Thomas Hosmer Shepherd (1793-1864) stands as a significant figure in the realm of British topographical art, a diligent and skilled watercolourist whose work provides an invaluable visual record of London and other British cities during a period of profound transformation. His meticulous attention to architectural detail, combined with a keen eye for the bustling life of the streets, has ensured his enduring importance not only to art historians but also to social and urban historians. Shepherd's legacy is one of precision, charm, and an unwavering dedication to capturing the essence of the built environment.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis

Born in France on January 16, 1793, Thomas Hosmer Shepherd's early life saw a relocation with his family to England, where they eventually settled in the environs of London. This move placed the young Shepherd at the heart of a rapidly expanding and evolving metropolis, an environment that would become the primary subject and inspiration for much of his artistic career. The exact details of his artistic training are not extensively documented, but it is clear that he developed a remarkable proficiency in watercolour, a medium perfectly suited to the detailed and often delicate renderings required for topographical illustration.

His career is generally considered to have spanned from approximately 1809 to 1859. This period witnessed significant architectural development and urban renewal in Britain, particularly in London. Shepherd emerged as an artist at a time when there was a growing public appetite for images of familiar landmarks, new developments, and picturesque street scenes. This demand was fueled by an increasing sense of national pride, a burgeoning tourist trade (both domestic and international), and the proliferation of illustrated books and periodicals.

The Pivotal Patronage of Frederick Crace

A defining relationship in Shepherd's professional life was his long-standing association with Frederick Crace (1779-1859). Crace was a prominent interior designer, a passionate collector of maps and prints related to London, and a key figure in the documentation of the city's architectural heritage. Recognizing Shepherd's talent for accurate and aesthetically pleasing architectural depiction, Crace commissioned him extensively to create watercolours of London's buildings and notable locations.

These commissions, undertaken over several decades, formed a substantial part of the renowned Crace Collection, now housed primarily in the British Museum. This collection is a treasure trove of London topography, and Shepherd's contributions are central to its value. Crace's patronage not only provided Shepherd with consistent employment but also helped to establish his reputation as a leading topographical artist. The works created for Crace were often intended as historical records, capturing buildings that were soon to be demolished or significantly altered, as well as newly erected structures that signified London's progress.

A Master of Metropolitan Depiction: London in Watercolour

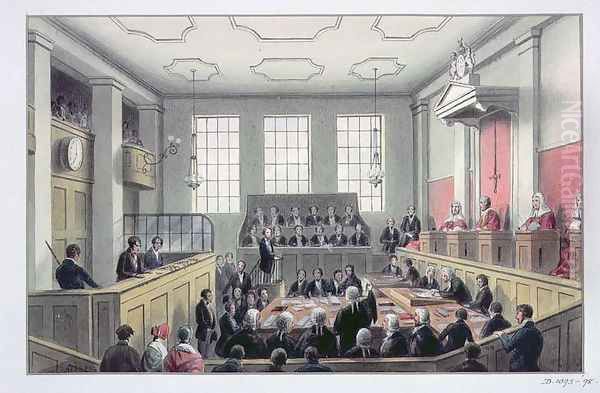

London was undoubtedly Thomas Hosmer Shepherd's principal muse. He possessed an intimate knowledge of the city's streets, squares, and landmarks, from its grandest public buildings to its more humble commercial and residential areas. His watercolours are characterized by their clarity, their precise rendering of architectural features, and their ability to convey the specific atmosphere of a location. He did not merely draw buildings; he situated them within their urban context, often including figures, carriages, and street vendors that brought the scenes to life.

His depictions of _The Bank of England_ showcase his ability to handle complex classical architecture, capturing its imposing grandeur. Similarly, his views of _The London University_ (now University College London) document an important new institution and its architectural embodiment. Shepherd's work was instrumental in popularizing and disseminating images of these and countless other London sites.

Many of Shepherd's London views were created with an eye towards publication. The early 19th century saw a boom in illustrated books, and steel engraving allowed for the relatively inexpensive mass reproduction of images. Shepherd's detailed watercolours were ideal for translation into this medium.

Key Publications and the Dissemination of Shepherd's Vision

One of the most significant publications featuring Shepherd's work was _Metropolitan Improvements; or London in the Nineteenth Century_ (1827-1830), published by Jones & Co. and written by the architect James Elmes. This series showcased the recent architectural developments in London, including the grand schemes of John Nash, such as Regent Street and Regent's Park. Shepherd's illustrations for this work provided the public with vivid images of these ambitious urban projects, celebrating London's status as a modern, dynamic capital. His views captured the elegance of new terraces, the formality of public squares, and the innovative designs of public buildings.

He also contributed regularly to the _Illustrated London News_, one of the pioneering illustrated periodicals that brought visual news to a wide audience. His topographical and architectural illustrations would have been a familiar sight to its readers. Despite this consistent output, it is noted that Shepherd experienced periods of financial hardship, particularly after 1842, a common plight for many artists reliant on commissions and the vagaries of the art market.

Shepherd's work also appeared in Rudolph Ackermann's _Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics_. Ackermann was a hugely influential publisher and print seller, and his Repository was a leading periodical that featured high-quality coloured aquatints. Artists like Augustus Pugin (Augustus Charles Pugin, father of the more famous A.W.N. Pugin) also contributed significantly to Ackermann's publications, often depicting similar architectural and urban scenes.

Beyond the Capital: Documenting Other British Cities

While London was his primary focus, Shepherd's talents were also applied to other important British cities. He produced illustrations of Edinburgh, often referred to as "The Modern Athens" due to its neoclassical architecture and intellectual vibrancy. His work for a publication titled _Modern Athens! Displayed in a Series of Views: or Edinburgh in the Nineteenth Century_ (1829), also with text by James Elmes (though often attributed to John Britton), captured the unique character of the Scottish capital, from the Old Town's historic Royal Mile to the New Town's elegant Georgian squares.

He also documented the architectural landscapes of Bath and Bristol, cities renowned for their distinctive Georgian architecture and historical significance. These works, often published in series like _Bath and Bristol, with the Counties of Somerset and Gloucester, Displayed in a Series of Views_ (c. 1829-1831), further demonstrate his ability to adapt his meticulous style to different urban environments, capturing their unique topographies and architectural vernaculars.

Artistic Style, Technique, and Characteristics

Thomas Hosmer Shepherd's artistic style is firmly rooted in the British topographical tradition. His primary medium was watercolour, often with pen and ink to delineate architectural details with precision. His palette was generally clear and bright, lending a sense of vibrancy to his scenes. While accuracy was paramount, his works are far from being sterile architectural renderings.

A key characteristic of Shepherd's art is his attention to detail. Every window, column, and decorative element is carefully observed and rendered. This meticulousness is what makes his work so valuable as historical documents. He often worked from plein air sketches, capturing the immediate impression of a scene, which would then be worked up into a finished watercolour in the studio.

Shepherd had a talent for enlivening his compositions with human activity. His streets are rarely empty; they are populated with figures going about their daily business – ladies and gentlemen strolling, merchants selling their wares, carriages passing by, and children playing. These figures not only add visual interest and a sense of scale but also provide a glimpse into the social fabric of the time. His depictions of the newly opened London Zoo, for instance, such as _The Music Lawn_, _The Camel House Clock Tower_, _The Carnivora Terrace_, and _The Polar Bear Cage_, are charming examples of how he integrated human and animal life into his compositions, capturing the novelty and excitement of such public attractions.

His use of light and shadow was generally subtle, aimed at defining form and creating a sense of depth rather than dramatic effect. The overall impression is one of clarity, order, and a certain picturesque charm, even when depicting the grandest of structures. He captured the changing face of cities, from established landmarks like _Westminster Abbey_ or _St. Giles’ Cripplegate_ to newer constructions and even scenes of social concern, such as his view of the _Asylum for the Indigent Blind, Westminster, London_. Other specific works like _Montagu House_, the _Vine Inn, City of London_, an etching of _Regent's Park Lake_ (1830), and views of _Finsbury Park_ further illustrate the breadth of his London subjects.

The Shepherd Artistic Family

The tradition of topographical art was continued within the Shepherd family. Thomas Hosmer Shepherd's brother, George Sidney Shepherd (c. 1784–1862), was also a notable watercolourist who specialized in similar subjects. The brothers sometimes collaborated, and their styles can be quite similar, occasionally leading to confusion in attribution. George Sidney Shepherd was a founding member of the New Society of Painters in Water Colours (later the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours) in 1831, indicating his standing in the artistic community.

Furthermore, Thomas Hosmer Shepherd's sons, Frederick Napoleon Shepherd (born c. 1819) and Valentine Claude Shepherd, also followed in the family tradition of topographical drawing. The naming of his first son, Frederick Napoleon, is thought to commemorate a visit Thomas made to France in 1818, possibly during his honeymoon. This continuation of artistic practice across generations underscores the importance of family workshops and inherited skills in the art world of the 19th century.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Thomas Hosmer Shepherd worked within a vibrant artistic milieu, alongside many other artists engaged in topographical and architectural illustration. The demand for such work was high, driven by publishers, private collectors, and a public eager for images of their nation's cities and landscapes.

Besides his brother George Sidney Shepherd and collaborator Augustus Pugin, other notable figures in this field included:

Thomas Malton Jr. (1748-1804): Though slightly earlier, Malton's influential book A Picturesque Tour through the Cities of London and Westminster (1792-1801) set a high standard for architectural accuracy and picturesque urban views, likely influencing Shepherd.

Samuel Prout (1783-1852): Known for his picturesque depictions of European and British architecture, Prout had a distinctive, slightly more romanticized style but shared Shepherd's interest in architectural detail.

David Roberts (1796-1864): While famous for his views of the Near East, Roberts also produced many fine topographical works of British and European cities, often on a grander scale than Shepherd.

J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) and Thomas Girtin (1775-1802): These titans of British watercolour, while evolving in more expressive and atmospheric directions, both began their careers with detailed topographical work. Girtin, in particular, was a master of architectural subjects.

John Sell Cotman (1782-1842): A leading figure of the Norwich School, Cotman produced exquisite architectural drawings and watercolours, known for their elegant simplification of form and pattern.

Peter De Wint (1784-1849): Primarily a landscape painter, De Wint also produced notable architectural views, particularly of cathedrals, with a broad and fluid watercolour technique.

William Westall (1781-1850): An accomplished topographical artist who travelled widely, including with Matthew Flinders' expedition to Australia. He produced numerous views of British scenery and architecture for publications.

William Walter Burgess (fl. 1809-1840s): An engraver and artist who collaborated with Shepherd on publications like Londina Illustrata.

William Monk (1863-1937): Though later, Monk continued the tradition of depicting London, and his sketches appeared alongside Shepherd's in some compilations, indicating the enduring appeal of Shepherd's work.

John Britton (1771-1857): An influential antiquary and topographer whose numerous publications, such as The Architectural Antiquities of Great Britain and Cathedral Antiquities of England, employed many draughtsmen and engravers to document the nation's architectural heritage. Shepherd's work aligns closely with the aims of Britton's projects.

Edward Dayes (1763-1804): A watercolourist and engraver who taught Girtin and influenced Turner, Dayes produced many topographical views of Britain.

Paul Sandby (1731-1809): Often called the "father of English watercolour," Sandby was a key figure in establishing topographical watercolour as a respected art form. His work would have been foundational for artists of Shepherd's generation.

This network of artists, engravers, writers (like James Elmes), and publishers (like Rudolph Ackermann and Jones & Co.) created a rich ecosystem for the production and consumption of topographical art. Shepherd was a vital part of this system, his skill and reliability making him a sought-after illustrator.

Anecdotal Glimpses and Personal Life

While much of the focus on Shepherd is on his prolific output, a few personal details offer a more rounded picture. His sketching tour in 1810 indicates an early commitment to observing and recording the world around him directly. The aforementioned trip to France in 1818, possibly a honeymoon, and the subsequent naming of his son Frederick Napoleon Shepherd, provide a rare personal touch.

The fact that he faced financial difficulties later in his career, despite his consistent work for publications like the Illustrated London News, highlights the precarious nature of an artist's life in the 19th century, even for those with established reputations. It underscores the reliance on the fluctuating demands of patrons and publishers.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Thomas Hosmer Shepherd's primary legacy lies in the vast and detailed visual archive he created of Georgian and early Victorian Britain. His watercolours are more than just aesthetically pleasing pictures; they are invaluable historical documents. They allow us to see London and other cities as they were, to trace their development, and to understand the architectural fashions and urban planning ideals of the era.

His work is prized by collectors and institutions for its accuracy and charm. Major collections, including those at the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and various local archives like the Kensington and Chelsea Libraries, hold significant numbers of his watercolours. These collections are frequently consulted by researchers studying architectural history, urban development, and social history.

In the broader context of British art history, Shepherd is recognized as one of the most accomplished and prolific topographical artists of his generation. While he may not have sought the sublime or the overtly romantic in the manner of some of his contemporaries like Turner, his dedication to the faithful representation of the built environment carved out a distinct and important niche. He captured the "spirit of place" with an unassuming honesty that continues to resonate. His influence can be seen in the continuing tradition of architectural illustration and in the appreciation for urban sketching that persists today.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Thomas Hosmer Shepherd passed away in 1864, leaving behind an extraordinary body of work that continues to inform and delight. His watercolours offer a window onto a bygone era, capturing the architectural character and urban vitality of 19th-century Britain with a precision and artistry that few could match. As a meticulous chronicler of his times, Shepherd ensured that the streets, buildings, and daily life of cities like London, Edinburgh, and Bath would be preserved for future generations, securing his place as a key figure in the history of British topographical art. His dedication to his craft provides a lasting testament to the power of art to document, interpret, and celebrate the world around us.