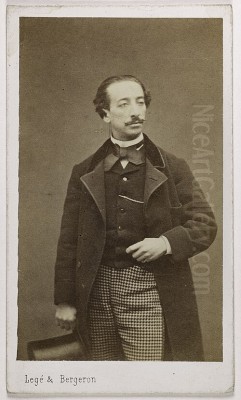

Maurice Blum stands as a fascinating figure in the landscape of 19th-century French art. A painter renowned for his meticulously detailed genre scenes and historical costume pieces, Blum captured the refined sensibilities and intimate social rituals of a bygone era. While perhaps not as globally recognized today as some of his revolutionary contemporaries, his work offers a valuable window into the tastes and artistic currents that defined the academic tradition and the popular appeal of narrative painting during the Belle Époque.

Biographical Foundations: Nationality and Early Life

Maurice Blum was born in Paris, France, in 1832. This places him squarely in the heart of a city that was, for much of the 19th century, the undisputed capital of the art world. Growing up and training in Paris provided artists with unparalleled access to esteemed institutions, influential teachers, and a vibrant, competitive artistic environment. French nationality and Parisian upbringing are central to understanding Blum's artistic trajectory, as he was immersed in the academic traditions that dominated French art education and exhibition systems for a significant portion of his career.

The precise details of his early childhood are not extensively documented, a common occurrence for artists who didn't achieve the legendary status of figures like Claude Monet or Edgar Degas. However, it's clear that he pursued formal artistic training, a prerequisite for any aspiring painter aiming for recognition within the established Salon system. This training would have emphasized drawing from classical sculpture and live models, the study of Old Masters, and the principles of composition, perspective, and anatomy.

Professional Background and Artistic Formation

Blum's professional background is that of a dedicated academic painter. He was a student of Léon Cogniet (1794-1880), a prominent historical and portrait painter who himself had studied under Pierre-Narcisse Guérin and was a respected teacher at the École des Beaux-Arts. Cogniet's influence would have instilled in Blum a reverence for technical skill, historical accuracy, and the narrative potential of painting. Artists like Cogniet were bastions of the academic tradition, upholding the hierarchy of genres that placed historical painting at the apex.

Blum's career unfolded primarily within the framework of the Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Making a debut at the Salon was a critical step for any artist seeking public recognition and patronage. Blum began exhibiting at the Salon in 1857, consistently presenting works that aligned with the prevailing tastes for polished finishes, clear storytelling, and often, a touch of historical romanticism or charming anecdote. His dedication to this path defined his professional identity.

Verifying the Chronology: Birth and Death

Confirming the exact birth and death years of historical figures, especially artists who may not have been in the absolute top tier of fame, requires careful cross-referencing of art historical records, museum archives, and biographical dictionaries. For Maurice Blum, the widely accepted and documented dates are:

Born: 1832, Paris, France

Died: 1909, Paris, France

These dates (1832-1909) place his life and productive artistic career firmly within a period of immense artistic change and upheaval in France, spanning from the July Monarchy, through the Second Republic and Second Empire, and well into the Third Republic. He witnessed the rise of Realism with Gustave Courbet, the revolutionary impact of Impressionism led by figures like Monet and Renoir, and the subsequent waves of Post-Impressionism and Symbolism.

Artistic Style: Meticulous Realism and Narrative Charm

Maurice Blum's artistic style is characterized by a meticulous, almost photographic realism in the rendering of details, particularly in fabrics, furniture, and architectural elements. He specialized in genre scenes, often set in the 17th or 18th centuries, depicting moments of polite society, intellectual pursuits, or quiet domesticity. These are often referred to as "costume pieces" or "anecdotal history" paintings, a popular genre that appealed to the bourgeoisie's fascination with the past and their appreciation for skilled craftsmanship.

His figures are typically elegant and composed, their gestures and expressions carefully calibrated to convey the narrative of the scene. Blum's palette is generally rich and harmonious, with a keen attention to the play of light and shadow that enhances the three-dimensionality of his subjects and the tactile quality of their surroundings. There's a certain intimacy and quietude in many of his works, drawing the viewer into a carefully constructed world. His approach shares affinities with the detailed genre paintings of Dutch Golden Age artists like Gerard ter Borch or Gabriël Metsu, as well as with contemporary French academic painters like Ernest Meissonier, who was renowned for his incredibly detailed small-scale historical and military scenes.

Blum's commitment to detail did not usually extend to the broader, more visible brushwork that characterized the Impressionists. Instead, his surfaces are smooth and highly finished, in keeping with academic tradition. The emphasis was on creating a believable illusion, a window onto another time, rather than on expressing the subjective experience of the artist or the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere in the manner of his avant-garde contemporaries.

Representative Works: A Glimpse into Blum's Oeuvre

Several paintings stand out as representative of Maurice Blum's style and thematic preoccupations. These works showcase his technical skill, his eye for historical detail, and his ability to craft engaging narratives.

One of his most well-known paintings is "The Art Connoisseurs" (also known as "Les Amateurs de Tableaux" or "A Collector's Cabinet"). This work, often dated to around 1890, depicts a group of gentlemen in 18th-century attire, intently examining paintings in a richly appointed interior. The scene is a celebration of art appreciation itself, filled with meticulously rendered details – the sheen of silk coats, the texture of wooden frames, the varied artworks within the artwork. It speaks to the culture of collecting and the refined taste that Blum often portrayed.

Another significant piece is "A Wedding Party" or "The Wedding Breakfast" (Le repas de noces), which captures a convivial gathering, likely from a similar historical period. Such scenes allowed Blum to display his skill in composing multi-figure arrangements and depicting a range of human interactions and emotions within a socially significant event. The attention to costume, table settings, and the expressions of the guests would have been paramount.

"The Minuet" (Le Menuet) is another characteristic work, showcasing an elegant dance scene. Here, Blum's ability to render luxurious fabrics, graceful postures, and the atmosphere of a sophisticated social gathering comes to the fore. The painting evokes the refined manners and leisure activities of the aristocracy or upper bourgeoisie of a past era.

"Card Players" (Les Joueurs de Cartes) is a theme explored by many artists, from Caravaggio to Paul Cézanne. Blum's interpretation would likely focus on the psychological interplay between the figures and the detailed depiction of their environment, again often set in a historical context. These scenes provided opportunities for subtle narrative and character study.

Other titles attributed to him, such as "The Reading," "The Music Lesson," or "A Visit to the Studio," further underscore his interest in the polite activities and intellectual pursuits of the cultured classes, often with a nostalgic glance towards the 18th century. His works are frequently found in private collections and have appeared in auctions, attesting to their enduring appeal for those who appreciate traditional genre painting.

The Parisian Art World: Contemporaries and Influences

Maurice Blum operated within a vibrant and competitive Parisian art world. His contemporaries can be broadly categorized, and understanding these groups helps situate his own artistic position.

Among the established academic painters, figures like Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904) and William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905) were titans of the Salon. Gérôme was known for his highly polished historical scenes, Orientalist subjects, and almost sculptural figures. Bouguereau excelled in mythological and allegorical paintings, as well as idealized peasant girls, all rendered with impeccable technique. Alexandre Cabanel (1823-1889) was another leading academic, famous for works like "The Birth of Venus," which was a sensation at the Salon. While Blum's subject matter was generally more intimate and less grandiose than these artists, he shared their commitment to academic finish and narrative clarity. Ernest Meissonier (1815-1891), as mentioned, was a master of meticulous detail in small-scale historical and military scenes, and his precision would have been an acknowledged standard.

The Realist movement, spearheaded by Gustave Courbet (1819-1877), had already challenged academic conventions by focusing on contemporary life and ordinary people, often on a grand scale previously reserved for history painting. While Blum's realism was one of detailed representation, it differed from Courbet's more rugged and socially conscious approach.

Most significantly, Blum's career coincided with the rise of Impressionism. Claude Monet (1840-1926), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), and Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) were revolutionizing painting with their focus on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light and color, and scenes of modern Parisian life, often painted en plein air with visible brushstrokes. Their independent exhibitions, starting in 1874, offered a direct challenge to the Salon's dominance. Blum's work, with its historical settings and smooth finish, stood in stark contrast to the avant-garde aesthetics of the Impressionists.

Later, Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), Georges Seurat (1859-1891), and Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) would push artistic boundaries even further, exploring expressive color, new compositional structures, and subjective interpretations of reality.

Within the realm of genre painting itself, artists like Jehan Georges Vibert (1840-1902) also enjoyed considerable success, particularly with his often satirical scenes of cardinals and clergy, rendered with a high degree of finish and humor. Blum's work, while equally detailed, tended towards more earnest and less overtly satirical depictions of social life.

Blum's interactions with these diverse figures are not extensively documented in terms of personal friendships or direct collaborations. However, as an active participant in the Parisian art scene and a regular Salon exhibitor, he would undoubtedly have been aware of these various artistic currents. He likely knew many of his academic colleagues and competed with them for recognition and sales. His choice to remain steadfast in his detailed, narrative style suggests a conviction in the values of academic tradition, or perhaps a pragmatic understanding of the market for such works.

Achievements and Recognition: The Salon and Beyond

Maurice Blum's primary achievements lay in his consistent success within the Paris Salon system. For an artist of his era working in a traditional style, acceptance and positive reception at the Salon were crucial markers of success. He exhibited regularly from 1857 onwards, indicating that his work met the standards of the Salon juries and found favor with the public and critics who appreciated well-crafted, engaging genre scenes.

He received official recognition for his contributions to French art. Notably, Maurice Blum was made a Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honour) in 1886. This prestigious award was a significant acknowledgment of his status and artistic merit within the French cultural establishment. Such honors were highly coveted and signified a successful career.

His paintings were acquired by private collectors and likely by some provincial museums in France, although he may not have achieved the widespread museum representation of the very top-tier academic painters or the later-canonized Impressionists. The enduring appeal of his work is evident in its continued presence in the art market, where his paintings are sought after by collectors who appreciate the charm, historical detail, and technical finesse of 19th-century genre painting.

While the avant-garde movements ultimately reshaped the course of art history, artists like Blum played an important role in satisfying the tastes of a significant segment of the art-buying public and upholding the standards of craftsmanship valued by the Academy. His achievement was to create a body of work that was both technically accomplished and narratively engaging, providing a pleasing and sophisticated visual experience for his audience.

Anecdotes and the Artist's Life

Specific, colorful anecdotes about Maurice Blum's personal life or studio habits are not as readily available as they are for more flamboyant or extensively documented artistic personalities of his time. He appears to have been a diligent and professional artist, dedicated to his craft, rather than a figure known for dramatic public pronouncements or eccentric behavior.

However, we can infer certain aspects of his life from his chosen subject matter. His fascination with 17th and 18th-century interiors, costumes, and social customs suggests a keen interest in history and material culture. To achieve the level of detail present in his paintings, he would have likely engaged in considerable research, perhaps studying historical garments, furniture, and engravings. He may have owned a collection of period props and costumes, or had access to such collections.

The life of a successful Salon painter in 19th-century Paris would have involved a disciplined studio practice. This included sketching, compositional studies, and the meticulous execution of the final canvas. Patronage was crucial, and artists like Blum would have cultivated relationships with dealers and private collectors. His studio would have been a place of work but also potentially a space to receive clients and showcase his latest creations.

The art world of Paris was a relatively close-knit community, especially within specific circles like the academic painters. It's probable that Blum socialized with fellow artists, critics, and collectors who shared his artistic sensibilities. Discussions about art, technique, exhibitions, and the changing tastes of the public would have been commonplace.

While grand adventures or scandalous episodes might not define his biography, the consistent production of high-quality, detailed paintings over several decades points to a life of focused artistic endeavor and a quiet dedication to his chosen genre. His death in 1909 marked the end of a long career that spanned a period of profound transformation in the art world.

Critical Reception and Lasting Influence

During his lifetime, Maurice Blum enjoyed positive critical reception from conservative critics who valued academic skill, historical accuracy, and pleasing subject matter. His paintings would have been praised for their charm, elegance, meticulous finish, and the way they transported viewers to a refined past. The Legion of Honour awarded in 1886 is a testament to this official and critical esteem.

However, as the 19th century progressed, the critical discourse in art began to shift. The rise of Impressionism and subsequent avant-garde movements brought new criteria for evaluating art. Critics who championed modernism often dismissed academic painting as old-fashioned, overly sentimental, or lacking in originality and personal expression. Consequently, the reputations of many Salon painters, including Blum, declined in the early 20th century as art history narratives increasingly focused on the innovators who broke from tradition.

In more recent decades, there has been a scholarly and curatorial re-evaluation of 19th-century academic art. Art historians now recognize the technical skill, cultural significance, and popular appeal of these artists. While Blum may not have been a revolutionary innovator who changed the course of art history in the way that Manet or Cézanne did, his work is valued for what it is: exquisitely crafted genre scenes that offer insight into the tastes and aspirations of his era.

His influence is perhaps most keenly felt in the continuation of traditional narrative painting and in the appreciation for historical detail in art. His paintings serve as valuable historical documents in their own right, meticulously recording (or romantically re-imagining) the costumes, interiors, and social customs of past centuries. For collectors and enthusiasts of 19th-century European art, Blum's work retains its charm and appeal due to its high level of craftsmanship and its evocative power. He remains a respected, if perhaps secondary, figure within the broader school of French academic and genre painting.

Conclusion: Maurice Blum's Enduring Place

Maurice Blum carved out a distinguished career as a painter of elegant and meticulously detailed genre scenes. A product of the French academic tradition and a consistent exhibitor at the Paris Salon, he achieved notable success and official recognition in his lifetime. His depictions of 17th and 18th-century social life, art connoisseurship, and intimate moments resonate with a charm and technical finesse that continue to attract admirers.

While the seismic shifts brought about by Impressionism and modernism later overshadowed many academic painters of his generation, Blum's work remains a testament to the enduring appeal of narrative painting and skilled craftsmanship. He provides a valuable glimpse into the artistic tastes of the Belle Époque and the refined worlds he so carefully constructed on canvas. His paintings, though perhaps not at the forefront of art historical narratives focused on radical innovation, hold their own as beautifully executed examples of a genre that delighted audiences for decades and continues to offer a window onto a gracefully imagined past. Maurice Blum, the Parisian chronicler of bygone elegance, thus retains his quiet but significant place in the rich tapestry of 19th-century art.