Magnus Enckell (1870-1925) stands as one of Finland's most pivotal and intriguing painters, a leading figure during the Golden Age of Finnish Art and a crucial conduit for modern European artistic currents into the Nordic region. His journey from a restrained, almost ascetic Symbolism to a vibrant, color-drenched Post-Impressionism charts a fascinating evolution, reflecting both personal artistic exploration and the broader shifts in the European art world at the turn of the 20th century. Enckell was not merely a painter; he was an organizer, a cultural influencer, and an artist whose work delved into profound themes of human existence, spirituality, and sensuality.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Finland

Born Knut Magnus Enckell on November 9, 1870, in Hamina, a small town in eastern Finland, he was the youngest of six sons in the family of Carl Wilhelm Enckell, a clergyman, and Alexandra Enckell. This upbringing within a vicarage likely instilled in him a certain intellectual curiosity and perhaps an early exposure to theological and philosophical questions that would later subtly permeate his art. His initial artistic inclinations led him to Helsinki in 1889, where he enrolled at the drawing school of the Finnish Art Society.

However, the formal academic environment there did not entirely satisfy his burgeoning artistic spirit. Enckell soon left the school to pursue private studies under Gunnar Berndtson, a respected Finnish painter known for his elegant portraits and genre scenes, who had himself studied in Paris under masters like Jean-Léon Gérôme. This mentorship under Berndtson provided Enckell with a solid grounding in traditional techniques, but his gaze was already turning towards the more avant-garde developments unfolding in the art capital of the world: Paris.

Parisian Sojourn and Symbolist Immersion

In 1891, Enckell made his first transformative journey to Paris. He enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian, a popular alternative to the more conservative École des Beaux-Arts, which attracted students from across the globe. There, he studied under the tutelage of renowned academic painters Jules-Joseph Lefebvre, celebrated for his idealized female nudes and portraits, and Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, known for his Orientalist scenes and large-scale historical paintings. While these instructors provided rigorous academic training, it was the broader artistic atmosphere of Paris that truly captivated Enckell.

This was a period when Symbolism was at its zenith, reacting against the perceived superficiality of Naturalism and Impressionism. Symbolist artists sought to express ideas, emotions, and spiritual truths through suggestive imagery, often drawing on mythology, dreams, and esoteric philosophies. Enckell was profoundly influenced by this movement. He particularly admired the work of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, whose monumental, dream-like murals with their simplified forms, muted colors, and serene, allegorical figures resonated deeply with Enckell's own introspective temperament. Another significant influence was Joséphin Péladan, the eccentric writer and Rosicrucian who organized the Symbolist Salon de la Rose+Croix, exhibitions that Enckell would have been aware of and which championed art with mystical and spiritual themes.

The Rise of a Symbolist Master

Returning to Finland, Enckell began to forge his unique Symbolist style. His early works from this period are characterized by a restrained, almost ascetic palette, often dominated by grays, blues, and ochres, and a focus on simplified forms and ethereal figures. He sought to convey an inner, spiritual reality rather than a mere depiction of the external world. His figures often appear isolated, contemplative, and imbued with a sense of melancholy or quiet introspection.

One of his most iconic early Symbolist paintings is The Awakening (1894). This work depicts a nude youth, eyes closed, seemingly emerging from a slumber or a trance-like state, set against a stark, minimalist background. The painting eschews overt narrative, instead evoking a sense of spiritual or intellectual awakening, a common Symbolist theme. The androgynous quality of the figure and the overall asceticism of the composition are hallmarks of Enckell's early Symbolist phase.

Another significant work from this period is Boy with Skull (1898), which directly engages with the memento mori tradition, reminding viewers of the transience of life and the inevitability of death. The starkness of the composition and the introspective mood are characteristic of his Symbolist output. During this time, Enckell was part of a vibrant Finnish art scene that included other prominent Symbolists like Akseli Gallen-Kallela, whose epic Kalevala-inspired works defined a national Romanticism, and Hugo Simberg, known for his macabre and whimsical imagery. While sharing Symbolist inclinations, Enckell's approach was often more personal and less overtly nationalistic than Gallen-Kallela's.

Thematic Explorations: Sensuality, Spirituality, and Mythology

Enckell's oeuvre is rich with diverse themes, but his exploration of the human form, particularly the nude, is central to his artistic identity. His depictions of both male and female nudes often carry a distinct erotic and sensual charge, which was considered quite bold for the conservative Finnish society of his time. Works like Boys on the Shore (1910) showcase his interest in the youthful male form, rendered with a sensitivity that has led many scholars and contemporary accounts to suggest Enckell was homosexual. While never officially confirmed by the artist himself, this aspect of his identity is often discussed in relation to the homoerotic undertones present in some of his works. His willingness to explore such themes openly, even if subtly, marked him as a progressive figure.

Beyond the sensual, Enckell's art frequently touched upon spiritual and mythological subjects. His religious upbringing may have informed his interest in Christian iconography, though he often reinterpreted these themes through a Symbolist lens, focusing on their universal spiritual significance rather than strict dogma. His engagement with classical mythology also provided a rich source of inspiration, allowing him to explore timeless human emotions and archetypes.

A Shift Towards Color: Post-Impressionism and the Septem Group

A pivotal moment in Enckell's artistic development occurred around 1902, following travels to Italy. The vibrant light and rich artistic heritage of Italy, particularly the works of the Renaissance masters and the sun-drenched landscapes, had a profound impact on him. This experience, coupled with his increasing exposure to Post-Impressionist currents emanating from France – the works of artists like Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, and Georges Seurat – led to a significant shift in his style.

Enckell began to embrace a much brighter, more luminous palette, moving away from the muted tones of his earlier Symbolist phase. His brushwork became freer and more expressive, and he started to experiment with the optical effects of color, characteristic of Neo-Impressionism and Pointillism. This transformation was not an abandonment of Symbolism but rather an integration of its spiritual depth with a newfound celebration of light and color.

This stylistic evolution culminated in his co-founding of the "Septem" group in 1912. This influential artists' collective, which Enckell led, included other prominent Finnish artists such as Verner Thomé, Ellen Thesleff, Alfred William Finch (an Anglo-Belgian artist who played a key role in introducing Neo-Impressionism to Finland), Mikko Oinonen, Juho Rissanen, and Yrjö Ollila. The Septem group championed "pure painting," emphasizing the importance of color and light, and sought to bring Finnish art into closer dialogue with contemporary European modernism, particularly French Post-Impressionism. Their exhibitions were instrumental in modernizing the Finnish art scene.

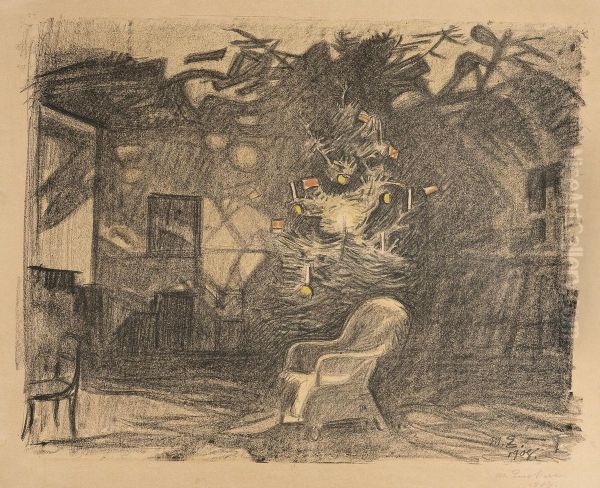

A work like Christmas Tree (1908), with its vibrant colors and joyful atmosphere, exemplifies this later phase, though it predates the formal establishment of Septem, it shows the direction his art was taking. His portraits and landscapes from this period are characterized by a heightened chromatic intensity and a more optimistic mood compared to his earlier works.

Monumental Works and Public Commissions

Magnus Enckell was not confined to easel painting; he also undertook significant public commissions, most notably the altarpiece for Tampere Cathedral. Consecrated in 1907, Tampere Cathedral is a masterpiece of Finnish National Romantic architecture, designed by Lars Sonck, and features extensive artwork by prominent artists of the Golden Age, including Hugo Simberg, who painted the haunting frescoes.

Enckell was commissioned to create the massive altarpiece, titled The Resurrection. Measuring over ten meters wide and four meters high, this monumental fresco depicts figures of various races rising towards a celestial light, symbolizing the universality of resurrection and hope. The work is a powerful synthesis of Enckell's Symbolist sensibilities and his later, more colorful style. The figures are rendered with a certain idealism, and the overall composition is imbued with a profound spiritual atmosphere. This commission solidified Enckell's reputation as one of Finland's foremost artists, capable of handling large-scale, thematically complex projects.

Enckell the Organizer and Cultural Figure

Beyond his personal artistic production, Enckell played a vital role in the organization and promotion of Finnish art. He served as the chairman of the Finnish Artists' Association from 1915 to 1918, a position of considerable influence within the national art community. In this capacity, and through his involvement with groups like Septem, he was instrumental in organizing numerous art exhibitions, both within Finland and internationally.

He helped curate Finnish art exhibitions in cities like Paris and Berlin, introducing the unique character of Finnish art to a wider European audience. Conversely, he was also involved in bringing international art to Finland, such as the significant Franco-Belgian exhibition held at the Ateneum in Helsinki in 1904, which showcased works by artists like Paul Signac and Théo van Rysselberghe, further exposing Finnish artists and the public to Neo-Impressionist and other modern movements. These activities were crucial for fostering a dynamic artistic environment in Finland and ensuring its connection to broader European trends.

Personal Life and Artistic Milieu

Enckell's personal life was intertwined with his artistic pursuits. He frequently spent summers on Suursaari (Hogland), an island in the Gulf of Finland, which provided inspiration for many of his landscapes. He also purchased land in Kuorsalo, another coastal location, where he built a studio, seeking tranquility and a close connection to nature for his creative work.

He maintained close friendships with fellow artists, including his Septem colleagues Verner Thomé and Ellen Thesleff. His intellectual interests extended beyond painting; he was reportedly keen on music, theatre, and literature, and moved within Finland's cultural circles, interacting with writers and other prominent figures of the era. The discussions around his sexuality, often inferred from the sensitive and sometimes homoerotic portrayal of male figures in his art, add another layer to his persona, suggesting a man who navigated his personal identity with a degree of courage in a society that was not always tolerant.

Later Years and Evolving Style

In his later years, Enckell continued to evolve. There is evidence of an increasing interest in classical forms and a more structured, almost monumental approach to composition, perhaps a synthesis of his early Symbolist austerity with the lessons learned from Italian art and his later colorism. He continued to explore themes of human spirituality and the beauty of the natural world, always with a refined aesthetic sensibility.

His commitment to art remained unwavering until his death. Magnus Enckell passed away in Stockholm, Sweden, on November 27, 1925, at the age of 55. He was buried in his native Finland, leaving behind a rich and diverse body of work.

Legacy and Posthumous Recognition

Magnus Enckell's legacy is multifaceted. He is celebrated as a pioneer of Finnish Symbolism, an artist who brought a unique spiritual depth and psychological insight to his work. His later embrace of color and light, and his role in founding the Septem group, mark him as a key figure in the advent of modernism in Finnish art. He stands alongside other giants of the Finnish Golden Age, such as Helene Schjerfbeck, known for her increasingly abstract self-portraits and still lifes; Eero Järnefelt, famed for his realistic portraits and landscapes; and Pekka Halonen, celebrated for his depictions of Finnish winter landscapes and folk life.

His works are housed in major Finnish art museums, including the Ateneum Art Museum in Helsinki, which holds a significant collection. Posthumous exhibitions have continued to affirm his importance. Notably, in 2020, the Ateneum Art Museum mounted a major retrospective to celebrate the 150th anniversary of his birth, showcasing over one hundred works and spanning his entire fifty-year career. Such exhibitions allow contemporary audiences to appreciate the breadth and depth of his artistic vision, from his early, introspective Symbolist pieces to his later, more vibrant Post-Impressionist works.

Conclusion: An Enduring Influence

Magnus Enckell remains an enduring figure in the history of Finnish and Nordic art. His ability to synthesize international artistic currents with a deeply personal vision resulted in a body of work that is both historically significant and aesthetically compelling. From the ethereal figures of his Symbolist period to the luminous canvases of his Septem era, Enckell consistently sought to express profound human experiences through the language of paint. His explorations of spirituality, sensuality, and the pure qualities of color and light continue to resonate, securing his place as a visionary artist who significantly shaped the course of modern art in Finland. His life and work serve as a testament to the power of art to explore the innermost recesses of the human spirit and to reflect the changing cultural landscapes of its time.