Academy in Dublin, among others. This extensive exhibition record underscores her professional commitment and the popularity of her work with the Victorian public.

A Professional Woman Artist

Achieving such a long and successful career as a professional artist was a significant accomplishment for a woman in the Victorian era. While the art world was gradually opening up, it remained largely male-dominated. Institutions like the Royal Academy were slow to admit women as full members. Societies specifically for women artists, like the Society of Lady Artists, provided crucial exhibition opportunities and professional networks.

Louise Rayner's dedication to her craft, her consistent output, and her ability to find a market for her detailed and appealing watercolours allowed her to support herself through her art, primarily living in Chester and later in St Leonards-on-Sea, Sussex, where she died in 1924. Her career serves as an example of female artistic professionalism in the 19th century.

Innovation in Dissemination

An interesting aspect of Rayner's practice, mentioned in some accounts, was her reported habit of taking photographs of her finished watercolours. The purpose was apparently to facilitate the creation and sale of prints based on her popular views. In an era before colour photography was viable and high-quality colour printing was complex and expensive, this suggests a practical and perhaps forward-thinking approach to reaching a wider audience and potentially generating additional income from her most successful images.

Victorian Contemporaries and Context

Louise Rayner worked during a vibrant period for British watercolour painting and genre scenes. Her detailed style and focus on picturesque architecture and daily life can be seen in relation to other artists of the era. Her father, Samuel Rayner, and mentors like David Roberts and George Cattermole provided direct links to established traditions of architectural and topographical art. Samuel Prout was another earlier master of detailed European architectural watercolours whose influence might be discerned.

Contemporaries exploring similar themes of rural or urban life, often with meticulous detail, included Myles Birket Foster, renowned for his idyllic country scenes, and Helen Allingham, celebrated for her charming depictions of cottages and gardens. William Henry Hunt was a master of highly detailed still life and rustic figures in watercolour. Albert Goodwin created atmospheric landscapes and city views, often with a more poetic sensibility. Even the Pre-Raphaelite circle, through artists like Ford Madox Brown (whose painting 'Work' is a complex Victorian urban scene), showed an interest in detailed observation of contemporary life, albeit with different aims. The influential critic and artist John Ruskin championed detailed observation of nature and architecture, shaping the era's aesthetic values.

Enduring Legacy

Louise Rayner's legacy rests primarily on her captivating and historically valuable watercolours of British towns, especially Chester. Her works are held in numerous public collections, including the Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum in Bournemouth, Derby Museum and Art Gallery (which holds a significant collection reflecting her local origins), and importantly, the Grosvenor Museum in Chester, which houses many of her iconic views of the city.

Her paintings continue to be admired for their technical skill, atmospheric charm, and detailed documentation of Victorian urban environments. The enduring interest in her work is demonstrated by initiatives like guided walks in Chester specifically following the locations she painted, allowing people to compare her views with the city today. She remains one of the most beloved visual chroniclers of historic Chester.

Final Reflections

Louise Ingram Rayner was more than just a painter of picturesque streets; she was a dedicated professional artist who developed a distinctive style perfectly suited to her chosen subject matter. Her watercolours offer a compelling blend of architectural accuracy, atmospheric effect, and social observation. Through her meticulous brushwork, she captured the unique character of Victorian towns and cities, preserving views of a Britain undergoing rapid change. Her works remain a source of delight for their artistic merit and serve as invaluable historical documents, securing her place as a significant figure in the rich tradition of British watercolour painting.