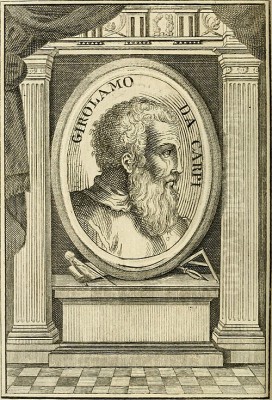

Girolamo da Carpi (1501-1556) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant tapestry of Italian Renaissance art. A native of Ferrara, his career unfolded across several key artistic centers, including Bologna and Rome, absorbing and reinterpreting the dominant styles of his era. As a painter, decorator, and architect, Carpi's versatility allowed him to contribute to both grand ducal commissions and ecclesiastical projects, leaving behind a body of work that reflects the complex artistic currents of the 16th century. His life and art offer a fascinating glimpse into the world of a provincial master navigating the influences of giants like Raphael, Correggio, and Giulio Romano, while forging his own distinct, albeit eclectic, artistic identity.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Ferrara

Born Girolamo Sellari in Ferrara in 1501, his artistic journey began under the tutelage of his father, Tommaso da Carpi, a painter and decorator of modest reputation. Initially, Girolamo was engaged in more utilitarian aspects of the workshop, such as painting chests, stools, and other decorative items. However, the young artist harbored ambitions beyond these craft-based tasks, aspiring to the more esteemed realm of figural painting. This ambition reportedly met with resistance from his father, who perhaps saw a more stable, if less glorious, future in the decorative arts.

This paternal disapproval, coupled with Girolamo's burgeoning desire to immerse himself in a more dynamic artistic environment, led him to seek opportunities elsewhere. Before venturing further afield, however, he became a student of Benvenuto Tisi, more famously known as Il Garofalo (Benvenuto di Giorgio da Lucca). Garofalo was a leading figure in the Ferrarese school, known for his Raphaelesque classicism blended with local traditions. This apprenticeship would have provided Carpi with a solid grounding in the prevailing artistic language of Ferrara, which was itself a sophisticated ducal court under the Este family, patrons renowned for their cultural discernment. The influence of other Ferrarese masters, such as Dosso Dossi, with his imaginative and often enigmatic style, would also have been part of Carpi's early visual environment.

The Bolognese Sojourn: New Influences and Collaborations

Around the age of twenty, Girolamo da Carpi made the pivotal decision to move to Bologna. This city, a papal territory with a thriving university and a rich artistic heritage, offered new avenues for learning and practice. In Bologna, he is said to have studied under Lorenzo Costa, an elder master whose career bridged the late Quattrocento and early Cinquecento, and who himself had been influenced by Ferrarese art before establishing himself in Bologna and later Mantua. Costa's workshop would have exposed Carpi to a style that balanced clarity of form with a gentle devotional sentiment.

However, it was the work of Antonio Allegri da Correggio that seems to have made the most profound impact on Carpi during his Bolognese years. Though Correggio was primarily active in Parma, his innovative style, characterized by soft sfumato, dynamic compositions, and a palpable sense of grace and movement, resonated deeply with many artists of the period. Carpi reportedly saw Correggio's painting of Christ (likely a version of Noli Me Tangere or a similar subject) and was so moved by its beauty and technical mastery that it solidified his passion for painting. He began to diligently copy Correggio's works, internalizing the Parmese master's approach to light, form, and emotional expression. This engagement with Correggio's art would become a recurring feature in Carpi's stylistic development, lending a softness and sensuality to his figures.

During his time in Bologna, Carpi also engaged in significant collaborations. He worked with Biagio Pupini (also known as Biagio dalle Lame), another Bolognese painter influenced by Raphael and Parmigianino. Together, Carpi and Pupini undertook several decorative projects. In 1525, they collaborated on the decoration of the sacristy of San Michele in Bosco, a prominent Olivetan monastery overlooking Bologna. Such collaborations were common, allowing artists to tackle large-scale commissions more efficiently and to blend their respective strengths. The experience of working alongside Pupini would have further broadened Carpi's stylistic vocabulary and practical skills in fresco and panel painting. Another artist he is noted to have worked with during this period was Giovanni Borghese (or Borghini), with whom he also decorated parts of San Michele in Bosco.

Roman Exposure and the Allure of Antiquity

The mid-1520s saw Girolamo da Carpi travel to Rome, the epicenter of the High Renaissance. This journey was a crucial rite of passage for ambitious artists, offering unparalleled opportunities to study classical antiquities and the works of the great masters who had recently transformed the city's artistic landscape. In Rome, Carpi encountered the powerful legacy of Raphael Sanzio, whose stanze in the Vatican and numerous altarpieces had set a new standard for harmony, grace, and compositional clarity. He also would have seen the monumental achievements of Michelangelo Buonarroti, particularly the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

A particularly strong influence from this Roman period was Giulio Romano. A principal pupil and collaborator of Raphael, Giulio had inherited Raphael's workshop after the master's death in 1520 and subsequently developed a more dynamic, muscular, and often emotionally charged style that prefigured Mannerism. By the time Carpi was in Rome, Giulio Romano had departed for Mantua to serve the Gonzaga court, but his powerful Roman works, such as those in the Villa Madama and Palazzo Baldassini, remained. Carpi was particularly drawn to Giulio's "Mantuan style" – a robust, often complex, and highly decorative approach that blended classical motifs with a new sense of energy and invention. This exposure to Giulio Romano's work encouraged Carpi to experiment with more elongated figures, intricate compositions, and a heightened sense of drama.

Carpi's Roman experience was not solely focused on painting. He also developed his skills as an architect and architectural draftsman. He meticulously studied and drew ancient Roman ruins and contemporary buildings, a practice common among Renaissance artists who often worked across different media. This architectural interest would serve him well in later commissions.

Return to Ferrara: Ducal Patronage and Major Works

After his formative experiences in Bologna and Rome, Girolamo da Carpi returned to his native Ferrara, his artistic vision enriched and his skills considerably honed. He found favor with the ruling Este family, renowned patrons of the arts and literature. Duke Ercole II d'Este, in particular, provided Carpi with numerous commissions, both as a painter and an architect.

For the Este court, Carpi produced a variety of works, including frescoes, altarpieces, and decorative schemes for their palaces. Among his notable religious paintings from this period are works like the Nativity of the Virgin and Child, a Madonna, and a Holy Trinity. These pieces often demonstrate a synthesis of his diverse influences: the grace of Raphael, the softness of Correggio, the compositional complexity of Giulio Romano, and the rich color palette characteristic of the Ferrarese school, as exemplified by artists like Dosso Dossi and Garofalo. He often worked alongside these Ferrarese contemporaries, including Dosso Dossi and his brother Battista Dossi, on large decorative projects for the Este.

His architectural talents were also in demand. He was involved in the decoration of the Muzzarelli residence and the Copara Palace in Ferrara. In these projects, he often collaborated with his former master, Il Garofalo (referred to in some sources also as Benvenuto da Firenze in this collaborative context), showcasing his ability to work in varied decorative styles, sometimes employing chiaroscuro effects, vibrant colors, or even imitating bronze. One specific collaboration with Garofalo mentioned is an Adoration of the Magi for the church of San Martino in Ferrara.

A significant architectural commission was his involvement in the expansion and renovation of the Castello Estense, the formidable Este fortress and ducal residence in the heart of Ferrara. This work required not only artistic skill but also a sophisticated understanding of engineering and design, further highlighting Carpi's versatility.

Architectural Interlude in Rome

Later in his career, around 1549 or 1550, Girolamo da Carpi was called back to Rome, this time primarily for his architectural expertise. He entered the service of Pope Julius III, a great patron of the arts. Carpi was appointed as an architect and was tasked with overseeing aspects of the renovation and expansion of the Belvedere in the Vatican. This was a prestigious appointment, placing him in direct contact with the papal court and its ambitious building projects. He worked alongside other prominent architects of the day, including Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola and Bartolomeo Ammannati, who were also involved in Julius III's extensive building program, most notably the Villa Giulia. This Roman sojourn further solidified his reputation as a capable architect.

Artistic Style: An Eclectic Synthesis

Girolamo da Carpi's artistic style is best described as an eclectic synthesis of the major currents of his time. He did not rigidly adhere to a single school but rather selectively incorporated elements from various masters and regional traditions.

His early Ferrarese training under Il Garofalo instilled in him a sense of classical balance and a rich, often warm, color palette. The influence of Dosso Dossi can also be discerned in a certain penchant for imaginative detail and atmospheric effects.

The Bolognese period brought the profound impact of Correggio, evident in the soft modeling of flesh, the graceful movement of figures, and the tender emotionality of his religious scenes. His figures often possess a gentle, almost lyrical quality, with smooth transitions between light and shadow, echoing Correggio's sfumato.

His Roman experiences, particularly his admiration for Giulio Romano, introduced a more Mannerist sensibility into his work. This can be seen in elongated proportions, complex and sometimes crowded compositions, and a more dynamic, even agitated, treatment of figures. He also absorbed the Roman emphasis on classical motifs and anatomical precision.

Carpi was a skilled draftsman, and his drawings, many of which survive, reveal his careful study of both antique sculpture and the works of his contemporaries. He was adept at capturing movement and expression with fluid lines. In his paintings, he often employed smooth, even layers of paint, with finely rendered details and carefully managed highlights, creating a polished surface. His work Opportunity, a large painting executed in Bologna, was praised for its vivacity, elegance, and meticulous detail.

He also explored the innovative technique of chiaroscuro woodcut, a method that used multiple blocks to create tonal gradations and a more painterly effect in prints. He is sometimes associated with Ugo da Carpi (no direct relation, despite the name), one of the pioneers of this technique in Italy, suggesting a shared interest in exploring new expressive possibilities in printmaking.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

While many of Carpi's works were part of larger decorative schemes or have uncertain attributions, several stand out:

The Adoration of the Magi (Dresden Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister): This painting is often considered one of his masterpieces, showcasing his ability to handle a complex multi-figure composition with a rich palette and expressive figures. It combines Ferrarese colorism with influences from Correggio and Parmigianino.

Pentecost (San Francesco, Rovigo): This altarpiece demonstrates his mature style, with dynamic figures and a dramatic use of light, reflecting his engagement with Mannerist tendencies.

Judith with the Head of Holofernes (Galleria Estense, Modena): A subject popular in the Renaissance, Carpi's version displays a strong female figure, rendered with a combination of grace and resolve.

Opportunity (lost, formerly Bologna): Though now lost, contemporary accounts praised this allegorical painting for its inventiveness and refined execution.

Frescoes in the Este Palaces (Ferrara): While many are lost or fragmentary, these commissions were central to his career and reputation in Ferrara. He worked on projects at the Castello Estense and various Este villas like Belriguardo, where he collaborated with Biagio Pupini on the Sala delle Vigne in 1537.

Portrait of Alfonso II d'Este (attributed, various collections): Carpi, like many court painters, likely produced portraits of his patrons. Attributed portraits show a sensitivity to character and a refined technique.

His architectural drawings, particularly those of Roman antiquities, are also highly valued and are held in collections such as the Rosenbach Museum & Library in Philadelphia and the British Museum.

Later Years, Character, and Legacy

Giorgio Vasari, in his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, provides some insights into Carpi's character. He describes Girolamo as a man of gentle disposition, highly skilled in his art, but also passionately devoted to music (he was an accomplished lute player) and romantic pursuits. Vasari suggests, with a hint of criticism, that these "pleasures of love and music" sometimes distracted Carpi from his artistic endeavors, implying he might have achieved even greater fame had he been more singularly focused.

A significant challenge marked Carpi's later life: he reportedly lost his sight around the age of 48. Despite this devastating setback, Vasari claims he continued to work, relying on his experience and perhaps the assistance of his workshop. One such late work mentioned is a fresco of Apollo and Daphne for the monastery of San Bernardino, a testament to his resilience.

Girolamo da Carpi died in Ferrara in 1556, at the age of 55. He left behind a legacy as a versatile and skilled artist who successfully navigated the complex artistic landscape of 16th-century Italy. He trained several pupils, including Bartolomeo Faccini and Ippolito Costa, ensuring the continuation of his artistic lineage in Ferrara. His work at the San Giorgio monastery's refectory was left unfinished due to his declining health and was later completed by Pellegrino Pellegrini (also known as Tibaldi).

While perhaps not reaching the towering stature of a Raphael, Titian, or Michelangelo, Girolamo da Carpi played an important role in disseminating and adapting the major artistic innovations of his time within Ferrara and Bologna. His ability to synthesize diverse influences—from the classicism of Raphael and Garofalo, the soft grace of Correggio, the dynamism of Giulio Romano, to the local traditions of Ferrara championed by artists like Dosso Dossi and Lorenzo Costa—resulted in a body of work that is both representative of its era and possessed of its own unique charm and sophistication. His collaborations with artists like Biagio Pupini and Giovanni Borghese further illustrate the interconnected nature of artistic practice during the Renaissance. His architectural contributions, particularly his work for the Este and Pope Julius III, underscore his multifaceted talents. Girolamo da Carpi remains a compelling figure, whose art reflects the rich interplay of regional styles and dominant artistic trends that characterized the Italian Renaissance.