James Jacques Joseph Tissot stands as a fascinating figure in nineteenth-century art. A French painter who found immense success in London, he navigated the complex currents of Realism, Academic tradition, and the burgeoning Impressionist movement, ultimately carving a unique path that led him from chronicling the fashionable elite to dedicating his final years to profound religious illustration. His life and work offer a compelling glimpse into the societal changes, artistic debates, and personal transformations of his era.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in the port city of Nantes, France, on October 15, 1836, Jacques Joseph Tissot (he later adopted the English "James") grew up in an environment connected to the world of textiles and fashion, as his father was a successful draper and his mother assisted in the business, also designing hats. This early exposure to fabrics and style arguably influenced his later meticulous attention to costume and detail in his paintings. Drawn to art, he moved to Paris around 1856 to pursue formal training.

He enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, studying under masters like Hippolyte Flandrin and Louis Lamothe, both pupils of the great Neoclassical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. This academic training instilled in him a strong foundation in drawing and composition. During these formative years, he also forged crucial friendships with fellow artists who would become major figures in their own right, notably Edgar Degas and the American expatriate James McNeill Whistler. Whistler, in fact, is credited with suggesting Tissot adopt the anglicized first name "James."

Tissot's early artistic inclinations leaned towards historical subjects, particularly medieval scenes. He was significantly influenced by the Belgian painter Henri Leys, whose work revived historical genres with a detailed, almost archaeological precision. Tissot exhibited at the Paris Salon for the first time in 1859, presenting works that reflected this historical interest. A key painting from this period is The Meeting of Faust and Marguerite (1860), exhibited at the 1861 Salon and later acquired by the French state for the Musée du Luxembourg (now likely housed in the Musée d'Orsay). This work demonstrated his technical skill and ability to handle complex narrative scenes, aligning him initially with a more traditional, academic approach.

The Parisian Scene: Capturing Modern Life

Around the mid-1860s, a significant shift occurred in Tissot's artistic direction. Moving away from historical themes, he began to focus intently on depicting contemporary Parisian life, particularly the world of elegant women and high society. This change coincided with a broader artistic interest in modern subjects, championed by figures like Édouard Manet, with whom Tissot also maintained contact and from whom he likely absorbed ideas about portraying the nuances of modern existence.

This new focus brought Tissot considerable success and acclaim. His paintings of stylishly dressed women in chic interiors or engaging in social rituals resonated with the public and critics alike. He developed a signature style characterized by meticulous detail, a polished finish, and an almost photographic clarity. His rendering of fabrics – silks, velvets, furs – was particularly admired, showcasing textures and patterns with extraordinary skill. These works were often compared to fashion plates, yet they possessed a psychological depth and narrative ambiguity that elevated them beyond mere illustration.

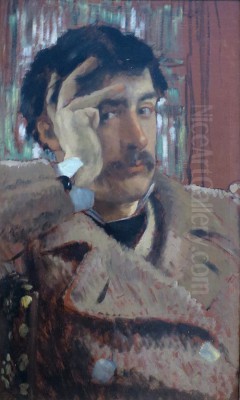

During this period, his friendships with Degas and Whistler continued, placing him within the orbit of avant-garde circles, even though his polished style differed markedly from the looser brushwork developing among the Impressionists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Degas famously painted a portrait of Tissot around 1867-68, depicting him in his studio surrounded by artworks, including a Japanese painting, hinting at another significant interest. Tissot was invited by Degas to participate in the First Impressionist Exhibition in 1874, but he declined, perhaps sensing his artistic path lay elsewhere, or perhaps already planning his move across the Channel.

London Years: Success and Scandal

The Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) and the subsequent turmoil of the Paris Commune marked another turning point. Tissot participated in the defense of Paris but, following the Commune's suppression, possibly due to political complications or simply seeking new opportunities, he relocated to London in 1871. He arrived with established connections and quickly integrated into the London art scene, achieving even greater commercial success than he had in Paris.

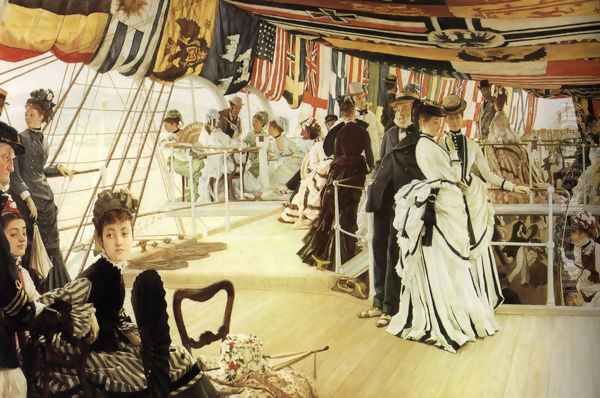

In London, Tissot continued to paint scenes of modern life, now focusing on British high society and the nuances of Victorian social etiquette. Works like The Ball on Shipboard (c. 1874), Hush! (The Concert) (c. 1875), and An Afternoon Tea capture the elaborate rituals, fashions, and subtle social dynamics of the era. His house in St John's Wood became a hub, featuring a large studio and conservatory that often appeared in his paintings. He earned substantial sums, appealing to wealthy industrialists and the aristocracy. His success extended to printmaking, particularly etching, and he contributed caricatures to the society magazine Vanity Fair under the pseudonym "Cöidé," further cementing his public profile.

His London life took a dramatic personal turn around 1876 when he met Kathleen Irene Kelly Newton, a young Irish divorcée with a complex past. She became his companion, muse, and the central figure in many of his paintings during the late 1870s and early 1880s. Works like The Hammock (1879) and Reverie often feature her likeness, capturing moments of quiet intimacy or contemplation, frequently set within the lush garden of his home. Their relationship, however, was unconventional for the time; Kathleen lived with Tissot, along with her children (one of whom, Cecil George Newton Ashburnham, is widely believed to have been Tissot's son). This arrangement likely caused social friction and may have contributed to Kathleen's relative seclusion. Tragically, Kathleen suffered from tuberculosis and died in 1882 at the age of 28. Her death devastated Tissot; shortly afterward, he abandoned his London life and returned to Paris.

Embracing Japonisme

Throughout his career, but particularly during his Paris and London periods, Tissot was deeply engaged with Japonisme – the European fascination with Japanese art and culture that swept across the continent following the reopening of Japan to the West in the 1850s. He was an early and avid collector of Japanese objects, textiles, and prints, and these often appeared as props in his paintings, signaling sophistication and aesthetic sensibility.

His interest went beyond mere props. Tissot absorbed compositional strategies from Japanese woodblock prints (ukiyo-e), experimenting with flattened perspectives, asymmetrical arrangements, unusual cropping, and decorative patterns. Paintings like Young Women Looking at Japanese Objects (1869) explicitly depict this interest, while others subtly incorporate Japanese aesthetics into their structure and mood. This engagement placed him alongside contemporaries like Whistler, Degas, Manet, and later artists like Vincent van Gogh, who also found profound inspiration in Japanese art. Tissot's role as a collector and his integration of Japanese elements into fashionable scenes made him a significant figure in popularizing Japonisme in both France and England.

A Spiritual Turning Point: The Religious Works

The death of Kathleen Newton in 1882 marked the end of Tissot's London chapter and precipitated a profound personal and artistic transformation. Returning to Paris, he experienced a religious reawakening around 1885. Accounts often state this occurred during a Mass at the church of Saint-Sulpice in Paris, where, while observing the fashionable crowd, he had a vision that redirected his artistic purpose towards religious subjects. He revived his Catholic faith with intense fervor.

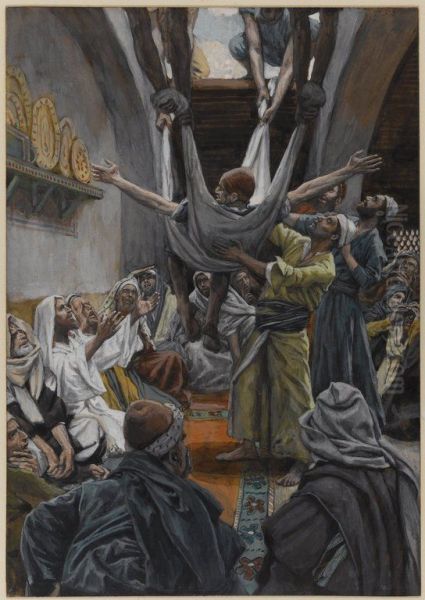

This spiritual conversion led to the most dramatic shift in his artistic output. He decided to dedicate the remainder of his life to illustrating the Bible, specifically the life of Christ. To ensure accuracy and authenticity, he embarked on extensive travels to the Middle East, visiting Egypt, Syria, and Palestine between 1886 and 1889, and again in 1896. He meticulously studied the landscapes, architecture, customs, and people, aiming to create illustrations that were geographically and culturally precise, moving away from idealized European depictions of biblical scenes.

The result was a monumental series of 365 gouache (opaque watercolor) illustrations depicting the life of Christ, from his birth to resurrection. These works, known collectively as The Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ, were characterized by their detailed realism, ethnographic accuracy, and intense spiritual feeling. When exhibited in Paris (1894-95), London (1896), and later toured in the United States, they achieved phenomenal popular success. The illustrations were widely reproduced in book form, becoming incredibly influential and shaping popular visual conceptions of the Bible for generations. Works like Jesus Traveling, The Sermon on the Mount, and The Return of the Prodigal Son (part of a later Old Testament series) exemplify this phase, showcasing his commitment to narrative clarity and devotional impact. He spent his final years working on a similar series illustrating the Old Testament, which remained unfinished at his death.

Artistic Style and Technique

James Tissot's artistic style is notable for its evolution and its synthesis of different influences. He began within an Academic framework, mastering draftsmanship and historical detail under the influence of Ingres's pupils and Henri Leys. His shift to modern life subjects saw him adopt a highly polished Realism, focusing on accurate depiction of contemporary fashion, interiors, and social manners. While contemporary with the Impressionists and friendly with key figures like Degas, he never adopted their characteristic loose brushwork or primary focus on capturing fleeting effects of light and atmosphere. Instead, his realism remained precise, detailed, and often imbued with a smooth, enamel-like finish.

His compositions, particularly during his London period and under the influence of Japonisme, often featured innovative arrangements, viewpoints, and cropping, adding a modern sensibility to his otherwise meticulous technique. He was a master of rendering textures, particularly fabrics, which lent his society paintings an air of luxurious verisimilitude.

The final phase of his career saw another stylistic adaptation. While the religious works retained his commitment to detail and accuracy, the medium shifted primarily to gouache. The style became less about capturing the sheen of high society and more focused on narrative clarity, historical reconstruction, and conveying spiritual intensity. Throughout his career, Tissot was also a skilled etcher, producing numerous prints that often mirrored the subjects of his paintings, further disseminating his images. His style, therefore, is a unique blend: rooted in academic training, refined through realist observation of modern life, inflected by Japanese aesthetics, and ultimately transformed by profound religious conviction.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Tissot's career unfolded amidst a vibrant and often contentious art world, and his relationships with fellow artists were significant. His early and intense friendship with Edgar Degas was formative for both, though it later cooled, partly due to differing artistic paths and perhaps political disagreements or personal slights. Degas's portrait of Tissot remains a testament to their early bond, while a later alleged incident, where Degas expressed anger over Tissot selling a gifted work, highlights the complexities of artistic friendships.

His relationship with James McNeill Whistler was also crucial, particularly in his youth. Whistler's influence and cosmopolitanism likely encouraged Tissot's own international outlook and his eventual move to London. The shared interest in Japonisme also linked them. Contact with Édouard Manet connected Tissot to the vanguard of French Realism and the painting of modern life.

Beyond these key figures, Tissot moved within wider artistic circles. In Paris, he would have known many artists associated with both the Salon and the avant-garde, potentially including figures like Gustave Moreau or the academic master Jean-Léon Gérôme. In London, he established connections within the British art establishment, interacting with painters possibly including figures associated with the Pre-Raphaelites like John Everett Millais or Dante Gabriel Rossetti, or classicists like Lawrence Alma-Tadema, whose detailed depictions of historical scenes share some affinity with Tissot's precision. His work for Vanity Fair also put him in contact with illustrators and caricaturists. His later religious work found parallels in the detailed illustrative traditions, perhaps echoing the narrative power seen in the work of Gustave Doré, though Tissot aimed for greater ethnographic accuracy. He also maintained connections with sculptors like Auguste Rodin. These interactions place Tissot not as an isolated figure, but as an artist actively engaged with the diverse artistic landscape of his time, even while maintaining his distinct stylistic identity.

Legacy and Market Presence

James Tissot left behind a diverse and compelling body of work. While his religious illustrations achieved immense popularity during his lifetime and shortly after, his reputation in the 20th century saw his society paintings, particularly those from his London period, gain increasing appreciation from collectors and art historians. These works are valued for their exquisite technique, their insightful (and sometimes subtly critical) portrayal of Victorian society, and their sheer visual appeal.

His paintings are held in major museums worldwide, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Tate Britain in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Brooklyn Museum (which holds the complete set of his Life of Christ gouaches).

In the art market, Tissot's major canvases command significant prices. As noted, his painting La Cheminée (c. 1869) carried a substantial estimate (£800,000-£1,200,000) at a Christie's auction in 2003, indicating the high value placed on his prime works. Museum acquisitions, such as Princeton University Art Museum purchasing Croquet (1878), further attest to his importance. While some market data sources list lower prices for works attributed to him, these may refer to prints, reproductions, or minor pieces, rather than his major oil paintings. The market generally reflects a strong demand for his elegant depictions of late 19th-century life. The specific auction price for works like David Slings the Stone (from his Old Testament series) is not readily available from the provided context, but his religious works, especially the original gouaches, are also highly valued historical and artistic artifacts.

Conclusion

James Jacques Joseph Tissot's artistic journey was one of remarkable transformation. From a promising painter of historical scenes in Paris, he evolved into a celebrated chronicler of high society in both the French capital and Victorian London. His keen eye for fashion, meticulous technique, and subtle narrative skill created captivating images that continue to fascinate viewers today. Yet, driven by personal tragedy and profound spiritual experience, he turned away from worldly success to dedicate his final years to illustrating the Bible with unprecedented ethnographic detail and devotional intensity. Straddling the worlds of academic tradition, modern realism, commercial success, and deep faith, Tissot remains a unique and significant figure, offering rich insights into the art, society, and spirituality of the late nineteenth century. His work endures as a testament to a life lived through dramatic change, reflected in an art of enduring elegance and conviction.