Ludwig Gedlek stands as a significant figure in late 19th-century Polish art, an artist whose work navigated the complex currents of Realism, Romanticism, and the potent pull of national identity during a period when Poland itself did not exist as a sovereign state on the map of Europe. Born in 1847 in Kraków and passing away in Vienna in 1904, Gedlek dedicated much of his artistic output to depicting scenes drawn from Polish history, rural life, and particularly the vibrant, often romanticized world of the Zaporozhian Cossacks. His paintings, executed primarily in oil, captured a specific vision of the past and present, resonating with contemporary desires for cultural preservation and heroic narratives. Though he spent a considerable part of his career in Vienna, his thematic focus remained deeply rooted in the Polish and Ukrainian lands, contributing to the rich tapestry of Eastern European historical and genre painting.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings in Kraków

Ludwig Gedlek entered the world in Kraków in 1847. At this time, Kraków, though part of the Austrian Partition (known as Galicia), served as a vital spiritual and cultural capital for Poles. It was a city steeped in history, housing Wawel Castle, the ancient seat of Polish kings, and fostering a strong sense of national consciousness. This environment undoubtedly shaped the young Gedlek's sensibilities. While detailed records of his earliest training are scarce, the artistic atmosphere of Kraków, dominated by the historical pathos of masters like Jan Matejko, would have been inescapable. Matejko's monumental canvases depicting glorious or tragic moments from Poland's past set a high bar for history painting and emphasized art's role in sustaining national memory.

Gedlek made his public debut relatively early, exhibiting his work for the first time in 1863 at the Kraków Society of Friends of Fine Arts (Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Sztuk Pięknych, TPSP). This initial showing marked his entry into the professional art world of Poland. The TPSP was a crucial institution for artists in Galicia, providing a venue for exhibitions and fostering artistic exchange. Exhibiting there signified a level of competence and ambition. His early works likely explored themes common among young artists finding their voice, possibly including landscapes and local genre scenes, gradually developing the focus that would define his mature career.

The decision to further his studies abroad was a common path for ambitious artists from Poland during this era. While Kraków had its own School of Fine Arts, the academies in major European centers like Munich, Vienna, or Paris offered broader exposure, different pedagogical approaches, and access to international art markets. For Gedlek, the path led to the capital of the empire to which Kraków belonged: Vienna.

Viennese Education and Development

In 1873, Ludwig Gedlek secured a scholarship that enabled him to move to Vienna and enroll in the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts (Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien). This move was pivotal, placing him in one of Europe's major artistic hubs. Vienna, as the imperial capital, boasted rich collections, numerous exhibition opportunities, and a diverse artistic community. The Academy itself was a bastion of academic tradition, emphasizing rigorous training in drawing, composition, and technique.

During his studies in Vienna, which continued until around 1877, Gedlek had the opportunity to learn from notable professors. Among his teachers were Eduard Peithner von Lichtenfels (1833-1913) and Carl Wurzinger (1817-1883). Peithner von Lichtenfels was primarily known as a landscape painter, celebrated for his technical skill, atmospheric depictions, and often poetic or subtly humorous approach to nature. Studying under him would have honed Gedlek's abilities in rendering landscapes, which often formed crucial backdrops in his later historical and genre scenes.

Carl Wurzinger, on the other hand, was a history painter, working within the academic tradition. His guidance would have been invaluable for Gedlek's development in constructing narrative compositions, handling historical detail, and depicting the human figure in dramatic contexts. The combination of landscape and historical painting instruction provided Gedlek with a versatile technical foundation, allowing him to integrate figures convincingly into specific environments, whether tranquil countryside or chaotic battlefields.

Vienna became more than just a place of study for Gedlek; it eventually became his permanent home. He settled in the city, continuing to paint and also engaging in teaching activities, passing on his skills to a new generation. Despite residing in the Austrian capital, his artistic heart often seemed to remain in the lands of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, particularly focusing on themes that resonated with Polish identity and history.

The World of the Cossacks: A Central Theme

A defining feature of Ludwig Gedlek's oeuvre is his fascination with the Zaporozhian Cossacks. These fiercely independent, semi-nomadic warriors, primarily of Ukrainian origin but deeply intertwined with Polish history, inhabited the wild steppes along the Dnieper River. In the 19th century, particularly within the context of Romanticism and the search for national roots, the Cossacks became potent symbols. They represented freedom, martial prowess, a rejection of external authority, and a connection to a wild, untamed past. For Polish artists and writers, they were complex figures – sometimes allies, sometimes formidable foes, but always figures of intense historical and romantic interest.

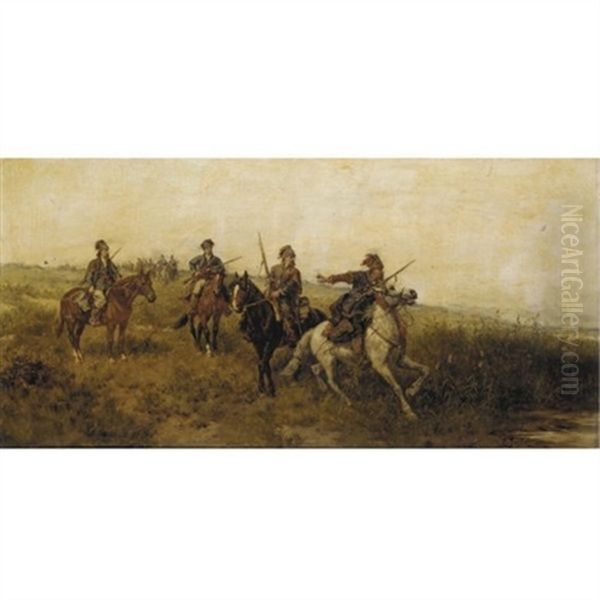

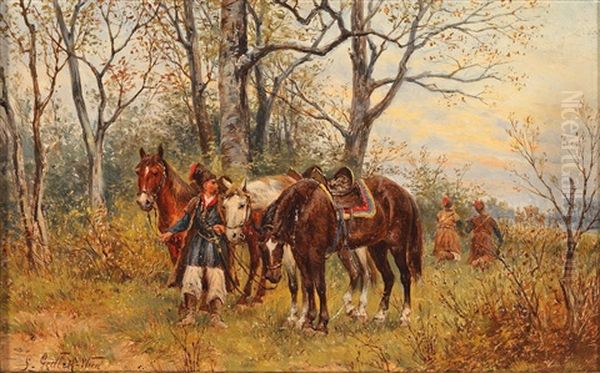

Gedlek's paintings frequently depict Cossacks in various situations: on horseback patrolling the vast steppes, resting at encampments, engaging in skirmishes, or simply as evocative figures embodying a specific way of life. Works like Mounted Cossacks, now housed in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, exemplify this focus. Such paintings often emphasize the Cossacks' distinctive attire, their weaponry, and their inseparable bond with their horses, all set against expansive, atmospheric landscapes.

His interest in this subject matter placed him in dialogue with other prominent Polish artists who explored similar themes, most notably Józef Brandt (1841-1915). Brandt, a leading figure of the "Munich School" of Polish painters, became famous for his dynamic and meticulously detailed depictions of Cossack life, Polish cavalry charges, and scenes from 17th-century Polish history. While Gedlek developed his own style, the comparison with Brandt is often made due to their shared thematic territory. Both artists contributed significantly to the popular imagery of the Cossack in Polish art, capturing the romantic allure and historical weight associated with these figures.

Gedlek's Cossack scenes were not mere ethnographic studies; they carried symbolic weight. In a time when Poland was partitioned and lacked political independence, depictions of historical warriors and symbols of past strength served as a form of cultural resistance and a reminder of a proud heritage. The Cossack, as a figure resisting external control, could be subtly interpreted as an allegory for the Polish struggle for freedom.

Polish History, Rural Life, and Equestrian Art

Beyond the specific focus on Cossacks, Gedlek's work encompassed a broader range of subjects related to Polish history and rural existence. He painted scenes depicting Polish soldiers from various historical periods, often emphasizing their connection to the landscape and their horses. The horse, in fact, is a recurring motif in Gedlek's art, rendered with skill and understanding. Whether carrying a Cossack across the steppe, pulling a peasant cart, or standing ready for battle, horses are depicted not just as accessories but often as central elements of the composition, imbued with their own character.

Paintings like Na czatach (variously translated as 'In the Stable' or 'On Watch'), dated to the 1880s and now in the Milwaukee Art Museum, show a quieter aspect of military life. It depicts cavalrymen and their horses at rest, capturing a moment of calm amidst the implicit readiness for action. This work highlights Gedlek's ability to handle intimate genre scenes as well as more dynamic compositions. The attention to detail in the soldiers' uniforms and equipment, combined with the sensitive portrayal of the animals, is characteristic of his approach.

His depictions of rural life, such as On the Way to Market or Pferdefuhrwerk auf der Landstraße (Horse-drawn Cart on the Country Road), connect with a broader European interest in peasant themes during the 19th century. Artists across the continent turned to the countryside, sometimes idealizing it, sometimes documenting its hardships. For Polish artists, depicting rural life also had national significance, portraying the landscapes and people considered the heartland of the nation. Gedlek's scenes often feature horse-drawn carts, peasants in traditional dress, and specific regional landscapes, grounding his work in a tangible reality while often infusing it with a picturesque or nostalgic quality.

The painting Walka o Sztandar (The Fight for the Standard) is noted as one of his significant works, likely depicting a battle scene where the capture or defense of a military standard – a symbol of unit honor and identity – is the focal point. Such themes were popular in historical painting, offering opportunities for dramatic composition, dynamic action, and the expression of patriotic sentiment. Gedlek's skill in rendering movement, the chaos of battle, and the emotional intensity of conflict would have been showcased in such a work.

Artistic Style: Realism, Romanticism, and Detail

Ludwig Gedlek's style can be broadly characterized as belonging to the Realist tradition prevalent in the latter half of the 19th century, yet it retains elements of Romantic sensibility, particularly in its choice of historical and exotic themes. His approach was grounded in careful observation and accurate representation, especially concerning historical details, costumes, weaponry, and the anatomy of horses and humans. This commitment to accuracy aligns him with the broader movement of Realism that sought to depict the world with veracity.

However, Gedlek often imbued his realistic depictions with a sense of atmosphere, drama, or nostalgia that connects to Romanticism. His landscapes are not merely neutral backdrops but contribute significantly to the mood of the painting, whether conveying the vastness of the steppe, the intimacy of a forest clearing, or the gloom of an impending storm. His use of light and shadow could be dramatic, highlighting key figures or actions and enhancing the emotional impact of the scene. The choice of subjects like the Cossacks or historical battles inherently carries romantic connotations of heroism, freedom, and the picturesque past.

His technique involved careful brushwork, allowing for fine detail while maintaining a sense of painterly texture. His color palettes could vary depending on the subject and mood, sometimes employing earthy tones for rural scenes or stable interiors, other times using more vibrant colors for dramatic effect in battle scenes or depictions of traditional costumes. The influence of his Viennese training, particularly the emphasis on solid drawing and composition learned from teachers like Wurzinger and Lichtenfels, is evident in the structured quality of his works.

While based in Vienna, Gedlek's style also resonates with aspects of the "Munich School" of Polish painting, where artists like Józef Brandt, Józef Chełmoński, and the Gierymski brothers (Maksymilian and Aleksander) developed a form of Polish Realism focused on national themes, genre scenes, and landscapes, often characterized by technical proficiency and a somewhat dark or tonal palette. Though geographically separate for much of his career, Gedlek participated in this broader artistic current that sought to define a Polish national art through realistic depictions of its history, people, and land. His work differs, however, from the grand, often didactic historical narratives of Jan Matejko or the later Symbolist explorations of artists like Jacek Malczewski. Gedlek occupied a space closer to genre painting and historical illustration, focused on specific, often evocative moments rather than overarching allegories.

Exhibitions, Reception, and Legacy

Throughout his career, Ludwig Gedlek actively participated in the art life of both Poland and Vienna. He continued to exhibit his works in Kraków at the TPSP, maintaining his connection to his native city. He also showed his paintings in Warsaw, likely at the Zachęta – Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts, another crucial venue for Polish artists. His participation in exhibitions in these key Polish centers ensured his visibility within the national art scene.

Simultaneously, living and working in Vienna provided him access to the exhibition opportunities of the imperial capital. He likely exhibited at venues such as the Vienna Künstlerhaus. This dual presence allowed his work to be seen by different audiences and potentially engage with different critical perspectives. His paintings found buyers, entering private and public collections. The presence of Mounted Cossacks in the prestigious Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna attests to the recognition he achieved beyond Polish circles. Similarly, the acquisition of Na czatach by the Milwaukee Art Museum indicates the international reach of his work, likely through collectors or emigrants.

Gedlek's legacy lies primarily in his contribution to the visual culture surrounding Polish history and the Cossack theme. Alongside Józef Brandt and the Kossak family of painters (Juliusz and his son Wojciech, both renowned for equestrian and battle scenes), Gedlek helped shape the popular imagination of these subjects. His detailed, atmospheric, and often action-filled paintings provided compelling images that resonated with national sentiment and the romantic fascination with the past.

His work is representative of a significant strand in 19th-century Polish art – one that used realistic techniques to explore historical and genre themes tied to national identity. While perhaps not as innovative as some of his contemporaries who moved towards Impressionism or Symbolism, like Aleksander Gierymski or Stanisław Wyspiański, Gedlek mastered his chosen idiom. He created a consistent body of work characterized by technical skill, thematic focus, and an ability to evoke the spirit of the scenes he depicted.

His paintings continue to be appreciated for their historical detail, their dynamic compositions, and their evocative portrayal of a specific world. They offer insights into the cultural preoccupations of his time, particularly the way history and folklore were mobilized in the service of national feeling during the period of partitions. Artists like Gedlek played a crucial role in keeping Polish history and culture alive in the visual arts, creating images that were both informative and emotionally engaging. His dedication to these themes, pursued largely from his base in Vienna, underscores the enduring connection many Polish artists felt to their homeland, regardless of where they lived and worked. His contemporaries in Vienna might have included artists working in vastly different styles, like the opulent historicism of Hans Makart, highlighting the diverse artistic environment in which Gedlek operated while maintaining his distinct focus. His work can also be seen in the broader European context of historical and military painting, drawing perhaps on traditions established by French artists like Horace Vernet or sharing a commitment to realism found in German painters like Adolph Menzel, yet always filtered through his specific Polish lens. Even earlier Polish Romantics like Piotr Michałowski, known for his dynamic horse studies, can be seen as precursors in the national artistic lineage that Gedlek inherited and continued.

Conclusion: A Dedicated Painter of Polish Themes

Ludwig Gedlek (1847-1904) carved a distinct niche for himself within the landscape of 19th-century Polish and Central European art. Born in the cultural heartland of Kraków but spending much of his productive life in Vienna, he remained steadfastly focused on subjects drawn from Polish history, rural life, and the evocative world of the Zaporozhian Cossacks. Trained at the Vienna Academy under figures like Eduard Peithner von Lichtenfels and Carl Wurzinger, he developed a style grounded in Realism but infused with Romantic atmosphere and a keen eye for historical detail.

His numerous depictions of Cossacks, horses, soldiers, and peasants contributed significantly to the visual lexicon of Polish national identity during a time of political non-existence. Works such as Mounted Cossacks, Na czatach, and Walka o Sztandar exemplify his skill in composition, his mastery of equestrian subjects, and his ability to capture both action and quietude. He shared thematic ground with prominent contemporaries like Józef Brandt, Juliusz Kossak, and Wojciech Kossak, helping to popularize these subjects.

Though perhaps less formally innovative than some other artists of his generation, Gedlek's dedication to his chosen themes, his technical proficiency, and his consistent output earned him recognition in both Polish and Viennese art circles. His paintings, found today in collections in Europe and America, stand as testaments to his craft and as valuable documents of the cultural concerns and artistic trends of his era. Ludwig Gedlek remains an important figure for understanding the role of historical and genre painting in shaping and reflecting national consciousness in 19th-century Poland.