Luigi Crosio (1835-1915) was an Italian painter whose life and career spanned a period of significant artistic and social change in Italy and across Europe. While perhaps not possessing the revolutionary zeal of some of his contemporaries, Crosio carved a distinct niche for himself, creating works that resonated with popular taste, particularly in genre scenes, romantic historical depictions, and, most enduringly, religious art. His legacy is uniquely characterized by one particular image that transcended the art world to become a global icon of Marian devotion.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Turin

Luigi Crosio was born in 1835. Sources vary slightly on his exact birthplace, with some records indicating Acqui Terme, a town east of Tortona in the Piedmont region of Italy, while others suggest Alba, or a small town near Acqui Terme. Regardless of the precise location, his formative years were spent in a region rich with artistic heritage. His artistic talents led him to Turin, the vibrant capital of Piedmont, which was then a major cultural and political center, especially in the lead-up to Italian unification.

In Turin, Crosio enrolled at the prestigious Accademia Albertina di Belle Arti. Founded in 1678 and reformed in the 19th century, the Accademia Albertina was a cornerstone of artistic education in Italy. It trained generations of artists, emphasizing classical principles, life drawing, and the study of Old Masters, while also adapting to contemporary trends. Here, Crosio would have received a rigorous academic training, honing his skills in drawing, composition, and painting. His studies would have exposed him to the prevailing artistic currents of the mid-19th century, including late Romanticism and the burgeoning interest in historical and genre painting. Artists like Carlo Arienti and Enrico Gamba were influential figures at the Accademia during this period, shaping the institution's direction.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Crosio's artistic output was diverse, reflecting both his academic training and his keen understanding of the art market. He became known for his proficiency in several areas.

Genre Scenes and Romanticism

A significant portion of Crosio's work consisted of genre scenes, often imbued with a romantic sensibility. He frequently depicted charming, anecdotal moments from everyday life, or idealized scenes set in the 18th century. These paintings were characterized by their meticulous detail, elegant figures, and often sentimental or lighthearted narratives. This focus on romanticized historical settings was popular throughout Europe in the 19th century, offering an escape into a more picturesque past. His style in these works often featured a polished finish and careful attention to costume and setting, appealing to the tastes of the bourgeois collectors of the era.

Pompeian Scenes

Crosio also specialized in creating scenes inspired by the ancient Roman city of Pompeii. The ongoing excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum throughout the 18th and 19th centuries had captivated the European imagination, fueling a widespread fascination with classical antiquity. Artists across the continent, such as the British painter Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema or the French master Jean-Léon Gérôme, produced numerous works depicting daily life in the Roman world. Crosio contributed to this popular genre, reconstructing historical events or imagined moments from Pompeian life. These paintings often showcased his skill in rendering architectural details and classical figures, and they catered to a public eager for glimpses into this remarkably preserved ancient civilization.

Portraits

Like many academically trained artists of his time, Crosio also undertook portrait commissions. While perhaps not his primary focus, his portraits would have demonstrated his ability to capture a likeness and convey the personality of his sitters, adhering to the conventions of 19th-century portraiture. The demand for portraits was high, as they served as important markers of social status and personal identity.

Fascination with Opera

Turin, where Crosio lived and worked, had a thriving opera scene, centered around the Teatro Regio. Crosio developed a particular passion for opera, and this interest frequently manifested in his art. He was known to depict scenes from popular operas, capturing the drama, emotion, and elaborate staging of these theatrical productions. His operatic paintings often combined his skill in figurative composition with a flair for narrative and spectacle. This interest was shared by his family; his daughter Carola, who later married the renowned mathematician Giuseppe Peano, was also an opera enthusiast. This connection to the theatrical world provided a rich source of inspiration and subject matter for Crosio.

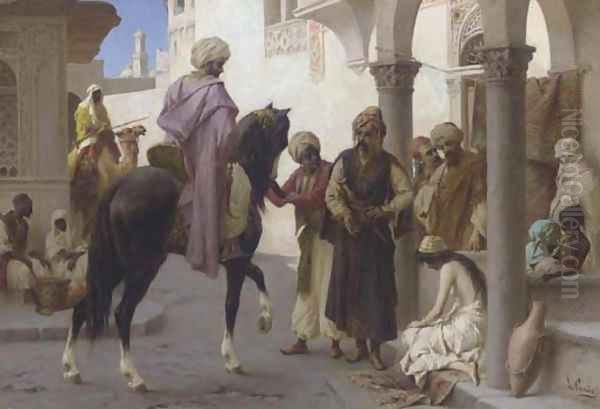

Orientalism

Crosio also explored Orientalist themes in some of his works, such as his painting The Beautiful Slave. Orientalism, the depiction of North African, Middle Eastern, and Asian cultures by Western artists, was a prominent and complex artistic movement in the 19th century. Artists like Eugène Delacroix, Jean-Léon Gérôme, and the Spanish painter Mariano Fortuny y Marsal, traveled to these regions or drew upon literary and visual sources to create exotic and often romanticized images. Crosio's The Beautiful Slave, with its depiction of a reclining odalisque figure in an opulent, vaguely Eastern setting, complete with Roman architectural elements, aligns with this trend. These works often blended fantasy with ethnographic detail, appealing to a European audience fascinated by the "exotic."

The Masterpiece: Refugium Peccatorum Madonna / Mother Thrice Admirable

Despite his varied output, Luigi Crosio is overwhelmingly remembered today for a single religious painting: Refugium Peccatorum Madonna (Madonna, Refuge of Sinners). Commissioned in 1898, this work was destined to achieve a level of fame and devotional significance that likely surpassed any of the artist's other creations during his lifetime.

The painting depicts the Virgin Mary tenderly holding the Christ Child. Mary is portrayed with a gentle, loving expression, her gaze directed softly downwards, while the Child Jesus looks out towards the viewer, one hand raised in a gesture of blessing or acknowledgement, the other resting on His mother. The composition is intimate and focuses on the close bond between mother and child. The style is soft and idealized, with a warm palette and a sense of serene piety. It draws on a long tradition of Marian iconography but presents it with a particular tenderness and accessibility that resonated deeply.

The history of this painting's rise to prominence is intertwined with the Schoenstatt Apostolic Movement, a Roman Catholic Marian movement founded in Germany in 1914 by Father Joseph Kentenich. In 1915, a year after the movement's founding and the year of Crosio's death, a copy of Crosio's Refugium Peccatorum Madonna was donated to the original Schoenstatt Shrine, a small former chapel in Vallendar, near Koblenz. The image was soon retitled Mater Ter Admirabilis (Mother Thrice Admirable, or MTA), a title with historical roots in Marian devotion, particularly associated with the Jesuit Sodality of Our Lady in Ingolstadt in the 17th century.

For the Schoenstatt Movement, the MTA image became a central focus of their spirituality. It symbolizes Mary's role as a mother, an educator, and an intercessor, who leads believers closer to Christ. The image is seen as representing the "covenant of love" that members of the movement make with Mary. From this small chapel in Germany, the Schoenstatt Movement grew into an international organization, and with it, the MTA image spread across the globe. Today, faithful replicas of the original Schoenstatt Shrine, each containing a copy of Crosio's painting, can be found in numerous countries, making Mother Thrice Admirable one of the most widely reproduced and recognized Marian images in the modern Catholic world.

The enduring appeal of Crosio's MTA lies in its gentle humanity and its depiction of a loving, approachable Madonna. It avoids the sternness or remote majesty of some earlier religious art, instead offering an image of maternal tenderness and divine grace that speaks directly to the heart of the faithful.

Other Notable Works

While the MTA image overshadows his other works in terms of global recognition, Crosio produced a considerable body of paintings throughout his career. Some other titles attributed to him include:

The Beautiful Slave: As mentioned, an example of his Orientalist work, showcasing a reclining female figure in an exoticized setting, blending classical and operatic influences. It is believed that one of his four daughters may have served as the model for this painting.

The Curate's Bible: This title suggests a genre scene, possibly depicting a moment of domestic piety or clerical life, a common theme in 19th-century art.

Lady with Greyhounds and a Parrot: This work, likely a portrait or an elegant genre scene, points to his engagement with depictions of aristocratic or bourgeois leisure.

Moorish Scene: The Dancer: Another example of his Orientalist interests, focusing on the theme of dance, which was a popular subject in Orientalist art.

Grand-Père and Scène Pompéienne: These works, known from copperplate prints dated 1898, further illustrate his engagement with sentimental genre scenes and Pompeian reconstructions.

Many of his works were reproduced as prints, which helped to popularize his images and make them accessible to a wider audience.

Crosio as a Lithographer and Illustrator

Beyond his work as a painter, Luigi Crosio was also a skilled draughtsman and lithographer. Lithography, a planographic printing process invented in the late 18th century, became immensely popular in the 19th century for its ability to reproduce images with great fidelity and artistic nuance. Artists like Honoré Daumier in France and Adolf Menzel in Germany demonstrated the expressive potential of the medium.

Crosio utilized his skills in lithography to create prints of his own paintings and potentially to illustrate books and other publications. This aspect of his career was important for disseminating his work and contributing to his income. His involvement in publishing books and images indicates an entrepreneurial side to his artistic practice, common among artists who sought to reach a broader public beyond elite collectors. The commercial appeal of his genre scenes and romantic depictions made them well-suited for reproduction.

Personal Life and Family

Details about Luigi Crosio's personal life are somewhat scarce, as is often the case for artists who were not at the very forefront of avant-garde movements or major national figures. He lived and worked primarily in Turin for most of his career. It is known that he had several daughters, who reportedly often served as models for his paintings. This practice of using family members as models was common among artists.

One of his daughters, Carola Crosio, married Giuseppe Peano (1858-1932) in 1887. Peano was a highly influential Italian mathematician, a founder of mathematical logic and set theory, known for the Peano axioms and his work on space-filling curves. This connection links the Crosio family to the intellectual and academic circles of Turin. Carola herself shared her father's interest in opera. Luigi Crosio passed away in Turin in 1915, at the age of 80.

Crosio in the Context of 19th-Century Italian Art

To fully appreciate Luigi Crosio's career, it's helpful to place him within the broader context of 19th-century Italian art. The period was marked by significant political and social upheaval, culminating in the Risorgimento and the unification of Italy in 1861. Artistically, Italy saw a complex interplay of enduring academic traditions and emerging new movements.

The academies, like the Accademia Albertina where Crosio trained, continued to wield considerable influence, promoting history painting, portraiture, and classical ideals. Romanticism had a strong presence in Italy, with artists like Francesco Hayez (known for works like The Kiss) and Domenico Morelli creating dramatic historical and literary scenes.

Genre painting, the depiction of everyday life, also flourished, catering to the tastes of the growing middle class. Artists across Italy specialized in charming, anecdotal, or sentimental scenes. Crosio's work in this vein aligns with this broader European trend.

Simultaneously, movements like the Macchiaioli (including artists such as Giovanni Fattori and Telemaco Signorini) emerged, particularly in Florence. They advocated for a more realistic approach, painting outdoors (en plein air) and using "macchie" (patches or spots of color) to capture light and form, often depicting contemporary Italian life and landscapes. While Crosio's polished, academic style differed from the Macchiaioli's more radical approach, both reflected different facets of 19th-century artistic concerns.

In the latter part of the century, Symbolism and Divisionism began to take hold in Italy, while portraitists like Giovanni Boldini and Antonio Mancini gained international acclaim for their vibrant and psychologically astute depictions of high society. Crosio's career largely unfolded within the more traditional, commercially viable streams of academic and romantic genre painting. His interest in Pompeian scenes connected him to a pan-European neo-classical and historical revival, while his Orientalist works tapped into another widespread artistic fascination of the era, exemplified by French artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme and William-Adolphe Bouguereau, or the British painter Frederic Leighton.

Exhibitions and Reception

Luigi Crosio's works were exhibited during his lifetime, though detailed records of all his participations are not readily available. His paintings, particularly genre scenes and historical reconstructions, would have been suitable for the official Salons and exhibitions common in Italy and other European countries. The reproduction of his works as prints also ensured a wide, if less formal, "exhibition" of his art to the public.

For instance, copperplate prints of his works like Grand-Père and Scène Pompéienne were part of an exhibition titled "Escuela Francesca, S. XIX," indicating their circulation and appreciation. His works have also appeared in art auctions over the years, such as at the Dorotheum in Vienna, which demonstrates an ongoing, albeit modest, market interest in his non-religious paintings.

However, the most significant "exhibition" of his work is undoubtedly the permanent display of the Mother Thrice Admirable image in Schoenstatt shrines worldwide. This continuous, devotional presentation has given one of his paintings an unparalleled global reach, far exceeding what typical museum or gallery exhibitions could achieve.

The critical reception of Crosio's work during his lifetime would likely have been favorable within the circles that appreciated academic skill, charming narratives, and romantic sensibilities. He was not an avant-garde artist challenging artistic conventions, but rather a skilled practitioner working within established and popular genres.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Luigi Crosio's primary legacy today is undeniably tied to the Mother Thrice Admirable painting. Through its adoption by the Schoenstatt Movement, this image has become a significant piece of 20th and 21st-century Catholic iconography. Millions of people around the world are familiar with this image, even if they do not know the name of the artist who created it. In this sense, Crosio achieved a form of artistic immortality through a work that transcended its original context to become a beloved object of religious devotion.

Beyond the MTA, Crosio's other works offer a window into the popular artistic tastes of the late 19th century in Italy. His genre scenes, Pompeian reconstructions, and operatic depictions reflect the cultural interests and aesthetic preferences of his time. They showcase a competent and versatile artist, skilled in academic techniques and adept at creating appealing narrative images. While he may not be counted among the great innovators of Italian art, his career demonstrates the enduring appeal of well-crafted, accessible art that speaks to common human emotions and interests. His work as a lithographer also highlights the importance of print media in disseminating art and culture during this period, a role later taken over by photography and other reproductive technologies. Artists like Gustave Doré also achieved immense fame through widely circulated prints and illustrations.

Conclusion

Luigi Crosio represents a fascinating figure in 19th-century Italian art. An academically trained painter from Turin, he navigated the artistic landscape of his time by producing a diverse body of work that included romantic genre scenes, historical reconstructions of Pompeii, portraits, and depictions inspired by opera. His style was characterized by technical skill, attention to detail, and an ability to create charming and commercially appealing images.

While his broader oeuvre remains primarily of interest to specialists in 19th-century Italian art, his painting Refugium Peccatorum Madonna, transformed into Mother Thrice Admirable, has secured him a unique and lasting place in the history of religious art and popular devotion. This single image, reproduced countless times and venerated in Schoenstatt shrines across the globe, demonstrates the profound and often unpredictable ways in which art can transcend its original purpose and achieve a far-reaching cultural impact. Luigi Crosio's story is a reminder that an artist's legacy can be shaped by a single, resonant work that captures the imagination and touches the spiritual lives of millions.