John Dawson Watson, a prominent figure in the rich tapestry of Victorian art, carved a distinguished career as a painter, watercolourist, and, perhaps most notably, an illustrator. Born in Sedbergh, Yorkshire, on May 20, 1832, and passing away in Conwy, Wales, on January 3, 1892, Watson's life and work offer a fascinating window into the artistic currents and social preoccupations of his era. His contributions spanned various media, earning him recognition in esteemed institutions and leaving behind a legacy of evocative imagery that continues to resonate.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Watson's artistic inclinations emerged early. His father, Miles Watson, was a house painter and an amateur artist himself, likely fostering an environment where creative pursuits were encouraged. The young Watson's formal artistic education began at the Manchester School of Design, a significant provincial institution that played a role in training many artists who would contribute to Britain's industrial and artistic prowess. His ambition and talent soon led him to the heart of the British art world, London, where he enrolled in the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in 1851.

The Royal Academy Schools provided a rigorous academic training, emphasizing drawing from the antique and the live model, and instilling the principles of composition and perspective that were foundational to nineteenth-century art. During his time there, Watson would have been exposed to the prevailing artistic debates, including the rising influence of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, whose emphasis on truth to nature, detailed finish, and morally resonant subjects was challenging academic conventions. While Watson never became a formal member of the PRB, their aesthetic undoubtedly left an impression on his developing style.

The Illustrator's Flourishing Craft

The mid-Victorian era witnessed an explosion in illustrated periodicals and books, fueled by advancements in printing technology, particularly wood engraving, and a burgeoning literate middle class eager for visual accompaniment to their reading. John Dawson Watson emerged as one of the most prolific and skilled illustrators of this "golden age" of British illustration, often associated with the "Idyllic School" or "Sixties School" of illustrators. These artists, including luminaries like Frederick Walker, George John Pinwell, and Arthur Boyd Houghton, brought a new level of artistry and sensitivity to book and magazine illustration.

Watson's work graced the pages of many leading publications of the day, such as Once a Week, Good Words, The Sunday Magazine, The Illustrated London News, and The Graphic. His ability to translate narrative into compelling visual form made him a sought-after collaborator for authors and publishers. He possessed a keen eye for character and a talent for composing scenes that were both informative and emotionally engaging. His drawings for wood engraving were meticulously detailed, understanding the specific requirements of the medium and working closely with skilled engravers like the Dalziel Brothers, who were instrumental in producing high-quality prints.

Among his most celebrated book illustrations are those for editions of John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress (1860), Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe (1864), and Alfred Tennyson's Poems. These projects showcased his versatility, from the spiritual allegories of Bunyan to the adventurous spirit of Defoe and the romantic lyricism of Tennyson. His illustrations for Arabian Nights also demonstrated his capacity for imaginative and exotic subjects. One of his notable single wood engravings, Saved from the Wreck (also known as Saved from the Shipwreck), published as a supplement to Harper's Weekly on December 23, 1871, exemplifies his dramatic power and technical skill in this medium.

Mastery in Watercolour

Beyond his prolific work as an illustrator, John Dawson Watson was an accomplished watercolourist. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Watercolour Society (ARWS) in 1864 and became a full member (RWS) in 1869, a testament to his standing in this demanding medium. The Royal Watercolour Society was a bastion of the British watercolour tradition, and membership was a significant mark of distinction.

His watercolours often depicted subjects similar to those found in his illustrations and genre paintings: intimate domestic scenes, charming portrayals of children, and picturesque rural life. Works like Hanging out the Washing (1884) and The Meeting Place by the Water's Edge (1876) are fine examples of his watercolour technique, characterized by a delicate touch, luminous colour, and an ability to capture atmosphere and sentiment. He skillfully balanced detailed observation with a pleasing compositional harmony, making his watercolours highly popular with the Victorian public. His contributions to the RWS exhibitions were consistent and well-received, further solidifying his reputation.

Oil Paintings and Genre Scenes

John Dawson Watson also worked in oils, producing genre paintings that explored themes of everyday life, historical vignettes, and moments of quiet contemplation. He began exhibiting at the Royal Academy in 1853, with early works like The Artist's Studio. Over the subsequent decades, he would show numerous paintings there, including titles such as Woman's Work, Thinking It Out, Saved, The Stolen Meeting, The Plague of Her Life, The Old Clock, and The Glee Man.

His oil paintings often shared the narrative clarity and emotional accessibility of his illustrations. He had a particular fondness for subjects involving children, capturing their innocence and playfulness with a sympathetic eye. Historical and literary themes also appeared in his oeuvre, sometimes with a romantic or sentimental inflection typical of the period. While perhaps not as groundbreaking as some of his more avant-garde contemporaries, Watson's oil paintings were well-crafted, appealing, and found a ready audience. He also exhibited at other significant venues, including the British Institution and the Society of British Artists on Suffolk Street, and later at the Grosvenor Gallery, which was known for showcasing more aesthetic and less conventional art.

Artistic Style and Influences

Watson's artistic style is firmly rooted in the Victorian narrative tradition. His work is characterized by careful draughtsmanship, a strong sense of composition, and an attention to detail that lends authenticity to his scenes. There is often a palpable sense of sentiment and pathos in his depictions of human relationships and everyday struggles, qualities highly valued by Victorian audiences.

The influence of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, particularly in its earlier, more naturalistic phase, can be discerned in Watson's meticulous rendering of textures, his use of clear, bright colour (especially in his watercolours), and his commitment to conveying the emotional core of his subjects. Artists like John Everett Millais, a founding member of the PRB who also became a highly successful illustrator, shared some common ground with Watson in their approach to narrative and detail. However, Watson's art generally avoided the more intense symbolism or medievalism of core Pre-Raphaelites like Dante Gabriel Rossetti or William Holman Hunt.

His work as an illustrator places him alongside figures like Frederick Walker, George John Pinwell, and Arthur Boyd Houghton, who, like Watson, brought a painterly sensibility to the art of wood engraving. They often depicted scenes of contemporary rural and urban life with a blend of realism and poetic feeling. Watson's ability to capture gesture and expression was crucial to his success in conveying stories through static images. He also shared with artists like Myles Birket Foster a love for idyllic rural scenes and the charm of childhood, though Watson's figures often possessed a greater psychological depth.

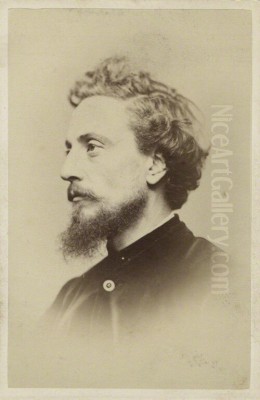

Other contemporaries whose work provides context for Watson's include genre painters like William Powell Frith, known for his sprawling panoramas of Victorian life, and social realist painters such as Luke Fildes and Hubert von Herkomer, who often tackled more challenging social themes. While Watson's subjects were generally less overtly critical, his observations of human behaviour and social customs were nonetheless acute. The photographer David Wilkie Wynfield, known for his artistic portraits of contemporary artists in historical costume, captured Watson in a striking photograph, underscoring his place within this vibrant artistic community.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Several of John Dawson Watson's works stand out for their representative qualities and artistic merit.

The Stolen Meeting: This title, exhibited at the Royal Academy, suggests a clandestine encounter, a popular theme in Victorian genre painting that allowed for the exploration of romantic intrigue and social mores. Such a work would likely showcase Watson's skill in conveying narrative through subtle gestures and expressions, set within a carefully detailed environment that might hint at the social status and circumstances of the figures involved.

Saved from the Wreck (1871): This powerful wood engraving, also known by slight variations in title, is a prime example of Watson's illustrative prowess. It typically depicts a dramatic rescue scene, charged with emotion and action. The composition would be dynamic, focusing on the human drama of survival against the elements. As an illustration for a popular periodical like Harper's Weekly, it needed to grab the viewer's attention immediately and convey the story's essence with clarity and impact. The fine lines and tonal contrasts achievable in wood engraving would have been expertly utilized by Watson to create a sense of texture, movement, and atmosphere.

Hanging out the Washing (1884): This watercolour exemplifies Watson's charm in depicting domestic and rural subjects. The seemingly mundane act of hanging laundry is transformed into a picturesque scene, likely featuring a comely female figure or children in a rustic setting. Watson's skill in watercolour would be evident in the rendering of light, the textures of fabric, and the freshness of the outdoor atmosphere. Such works appealed to the Victorian appreciation for domestic virtue and the perceived innocence of country life.

Illustrations for The Pilgrim's Progress: Watson's illustrations for Bunyan's allegorical masterpiece required him to visualize iconic scenes and characters such as Christian, Faithful, Mr. Worldly Wiseman, and the trials of Vanity Fair. His interpretations would have aimed to be faithful to the spirit of the text while bringing a new visual life to these well-known episodes. This commission reflects his high standing as an illustrator capable of handling serious and morally significant literary works.

An Artist's Studio: Exhibited at the Royal Academy, this painting likely offered a glimpse into the creative world of the artist, a subject that fascinated many Victorians. It could have depicted Watson himself, or an idealized artist, surrounded by the tools of his trade, perhaps with a model or a work in progress. Such paintings often served as reflections on the nature of art and the artist's role in society.

Exhibitions and Recognition

John Dawson Watson was a consistent exhibitor throughout his career, ensuring his work remained visible to the public and critics. His debut at the Royal Academy in 1853 marked the beginning of a long association with this premier institution. He exhibited nearly 60 works there over his lifetime, a significant achievement.

His membership in the Royal Watercolour Society (ARWS from 1864, RWS from 1869) was another important marker of his success. The RWS exhibitions were prestigious events, and his regular contributions helped to solidify his reputation as a leading watercolourist. He also showed his work at the British Institution, the Royal Society of British Artists (Suffolk Street), the Dudley Gallery, and the Grosvenor Gallery, among others. This broad range of exhibition venues indicates his active participation in the London art scene and his appeal to different segments of the art-buying public. His illustrations, by their very nature, reached an even wider audience through mass-circulation periodicals and books.

Legacy and Historical Assessment

John Dawson Watson's legacy is primarily that of a highly skilled and prolific Victorian illustrator and a charming genre painter. In the realm of illustration, he was a key figure in the "Sixties School," contributing significantly to the high artistic standards achieved in British wood-engraved illustrations during that period. His work in this field influenced subsequent generations of illustrators and helped to elevate the status of illustration as an art form. His ability to create memorable and empathetic characters, and to compose scenes with narrative clarity, made him a master of visual storytelling.

As a painter in oils and watercolours, Watson excelled in depicting scenes of domestic life, childhood, and rural charm. While he may not be as widely known today as some of the more radical innovators of his time, such as James McNeill Whistler or the later Pre-Raphaelites like Edward Burne-Jones, his work was highly regarded in his lifetime and continues to be appreciated for its technical skill, gentle sentiment, and faithful reflection of Victorian tastes and values. His paintings and watercolours are held in various public and private collections.

He successfully navigated the demands of the Victorian art market, producing work that was both popular and critically respected. His dedication to his craft, whether in the meticulous detail of a wood engraving design or the luminous washes of a watercolour, is evident throughout his oeuvre. John Dawson Watson remains an important representative of the multifaceted artistic production of the Victorian era, a period of immense creativity and change in British art.

Conclusion

John Dawson Watson's career exemplifies the diverse talents of many Victorian artists who moved adeptly between different media. From the widely disseminated wood engravings that brought stories to life for thousands of readers, to the intimately scaled watercolours and the more formal oil paintings exhibited in London's prestigious galleries, Watson consistently demonstrated a high level of craftsmanship and a sympathetic engagement with his subjects. He captured the nuances of Victorian life, its sentiments, its domestic ideals, and its literary imagination, leaving behind a body of work that offers enduring insight into the art and culture of his time. His contributions, particularly to the golden age of British illustration, secure his place as a significant and respected artist of the nineteenth century.