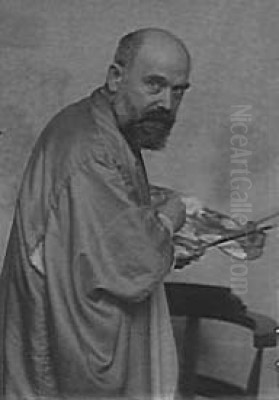

Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer stands as a significant figure in French art at the turn of the twentieth century, a versatile artist whose career gracefully navigated the currents of Symbolism and Art Nouveau. Born Lucien Lévy in Algiers on September 30, 1865, into a Jewish family, he later moved to Paris to pursue his artistic education. His long and productive life, ending on September 24, 1953, witnessed his evolution from a ceramicist to a celebrated painter and designer, leaving behind a rich legacy characterized by technical finesse, emotional depth, and a unique synthesis of diverse influences. His work, spanning painting, pastel, ceramics, and interior design, consistently reflects a profound engagement with beauty, mystery, and the inner life.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Ceramics

Lévy-Dhurmer's artistic journey began formally in 1879 when he entered the École Supérieure de Dessin et de Sculpture in Paris. His initial training focused on drawing and sculpture, laying a solid foundation for his later work. However, his early career path took a decisive turn towards the decorative arts. Also starting in 1879, he began working in the field of ceramics decoration, an area that would profoundly shape his aesthetic sensibilities.

A pivotal experience during this formative period was his employment from around 1887 to 1895 at the ceramic factory of Clément Massier in Golfe-Juan, located in the South of France near Vallauris. Initially a ceramic decorator, Lévy-Dhurmer rose to the position of artistic director. Working closely with Massier, a renowned innovator in ceramic techniques, Lévy-Dhurmer immersed himself in the craft. He reportedly studied pottery under Raphael Collin during this time. This period was crucial for his exploration of ceramic forms and glazes, particularly the metallic luster glazes inspired by Hispano-Moresque pottery and Islamic art, which Massier's workshop helped to revive and popularize. This early exposure to non-Western aesthetics, particularly the intricate patterns and iridescent surfaces of Islamic art, left an indelible mark on his artistic vision.

The Pivotal Journey to Italy and the Embrace of Painting

Despite his success in ceramics, Lévy-Dhurmer harbored ambitions as a painter. A disagreement with a colleague reportedly led to his departure from Massier's factory around 1895. This break provided the opportunity for a transformative journey. He traveled extensively through Italy that year, immersing himself in the masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance. The works of masters like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo deeply impressed him, influencing his approach to form, composition, and the rendering of human emotion. The subtle modeling and enigmatic atmospheres found in Leonardo's work, often described by the term sfumato, would resonate in Lévy-Dhurmer's later pastel portraits.

Upon his return to Paris, inspired and artistically reinvigorated, he decided to dedicate himself primarily to painting. It was at this juncture, in 1896, that he adopted the hyphenated surname "Lévy-Dhurmer," adding his mother's maiden name (Goldhurmer, shortened) to distinguish himself and perhaps signal his new artistic identity. This marked a definitive shift in his career focus.

His debut as a painter came swiftly and successfully. In 1896, he held his first solo exhibition at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris, showcasing a collection of paintings and, significantly, pastels. The exhibition was met with considerable acclaim from both the public and critics, establishing him almost immediately as a noteworthy artist within the Parisian scene. His mastery of the pastel medium, in particular, drew significant attention.

The Symbolist Vision: Mystery, Mood, and Pastel Mastery

Lévy-Dhurmer quickly became associated with the Symbolist movement, although he maintained a degree of independence and never formally joined any specific Symbolist group. Symbolism, emerging in the late 19th century as a reaction against Realism and Impressionism, sought to express subjective emotions, ideas, and spiritual truths rather than objective reality. Artists like Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes were key figures in this movement, exploring themes of dreams, mythology, spirituality, and the inner psyche.

Lévy-Dhurmer's work perfectly captured the Symbolist ethos. His paintings and pastels are characterized by their dreamlike atmospheres, melancholic moods, and suggestive ambiguity. He excelled at portraying introspective figures, often women, enveloped in environments that seemed to reflect their inner states. His technique, especially in pastel, was exceptionally refined. He employed delicate lines, soft, harmonious color palettes, and subtle gradations of tone to create ethereal effects. His handling of light and shadow was particularly adept, often used to enhance the sense of mystery and emotional depth, reminiscent perhaps of the atmospheric effects achieved by James McNeill Whistler in his pastels and nocturnes.

Comparisons have been drawn between the melancholic beauty of his figures and those of the British Pre-Raphaelites, such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti or Edward Burne-Jones, though Lévy-Dhurmer's style remained distinctly French and infused with fin-de-siècle sensibilities. While primarily a Symbolist, some critics noted an Impressionist sensitivity to light and color in his work, perhaps echoing the pastel innovations of Edgar Degas or the chromatic vibrancy found in landscapes by Claude Monet, albeit filtered through a more subjective lens.

Representative Works: Portraits and Evocative Landscapes

Several works stand out as exemplars of Lévy-Dhurmer's Symbolist period. Perhaps his most famous piece is the Portrait of Georges Rodenbach (1896), now housed in the Musée d'Orsay. This pastel portrait depicts the Belgian Symbolist writer, author of the influential novel Bruges-la-Morte, emerging from a misty, blue-toned backdrop suggestive of the canals and melancholic atmosphere of Bruges, the city central to Rodenbach's work. The integration of the figure with his environment, the introspective gaze of the sitter, and the overall evocative mood make it a quintessential Symbolist portrait. Lévy-Dhurmer's friendship with Rodenbach highlights his connections within the literary and artistic circles of the time.

Another significant pastel from the same period is Bruges-la-Morte (1896), directly inspired by Rodenbach's novel. It depicts a spectral female figure gliding along a canal, embodying the themes of memory, loss, and the haunting presence of the past that permeate the book. Works like Florence also showcase his ability to imbue landscapes and cityscapes with deep emotional resonance, transforming topographical views into soul-states or idealized visions. An earlier work, Portrait of a Young Woman (1891), already hints at the sensitivity and delicate execution that would become his hallmark.

His female portraits often depict women in states of reverie or contemplation, sometimes adorned with symbolic elements like flowers or musical instruments, suggesting connections to nature, art, and the inner world. These figures possess a quiet intensity and an enigmatic quality that invites interpretation, aligning with the Symbolist goal of suggesting rather than stating.

Art Nouveau and the Decorative Arts: A Continuing Passion

While Lévy-Dhurmer gained fame as a painter, he never entirely abandoned the decorative arts. His background in ceramics continued to inform his work, and he became a significant figure within the Art Nouveau movement, which emphasized organic forms, flowing lines, and the integration of art into everyday life. His earlier experiences with Islamic and Japanese art (Ukiyo-e prints by artists like Hokusai or Hiroshige were widely influential) found expression in the stylized natural motifs and elegant designs characteristic of Art Nouveau.

He continued to design ceramics, often featuring the iridescent glazes he had explored with Clément Massier, applied to sinuous, nature-inspired forms. His work in this field is considered part of the revival of artistic pottery in France, alongside contemporaries like Ernest Chaplet or Auguste Delaherche.

Beyond ceramics, Lévy-Dhurmer demonstrated remarkable talent in furniture and interior design. He embraced the Art Nouveau ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art), where the artist designs not just individual objects but entire environments. A notable example is the Wisteria Dining Room he designed around 1910-1914 for the villa of Auguste Rateau in Wazières. This immersive interior featured intricately carved woodwork with wisteria motifs, specially designed furniture, lighting fixtures, and possibly even textiles, creating a unified and harmonious artistic statement. His designs often incorporated flowing lines, botanical themes, and fine craftsmanship, comparable in spirit to the work of leading Art Nouveau designers like Émile Gallé or Louis Majorelle, yet possessing his own distinct refinement. He is also known to have designed wallpapers, further demonstrating his commitment to integrating art into the domestic sphere.

Influences, Connections, and Artistic Independence

Lévy-Dhurmer's art represents a confluence of diverse influences. The foundational impact of Islamic art and the Renaissance masters has already been noted. Japanese Ukiyo-e prints provided models for flattened perspectives, decorative patterning, and elegant linearity, elements visible in both his paintings and decorative designs. The literary Symbolism of poets like Charles Baudelaire, with its emphasis on suggestion and synesthesia (linking senses, like sound and sight), resonated deeply with his artistic aims. He was also reportedly influenced by the music of composers like Claude Debussy, whose atmospheric and evocative compositions shared a kinship with Lévy-Dhurmer's visual world.

He moved within a vibrant artistic milieu. His collaboration with Clément Massier and friendship with Georges Rodenbach were significant. He was also associated with fellow Symbolist painters such as Émile Bernard (though Bernard's path diverged towards Cloisonnism and Synthetism earlier), Alphonse Osbert, known for his mystical landscapes bathed in twilight, and Carlos Schwabe, whose Symbolist works often featured allegorical figures and intricate detail. He would certainly have been aware of, and likely influenced by, the major figures of French Symbolism like Puvis de Chavannes, Moreau, and Redon. His sensitive use of pastel and atmospheric effects also invites comparison with Whistler, while the intense, often melancholic, portrayal of figures finds parallels in the work of Belgian Symbolists like Fernand Khnopff.

Despite these connections and shared sensibilities, Lévy-Dhurmer maintained a distinct artistic identity. He did not adhere strictly to any single doctrine and navigated his own path, blending influences and techniques to create a highly personal style. His independence allowed him the freedom to explore various media and themes throughout his long career.

Later Life and Continued Creation

In 1914, Lévy-Dhurmer married Emmy Fournier. Some accounts suggest that this marriage did not provide the same level of artistic inspiration as his earlier experiences, and that some of his most powerful Symbolist works predate or coincide with periods of personal solitude or transition. However, this is speculative, and he certainly continued to produce art throughout his later life.

His later work saw a continued interest in landscape painting, often depicting scenes from Europe and North Africa, reflecting his travels. While perhaps less intensely focused on the overtly mystical themes of his peak Symbolist period, these later works often retained a sensitivity to light and atmosphere. He continued to exhibit his work and remained a respected figure in the French art world. He lived to the age of 88, passing away in Le Vésinet, near Paris, in 1953.

Legacy and Critical Reception

Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer enjoyed considerable success and critical acclaim during his lifetime. Critics praised his technical skill, particularly his mastery of pastel, and his ability to convey subtle emotions and dreamlike states. He was recognized as a key exponent of Symbolism and a significant contributor to the Art Nouveau movement, particularly in the realm of ceramics and integrated interior design.

Today, his work is held in major museum collections worldwide, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Louvre, and prominently at the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, which houses several of his key pieces. He is remembered as an artist of great sensitivity and refinement, whose work bridges the gap between painting and the decorative arts. His unique synthesis of influences – from Islamic patterns and Renaissance grace to Symbolist introspection and Art Nouveau elegance – resulted in a body of work that remains captivating for its beauty and emotional depth.

His legacy lies in his contribution to the Symbolist exploration of the inner world and his role in the Art Nouveau movement's elevation of decorative arts. He demonstrated that technical virtuosity could be combined with profound feeling, creating art that was both aesthetically pleasing and intellectually stimulating. His ability to work across multiple disciplines underscores the holistic approach favored by many artists of his era, seeking to infuse art into all aspects of life.

Conclusion

Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer was a multifaceted artist whose career reflects the rich artistic ferment of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. From his beginnings in ceramics, influenced by the exoticism of Islamic art, through his transformative encounter with the Italian Renaissance, he emerged as a leading figure in French Symbolism, renowned for his evocative pastels. Simultaneously, he embraced the ideals of Art Nouveau, creating exquisite ceramics and integrated interiors. His work, characterized by technical mastery, delicate beauty, and a pervasive sense of mystery and melancholy, continues to resonate. As a painter, designer, and ceramicist, Lévy-Dhurmer left an important and enduring mark on the landscape of modern art, celebrated for his unique vision and versatile talents.