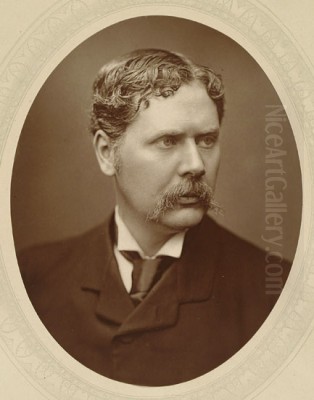

Marcus Stone RA (1840-1921) stands as a significant figure in the landscape of Victorian art, a painter and illustrator whose work captured the nuances of emotion, narrative, and social interaction that defined his era. Born into an artistic milieu, he navigated the London art world with considerable success, achieving recognition from the Royal Academy and popularity with the public. His canvases, often depicting scenes of courtship, quiet contemplation, and historical vignettes, are characterized by their meticulous detail, gentle sentiment, and accessible storytelling. Stone bridged the worlds of fine art and literature, most notably through his collaborations with Charles Dickens, leaving behind a legacy rich in visual charm and narrative depth.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Marcus Clayton Stone was born in London on July 4, 1840. His artistic inclinations were nurtured from a young age, heavily influenced by his father, Frank Stone ARA (1800-1859). Frank Stone was himself a respected painter, known for his genre scenes and portraits, and a member of the esteemed Royal Academy of Arts. He was also a close friend of the literary giant Charles Dickens, a connection that would prove pivotal in Marcus's own career. Frank provided his son with his initial artistic training, immersing him in the techniques and sensibilities prevalent in the mid-19th century British art scene.

This paternal guidance provided a strong foundation, and Marcus demonstrated precocious talent. He began exhibiting his work publicly at a remarkably young age. By the time he was just seventeen or eighteen, his paintings were accepted for display at the prestigious annual exhibitions of the Royal Academy, a significant achievement for an artist yet to reach full maturity. This early success signalled the arrival of a promising new talent on the London art stage.

While largely taught by his father, Marcus Stone's development also occurred within the broader context of the Royal Academy Schools, although records of his formal enrolment are debated. He certainly moved within its orbit, absorbing the academic traditions and interacting with the leading figures and prevailing styles of the time. His formative years coincided with the flourishing of various artistic trends, from the detailed realism advocated by the Pre-Raphaelites to the established narrative and historical painting traditions upheld by the Academy. He would have been aware of, and likely studied alongside or under the influence of, figures associated with the Academy, such as the popular narrative painter William Powell Frith and the meticulous genre artist William Mulready. The powerful, morally charged realism of William Holman Hunt, a key Pre-Raphaelite figure, also formed part of the artistic environment Stone navigated.

The Influence of Dickens and Literary Illustration

One of the most defining aspects of Marcus Stone's early career was his close association with Charles Dickens. Inheriting the friendship from his father, Marcus developed his own rapport with the celebrated novelist. This connection provided him with unparalleled opportunities in the burgeoning field of literary illustration. Dickens, recognizing the young artist's talent and perhaps his ability to capture character and atmosphere, commissioned him for significant projects.

Stone's illustrations for the later works of Dickens cemented his reputation. He provided the illustrations for Our Mutual Friend (published in parts 1864-1865), taking over from Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"), who had illustrated most of Dickens's earlier novels. Stone adopted a more realistic, less caricatured style than Phiz, aligning with the changing tastes of the time and the darker, more complex tone of Dickens's later writing. His depictions of characters like Lizzie Hexam, Eugene Wrayburn, and the Veneerings were praised for their naturalism and psychological insight.

Following Our Mutual Friend, Stone also created illustrations for the Library Edition of Great Expectations (1862) and later contributed illustrations for other posthumous editions of Dickens's works, including David Copperfield. His work for Dickens required keen observation and an ability to translate the author's vivid prose into compelling visual form. Stone's illustrations often focused on key moments of character interaction and emotional revelation, rendered with clarity and sensitivity.

A fascinating anecdote highlights Stone's contribution beyond mere illustration. It is said that Stone discovered a peculiar shop belonging to a taxidermist named Mr. Venus, filled with articulated skeletons and preserved specimens. He introduced Dickens to this curious establishment, which directly inspired the character of Mr. Venus and his shop in Our Mutual Friend. This incident underscores the collaborative potential between author and illustrator and Stone's eye for the unique details that could enrich a narrative.

Beyond Dickens, Stone also provided illustrations for other prominent authors of the Victorian era. He notably illustrated Anthony Trollope's novel He Knew He Was Right (1869), demonstrating his versatility in adapting his style to different literary voices. His work appeared in popular periodicals like the Cornhill Magazine, placing his art before a wide readership. In this field, he worked alongside other notable illustrators of the day, such as Luke Fildes, who also famously illustrated Dickens, and George du Maurier, known for his society illustrations in Punch. Stone's success in illustration provided financial stability and public recognition, complementing his burgeoning career as a painter.

Development of Artistic Style

Marcus Stone's artistic journey saw an evolution in both subject matter and style. While his early works, exhibited at the Royal Academy, sometimes touched upon historical themes, such as Edward II and his Favourite, Piers Gaveston, he soon found his true métier in genre painting, particularly scenes depicting contemporary life, courtship, and quiet domestic or garden narratives, often imbued with a sense of nostalgia or gentle sentiment.

His style moved away from the overt moralizing or complex symbolism found in some contemporary movements like Pre-Raphaelitism. Instead, Stone cultivated a refined realism focused on accurate depiction, particularly of costume, setting, and human expression. His figures are rendered with anatomical correctness and individuality, avoiding caricature even in narrative moments. He possessed a keen eye for the textures of fabrics – silks, satins, woollens – and the play of light on surfaces, lending his scenes a tangible quality.

Stone developed a distinctive approach to colour, often employing a palette that was clear, bright, and harmonious, contributing to the generally pleasant and accessible mood of his paintings. He excelled in capturing subtle emotional states – the tentative glance of a lover, the quiet melancholy of solitude, the gentle humour of social interaction. His compositions are typically well-balanced and clearly structured, guiding the viewer's eye through the narrative elements of the scene.

While rooted in realism, Stone's work often carried a strong romantic sensibility. He frequently depicted idealized scenes of courtship set in picturesque gardens or elegant interiors. These paintings resonated with Victorian audiences, offering charming glimpses into moments of private emotion and social ritual. His focus shifted increasingly towards these themes, moving from the potentially broader historical canvases of his youth to the more intimate and sentiment-driven subjects that became his hallmark. This focus on relatable human emotion, presented with technical finesse, secured his popularity.

Signature Themes and Subjects

The recurring themes in Marcus Stone's oeuvre revolve around love, courtship, companionship, and moments of quiet reflection, often set within idyllic garden landscapes or tastefully appointed Regency-era interiors. He became particularly associated with what might be termed "garden party" scenes, though often depicting more intimate encounters within these settings. These works frequently feature young men and women engaged in the subtle dramas of burgeoning romance.

A quintessential example is In Love (1888), exhibited at the Royal Academy. This painting depicts a young couple seated on a garden bench, absorbed in each other's company. The woman gazes intently at her suitor, while he looks away, perhaps contemplating his feelings or the words he wishes to speak. The setting is lush and detailed, the costumes are rendered with Stone's characteristic precision, and the emotional atmosphere is one of tender intimacy and unspoken connection. The painting's popularity led Stone to revisit the theme and even translate it into sculpture.

Another well-known work, Two's Company, Three's None (1892), explores a slightly different dynamic. Here, a couple enjoys a private moment on a garden seat, while a third figure, a young woman, stands apart, observing them with an expression that could suggest longing, exclusion, or perhaps quiet resignation. The painting deftly captures the social complexities and emotional undercurrents that can accompany romance. The title itself, a common idiom, underscores the narrative clarity Stone aimed for.

Stone often employed settings and costumes that evoked the late 18th or early 19th century (Regency period), contributing to a sense of romantic nostalgia. This historical distancing allowed for a focus on timeless themes of love and human relationships, presented with a degree of elegance and charm that appealed to Victorian sensibilities. His paintings rarely tackled gritty social realism in the manner of artists like Hubert von Herkomer or Luke Fildes; instead, they offered a more idealized and aesthetically pleasing vision of human interaction. His work can be compared to that of contemporaries like James Tissot, who also depicted scenes of modern life and courtship, though often with a sharper, more fashionable edge.

His dedication to these themes was consistent throughout his mature career. Paintings like A Prior Attachment, The Peacemaker, and A Passing Cloud further explore the nuances of relationships, misunderstandings, and reconciliations, always rendered with his signature blend of detailed realism and gentle sentiment. These works, widely reproduced as engravings, made Stone's vision of romance and quiet contemplation familiar to households across Britain and beyond.

Academic Recognition and Later Career

Marcus Stone's consistent exhibition record at the Royal Academy and the growing popularity of his work led to formal recognition from the institution. In 1877, he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA), a significant step confirming his status within the British art establishment. Ten years later, in 1887, he achieved the highest rank, being elected a full Royal Academician (RA). This honour placed him among the leading artists of his generation, alongside figures like Frederic Leighton, John Everett Millais, and Lawrence Alma-Tadema, who dominated the Academy's exhibitions.

As a Royal Academician, Stone continued to be a regular and prominent exhibitor at the annual Summer Exhibitions. His paintings were often favourably reviewed and eagerly anticipated by the public. He maintained his focus on the sentimental genre scenes and historical vignettes that had brought him success, refining his technique and exploring variations on his preferred themes. His position within the Academy solidified his reputation and ensured his work remained visible and influential.

Interestingly, Stone also experimented briefly with sculpture, translating some of his popular painted themes into three dimensions. Works like the sculptural version of In Love and another piece titled Il y a toujours un autre (There is always another) demonstrate his interest in exploring romantic narratives across different media. While painting remained his primary focus, these sculptural works offer another facet of his artistic engagement with themes of love and relationships.

In his later years, Stone remained an active figure in the London art world. He resided for many years at No. 8 Melbury Road in Holland Park, an area favoured by many successful Victorian artists, including Leighton, Watts, and Fildes, forming part of a vibrant artistic community. In 1920, reflecting his long service and esteemed position, he was elevated to the status of Senior Academician. He continued to paint until shortly before his death. Marcus Stone passed away in London on March 24, 1921, at the age of 81, leaving behind a substantial body of work that had significantly shaped the visual culture of the Victorian and Edwardian eras.

Context within Victorian Art

Marcus Stone occupied a distinct and popular niche within the diverse landscape of Victorian art. His career spanned a period of significant artistic change, from the lingering influence of Romanticism and the rise of the Pre-Raphaelites in his youth, through the dominance of Academic painting in his middle age, to the emergence of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism towards the end of his life. While not an avant-garde innovator, Stone represented a highly successful strand of mainstream Victorian painting that prioritized narrative clarity, technical accomplishment, and relatable sentiment.

His work stands in contrast to the intense symbolism and medievalism of early Pre-Raphaelites like Dante Gabriel Rossetti or the moral intensity of William Holman Hunt. While sharing a commitment to detailed observation with the Pre-Raphaelites, Stone's aims were different – less concerned with radical reform or spiritual allegory, more focused on capturing the gentle dramas of everyday life and historical romance.

Compared to the grand classical or mythological subjects favoured by Academy presidents like Frederic Leighton, or the meticulously researched historical reconstructions of Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Stone's paintings were more intimate in scale and subject matter. His focus on courtship and garden scenes aligned him more closely with other genre painters, though his style was generally less flamboyant than that of James Tissot and less focused on large-scale contemporary social panoramas than William Powell Frith's famous works like Derby Day.

Stone's emphasis on storytelling connected him to a strong British tradition of narrative art. His illustrations, particularly for Dickens and Trollope, placed him firmly within the important Victorian intersection of literature and visual art, a field also occupied by distinguished contemporaries like John Everett Millais (in his illustration phase) and Luke Fildes. His ability to create accessible and emotionally resonant images made his work highly suitable for reproduction, and engravings after his paintings achieved widespread popularity, much like those after works by Millais or George Frederic Watts.

While Impressionism was developing in France and gradually influencing British artists, Stone remained largely committed to the detailed, realistic style favoured by the Royal Academy and its patrons. He represented the enduring appeal of traditional craftsmanship and narrative painting throughout the late Victorian and Edwardian periods. His consistent success at the Academy exhibitions and the public affection for his work testify to his skill in meeting the tastes of his time.

Legacy and Collections

Marcus Stone's legacy lies primarily in his contribution to Victorian genre painting and illustration. He created a body of work that expertly captured the sentimental inclinations and narrative interests of his era. His paintings, particularly those depicting courtship in garden settings, became iconic representations of Victorian romance, widely disseminated through popular engravings and prints. This ensured his imagery reached a broad audience far beyond the walls of the Royal Academy or private collections.

His illustrations for Charles Dickens remain a significant part of his legacy, offering a distinct visual interpretation of the author's later novels. They mark a transition in Dickensian illustration towards greater realism and psychological nuance, influencing subsequent illustrators. His work for Anthony Trollope and contributions to periodicals further underscore his importance in the visual culture of 19th-century literature.

Today, Marcus Stone's paintings are held in numerous public collections, primarily in the United Kingdom. The Manchester Art Gallery holds several important examples of his work. His paintings can also be found in institutions such as Tate Britain, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and various regional galleries. These collections preserve his contribution to British art history, allowing contemporary audiences to appreciate his technical skill and his particular vision of Victorian life and sentiment.

While artistic tastes shifted dramatically in the 20th century, leading to a period where Victorian narrative painting fell out of critical favour, there has been a renewed appreciation for the skill, charm, and cultural insight offered by artists like Marcus Stone. He is remembered as a highly accomplished painter and illustrator, a master of sentimental narrative, and a key figure in the artistic life of the Royal Academy during the latter half of the 19th century. His work provides a valuable window onto the aesthetics and emotional landscape of the Victorian era.

Conclusion

Marcus Stone RA navigated the Victorian art world with considerable skill and success. From his early debut at the Royal Academy, guided by his artist father Frank Stone, to his established position as a leading Academician, he consistently produced works that resonated with public taste. His collaborations with Charles Dickens cemented his place in the history of illustration, while his paintings of courtship, romance, and quiet contemplation, rendered with meticulous detail and gentle sentiment, became defining images of their time. Though not an artistic revolutionary, Stone was a master craftsman and an adept storyteller in paint, creating a legacy of charming and emotionally accessible works that continue to offer insight into the heart of the Victorian era. His long and productive career, spanning from 1840 to 1921, left an indelible mark on British art.