Luigi Mayer stands as a significant figure in late 18th-century European art, an artist of Italian-German heritage whose work provides an invaluable window into the Ottoman Empire and surrounding regions during a period of burgeoning Western interest. Born in Italy around 1755 and active until his death in 1803, Mayer became one of the earliest and most prolific European artists to dedicate his career to depicting the landscapes, ancient monuments, and daily life of the Near East. His detailed and evocative watercolours, later disseminated through aquatint engravings, shaped European perceptions of this world and left a lasting legacy for both art history and historical study.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Luigi Mayer's origins trace back to Italy, believed to have been born in Rome. His artistic training placed him under the tutelage of a master renowned for his dramatic depictions of architecture and ruins: Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778). Piranesi, famous for his etchings of Rome's ancient monuments and his imaginative "Carceri d'invenzione" (Imaginary Prisons), likely instilled in Mayer a fascination with antiquity, a mastery of perspective, and an appreciation for the grandeur of architectural forms, albeit expressed through a different medium.

Mayer's emerging talent gained recognition early on. In 1771, while still a young artist, he achieved success by winning a prize in a painting competition at the prestigious Accademia di San Luca in Rome. This accolade marked him as an artist of promise and likely facilitated his future opportunities. His early work, though less documented, would have been grounded in the Italian landscape and architectural traditions, influenced by the veduta (view painting) genre popularised by artists like Canaletto (1697-1768) and Francesco Guardi (1712-1793) in Venice, and adapted by Piranesi in Rome.

Patronage and Extensive Travels: The Ainslie Connection

Mayer's career took a decisive turn when he entered the service of Sir Robert Ainslie, the British Ambassador to the Ottoman Porte in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) from 1776 to 1794. This relationship proved pivotal. Ainslie, an enthusiastic collector and diplomat, employed Mayer as his personal artist, providing him with a salary (reportedly £50 per annum) and, more importantly, the opportunity to travel extensively throughout the vast territories under Ottoman influence or of interest to European antiquarians.

From roughly 1776 until Ainslie's departure, Mayer embarked on journeys that took him far beyond Constantinople. His itinerary included significant parts of the Ottoman heartland in Anatolia (Turkey), the Levant (Syria and Palestine), Egypt, the Balkans (including regions of modern Bulgaria and Romania), and the Greek islands. This extensive travel, undertaken under the ambassador's protection, allowed Mayer unparalleled access to sites rarely seen or documented by European artists before him. He became Ainslie's visual chronicler, tasked with recording landscapes, archaeological sites, local costumes, and scenes of everyday life.

Artistic Style, Technique, and the Orientalist Gaze

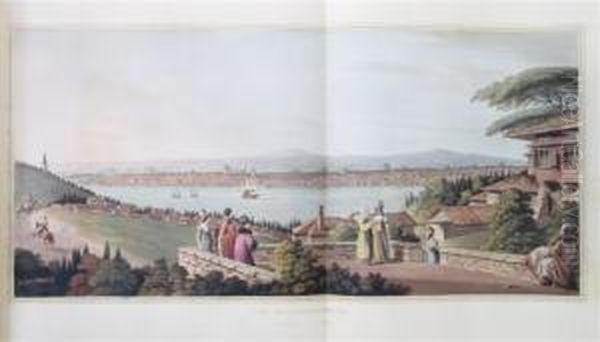

Luigi Mayer worked primarily in watercolour and gouache, often using pencil or charcoal outlines to establish his compositions. His style is characterized by a commitment to topographical accuracy combined with a refined artistic sensibility. He possessed a keen eye for detail, meticulously rendering architectural features, geological formations, and the textures of foliage and water. His works often convey a sense of atmospheric perspective and capture the specific quality of light in the Mediterranean and Near Eastern environments.

Mayer developed a technique noted for its speed and efficiency, allowing him to capture scenes quickly 'on the spot'. This immediacy lends a freshness and authenticity to his work, distinguishing it from studio compositions created from sketches or memory alone. While grounded in the documentary impulse of the Enlightenment – a desire to observe, classify, and record the world – his paintings are more than mere records. They possess an aesthetic quality, often imbued with a sense of picturesque beauty or the sublime grandeur of ancient ruins, echoing the sensibilities found in the works of landscape artists like Claude Lorrain (1600-1682) centuries earlier, but applied to novel subject matter.

His perspective, inevitably, was that of an 18th-century European. While striving for accuracy, his depictions contributed to the burgeoning field of Orientalism – the Western artistic and scholarly engagement with the East. His work presented the Ottoman world to European audiences, emphasizing aspects that aligned with Western interests: classical antiquity, biblical history, and the perceived exoticism of local customs and dress. He was among the first generation of artists, alongside figures like Jean-Baptiste Vanmour (1671-1737) who worked earlier in Constantinople, to systematically document this realm for Western consumption.

Subjects and Representative Works

Mayer's oeuvre covers a remarkable range of subjects, reflecting his extensive travels and Ainslie's diverse interests. Ancient ruins feature prominently, documenting the remnants of Greek, Roman, and Egyptian civilizations. He painted the temples of Egypt, the classical sites of Asia Minor, and the historical landscapes of Palestine. His depictions include famous locations such as the Pool of Bethesda, the Fountain of Samaria near Nablus, and the traditional site of the Tomb of Abraham in Hebron.

Cityscapes and contemporary life also captured his attention. He produced numerous views of Constantinople, including detailed portrayals of its harbour, fortifications like the Yedikule Fortress, and bustling street scenes. His travels in Egypt yielded images of Cairo, Alexandria (including works like The Aqueduct of the Ptolomies near Alexandria), and market scenes such as An Egyptian Market at Kafr el-Aton. Views of Jerusalem, often taken from vantage points like the Mount of Olives, provided European audiences with some of the most detailed contemporary images of the Holy City.

Many of Mayer's most famous works are known through the published collections commissioned by Ainslie. These include:

Views in Egypt, from the Original Drawings in the Possession of Sir Robert Ainslie, taken during his Embassy to Constantinople by Luigi Mayer (published 1801 onwards)

Views in Palestine, from the Original Drawings of Luigi Mayer (published 1804)

Views in the Ottoman Empire, chiefly in Caramania (Asia Minor) (published 1803)

Views in the Ottoman Dominions, in Europe in Asia, and some of the Mediterranean Islands (published 1810)

Specific well-known images derived from these series include the Colossal Sarcophagus near the Castle of Boudron (Bodrum, ancient Halicarnassus), various depictions of Egyptian temples at Karnak, Luxor, and Philae, and panoramic views of major cities.

Collaboration with Clara Barthold Mayer

During his time in Constantinople, Luigi Mayer met and, in 1795, married Clara Barthold. She was the daughter of a member of Sir Robert Ainslie's diplomatic entourage and was herself a talented artist. Clara became not just Luigi's wife but also his assistant and collaborator. Sources suggest they worked together on depicting the landscapes and, perhaps particularly, the costumes and daily life of late 18th-century Istanbul.

Clara's contribution should not be underestimated. She shared Luigi's passion for painting and continued to work after his death. Following Luigi's passing in London in 1803, Clara played a crucial role in overseeing the publication of his remaining drawings. She also continued her own artistic practice, exhibiting works independently. Their partnership represents an interesting example of artistic collaboration within the context of European engagement with the Ottoman world.

Dissemination through Aquatints and Reception

While Mayer produced original watercolours and drawings, his work reached a wide audience primarily through high-quality aquatint engravings. Sir Robert Ainslie funded the publication of lavish volumes featuring plates engraved after Mayer's originals, most notably by the skilled engraver Thomas Milton (1743-1827) and others like William Watts (1752-1851), whose name appears in connection with some prints. Aquatint, a technique capable of replicating the tonal variations of watercolour, was perfectly suited to reproducing Mayer's work.

These publications, often featuring descriptive texts in English, French, and sometimes German, began appearing around 1801, shortly before Mayer's death. They proved immensely popular in Britain and across Europe. For a public fascinated by travel accounts and the allure of the East, Mayer's detailed and seemingly objective views offered a captivating glimpse into distant lands. They served as visual resources for scholars, inspiration for designers, and vicarious travel for the armchair tourist. His work became a benchmark for topographical illustration of the region.

Despite the eventual popularity of the prints, some sources suggest Mayer himself may not have achieved widespread fame during his lifetime, with significant recognition coming posthumously through these publications. The delay between the creation of the drawings (mostly 1776-1794) and their publication starting in 1801 remains a point of interest.

Art Historical Significance and Legacy

Luigi Mayer occupies a crucial position in the history of European art, particularly within the development of Orientalism and topographical landscape painting. His contributions are manifold:

He was a pioneer. Working in the late 18th century, he was among the very first European artists to travel so extensively within the Ottoman Empire and produce such a comprehensive body of work dedicated to the region. His detailed, on-the-spot observations set a standard for subsequent artists.

He created invaluable historical documents. Before the advent of photography, Mayer's watercolours and the resulting prints provided some of the most accurate and detailed visual records of landscapes, monuments, and ways of life in the Near East, many of which have since changed or disappeared. His work remains a vital resource for historians, archaeologists, and anthropologists studying the period.

He influenced subsequent artists. Mayer's work, disseminated through prints, undoubtedly influenced later generations of artists who travelled to the East in the 19th century. Figures like David Roberts (1796-1864), known for his views of Egypt and the Holy Land, John Frederick Lewis (1804-1876), famous for his detailed scenes of Cairene life, and even potentially informing the context for Romantic Orientalists like Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) or the meticulous academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), would have been aware of the visual precedents set by Mayer. His work provided a foundation upon which later, often more romanticized or dramatic, interpretations were built.

He reflected Enlightenment values. Mayer's work embodies the Enlightenment's empirical spirit – the drive to explore, document, and understand the world through direct observation. His focus on classical ruins connected with the Neoclassical interests prevalent in Europe, championed by artists like Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), while his detailed recording of diverse cultures reflected a growing ethnographic curiosity. He operated within a different sphere than the high history painting of his time but shared the era's intellectual currents. His topographical approach can be compared to other travelling artists documenting different parts of the world, such as William Hodges (1744-1797) in India, or Thomas Daniell (1749-1840) and William Daniell (1769-1837), also in India.

Mayer in Context: Contemporaries and Influences

Placing Mayer within his artistic milieu requires looking at several contexts. His training with Piranesi connects him to the Italian tradition of architectural views and imaginative reconstructions of antiquity. His topographical focus aligns him with British watercolour traditions and the demand for accurate landscape views, even though he was not British himself. His role as a visual recorder for a diplomat places him in a lineage of artists accompanying expeditions or embassies.

Compared to Antoine Ignace Melling (1763-1831), another European artist who worked extensively in Constantinople slightly later and also enjoyed elite patronage, Mayer's scope was geographically broader, though Melling's large-scale engravings of Istanbul are perhaps more architecturally focused. Compared to the burgeoning Romantic movement, Mayer's work generally maintains a greater degree of objectivity and detailed observation, less focused on overt emotional drama, though his depictions of ruins certainly carry inherent romantic connotations for his audience. He predates the more intensely personal or politically charged Orientalism of the 19th century.

Collections and Continuing Relevance

Today, Luigi Mayer's original works are held in important collections worldwide. The British Museum in London houses a significant number of his drawings and the resulting prints. The Albertina Museum in Vienna also holds examples of his work. In Turkey, the Suna and İnan Kıraç Foundation's Pera Museum and the Istanbul Research Institute possess notable collections, highlighting his importance for Turkish cultural history. These institutions preserve the delicate watercolours and gouaches that formed the basis for the widely circulated prints.

The prints themselves are more widely distributed and can be found in numerous libraries and museum print rooms. Mayer's work continues to be studied for its artistic merit, its historical significance as a record of the late Ottoman world, and its role in shaping Western perceptions of the East. Exhibitions occasionally feature his work, bringing his meticulous views to new audiences.

Unanswered Questions

Despite the relative wealth of visual material, aspects of Luigi Mayer's life remain unclear. The precise motivations behind his deep engagement with Ottoman subjects, beyond the requirements of his patron, are not fully documented. Details of his personality and his own perspective on the cultures he depicted are largely inferred from his work rather than from personal writings. The circumstances surrounding the nearly decade-long gap between his departure from Constantinople with Ainslie and the beginning of the publication series also invite speculation. Was it purely the time needed for engraving and financing, or did other factors play a role? His relationship with Clara, while documented as collaborative, leaves room for further understanding of their individual contributions.

Conclusion

Luigi Mayer remains a pivotal, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the history of European art and its engagement with the wider world. As Sir Robert Ainslie's visual chronicler, he produced an unparalleled record of the Ottoman Empire and the Eastern Mediterranean at the cusp of the 19th century. His meticulous watercolours, brought to a wide public through aquatint engravings, satisfied and further stimulated Europe's growing fascination with the East. Combining topographical accuracy with artistic sensitivity, Mayer created works that are both beautiful objects and invaluable historical documents. He stands as a key early practitioner of Orientalist art, whose detailed and expansive views provided a foundational visual vocabulary for subsequent generations exploring the landscapes, antiquities, and cultures of the Near East. His legacy endures in the collections that preserve his work and in the ongoing study of the complex relationship between West and East that his art illuminates.