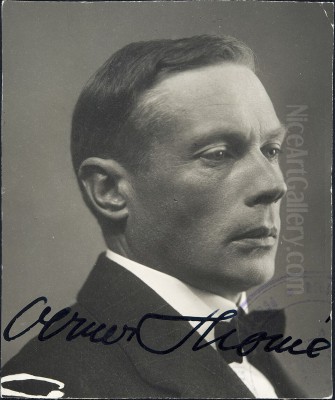

Verner Thome (1878–1953) stands as a significant figure in the landscape of Finnish art, particularly celebrated for his adept use of color and light, and his pivotal role in introducing modern European artistic currents to Finland. His career spanned a transformative period in art history, witnessing the shift from National Romanticism to various forms of modernism. Thome was not merely a passive observer of these changes; he was an active participant, an innovator, and a co-founder of one of Finland's most influential early 20th-century art groups.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Alajärvi, Finland, in 1878, Verner Thome's early life set the stage for an artistic journey that would see him explore the cutting edge of European painting. His father's profession as a forester may have instilled in him an early appreciation for nature and landscape, themes that would recur throughout his oeuvre. Finland, during Thome's formative years, was an Grand Duchy within the Russian Empire, experiencing a burgeoning sense of national identity, often expressed through art and culture. The dominant artistic style was National Romanticism, championed by figures like Akseli Gallen-Kallela, which focused on Finnish folklore, mythology, and the stark beauty of the Finnish landscape, often rendered in a symbolic and somewhat somber palette.

Thome's formal artistic education began at the Finnish Art Society's drawing school in Helsinki (now the Academy of Fine Arts), a common starting point for aspiring Finnish artists. However, like many of his ambitious contemporaries, he understood the necessity of seeking further training and exposure abroad. The art capitals of Europe, particularly Munich and Paris, beckoned with their established academies, vibrant avant-garde scenes, and the promise of direct engagement with the latest artistic developments.

European Sojourns and Influences

Thome's travels and studies in Europe were crucial in shaping his artistic vision. He spent time in Munich, which at the turn of the century was a significant art center, known for its academic tradition but also for the Secession movement, which challenged established norms. However, it was Paris that would prove most transformative. The French capital was the undisputed epicenter of the art world, a crucible of innovation where Impressionism had already revolutionized painting, and Post-Impressionist movements like Neo-Impressionism (Pointillism/Divisionism) and Fauvism were either established or emerging.

In Paris, Thome would have encountered the works of Impressionist masters such as Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, whose emphasis on capturing fleeting moments of light and atmosphere through broken brushwork and a brighter palette was a revelation. He was also exposed to the more systematic approach of Neo-Impressionists like Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. Their theories on color, optics, and the meticulous application of dots or small strokes of pure color to create vibrant, luminous surfaces, profoundly influenced a generation of artists, including Thome. The emphasis on light and its effects, and the liberation of color from purely descriptive purposes, became central to his developing style. He also studied under Eugène Carrière, known for his atmospheric, often monochromatic, Symbolist works, which might have contributed to Thome's sensitivity to mood and atmosphere, even as he embraced a more color-centric approach.

The Emergence of a Distinctive Style: Neo-Impressionism and Contre-Jour

Returning to Finland, Thome began to synthesize these international influences into a personal style. He became particularly known for his adaptation of Neo-Impressionist techniques. While not always adhering strictly to the pointillist method of Seurat, Thome embraced the principle of optical mixing and the use of pure, bright colors to convey the brilliance of light. His brushwork could range from small dabs to more elongated strokes, but the overall effect was one of vibrancy and luminosity.

A characteristic feature of Thome's work, as noted, is his skilled use of the contre-jour (against the light) technique. This involves placing the main subject between the viewer and the light source, often resulting in silhouettes or figures haloed by light. It's a challenging technique, as direct sunlight can overwhelm the scene, but Thome mastered it to create dramatic and evocative effects, particularly in his depictions of figures in landscapes. This technique allowed him to explore the interplay of light and shadow, and the way light dissolves and defines forms.

His subject matter often revolved around landscapes, coastal scenes, and figures in outdoor settings, reflecting both his Finnish roots and the Impressionist preoccupation with plein air painting and scenes of leisure. Works from this period showcase his refined color sense and his ability to capture the specific qualities of Nordic light, which can be both clear and diffuse.

Representative Works: Capturing Light and Life

While a comprehensive list of all his major works is extensive, certain paintings stand out as exemplars of his style and concerns. Bathing Boys (Pojkar i badet), painted around 1910-1911, is perhaps one of his most iconic works and clearly demonstrates his Neo-Impressionist leanings and mastery of light. The painting depicts young figures by the water, their forms rendered with dabs of color that shimmer and blend in the viewer's eye. The play of sunlight on the water and the figures, the vibrant blues, greens, and flesh tones, all contribute to a sense of idyllic summer leisure and the dazzling effect of light. This work, sometimes referred to as Bathing Girls in some contexts, is a prime example of his engagement with modern French painting.

Another notable work is In the Park (Kaisaniemi Park) (Puistossa (Kaisaniemen puisto)) from 1906. This painting captures a serene moment in one of Helsinki's beloved parks, again demonstrating Thome's ability to translate the effects of light filtering through leaves and dappling the ground into a vibrant tapestry of color. His landscapes, whether from Finland or his travels in Italy and the South of France, consistently reveal his preoccupation with light and atmosphere, rendered with a sophisticated understanding of color theory. View from Alppi Street (Näkymä Alppikadulta), 1903, shows an earlier phase, perhaps less overtly Neo-Impressionist but already demonstrating a keen interest in urban light and atmosphere.

The Septem Group: A Collective Push for Modernism

Verner Thome's most significant contribution to Finnish art history, beyond his individual artistic achievements, was his role as a co-founder of the Septem group. Established formally with their first exhibition in 1912, Septem was a collective of artists who sought to champion a more colorist, light-filled approach to painting, directly inspired by French Impressionism and Neo-Impressionism. The group's name, meaning "seven" in Latin, referred to its core members, though the lineup could fluctuate slightly.

The driving force behind Septem was Magnus Enckell (1870–1925), a prominent Finnish Symbolist painter who, after a period of more somber, Symbolist works, had himself embraced a brighter, more Impressionistic palette. Enckell, Thome, and Ellen Thesleff (1869–1954)—another pioneering Finnish modernist known for her ethereal, color-rich paintings—were central figures in the group's formation and ideology. Other key members included Alfred William Finch (1854–1930), a Belgian-English artist who had settled in Finland and was a crucial link to Neo-Impressionism (having known Seurat), Yrjö Ollila (1887–1932), and Mikko Oinonen (1883–1956). Juho Rissanen (1873–1950), known for his powerful depictions of Finnish peasant life, was also associated with the group for a period.

The Septem group's mission was, in part, a reaction against what they perceived as the prevailing darkness and conservatism in Finnish art. While National Romanticism had played a vital role in forging a Finnish cultural identity, by the early 20th century, younger artists felt the need for new forms of expression, for a greater emphasis on purely painterly qualities – color, light, and form – rather than narrative or nationalistic content. Septem advocated for "pure painting" and the importance of color as an expressive element in its own right. Their exhibitions were intended to introduce these modern principles to the Finnish public and to challenge the established artistic order.

Magnus Enckell, with his established reputation, often acted as the group's leader and spokesperson. He was instrumental in organizing exhibitions, including not only the Septem shows but also broader showcases of Finnish art abroad, such as in St. Petersburg in 1912, and later in Berlin and Paris. These efforts helped to raise the international profile of Finnish art and to connect Finnish artists with broader European trends. Verner Thome was an integral part of this movement, his own work serving as a prime example of the aesthetic ideals Septem championed.

Thome's Unique Voice within Septem

Within the Septem group, while all members shared a common interest in color and light, each artist maintained their individual style. Thome's contribution was characterized by a refined elegance and a lyrical quality. His application of Neo-Impressionist principles was often more subtle and less dogmatic than that of some of its French originators. He skillfully adapted these techniques to depict the unique character of Finnish landscapes and light, which differs significantly from the light of the Mediterranean or southern France that so captivated many Impressionists.

His palette, while bright, was often nuanced and harmonious, avoiding the sometimes jarring juxtapositions of color seen in Fauvism, another contemporary movement. There was a certain classicism and balance in his compositions, even as he embraced modern techniques. His figures, often depicted in moments of quiet contemplation or leisure, possess a gentle grace. This distinguishes his work from, for example, the more robust, earthy figures of Juho Rissanen or the more overtly Symbolist undertones that could still be found in some of Enckell's work. Ellen Thesleff, by contrast, often pushed towards a more abstract and intensely personal expression of color and light.

Interactions with the Broader Finnish Art Scene

The emergence of Septem and its advocacy for French-inspired modernism did not occur in a vacuum. It was part of a broader wave of change in Finnish art. While figures like Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Pekka Halonen (1865-1933), and Eero Järnefelt (1863-1937) had established National Romanticism as a dominant force, a new generation was seeking different paths. Hugo Simberg (1873–1917), another major Finnish Symbolist, created a unique and deeply personal iconography, while Helene Schjerfbeck (1862–1946), one of Finland's most celebrated artists, was developing her own highly individual modernist style, characterized by simplification, subtle color harmonies, and psychological depth.

The Septem group, therefore, represented one significant strand of modernism in Finland. Their emphasis on color and light offered a distinct alternative to the narrative and symbolic concerns of National Romanticism and the introspective Symbolism of artists like Simberg. While their approach was initially met with some resistance from more conservative critics, who perhaps found their bright colors too "foreign" or their subject matter lacking in nationalistic gravitas, Septem played a crucial role in broadening the horizons of Finnish art and paving the way for subsequent modernist developments.

Later Career and Artistic Evolution

Throughout his career, Verner Thome continued to paint with a dedication to his core artistic principles. While the initial impact of Neo-Impressionism remained a foundation of his style, his work evolved. He traveled, including to Italy, and these experiences often found their way into his paintings, enriching his palette and subject matter. His later works might show a somewhat looser brushwork or a greater emphasis on atmospheric effects, but the consistent thread is his profound engagement with light and color.

He participated in numerous exhibitions both in Finland and internationally, contributing to the growing recognition of Finnish art. He was a respected figure in the Finnish art community, not only for his artistic talent but also for his role in fostering a more international outlook among Finnish artists. The legacy of the Septem group, and Thome's part in it, was to firmly establish colorism and a modern, painterly approach within the Finnish artistic tradition.

It is important to note that the anecdote concerning Verner Thome and Ota Benga appears to be a misattribution. The individual associated with Ota Benga was Samuel Phillips Verner, an American explorer and missionary. There is no credible art historical evidence linking Verner Thome, the Finnish painter, to this episode. Such confusions can sometimes arise with similar names across different fields and nationalities.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Verner Thome passed away in 1953, leaving behind a significant body of work and an important legacy. His paintings are held in major Finnish museum collections, including the Ateneum Art Museum in Helsinki, and are prized for their beauty, technical skill, and historical importance. He is remembered as one of the key figures who helped to modernize Finnish art, steering it away from a purely nationalistic focus towards a more international, aesthetically driven approach.

His influence, and that of the Septem group, can be seen in the subsequent generations of Finnish painters who continued to explore the expressive possibilities of color and light. By championing the principles of French Impressionism and Neo-Impressionism, Thome and his colleagues opened up new avenues for artistic expression in Finland. They demonstrated that modern European artistic languages could be adapted to reflect the unique cultural and natural environment of Finland.

In conclusion, Verner Thome was more than just a skilled painter; he was a vital conduit for modernist ideas in Finland. His dedication to capturing the ephemeral qualities of light, his sophisticated use of color, and his role in the influential Septem group secure his place as a pivotal artist in the narrative of Finnish art. His works continue to delight viewers with their luminous beauty and stand as a testament to a period of vibrant artistic exchange and innovation. His art reminds us of the power of light and color to not only describe the world but also to evoke emotion and create enduring aesthetic experiences.