Henri Victor Lesur (1863-1900) stands as a fascinating, if somewhat understated, figure in the vibrant tapestry of late 19th-century French art. Active during a period of immense social, technological, and artistic upheaval, Lesur carved a niche for himself by creating charming, meticulously rendered scenes of aristocratic leisure and idealized historical elegance. While his contemporaries, the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, were radically redefining the very nature of painting, Lesur remained committed to a more traditional, albeit highly polished, aesthetic that found favor with a particular segment of the art-buying public. His relatively short life and career, however, mean that his oeuvre, though distinctive, is not as extensive as some of his longer-lived peers.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Roubaix, a town in northern France, on April 28, 1863, Henri Victor Lesur's early life remains somewhat shrouded in obscurity. Detailed records of his childhood or initial artistic inclinations before his formal training are scarce. This is not uncommon for artists of the period who did not achieve immediate, sensational fame or come from already prominent families. What is clear, however, is that his artistic talents were significant enough to gain him entry into the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the traditional gateway for aspiring artists seeking official recognition and a successful career within the established Salon system.

At the École des Beaux-Arts, Lesur came under the tutelage of François Flameng (1856-1923). Flameng was himself a product of the academic tradition, having studied under such luminaries as Alexandre Cabanel and Jean-Léon Gérôme. He was a highly successful painter known for his historical scenes, portraits, and later, his work as an official war artist during World War I. Flameng's own style often harked back to the elegance and refinement of 18th-century art, and this preference undoubtedly left a significant mark on his pupil. Lesur absorbed Flameng's emphasis on precise draughtsmanship, smooth finish, and the depiction of graceful, often anachronistic, subject matter. This master-student relationship was pivotal in shaping Lesur's artistic trajectory, steering him towards genre scenes that celebrated a romanticized vision of the past.

The Parisian Art World: A Time of Transition

To fully appreciate Lesur's artistic choices, it's essential to understand the dynamic and often contentious art world of Paris in the late 19th century. The official art scene was still largely dominated by the Académie des Beaux-Arts and its annual Salon, which acted as the primary venue for artists to exhibit their work and gain patronage. Artists like William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Alexandre Cabanel, and Jean-Léon Gérôme were the titans of this academic tradition, producing large-scale historical, mythological, and allegorical paintings characterized by meticulous detail and a highly polished finish. Their work was celebrated by the establishment and sought after by wealthy collectors.

However, this established order was being challenged by a wave of revolutionary artistic movements. The Impressionists, including Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro, had already made their mark by the time Lesur was a student. They rejected the historical and mythological subjects of the Academy, focusing instead on contemporary life, the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, and a more subjective visual experience, often painting en plein air. Their broken brushwork and vibrant palettes were initially met with derision by critics and the public but gradually gained acceptance.

Following the Impressionists came the Post-Impressionists, such as Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat, and Paul Cézanne, each pushing the boundaries of art in highly individual directions, exploring emotional expression, symbolic color, scientific theories of optics, and the underlying structure of form. Concurrently, Naturalism, an offshoot of Realism championed by figures like Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet in the preceding decades, continued to have proponents like Jules Bastien-Lepage, who depicted rural life and ordinary people with a degree of objective truth, though often with a sentimental gloss.

It was within this complex artistic ecosystem that Henri Victor Lesur developed his style. He consciously eschewed the radicalism of the avant-garde and the gritty realism of the Naturalists. Instead, he aligned himself more closely with the refined aesthetics favored by his teacher, François Flameng, and artists who specialized in historical genre scenes or elegant depictions of contemporary high society, sometimes referred to as "painters of modern life" in a more genteel sense than that applied to Manet or Degas. Artists like Jean Béraud and James Tissot, for instance, captured the fashionable Parisian society of the Belle Époque, though often with a greater sense of contemporary immediacy than Lesur's more overtly nostalgic works.

Lesur's Distinctive Style: Nostalgia and Elegance

Henri Victor Lesur's artistic signature lies in his delicate and charming depictions of figures, often women, in elegant, 18th-century-inspired attire, engaged in leisurely pursuits. His paintings are typically small in scale, often executed on wood panels, which lends them an intimate, jewel-like quality. This choice of support also enhanced their suitability for display in private homes, appealing to bourgeois collectors who desired art that was both decorative and evocative of a more graceful era.

His style is characterized by meticulous attention to detail, particularly in the rendering of fabrics, costumes, and accessories. The silks, satins, and laces of the elaborate gowns are rendered with a palpable sense of texture. Faces are often idealized, conveying a sense of serene beauty and refinement rather than specific portraiture of individuals. While he did undertake portrait commissions, his genre scenes are more about evoking a mood and an atmosphere of bygone elegance than capturing individual likenesses.

A key element of Lesur's appeal was the inherent nostalgia in his work. The late 19th century, despite its technological advancements and societal changes, was also a period where many looked back with fondness to earlier, seemingly simpler or more glamorous times. The Rococo charm of the 18th century, with its associations with artists like Jean-Antoine Watteau, François Boucher, and Jean-Honoré Fragonard, held a particular allure. Lesur tapped into this sentiment, creating images that offered an escape from the complexities and often harsh realities of an increasingly industrialized and rapidly modernizing world. His paintings are not social commentaries; they are fantasies, offering viewers a glimpse into an idealized world of grace, beauty, and leisure.

His color palette tends towards soft, harmonious tones, often with a decorative sensibility that aligns with the Belle Époque's taste for ornamental beauty. This contrasts sharply with the bolder, more experimental color use of the Impressionists or the earthy tones of the Realists. Lesur's brushwork is smooth and controlled, leaving little trace of the artist's hand, a hallmark of academic training that aimed for a polished, "licked" surface.

Key Themes and Subjects

The primary focus of Lesur's oeuvre was the depiction of elegant figures, predominantly women, in settings that suggested wealth and leisure. These were not scenes drawn from his travels or direct observations of contemporary high society in the manner of, say, Giovanni Boldini, whose dynamic portraits captured the vivacity of Belle Époque socialites. Instead, Lesur's figures often seem to inhabit a timeless, idealized past, even when the settings might have contemporary Parisian elements.

His subjects are frequently engaged in genteel activities: strolling in parks, tending to flowers, reading letters, playing musical instruments, or engaging in quiet conversation. These scenes are imbued with a sense of tranquility and refined pleasure. The narrative is usually subtle, focusing more on the aesthetic arrangement of figures and the depiction of beautiful costumes and settings than on dramatic action or complex storytelling.

While he is known for these charming genre scenes, Lesur also produced portraits. These, too, likely reflected the prevailing taste for elegance and idealization, presenting sitters in a flattering and sophisticated light. His training under Flameng, who was a successful portraitist, would have equipped him well for this aspect of his career.

"The Flower Merchant" and Other Notable Works

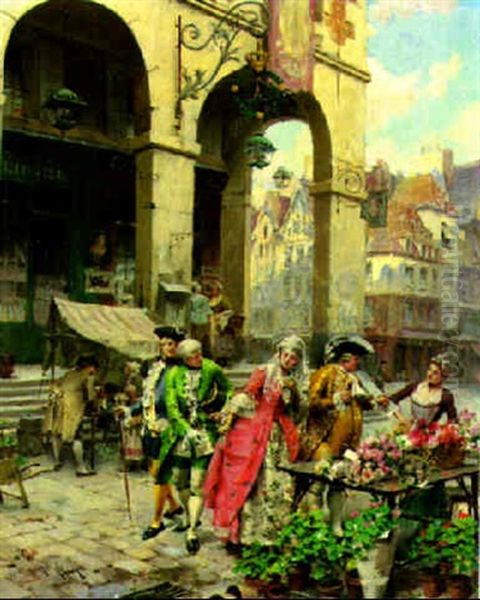

Among Henri Victor Lesur's most representative and well-regarded works is "The Flower Merchant" (Le Marché des Fleurs). This oil painting, typically modest in size (one version is noted as 16 x 12 inches), encapsulates many of the defining characteristics of his art. It depicts a scene, likely in a Parisian setting, where elegantly dressed ladies are interacting with a flower seller. The composition would feature the vibrant colors of the flowers contrasting with the refined attire of the figures, all rendered with Lesur's characteristic attention to detail and smooth finish.

Such a scene allowed Lesur to combine several appealing elements: the beauty of women, the elegance of fashion, and the natural charm of flowers. Flower markets themselves were popular subjects for artists of various schools in the 19th century, from Impressionists like Childe Hassam (an American who painted Parisian scenes) who captured their bustling atmosphere and light, to more academic painters who focused on the picturesque qualities. Lesur's interpretation would lean towards the latter, emphasizing the grace and social interaction within an idealized urban environment. The painting evokes a sense of past Parisian luxury and leisurely daily life, a romanticized snapshot of a bygone era.

Lesur's debut at the prestigious Paris Salon in 1887 was with a work titled "Saint Louis enfant Distribuant des Aumônes" (The Young Saint Louis Distributing Alms). This painting earned him an honorable mention, a significant achievement for a young artist. The choice of a historical religious subject for his Salon debut was a traditional one, demonstrating his academic training and ambition. This work likely showcased his ability to handle more complex compositions and historical narratives, skills honed under Flameng.

Throughout his career, Lesur continued to exhibit at the Salon and also participated in the Expositions Universelles (World's Fairs) held in Paris. He received bronze medals at the Expositions Universelles of 1889 and 1900, further testament to the official recognition his work garnered. These accolades indicate that his art, while not revolutionary, was well-received within the established art institutions of his time and appealed to the prevailing tastes of Salon juries and the public who favored polished, pleasing imagery.

Artistic Context and Contemporaries

While Lesur's style was distinct, he was not working in a vacuum. Other artists catered to similar tastes for elegant, historical, or charmingly anachronistic scenes. Figures like Madeleine Lemaire, known for her flower paintings and society portraits, or artists specializing in "style troubadour" (a romanticized depiction of the Middle Ages and Renaissance popular earlier in the 19th century, but whose echoes persisted) shared some common ground in their appeal to nostalgia and decorative beauty.

His work can be seen as part of a broader current in late 19th-century art that offered an alternative to both the academic grand manner and the avant-garde. This current emphasized craftsmanship, charm, and subjects that were pleasing and aspirational. Artists like the Belgian Alfred Stevens, active in Paris, also painted elegant women in luxurious interiors, though often with a more contemporary feel and psychological depth than Lesur. The enduring popularity of 18th-century revival styles in decorative arts and fashion during the Belle Époque provided a receptive cultural backdrop for Lesur's paintings.

His decision to paint on small wood panels also aligns him with a tradition of "cabinet pictures," intimate works intended for close viewing in domestic settings, a practice that had been popular since the Dutch Golden Age with artists like Gerard ter Borch or Gabriël Metsu, and saw revivals in various periods. This contrasts with the large canvases intended for public Salon display, though Lesur, as noted, also produced works for the Salon.

Legacy and Conclusion

Henri Victor Lesur's career was tragically cut short by his early death in 1900, at the age of just 37. This limited the full development of his artistic vision and the extent of his oeuvre. Consequently, he does not occupy the same prominent position in art history as many of his contemporaries who lived longer and produced a more substantial body of work, or those who broke more radically with tradition, such as the aforementioned Impressionists or Post-Impressionists like Paul Signac or Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who were also capturing different facets of Parisian life.

Nevertheless, Lesur's paintings remain a charming testament to a particular aesthetic sensibility of the Belle Époque. His work offers a window into a world of idealized elegance and romantic nostalgia that held considerable appeal for audiences seeking refuge from the rapid changes of modernity. He was a skilled craftsman who excelled in creating delicate, beautifully finished images that celebrated grace and beauty.

Today, his paintings are appreciated by collectors who value their decorative qualities, their technical finesse, and their evocative portrayal of a bygone era. While he may not have been an innovator in the mold of a Monet or a Cézanne, Henri Victor Lesur successfully carved out a niche for himself, producing art that brought pleasure to his contemporaries and continues to charm viewers more than a century later. His work serves as a reminder that the art world of any period is diverse, encompassing a wide range of styles and artistic intentions, from the revolutionary to the reassuringly traditional. Lesur firmly belonged to the latter, offering a gentle, polished vision of beauty in an age of artistic ferment.