Manuel Robbe stands as a significant yet sometimes overlooked figure in the vibrant art world of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century Paris. A master printmaker, he navigated the currents of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and the burgeoning Art Nouveau movement, carving out a unique niche with his technically brilliant and aesthetically sensitive color aquatints. His work captures the essence of the Belle Époque, particularly its women, with a grace and intimacy that continues to resonate.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Paris in 1872, Manuel Robbe grew up in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune, a period of reconstruction and burgeoning modernity in the French capital. His initial education took place at the prestigious Lycée Condorcet, known for nurturing many French intellectuals and artists. It was here, and possibly through early private lessons, that his artistic inclinations began to surface.

Seeking formal training, Robbe enrolled at the Académie Julian, a famous private art school that served as a more liberal alternative to the official École des Beaux-Arts. The Académie Julian attracted students from around the world and was known for its progressive atmosphere, allowing artists like Robbe to experiment and develop their individual styles. Among his early mentors was the artist Louis Legrand, himself a notable painter and printmaker known for his depictions of modern Parisian life, particularly dancers and women of the demimonde, often compared to the work of Edgar Degas and Félicien Rops.

Robbe's artistic journey initially involved painting, but he soon gravitated towards the graphic arts. He explored lithography and poster design, media that were exploding in popularity during the 1890s thanks to artists like Jules Chéret and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. However, his true calling lay in intaglio printmaking. He further honed his skills at the École des Beaux-Arts, specifically focusing on the intricate techniques of etching and aquatint.

A pivotal figure in Robbe's development as a printmaker was Eugène Delâtre. Delâtre was not just an accomplished etcher himself but also a master printer whose workshop on Rue Lepic in Montmartre was a hub for artists exploring color printmaking. Delâtre printed works for luminaries such as Mary Cassatt, Camille Pissarro, and Auguste Renoir. Under Delâtre's guidance, Robbe mastered the complexities of etching and, crucially, the nuances of color aquatint, a medium he would make distinctively his own.

The Rise of a Printmaker

By the mid-1890s, Manuel Robbe had established himself as a promising printmaker. This period coincided with a significant revival of interest in original, artistic printmaking in France and across Europe. Artists sought to elevate printmaking beyond mere reproduction, exploring its expressive potential. Color printmaking, in particular, saw remarkable innovation, partly fueled by the influence of Japanese Ukiyo-e woodblock prints (Japonisme), which captivated artists like Degas, Cassatt, and Henri Rivière with their bold designs and flat color planes.

Robbe, however, primarily focused on the intaglio process, particularly aquatint, to achieve his color effects. Around 1895, he emerged as a pioneer in color etching and aquatint. He began exhibiting his works regularly, gaining recognition for his technical skill and the appealing nature of his subjects. His prints stood out for their soft, painterly qualities, a stark contrast to the bolder lines often seen in lithography or woodcut.

His association with leading print publishers and dealers, such as Edmond Sagot and Georges Petit in Paris, helped disseminate his work to a growing audience of collectors. These dealers played a crucial role in promoting the etching revival, commissioning editions from artists and organizing exhibitions that showcased the best contemporary printmaking. Robbe's prints found favor for their blend of modern subjects and technical refinement.

Mastery of Technique: Aquatint and Innovation

Manuel Robbe's reputation rests significantly on his mastery and innovative use of the aquatint process, especially in color. Aquatint involves etching tones rather than lines onto a metal plate (usually copper or zinc) by using powdered resin to create a porous ground. When bitten by acid, this creates a textured surface that holds ink, yielding areas of flat or subtly modulated tone when printed. Robbe excelled at manipulating this process to achieve exceptionally soft, velvety textures and delicate atmospheric effects.

His most notable technical contribution was his sophisticated use of printing "à la poupée" (with the doll). This technique allowed him to apply multiple colors to a single plate before printing. Using small pads or dabbers (poupées), he would carefully ink different areas of the plate with different colors. This required immense skill and precision, as the colors needed to be blended subtly on the plate to achieve the desired effect without appearing harsh or distinct. Printing à la poupée enabled Robbe to create rich, multi-hued images from a single pass through the press, giving his prints a unique luminosity and depth often compared to pastels or watercolors.

Robbe is also credited with experimenting extensively with, and perhaps even refining or popularizing, the "sugar-lift" or "lift-ground" aquatint technique (sucre levé). In this process, the artist draws directly onto the plate with a brush using a mixture of sugar syrup and ink or gouache. Once dry, the plate is coated with a liquid etching ground and immersed in water. The sugar swells and dissolves, lifting the ground above it and exposing the metal plate where the drawing was made. These exposed areas can then be treated with aquatint grain and etched. This technique allowed for more fluid, painterly marks compared to traditional line etching, perfectly suiting Robbe's style.

These technical innovations were not merely for show; they were integral to his artistic vision. The softness achieved through aquatint and à la poupée printing perfectly complemented his preferred subjects: intimate moments, quiet interiors, the delicate features of women, and the hazy atmosphere of Parisian parks or seaside resorts. His technical prowess allowed him to infuse his prints with a palpable sense of mood and light. His mentor, Eugène Delâtre, was instrumental in facilitating these experiments, providing the technical support and collaborative environment needed for such advancements.

Themes and Subjects: The Parisian Woman and Modern Life

Thematically, Manuel Robbe's work is deeply rooted in the Belle Époque (roughly 1871-1914), a period characterized by relative peace, prosperity, technological progress, and a flourishing arts scene in Paris. His prints offer intimate glimpses into the lives of the Parisian bourgeoisie, particularly women, who became his most enduring subject.

Robbe depicted the "Parisienne" – the modern, often fashionable, urban woman – in various settings: relaxing in elegant interiors, tending to children, visiting parks, attending the theatre, or enjoying leisure time at the seaside. His portrayal was generally gentle and sympathetic, focusing on moments of quiet reflection, domesticity, or poised elegance. Works like Parisienne (a title he used for several prints) capture the fashionable silhouette and subtle allure of contemporary women. He often depicted them engrossed in everyday activities – reading, sewing, adjusting a hat, or simply gazing thoughtfully.

His approach shows the influence of Impressionist masters like Edgar Degas and Auguste Renoir. From Degas, one can see a shared interest in capturing unposed, intimate moments and innovative compositions, often cropping figures unexpectedly. From Renoir, Robbe seems to have absorbed a love for soft light, delicate color harmonies, and a certain sensuousness in rendering figures and fabrics. The influence of Mary Cassatt, another master printmaker associated with Delâtre and known for her sensitive portrayals of women and children, is also palpable.

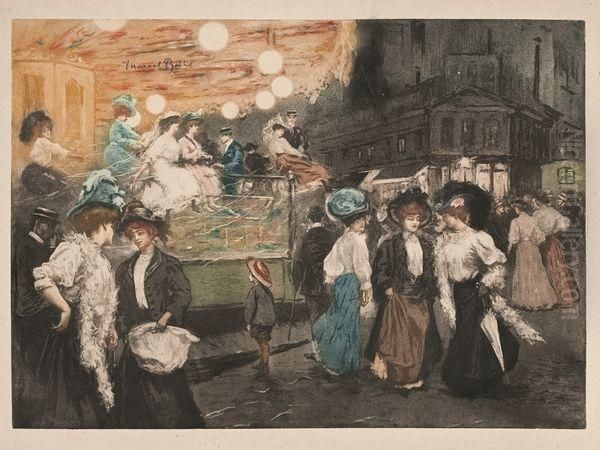

Beyond the figure, Robbe also created evocative cityscapes and landscapes. Prints like Le manège ou la Place Blanche à Paris depict the bustling energy of Parisian public spaces, capturing the movement of crowds and carriages under specific light conditions. His coastal scenes, such as La Plage (The Beach), often feature elegantly dressed women and children enjoying seaside leisure, rendered with the same soft focus and atmospheric sensitivity as his interior scenes. These works reflect the era's growing middle-class engagement with leisure and tourism. Unlike the sometimes critical or satirical edge found in the work of contemporaries like Toulouse-Lautrec or even his teacher Louis Legrand, Robbe's vision was typically more serene and idealized, celebrating the grace and quiet beauty he observed in the world around him.

Recognition and Exhibitions

Manuel Robbe achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime, particularly in the years leading up to World War I. He regularly exhibited his prints at the prestigious annual Salons in Paris, primarily with the Société des Artistes Français. Participation in these Salons was crucial for an artist's reputation and commercial success, exposing their work to critics, collectors, and the public.

A significant milestone was his participation in the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) held in Paris in 1900. This massive international event showcased achievements in industry, technology, and the arts. Robbe's printmaking skills were acknowledged with an award – sources vary, sometimes citing a Bronze Medal, occasionally Silver or Gold, but recognition at this major event undoubtedly boosted his standing. This fair was a pinnacle moment for the Belle Époque and Art Nouveau styles, and Robbe's work fit well within its aesthetic parameters.

His prints were sought after by collectors in France and abroad, facilitated by dealers like Sagot, Pierrefort, and Petit. These dealers often commissioned specific editions, ensuring a steady output and market presence for Robbe. His work was appreciated for its technical virtuosity combined with accessible and charming subject matter. He successfully navigated the art market of his time, producing editions that appealed to the tastes of the burgeoning middle-class collectors who favored intimate, decorative works for their homes.

While perhaps not reaching the widespread fame of some Impressionist painters or the notoriety of avant-garde figures, Robbe was a respected and successful artist within the vibrant printmaking community of his era. His consistent presence at Salons and the support of influential dealers solidified his position as a leading exponent of color aquatint.

Comparisons and Context: Robbe and His Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Manuel Robbe's contribution, it's helpful to place him within the context of his contemporaries. The Parisian art scene at the turn of the century was incredibly diverse. In printmaking alone, various techniques and styles coexisted.

Robbe's focus on color aquatint and intimate subjects aligns him broadly with artists like Mary Cassatt, who also worked closely with Eugène Delâtre and explored themes of women and children with great sensitivity, though Cassatt often employed drypoint alongside aquatint for stronger lines. Jacques Villon, another master etcher (and brother of Marcel Duchamp), explored more modern, Cubist-influenced structures in his prints later on, but his earlier work also shows a dedication to graphic experimentation.

Compared to the bold, graphic style of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec's lithographic posters capturing the gritty energy of Montmartre nightlife, Robbe's work appears more refined, gentle, and focused on bourgeois life. While Lautrec used lithography for its immediacy and suitability for large editions, Robbe's painstaking aquatint process yielded more subtle, atmospheric results in smaller editions. Similarly, the vibrant lithographs of Jules Chéret, often considered the father of the modern poster, have a dynamism and commercial purpose distinct from Robbe's more painterly intaglio prints.

Robbe's depictions of elegant women invite comparison with artists like Paul César Helleu, known for his glamorous drypoint portraits of society ladies, though Helleu's style was often more linear and overtly fashionable. James Tissot, from an earlier generation, also depicted elegant women in contemporary settings, but often with a greater emphasis on narrative and social detail.

Within the broader context of French art, Robbe worked concurrently with the Nabis, such as Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard. While the Nabis also favored intimate domestic scenes and decorative compositions, their use of color was often bolder and more subjective, influenced by Gauguin, and they frequently worked in lithography or painting rather than Robbe's preferred aquatint. Félix Vallotton, another contemporary, used woodcut to create stark, high-contrast images of modern life, offering a stylistic counterpoint to Robbe's soft tones. Even the influence of James McNeill Whistler, whose earlier etching revival work emphasized atmospheric tone, can be seen as part of the background against which Robbe developed his own tonal approach.

Robbe carved his own path, blending Impressionistic sensitivity to light and atmosphere with a mastery of traditional intaglio techniques pushed to new expressive limits through color and innovative processes like sugar-lift and à la poupée.

Later Career and Legacy

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 marked a significant disruption for European society and the art world. The optimistic spirit of the Belle Époque faded, and artistic styles began to shift more dramatically towards Modernism. While details about Robbe's activities during the war are scarce, it seems his prolific period of artistic printmaking slowed down.

After the war, the art world landscape changed considerably. The avant-garde movements that had begun before the war, such as Cubism and Fauvism, gained prominence, and new movements like Surrealism emerged. The taste for Belle Époque elegance and intimate genre scenes, while never disappearing entirely, was less central to the critical discourse. Some sources suggest Robbe may have turned more towards commercial illustration or printing work in his later years, although he continued to create art.

Manuel Robbe passed away in 1936. For several decades following his death, his work, like that of many artists associated with the Belle Époque's more traditional or representational side, received relatively little critical attention. The dominant narrative of 20th-century art history focused heavily on the progression of Modernist abstraction, often marginalizing artists who worked in seemingly less radical styles. The intricate craft of color aquatint also became less common as artistic trends shifted.

Rediscovery and Enduring Appeal

It wasn't until the late 1960s and 1970s that a significant reassessment of late 19th and early 20th-century art began. Scholars and collectors started looking beyond the established canon of Modernism, rediscovering the richness and diversity of artists from the Belle Époque and Art Nouveau periods. Manuel Robbe was among those whose work experienced a revival of interest.

Museums and galleries began organizing exhibitions featuring color prints from the era, and Robbe's name resurfaced. His technical brilliance, particularly in the difficult medium of color aquatint printed à la poupée, was newly appreciated. Collectors were once again drawn to the charm, intimacy, and atmospheric beauty of his prints. Catalogues raisonnés were compiled, helping to solidify his oeuvre and contribution.

Today, Manuel Robbe is recognized as one of the foremost practitioners of color aquatint in France at the turn of the century. His artistic legacy lies in his technical innovations, which allowed him to achieve unique painterly effects in printmaking, and in his sensitive, evocative portrayal of Parisian life and the women of the Belle Époque. His works offer a window into a specific time and place, capturing its aesthetics and atmosphere with remarkable skill and subtlety. While he may not have been a radical avant-gardist, his dedication to his craft and his ability to infuse his prints with quiet emotion and visual beauty secure his place as a significant artist of his time. His prints continue to be sought after by collectors and are held in museum collections around the world, admired for their technical mastery and enduring charm.