Marie Louise Catherine Breslau stands as a significant, though sometimes overlooked, figure in the constellation of artists who illuminated the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A painter of Swiss nationality, born in Germany and flourishing in the artistic crucible of Paris, Breslau carved out a distinguished career, particularly in portraiture, leaving behind a legacy of works celebrated for their psychological depth, exquisite handling of light, and intimate portrayal of her subjects. Her journey from a health-challenged child finding solace in art to a respected figure in the Parisian art world, a friend to luminaries like Edgar Degas, and a recipient of the French Legion of Honour, is a testament to her talent and tenacity.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Munich, Germany, on December 6, 1856, Marie Louise Catherine Breslau's early life was marked by a move to Zurich, Switzerland, following the death of her father, an accomplished obstetrician and gynecologist, when she was still a child. Her Polish mother, from a formerly wealthy Jewish family, raised her. A chronic asthma condition confined young Louise to her bed for extended periods, a circumstance that, while challenging, inadvertently steered her towards her life's passion. To while away the long hours, she began to draw, discovering not only a pastime but a profound talent and a means of expression. This early, self-directed immersion in art laid the foundation for her future endeavors.

Her formal artistic education began in Switzerland under the tutelage of a local Swiss artist, Eduard Pfyffer. However, the allure of Paris, then the undisputed capital of the art world, was strong. Recognizing the need for more advanced training and exposure to the avant-garde movements reshaping European art, Breslau, accompanied by her mother, made the pivotal decision to move to Paris in 1876. This move would place her at the heart of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, movements that would significantly inform her own artistic development.

Parisian Ascent: The Académie Julian and Salon Success

In Paris, Breslau enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian, one of the few art institutions at the time that accepted female students and offered them a curriculum comparable to that available to men, including life drawing from nude models. The Académie Julian, founded by Rodolphe Julian, became a vital training ground for many women artists and international students who found the doors of the École des Beaux-Arts closed to them. Here, Breslau studied under masters like Tony Robert-Fleury and Jules Bastien-Lepage, honing her skills in draftsmanship and composition.

Her talent quickly became apparent. She formed close bonds with fellow students, including the Russian artist Marie Bashkirtseff, whose diaries famously record a degree of rivalry and jealousy towards Breslau's prodigious abilities. Another crucial lifelong friendship forged at the Académie Julian was with Madeleine Zillhardt, who would become Breslau's companion, muse, model, and staunch supporter for over forty years.

Breslau's debut at the Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, was a significant milestone. In 1879, she became one of the first women from the Académie Julian to have her work accepted, a remarkable achievement in a male-dominated art world. This early success was followed by consistent participation in the Salon, where her portraits and genre scenes garnered critical attention.

Artistic Style, Influences, and Thematic Concerns

Breslau's artistic style is often aligned with Impressionism, yet it retains a distinct individuality. She absorbed the Impressionists' fascination with light, color, and contemporary life, but her work often demonstrates a more solid grounding in academic draftsmanship, particularly in her early career. Her brushwork could be fluid and suggestive, capturing fleeting moments and atmospheric effects, yet her figures always maintained a sense of volume and presence.

She was undoubtedly influenced by the great Impressionists such as Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, particularly in her vibrant palette and her ability to capture the play of light on surfaces. The influence of Edgar Degas, with whom she developed a friendship, can also be discerned in her candid compositions and her interest in capturing figures in unposed, naturalistic moments. Like Degas and Mary Cassatt, Breslau often focused on the lives of women, depicting them in domestic interiors, engaged in quiet activities, or in moments of shared intimacy.

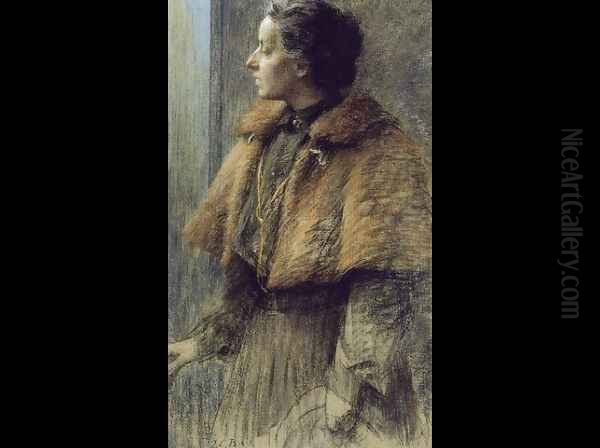

Her portraiture was particularly lauded. Breslau possessed a keen ability to capture not just the likeness of her sitters but also their inner lives and personalities. Her portraits are characterized by their sensitivity, psychological insight, and often a subtle melancholy. She painted numerous portraits of friends, fellow artists, writers, and members of Parisian society, creating a vivid gallery of the intellectual and artistic milieu of her time. Beyond oil painting, Breslau was also proficient in pastels, watercolors, and printmaking, demonstrating versatility across different media.

Key Works: Capturing Intimacy and Character

Several works stand out in Breslau's oeuvre, marking significant moments in her career and encapsulating her artistic strengths.

"Les Amies" (Friends) / "Contre-Jour" (Against the Light): Exhibited at the Salon of 1881, this painting earned Breslau an honorable mention and cemented her reputation. The work depicts two young women, one of whom is likely Madeleine Zillhardt, seated at a table in an interior, with light streaming in from a window behind them. The "contre-jour" effect, where the subjects are backlit, is masterfully handled, creating a soft, atmospheric glow and highlighting the intimacy of the scene. The painting showcases her skill in composition, her sensitive portrayal of female companionship, and her sophisticated use of light and shadow. It is considered one of her most iconic pieces.

"La Toilette" (Grooming or At Her Toilet): This theme, popular among Impressionists like Degas and Cassatt, allowed Breslau to explore the private world of women. Her depictions are typically tender and observational, focusing on the quiet rituals of daily life. These works often feature delicate color harmonies and a focus on the textures of fabric and flesh.

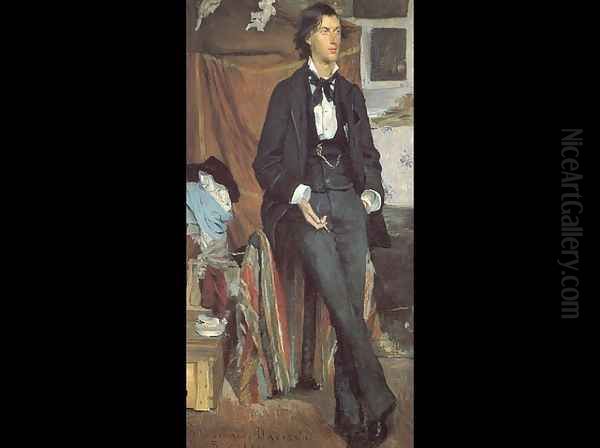

"Portrait of Henry Davison": An example of her commissioned portraiture, this work would have demonstrated her ability to capture the character of prominent individuals. Her portraits were sought after for their blend of technical skill and empathetic portrayal.

"Still Life with Columbines and Floats": While primarily known for her figure paintings, Breslau also produced accomplished still lifes. These works reveal her keen eye for detail, her understanding of color relationships, and her ability to imbue everyday objects with a sense of quiet beauty.

Her body of work often explored themes of female friendship, domesticity, and the inner lives of women. In an era when female artists were still struggling for recognition, Breslau's focus on these subjects, rendered with such skill and sensitivity, provided a valuable perspective. She also depicted children with particular tenderness, capturing their innocence and natural charm.

Friendships, Artistic Circle, and Recognition

Louise Catherine Breslau was not an isolated figure but an active participant in the vibrant artistic and intellectual life of Paris. Her friendships were numerous and significant, providing support, inspiration, and intellectual exchange.

Madeleine Zillhardt: As mentioned, Zillhardt was Breslau's lifelong companion. Their relationship was a cornerstone of Breslau's personal and artistic life. Zillhardt frequently modeled for Breslau and was a constant source of encouragement. After Breslau's death, Zillhardt worked to preserve her legacy, notably by donating many of her works to museums, including the Musée de Dieppe. Zillhardt also authored a biography of Breslau, "Louise Catherine Breslau et ses amis" (Louise Catherine Breslau and Her Friends), offering invaluable insights into her life and circle.

Edgar Degas: Breslau cultivated a friendship with the formidable Edgar Degas. Degas, known for his sharp intellect and demanding standards, respected Breslau's talent. Their association underscores Breslau's standing within the Parisian avant-garde. While direct collaborations are not extensively documented, their shared interest in capturing modern life and their presence in similar artistic circles suggest a collegial relationship.

Anatole France: Breslau also enjoyed a long and close friendship with the celebrated French writer and Nobel laureate Anatole France. This friendship, spanning some forty years, indicates Breslau's engagement with the literary world and her intellectual breadth. She painted his portrait, a testament to their mutual esteem.

Other Contemporaries: Breslau moved in a circle that included many other notable artists and writers. She would have been aware of, and likely interacted with, other prominent female Impressionists such as Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot. Though their styles and specific social circles might have differed, they shared the experience of navigating the art world as women. Other artists of the period whose work formed the backdrop to Breslau's career include Eva Gonzalès, another talented female painter associated with Manet, and Lilla Cabot Perry, an American Impressionist who also spent significant time in France. The broader Impressionist movement, with figures like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley, created the artistic climate in which Breslau thrived. Even artists from slightly different but related movements, such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec with his depictions of Parisian nightlife, or Symbolists like Odilon Redon, contributed to the rich artistic tapestry of the era. The influence of Realists like Gustave Courbet and the pioneering modernism of Édouard Manet had paved the way for the Impressionists and, by extension, for artists like Breslau.

Her talent did not go unrecognized. Breslau exhibited widely, not only in Paris but also in Brussels, London, and her native Switzerland. She received numerous accolades throughout her career. A crowning achievement was her appointment as a Chevalier of the French Legion of Honour in 1901, making her one of the first foreign-born women, and one of the first Swiss women, to receive this prestigious award. This honor signified official recognition of her significant contributions to French art.

The War Years, Later Life, and Legacy

The outbreak of World War I brought a shift in Breslau's focus. Together with Madeleine Zillhardt, she dedicated herself to patriotic efforts, producing works that depicted French soldiers and nurses, capturing the somber realities and quiet heroism of the war. These works, often in pastel or watercolor, demonstrate her continued ability to convey emotion and character even in challenging circumstances.

After the war, Breslau continued to paint, though perhaps with less public visibility than in her earlier years. She and Zillhardt spent much of their time at their country house outside Paris, where Breslau found joy in gardening. Her later works often reflect this connection to nature, featuring floral still lifes and tranquil domestic scenes.

Marie Louise Catherine Breslau passed away in Paris on May 12, 1927, after a long illness. She was buried in the town of Baden, in Aargau, Switzerland. In her will, she ensured the preservation of her artistic legacy. Madeleine Zillhardt, as her heir, faithfully carried out Breslau's wishes, donating a significant portion of her artworks and personal papers to various institutions, most notably the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dieppe and the Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts in Lausanne. This act ensured that Breslau's contributions would not be forgotten.

Despite her success during her lifetime, Breslau's name, like those of many women artists, faded somewhat from mainstream art historical narratives in the decades following her death. However, the late 20th and early 21st centuries have seen a renewed interest in her work, fueled by a broader reassessment of the contributions of women artists and a deeper appreciation for the nuances of the Impressionist era. Exhibitions and scholarly research have brought her art back into the public eye, reaffirming her place as a gifted and important painter.

Today, a street in Paris, the "Place Louise-Catherine-Breslau et Madeleine-Zillhardt" in the 6th arrondissement, commemorates both her and her lifelong companion, a fitting tribute to their intertwined lives and Breslau's artistic achievements. Her paintings are held in museum collections across Europe and the United States, admired for their technical brilliance, their intimate charm, and their insightful portrayal of the human spirit.

Breslau in the Context of Female Impressionists

When considering Louise Catherine Breslau, it is insightful to place her within the context of other female artists associated with Impressionism, such as Mary Cassatt, Berthe Morisot, and Marie Bracquemond. While each of these artists developed a unique style, they shared common challenges and opportunities. They navigated a male-dominated art world, often finding alternative venues for exhibition and support networks among fellow artists.

Like Cassatt and Morisot, Breslau often focused on themes of women, children, and domestic life. This was partly a reflection of the societal constraints placed upon women, which limited their access to the broader range of subjects available to male artists (such as café scenes or certain aspects of public life). However, these artists transformed these perceived limitations into strengths, bringing a unique sensitivity and intimacy to their depictions of the female sphere. Breslau's work, with its psychological depth and nuanced portrayal of relationships, contributes significantly to this aspect of Impressionist art.

Unlike Cassatt, who was American, or Morisot, who was French and deeply embedded in the core Impressionist group from its inception, Breslau, as a Swiss artist of German birth, brought a slightly different cultural perspective. Her training at the Académie Julian, rather than through private tutelage with established Impressionists (as was the case for Morisot with Manet, or Cassatt's close association with Degas), also shaped her trajectory. Breslau's art, while clearly Impressionistic in its concerns with light and modern life, often retained a more structured, almost classical underpinning, particularly in her portraiture, which perhaps reflects her academic training.

Conclusion: An Enduring Radiance

Marie Louise Catherine Breslau was an artist of considerable talent and quiet determination. She successfully navigated the competitive Parisian art world, achieving recognition and respect from her peers and the public. Her portraits are remarkable for their psychological acuity, her genre scenes for their intimate charm, and her overall body of work for its sophisticated handling of light, color, and composition.

Her friendships with figures like Edgar Degas, Anatole France, and especially Madeleine Zillhardt, enriched her life and art, placing her within a vibrant network of creative individuals. The honors she received, including the Legion of Honour, attest to the esteem in which she was held.

While her fame may have been eclipsed for a time, the enduring quality of her art has ensured its rediscovery. Marie Louise Catherine Breslau's legacy is that of a gifted painter who brought a unique voice to the Impressionist era, a voice that continues to resonate with viewers today through its beauty, sensitivity, and profound humanity. Her contribution to the rich tapestry of late 19th and early 20th-century art is undeniable, securing her place as a luminous talent whose work deserves continued appreciation and study.