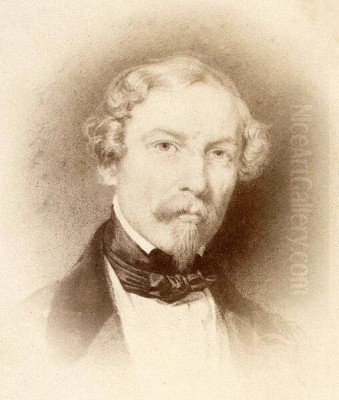

The 19th century was an era of profound European engagement with the wider world, marked by exploration, colonial expansion, and a burgeoning academic and popular interest in distant cultures. Within this context, the figure of Eugène Napoléon Flandin (1809-1889) emerges as a remarkable polymath: an accomplished painter, a dedicated archaeologist, a keen-eyed Orientalist, and even a participant in the political sphere. Born in Naples, Italy, but French by nationality and spirit, Flandin dedicated much of his life to documenting the historical and contemporary realities of the Near and Middle East, leaving behind a legacy of artworks and publications that continue to inform our understanding of these regions. His meticulous observations and artistic skill, particularly concerning Persia (modern-day Iran) and Mesopotamia, have cemented his place as a significant contributor to both art history and archaeological studies.

Early Impulses and the Allure of the East

While specific details about Eugène Flandin's earliest artistic training and his specific mentors remain somewhat elusive in comprehensive records, his development occurred within a vibrant French artistic milieu. The early to mid-19th century in France was a period of stylistic transition and exploration. The Neoclassicism championed by artists like Jacques-Louis David was ceding ground to the burgeoning Romantic movement, with figures such as Eugène Delacroix leading the charge with his dramatic and color-rich depictions, often inspired by his own travels to North Africa. This Romantic fascination with the "Orient"—a term then encompassing North Africa, the Middle East, and sometimes further afield—provided a powerful impetus for artists seeking new subjects and a departure from established European themes.

It was in this environment that Flandin's own inclinations towards the East were likely nurtured. His early career saw him engage with various artistic pursuits, but it was his expeditions that would come to define his most significant contributions. Before his seminal Persian journey, Flandin undertook explorations in Algeria. France's involvement in Algeria, beginning in 1830, opened up the region to French artists and scholars. Flandin seized this opportunity, traveling there to capture its landscapes, architectural marvels, and the daily life of its inhabitants. These early works, though perhaps less renowned than his Persian portfolio, were crucial in honing his skills in topographical accuracy and ethnographic observation, preparing him for the more extensive and demanding expeditions to come. His paintings and drawings from Algeria already showcased a keen eye for detail and an ability to convey the unique atmosphere of the places he visited.

The Landmark Persian Expedition with Pascal Coste

The most pivotal undertaking of Flandin's career was undoubtedly his mission to Persia, a journey he embarked upon between 1839 and 1841. This expedition was officially sanctioned by the French government, reflecting the strategic and academic interest France held in the region. For this ambitious project, Flandin was partnered with the talented architect Pascal-Xavier Coste (1787-1879). Coste, already an experienced traveler and draftsman who had worked extensively in Egypt for Muhammad Ali Pasha, brought architectural expertise that perfectly complemented Flandin's artistic and observational skills. Their shared objective was to create a comprehensive visual and textual record of Persia's ancient monuments and contemporary state.

Together, Flandin and Coste traversed vast swathes of Persia, enduring challenging conditions to reach remote historical sites. Their itinerary was extensive, covering key locations of immense historical and cultural significance. They meticulously documented the ruins of Persepolis, the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire, capturing its grand staircases, intricate reliefs, and towering columns. They explored Pasargadae, the first dynastic capital of the Achaemenid Empire and the site of Cyrus the Great's tomb. Their travels also took them to Isfahan, with its magnificent Safavid-era mosques and palaces; Shiraz, a city renowned for its poets and gardens; Ecbatana (modern Hamadan), an ancient Median and Achaemenid city; and the impressive rock reliefs at Bisitun (Behistun) and Taq-i Bostan. They also visited Kangavar, noted for its Anahita temple remains, and even sites in Mesopotamia, including the legendary Babylon.

Flandin's role was primarily to create drawings and paintings of the monuments, landscapes, and scenes of daily life, while Coste focused on architectural plans, elevations, and reconstructions. Their collaboration was synergistic, resulting in a body of work that was both artistically compelling and scientifically valuable. Flandin’s drawings were not mere picturesque renderings; they were precise records, often including measurements and detailed observations of inscriptions and decorative elements. He captured not only the grandeur of the ancient sites but also their state of preservation, providing invaluable data for future archaeological work. His depictions of contemporary Persian life, including urban scenes, portraits, and costumes, added another layer of richness to their documentation.

Voyage en Perse: A Monumental Publication

The fruits of Flandin and Coste's arduous journey were compiled into the monumental publication Voyage en Perse (Journey to Persia). The primary volumes illustrating ancient Persia, Perse ancienne, and modern Persia, Perse moderne, were published with Flandin's illustrations and Coste's architectural drawings. The main textual and illustrative work appeared in several volumes, with the most comprehensive edition often cited as being published around 1851 in Paris. This lavishly illustrated work was a landmark in Orientalist scholarship and art. It comprised detailed textual descriptions alongside hundreds of lithographs based on Flandin's drawings and Coste's plans.

Voyage en Perse was divided into sections covering ancient monuments, modern Persian architecture, and scenes of contemporary life. Flandin's contributions were particularly notable for their artistic quality and documentary precision. His illustrations of Persepolis, for example, brought the ancient capital to life for a European audience that had previously only read about it or seen less accurate depictions. He meticulously rendered the cuneiform inscriptions, the reliefs of tribute bearers, and the architectural details, often working under difficult conditions. His landscapes captured the dramatic scenery of the Iranian plateau, while his genre scenes offered glimpses into the customs and attire of 19th-century Persians.

The publication of Voyage en Perse was a significant event. It provided an unprecedented visual record of a region that was still relatively inaccessible to Europeans. It became an essential reference work for archaeologists, historians, and art historians, and its illustrations were widely admired for their beauty and accuracy. The work solidified Flandin's reputation as a leading Orientalist artist and a meticulous documentarian. It also served to further stimulate European interest in Persian history and culture, influencing other artists and scholars, such as the later traveler and photographer Jane Dieulafoy, who also documented Persian sites with her husband Marcel Dieulafoy.

Archaeological Endeavors: Khorsabad and Beyond

Flandin's passion for the ancient world extended beyond documentation to active participation in archaeological discovery. Following his Persian expedition, he became involved in another groundbreaking project in Mesopotamia. In 1843, he joined Paul-Émile Botta (1802-1870), the French consul in Mosul, who had begun excavating the site of Khorsabad, ancient Dur-Sharrukin, the capital of the Assyrian king Sargon II. Botta had initially been searching for Nineveh but stumbled upon the magnificent remains of Sargon's palace.

Flandin's artistic skills proved invaluable at Khorsabad. He was tasked with meticulously drawing the colossal winged bulls (lamassu), intricate reliefs, and other artifacts as they were unearthed. His drawings were crucial for several reasons: they provided a record of the objects in situ before any potential damage during excavation or transport; they captured details that might be lost over time; and they helped in understanding the layout and decoration of the palace. He documented the massive stone slabs depicting scenes of royal hunts, battles, and ceremonial processions, including notable reliefs showing the transport of timber, which provided insights into Assyrian logistics and technology.

The collaboration between Botta, the excavator, and Flandin, the artist-archaeologist, was a model for its time. Flandin’s drawings from Khorsabad were published in Monuments de Ninive (Monuments of Nineveh), a major work edited by Botta, which, despite its title (Nineveh was actually excavated later by Austen Henry Layard), primarily showcased the finds from Khorsabad. These illustrations, like those from Persia, were characterized by their precision and artistic sensitivity, contributing significantly to the nascent field of Assyriology. Flandin's work helped to bring the splendors of the ancient Assyrian civilization to the attention of the European public and scholarly community, much like Layard's own illustrated accounts of his discoveries at Nimrud and Nineveh did for the British audience.

Flandin's Artistic Style: Orientalism and Romanticism

Eugène Flandin's artistic style is firmly rooted in the 19th-century European tradition of Orientalism, yet it also bears the hallmarks of Romanticism and a commitment to scientific accuracy. His work is characterized by a remarkable attention to detail, a skill essential for his archaeological and topographical drawings. Whether depicting the intricate patterns of a Persian tile or the complex iconography of an Assyrian relief, Flandin's line work is precise and controlled. This meticulousness did not, however, result in dry or sterile images.

There is a distinct Romantic sensibility in Flandin's art. He was adept at capturing the atmosphere of the places he visited, often imbuing his scenes of ancient ruins with a sense of grandeur and melancholic beauty. The play of light and shadow in his compositions, the dramatic perspectives, and the inclusion of human figures to provide scale and context all contribute to this Romantic appeal. This was a common trait among Orientalist painters like Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps or Prosper Marilhat, who also sought to convey the exotic allure and historical weight of the East.

Flandin’s palette, particularly in his finished paintings (as distinct from his on-site sketches and drawings which were often monochrome or lightly washed), reflected the vibrant colors he encountered, though often filtered through the European aesthetic conventions of the time. His depictions of people, while ethnographic in intent, sometimes carried the idealized or exoticized traits common in Orientalist art. However, his primary focus, especially in his published works, was on accurate representation, which set him apart from artists who prioritized purely imaginative or sensationalized Orientalist fantasies, such as some of the harem scenes popularised by painters like Jean-Léon Gérôme or even Ingres with his "La Grande Odalisque." Flandin's work aimed to inform as much as to delight, bridging the gap between art and science. His military paintings, also mentioned as part of his oeuvre, likely depicted scenes related to French colonial campaigns or historical reconstructions, executed with similar attention to detail.

Other Travels and Works

While Persia and Mesopotamia were central to Flandin's fame, his travels and artistic output were not limited to these regions. As mentioned, his early experiences in Algeria provided a foundation for his later expeditions. He continued to produce works based on his North African experiences throughout his career. Furthermore, Flandin also traveled to other parts of the Ottoman Empire, including Turkey. He is known to have created panoramic views and detailed studies of Turkish cities, such as Constantinople (Istanbul) and Antalya. These works, like his Persian and Mesopotamian drawings, are valuable for their historical and topographical information, capturing these urban landscapes before significant modern transformations.

These diverse undertakings underscore Flandin's restless curiosity and his dedication to documenting the wider "Orient." His ability to adapt his artistic skills to different environments and subject matter—from the sun-baked ruins of Persepolis to the bustling streets of Algiers or the coastal vistas of Anatolia—speaks to his versatility. Each journey added to his visual repertoire and contributed to the European understanding, however filtered, of these cultures. His work can be seen in dialogue with other traveling artists of the period, such as the British painter David Roberts, whose lithographs of Egypt and the Holy Land were immensely popular, or French contemporaries like Horace Vernet, known for his battle scenes and North African subjects.

Flandin and His Contemporaries

Eugène Flandin operated within a dynamic network of artists, scholars, and explorers. His most significant professional relationships were collaborative, most notably with Pascal Coste on the Persian expedition and with Paul-Émile Botta at Khorsabad. These partnerships were crucial to the success of their respective missions, combining diverse skill sets for a common goal. The monumental publications resulting from these collaborations set a high standard for archaeological and ethnographic documentation.

Beyond these direct collaborations, Flandin was a contemporary of many other prominent figures in the Orientalist movement and 19th-century art. While Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) was a towering figure whose Moroccan journey in 1832 had a profound impact on French Orientalism, Flandin’s approach was generally more documentary than Delacroix's expressive and color-driven style. Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), though younger, became one of the most famous academic Orientalist painters, known for his highly detailed and often meticulously researched, if sometimes romanticized, scenes. Théodore Chassériau (1819-1856), a student of Ingres like Jean-Hippolyte Flandrin (no direct relation to Eugène, despite the similar name), also explored Orientalist themes with a distinctive blend of classicism and romanticism.

The field of archaeological illustration was also populated by skilled artists. The British explorer Austen Henry Layard, for instance, employed artists like Frederick Charles Cooper to document his finds at Nimrud and Nineveh. The meticulous work of these artists was essential for disseminating knowledge about ancient civilizations before the widespread use of photography in archaeological fieldwork. Flandin's contribution stands out for his dual role as both a skilled artist and an active participant in the research and documentation process. One might also consider figures like Jules Laurens (1825-1901), another French artist who travelled to Persia and Turkey, producing a significant body of work, though perhaps with a different emphasis than Flandin's archaeologically-focused output.

Legacy and Enduring Impact

Eugène Napoléon Flandin's legacy is multifaceted. As an artist, he produced a significant body of work characterized by technical skill, observational acuity, and a Romantic sensibility. His drawings and paintings are not only aesthetically pleasing but also serve as invaluable historical documents. His depictions of ancient monuments, often captured before further degradation or alteration, are crucial for art historians and archaeologists studying these sites. The precision of his renderings of inscriptions and architectural details has aided in their interpretation and understanding.

As an archaeologist and explorer, Flandin made tangible contributions to the discovery and documentation of ancient Near Eastern civilizations. His work with Botta at Khorsabad was instrumental in bringing Assyrian art and architecture to global attention. His comprehensive survey of Persian sites with Coste provided a foundational visual record that informed subsequent research for decades. Voyage en Perse and Monuments de Ninive remain landmark publications, testaments to the ambition and dedication of these 19th-century scholar-adventurers.

Flandin's work also played a role in shaping European perceptions of the Orient. While Orientalism as a broader cultural phenomenon has been critiqued for its colonial undertones and tendency to exoticize or stereotype, Flandin's contributions, particularly his archaeological work, were grounded in a genuine effort to record and understand. His images helped to foster a greater appreciation for the rich cultural heritage of Persia and Mesopotamia, contributing to the development of museums and collections dedicated to these civilizations across Europe, including the Louvre which received many of the Khorsabad finds.

A Chronicler for His Time and Ours

Eugène Napoléon Flandin was a man of his time, driven by the 19th-century European thirst for knowledge and adventure in the East. His career as a painter, archaeologist, Orientalist, and traveler resulted in a rich and varied body of work that continues to be of immense value. His meticulous drawings and paintings, particularly those from Persia and Khorsabad, stand as a testament to his skill, dedication, and his profound engagement with the cultures he documented.

While the era of grand Orientalist expeditions has passed, and the methods of documentation have evolved with technologies like photography and digital imaging, Flandin's work endures. His art provides a unique window into the past, capturing not only the physical appearance of monuments and landscapes but also something of the spirit of discovery that animated his endeavors. He remains a key figure for anyone studying the art and archaeology of the Near East, or the fascinating history of European encounters with the Oriental world. His contributions ensure his place among the important chroniclers of civilizations, whose visual records have outlasted empires and continue to speak to us across the centuries.