Stanisław Wyspiański stands as a colossus in the landscape of Polish art and literature. Born on January 15, 1869, and passing away prematurely on November 28, 1907, his relatively short life blazed with an astonishing creative energy that left an indelible mark on the cultural identity of Poland. Active during the vibrant Młoda Polska (Young Poland) period, Wyspiański was not merely an artist confined to one discipline; he was a true Renaissance man of his era – a celebrated playwright, poet, painter, graphic artist, and designer of interiors, furniture, and stained glass. His work synthesized the burgeoning trends of European modernism with deeply rooted Polish traditions and national aspirations, making him arguably the most versatile and influential Polish artist of his time. His birthplace and the city that remained central to his life and work was Kraków, the historical heart of Poland, where he died and was laid to rest in the Crypt of the Meritorious at Skałka Church, an event marked by national mourning.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Kraków

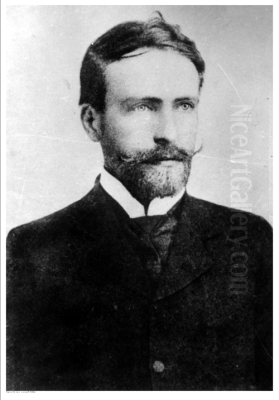

Stanisław Wyspiański was born into an environment steeped in art and history. His birthplace at 14 Krupnicza Street in Kraków placed him in the cultural nucleus of Poland. His father, Franciszek Wyspiański, was a sculptor, providing young Stanisław with early exposure to the artistic world, although the father's struggles with alcohol later cast a shadow over the family. Following his mother's death when he was seven, Stanisław was raised by his aunt and uncle, Kazimierz and Joanna Stankiewicz, whose home was a meeting place for Kraków's intellectual and artistic elite. This environment undoubtedly nurtured his burgeoning talents.

His formal artistic education began at the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts. Here, he studied under the tutelage of Jan Matejko, the preeminent Polish historical painter of the 19th century. Matejko recognized Wyspiański's talent and involved him, along with other students like Józef Mehoffer, in the monumental project of creating polychrome murals for the restored St. Mary's Basilica in Kraków. While Matejko's influence provided a strong foundation in historical themes and academic technique, Wyspiański's artistic vision soon began to diverge, seeking more modern forms of expression. His studies also included history, art history, and literature at the Jagiellonian University, broadening his intellectual horizons and fueling his interdisciplinary approach.

Parisian Exposure and the Development of a Unique Style

Like many aspiring artists of his generation, Wyspiański sought inspiration beyond Poland's borders. Between 1890 and 1894, he made several trips across Europe, spending significant time in Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Prague, and, crucially, Paris. The French capital was the epicenter of artistic innovation, and Wyspiański immersed himself in its vibrant scene. He frequented museums, galleries, and theatres, absorbing the latest trends. He encountered the works of the Post-Impressionists, particularly Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh, whose bold use of color and expressive line resonated with him.

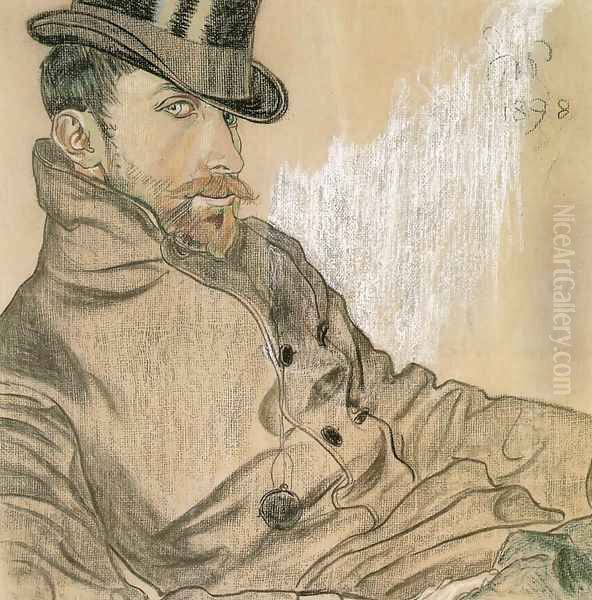

He was also deeply influenced by the Symbolist movement in both art and literature, and the burgeoning Art Nouveau style, with its emphasis on sinuous lines, organic forms, and the integration of art into everyday life. Artists like Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, known for his large-scale allegorical murals, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, with his dynamic depictions of Parisian life, likely contributed to his evolving aesthetic. During his time in Paris, Wyspiański honed his skills, particularly in pastel, a medium he would master and make distinctively his own. He developed a characteristic style marked by strong, flowing contour lines, often filled with flat planes of color or delicate shading, combining decorative elegance with profound psychological depth.

Master of Pastel: Portraits and Intimate Scenes

While Wyspiański worked in various media, pastel became his preferred medium for painting, allowing for both immediacy and subtle tonal variations. He achieved remarkable proficiency, using pastels to create works of striking emotional intensity and visual appeal. His subjects were often drawn from his immediate surroundings: intimate portraits of his friends, family, and, most notably, his own children and wife. These works are far from mere sentimental depictions; they possess a penetrating psychological insight and a distinctive linear quality.

His portraits of his children – Helena, Mietek, and Staś – are among his most beloved works. He captured their fleeting expressions and innocent gazes with tenderness yet without idealization, often depicting them sleeping or absorbed in quiet contemplation. These works showcase his mastery of line and his ability to convey vulnerability and the inner life of his subjects. His numerous self-portraits are equally compelling, charting his own physical and emotional journey, often with unflinching honesty. The famous Self-Portrait with Wife (1904) depicts him alongside Teodora Teofila Pytko, capturing a moment of quiet domesticity tinged with a certain gravity, reflecting perhaps the complexities of their relationship and the artist's own introspective nature. His method often involved intense, prolonged observation of his models, seeking to capture their essential character beneath the surface appearance.

Symbolism and National Identity in Paint

Wyspiański's painting extended beyond portraiture into the realm of Symbolism, deeply intertwined with the cultural and political climate of partitioned Poland. The Young Poland movement, of which he was a leading figure, sought to revive the national spirit through art and literature, often employing symbolism derived from Polish history, folklore, and landscape. Wyspiański's work in this vein is charged with allegorical meaning, reflecting on Poland's past, present struggles, and hopes for future independence.

One of his most iconic symbolic images, though originating as a stage direction in his play Wesele, is the Chochoł (plural: Chochoły). These are straw wrappings used to protect rose bushes from winter frost. In Wyspiański's work, the Chochoł became a potent symbol of dormancy, stagnation, and the unrealized potential of the Polish nation, trapped in a state of lethargy but holding the promise of future blossoming. He depicted these figures in pastel works like Chochoły (Straw Men), creating haunting images that resonated deeply with the Polish psyche. Other works, including his illustrations for Homer's Iliad and his designs related to Polish legends and historical figures, further demonstrate his use of symbolism to explore universal themes through a distinctly Polish lens.

Revolutionizing Polish Theatre: The Playwright

While his visual art secured his fame, Wyspiański's contributions as a playwright were arguably even more revolutionary, earning him the title "Father of Modern Polish Drama." He authored nearly forty plays, radically transforming Polish theatre by integrating poetic language, symbolic imagery, visual design, and contemporary social commentary. He drew inspiration from Greek tragedy, Shakespeare, and the great Polish Romantic poets known as the "Three Bards" – Adam Mickiewicz, Juliusz Słowacki, and Zygmunt Krasiński – often engaging in a dialogue with their works while forging a new path. Wyspiański himself came to be regarded by many as the "Fourth Bard."

His undisputed masterpiece is Wesele (The Wedding), first staged in Kraków in 1901. Based on the real-life wedding of his friend, the poet Lucjan Rydel, to a peasant woman from the village of Bronowice, the play masterfully blends realism, satire, and visionary symbolism. The first act realistically portrays the wedding party, highlighting the uneasy interactions and underlying tensions between the Kraków intelligentsia and the peasantry. The second act descends into a dreamlike, symbolic realm where characters are visited by ghosts from Polish history and legend (including figures invoked by Matejko's paintings), exposing their hidden desires, fears, and the nation's collective traumas. The final act culminates in the haunting dance led by the Chochoł, symbolizing the nation's paralysis and inability to act for independence. Wesele was a theatrical bombshell, a profound and critical examination of the Polish condition that continues to be a cornerstone of the Polish theatrical repertoire.

Other significant dramatic works include Wyzwolenie (Liberation), a metatheatrical exploration of art, freedom, and national identity; Akropolis, which reimagines figures from Wawel Cathedral tapestries coming to life on Easter Eve, linking Polish history with classical and biblical traditions; Legenda (Legend) I and II, dealing with Polish myths; and Klątwa (The Curse), a stark village tragedy. In all his plays, Wyspiański demonstrated a unique ability to fuse poetic drama with sharp social critique and stunning visual concepts.

Total Art: Design and the Applied Arts

Wyspiański fervently believed in the concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art, striving to unify architecture, painting, sculpture, and the applied arts into a cohesive aesthetic whole. He sought to infuse everyday life with artistic beauty and meaning, extending his creative vision beyond the canvas and the stage into the realm of design. His contributions in this area were groundbreaking and highly influential, particularly within the Polish iteration of the Art Nouveau movement.

His most celebrated achievements in design include his stained glass windows. Working alongside collaborators like Józef Mehoffer on early projects, he developed a mastery of the medium. His windows for the Franciscan Church in Kraków are masterpieces, particularly the monumental God the Father – Let It Be!, depicting the creation with dynamic energy, and the series based on the elements and floral motifs, showcasing his signature sinuous lines and vibrant color palette. He also created designs for Wawel Cathedral, though not all were realized, envisioning a comprehensive symbolic program linking Poland's royal history with its spiritual destiny.

His vision of total design extended to interiors. His most complete project was the decoration of the House of the Medical Society in Kraków (1904), where he designed everything from the murals and stained glass to the furniture, light fixtures, and even the staircase railings, creating a harmonious and distinctly Polish Art Nouveau environment. His furniture designs often featured stylized floral motifs inspired by local flora, combining functional simplicity with decorative richness. He also applied his talents to graphic design, creating innovative typography, book covers, and posters, often for his own plays, ensuring a unified visual identity for his work.

The Young Poland Movement and Contemporaries

Stanisław Wyspiański was a central figure, perhaps the most defining one, of the Młoda Polska (Young Poland) movement, which flourished roughly between 1890 and 1918. This artistic and literary period was characterized by a rejection of Positivist realism in favor of Symbolism, Expressionism, and Aestheticism, often infused with a strong sense of national consciousness and a fascination with folklore, psychology, and the mystical. Wyspiański embodied the movement's ideals of artistic synthesis and the artist's role as a spiritual leader.

He moved within a vibrant circle of contemporaries, engaging in both collaboration and, at times, rivalry. His relationship with his former teacher, Jan Matejko, evolved from mentorship to a respectful divergence of artistic paths. He maintained a close friendship and artistic partnership with Józef Mehoffer, another leading Young Poland artist, collaborating on stained glass projects and sharing similar artistic circles. A more complex relationship existed with Stanisław Witkiewicz (father of the later avant-garde artist Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz), a prominent art critic, painter, and architect known for developing the Zakopane style. While both were towering figures of Polish modernism, their approaches and personalities differed, leading to a degree of rivalry, particularly concerning national style and the direction of Polish art.

Wyspiański's artistic milieu included many other significant figures of the Young Poland era. Among them were Jacek Malczewski, the leading Polish Symbolist painter known for his allegorical works; Olga Boznańska, a renowned portraitist with a distinctive psychological style, often compared to Whistler; Władysław Ślewiński, who spent time in Pont-Aven and was associated with Gauguin's circle; the versatile Leon Wyczółkowski, master of landscape, portraiture, and graphic arts; Teodor Axentowicz, known for his elegant portraits and scenes of Hutsul folk life; Wojciech Weiss, whose work evolved towards Expressionism; Kazimierz Sichulski, also known for Hutsul themes and stained glass; and Ferdynand Ruszczyc, a painter celebrated for his symbolic landscapes. These artists, along with writers and musicians, created a rich cultural ferment in which Wyspiański played a pivotal role.

Personal Life: The Man Behind the Art

Despite his immense public profile as an artist, Wyspiański's personal life was marked by introspection, domesticity, and ultimately, tragedy. In 1900, he married Teodora Teofila Pytko, a peasant woman from a village near Kraków who had previously been his housekeeper and the mother of his first two children. This marriage across class lines was unconventional for the time and caused a stir within Kraków society, but it reflected Wyspiański's disregard for social conventions and perhaps his affinity for the perceived authenticity of peasant life, a theme explored in Wesele. Teodora became a frequent model for his art, appearing in numerous tender portraits alongside their children: Helena, Mietek, and Staś. He also adopted her son from a previous relationship, Teodor.

Contemporaries described Wyspiański as intense, often taciturn, and deeply absorbed in his work. He was sometimes referred to as the "Hermit of Kraków," suggesting a preference for solitude, though his home was also a hub for artistic discussion. His dedication to his art was all-consuming. This intensity was coupled with a growing physical frailty. For much of his adult life, he suffered from syphilis, an incurable disease at the time. The illness progressively weakened him, particularly in his final years, forcing him to sometimes draw strapped to a chair. Despite his declining health, his creative output remained astonishingly high until the very end.

His death in Kraków on November 28, 1907, at the age of just 38, sent shockwaves through Poland. His funeral procession turned into a massive national demonstration, with crowds lining the streets from St. Mary's Basilica to the Skałka Church, where he was interred in the national pantheon alongside Poland's greatest cultural figures. It was a testament to the profound impact he had made in his short life.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Stanisław Wyspiański's legacy is monumental and multifaceted. He is universally acknowledged as one of Poland's most important and original artists, a national icon whose work continues to resonate deeply within Polish culture. His influence extends across multiple domains. In theatre, he fundamentally reshaped Polish drama, creating a model of modern, symbolic, and visually integrated theatre that influenced generations of directors and playwrights. Wesele remains arguably the most important Polish play ever written, constantly reinterpreted on stage and screen.

In the visual arts, he stands as a master of Polish Art Nouveau and Symbolism. His distinctive linear style, his mastery of pastel, and his groundbreaking stained glass designs left a lasting imprint. His concept of the "total work of art" inspired efforts to bridge the gap between fine arts and applied arts in Poland. His portraits, particularly of children, are cherished for their psychological depth and artistic finesse.

More broadly, Wyspiański's work embodies the spirit of the Young Poland era and its quest for national identity through cultural expression. He skillfully synthesized European modernist trends with native Polish traditions, history, and folklore, creating an art that was both universal in its themes and deeply rooted in its specific cultural context. His exploration of the Polish psyche, its burdens, and its aspirations continues to provoke thought and discussion. Though his life was tragically cut short, Stanisław Wyspiański's prolific output and visionary genius secured his place as a towering figure not only in Polish art history but also within the broader narrative of European modernism.

Conclusion

Stanisław Wyspiański was a force of nature in Polish culture. In less than four decades, he produced a body of work staggering in its scope, originality, and enduring power. As a painter, he captured the soul of his subjects with a unique linear grace. As a designer, he infused spaces and objects with the spirit of Polish Art Nouveau. As a poet and playwright, he forged a new language for the stage, dissecting the condition of his nation with unparalleled artistic vision. He was a synthesizer, a modernist, a patriot, and above all, a unique creative genius whose work continues to inspire and define Polish art and identity. His name rightly belongs among the great innovators of European culture at the turn of the 20th century.