Félix-Hilaire Buhot stands as one of the most innovative and evocative printmakers of the late nineteenth century in France. Active during a period of immense artistic ferment, Buhot carved a unique niche for himself, distinct from yet connected to the Impressionist movement. He was a master technician, an obsessive experimenter, and an artist acutely sensitive to the nuances of atmosphere and the poetry of modern life. His etchings and drypoints, often enhanced with aquatint, roulette, and sometimes even watercolour, capture the fleeting moments of Parisian street life, the dramatic weather of the Normandy coast, and the bustling energy of London harbours with unparalleled skill and emotional depth. Known affectionately and accurately as a "painter-etcher" ("peintre-graveur"), Buhot elevated printmaking to a primary form of artistic expression, leaving behind a body of work celebrated for its technical brilliance and haunting beauty.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

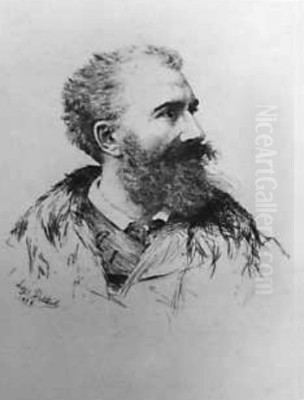

Félix-Hilaire Buhot was born on July 9, 1847, in the town of Valognes, located in the picturesque Normandy region of France. His early life was marked by hardship; orphaned at a young age, he was raised by his godfather. This challenging start perhaps instilled in him a certain resilience but also a sensitivity that would later permeate his art. Seeking broader horizons and formal artistic training, the young Buhot made the pivotal move to Paris in 1865, at the age of eighteen.

In the vibrant artistic capital, Buhot enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the traditional heart of academic art training in France. There, he studied the fundamentals of painting and drawing. However, his path took a decisive turn towards printmaking when he began studying etching techniques under the guidance of Isidore Pils, a painter known for his historical and military scenes but also involved in graphic arts. This mentorship provided Buhot with the foundational skills in a medium that would become his primary passion and the vehicle for his most significant artistic contributions. The rigorous training, combined with the stimulating environment of Paris, set the stage for his emergence as a unique voice in French art.

The Rise of a Painter-Etcher

Buhot created his first etching in 1873, and his talent quickly became apparent. He rapidly gained recognition as a successful printmaker, embracing the medium not merely as a means of reproduction but as a primary creative outlet. This aligned him with the burgeoning "Etching Revival" movement, which championed the expressive potential of original prints. Buhot fully embodied the ideal of the "peintre-graveur" (painter-etcher), an artist who uses the etching needle and the copper plate with the same freedom and personal expression as a painter uses brushes and canvas.

His success was not confined to France. Buhot frequently exhibited his works in London, finding a receptive audience there. By 1879, he had achieved considerable success across the Channel, demonstrating the international appeal of his unique vision. His prints began to enter important collections, both private and public, securing his reputation during his lifetime. He became known for his meticulous craftsmanship, his innovative spirit, and his ability to translate the ephemeral qualities of light and atmosphere onto the copper plate, creating works often described as "paintings on copper."

Technical Mastery and Innovation

What truly set Félix Buhot apart was his extraordinary technical command and relentless experimentation with printmaking processes. He was not content to master a single technique but instead combined multiple methods on a single plate to achieve unprecedented richness and complexity. Etching formed the backbone of his work, providing the linear structure, but he masterfully layered it with drypoint for velvety blacks and expressive lines, aquatint for tonal washes that captured fog or rain-slicked streets, and the textured effects of roulette and other tools. He sometimes further enhanced impressions with watercolour or gouache, blurring the lines between printmaking and painting.

Buhot constantly experimented with the printing process itself. He explored different types of paper, sometimes printing on heavily soaked sheets to achieve softer, more atmospheric effects. He varied the way he wiped the ink from the plate, understanding that this could dramatically alter the mood and tonality of the final impression. He experimented with coloured inks and different paper tones, always seeking the perfect combination to convey his intended atmosphere. This dedication to the craft, this constant pushing of boundaries, resulted in prints of remarkable subtlety and depth.

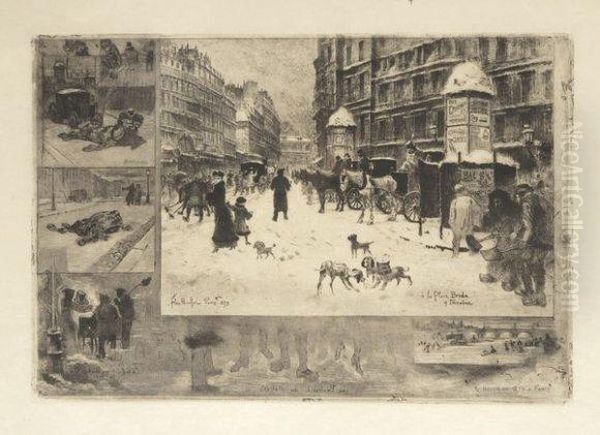

The Symphonic Margins

Perhaps Buhot's most distinctive and celebrated innovation was his development of what he termed "marges symphoniques," or symphonic margins. Rejecting the traditional notion of a clear boundary between the central image and the edge of the plate, Buhot often surrounded his main subject with a series of smaller vignettes, sketches, and remarques directly related to the central theme. These marginalia were not mere decorations; they functioned as commentaries, expansions, or atmospheric echoes of the main scene.

In a print depicting a rainy Parisian boulevard, the margins might contain sketches of huddled figures, dripping umbrellas, or reflections in puddles. For a harbour scene, the margins could feature details of rigging, seabirds, or distant ships. This technique created a dynamic interplay between the centre and the periphery, enriching the narrative and visual experience. The term "symphonic" aptly suggests a musical analogy, with the margins providing contrapuntal themes or harmonic resonances that deepen the impact of the main composition. These margins transformed the print into a more complex, layered object, inviting prolonged contemplation and revealing Buhot's keen observational skills and imaginative mind.

Capturing Atmosphere and Modern Life

Buhot possessed an exceptional ability to capture atmospheric conditions and the specific moods they evoked. He became a renowned interpreter of weather, particularly the effects of rain, snow, fog, mist, and the ethereal glow of gaslight in the urban night. His cityscapes, whether of Paris or London, are often imbued with a palpable sense of humidity, chill, or nocturnal mystery. He rendered the slick sheen of wet pavements, the soft diffusion of light through fog, and the delicate patterns of falling snow with remarkable sensitivity.

His subject matter was drawn primarily from the world around him. The streets, boulevards, and public spaces of Paris, especially areas near his Montparnasse home like the Boulevard de Clichy, were frequent sources of inspiration. He depicted the bustling crowds, the horse-drawn carriages, the fashionable pedestrians, but also the working-class figures and their animals, showcasing the diverse social fabric of the modern city. He was equally adept at capturing the maritime life of Normandy's ports, like Saint-Malo, and the distinctive atmosphere of London, particularly its docks and river scenes. His work reflects a deep engagement with the visual experiences of late nineteenth-century urban and coastal life.

Influence of Japonisme

Like many artists of his generation, Félix Buhot was significantly influenced by Japanese art, a phenomenon known as Japonisme that swept through Europe in the latter half of the nineteenth century. He was among the earlier French artists to absorb and adapt elements of Japanese aesthetics into his work. This influence is evident in his compositions, which sometimes feature flattened perspectives, asymmetrical arrangements, and decorative patterning reminiscent of Ukiyo-e woodblock prints.

His series Japonisme (Dix Eaux-fortes), created between 1875 and 1881, explicitly engages with this influence, incorporating Japanese motifs and stylistic devices. Beyond specific references, the Japanese sensibility likely reinforced Buhot's own interest in atmospheric effects, suggestive compositions, and the integration of decorative elements, as seen in his symphonic margins. This engagement with non-Western art added another layer of sophistication and visual interest to his already innovative style, placing him alongside contemporaries like James McNeill Whistler and Félix Bracquemond who were also exploring these cross-cultural currents.

Key Works and Themes

Buhot's oeuvre includes numerous masterpieces that exemplify his style and thematic concerns. L'Hiver à Paris (Winter in Paris, 1879) is a quintessential example of his ability to capture the cold, damp atmosphere of the city in winter, complete with intricate details of street life and often featuring his signature symphonic margins depicting related scenes. Another iconic work is Une Matinée d'Hiver au Quai de l'Hôtel Dieu (A Winter Morning on the Quai de l'Hôtel Dieu, often related to Débarquement en Angleterre or A Landing in England, 1879), which masterfully uses drypoint and roulette to convey the bustling, misty atmosphere of a Parisian quay or potentially a London dockside scene.

La Fête Nationale au Boulevard Clichy (National Celebration on the Boulevard Clichy, c. 1878) showcases his skill in depicting nocturnal scenes illuminated by festive lights, capturing the energy and specific light quality of a public celebration. His love for the sea and dramatic coastal scenery is evident in La Falaise - Baie de Saint-Malo (The Cliff - Saint-Malo Bay, 1886/1887) and Les Grandes Vagues (The Great Waves, c. 1880s), where he explores the power and moodiness of the ocean. La Messe de Minuit (The Midnight Mass, 1887), an intricate etching combining various techniques, demonstrates his ability to handle complex figural compositions and interior light. Early works like the frontispiece for L'Illustration Nouvelle (1877) and pieces from his Japonisme series highlight his early development and engagement with contemporary artistic trends.

Artistic Circle and Contemporaries

Félix Buhot did not work in isolation. He was an active participant in the Parisian art world and associated with several leading figures of his time. His most significant connections were perhaps with the Impressionists, particularly Edgar Degas and Camille Pissarro. While Buhot's style remained distinct, he shared their interest in capturing fleeting moments, atmospheric effects, and scenes of modern life. His technical experimentation in printmaking paralleled the explorations Degas was undertaking in monotype and etching.

In 1889, Buhot, along with Degas, Pissarro, Félix Bracquemond, Henri Guérard, and others, became a founding member of the Société des Peintres-Graveurs Français (Society of French Painter-Etchers). This society aimed to promote original printmaking as a fine art form, distinguishing it from reproductive engraving. His involvement underscores his commitment to the medium and his standing among its foremost practitioners.

His contemporaries and the broader artistic context included influential figures like Édouard Manet, whose earlier prints had already explored modern Parisian life; Mary Cassatt, another Impressionist deeply involved in innovative printmaking, especially colour etching influenced by Japanese prints; and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who would revolutionize lithography slightly later. Buhot's work can also be seen in relation to James McNeill Whistler, whose atmospheric etchings of London and Venice share certain sensibilities, and James Tissot, who also depicted modern life in Paris and London. Earlier figures like Charles Meryon, with his haunting etchings of Paris, provided a precedent for urban printmaking, while unique talents like Rodolphe Bresdin explored fantastical realms through etching. Alphonse Legros, another important French etcher who spent much of his career in London, was also part of this rich printmaking landscape. Even Paul Gauguin, primarily a painter, experimented with printmaking, reflecting the medium's appeal during this era. Buhot navigated this complex scene, absorbing influences while forging his own unmistakable path.

Challenges and Later Years

Despite his artistic success and recognition, Buhot's personal life was fraught with difficulties. He suffered from periods of mental instability and depression, which significantly impacted his well-being and productivity. Sources indicate that he was institutionalized on at least two occasions due to his mental health struggles. Furthermore, he experienced brief periods of imprisonment in 1885 and 1886, although the specific reasons are often unclear in historical accounts.

His artistic process itself seems to have been a source of both fulfillment and torment. He was known for his obsessive perfectionism, constantly reworking his plates through numerous states, or "proofs." He once lamented how these proofs "completely devoured" his time, energy, and mind. This relentless drive for the perfect expression, while resulting in technically brilliant and nuanced works, likely contributed to his personal strain. Tragically, his struggles culminated in his premature death. Félix Buhot passed away in Paris on April 26, 1898, at the age of 51, reportedly due to long-term depression. His death cut short the career of one of France's most original graphic artists.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Félix-Hilaire Buhot left an indelible mark on the history of printmaking. He is widely regarded as one of the most important and innovative French etchers of the late nineteenth century, a key figure in the Etching Revival who championed the expressive possibilities of the medium. His technical virtuosity, particularly his skillful combination of multiple intaglio techniques and his invention of the "marges symphoniques," set his work apart and influenced subsequent generations of printmakers.

His ability to capture subtle atmospheric effects – the dampness of rain, the swirl of fog, the glow of twilight – remains unparalleled. He brought a poet's sensitivity to his depictions of modern urban life and coastal landscapes, infusing them with mood and emotion. His work resonated particularly strongly in the United States, where collectors and museums recognized his talent early on; the first solo exhibition of his work was held in New York in 1888, contributing significantly to his international reputation.

Today, Buhot's prints are held in major museum collections worldwide, including the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris, the British Museum in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Art Institute of Chicago. His work continues to be admired for its technical brilliance, its evocative power, and its unique window onto the world of Belle Époque France. As a "painter-etcher" who dedicated his life to exploring the full potential of the copper plate, Félix Buhot secured his place as a true master of graphic art.