The 19th century in France was a period of profound artistic transformation, a dynamic era where established traditions clashed and coexisted with revolutionary new visions. Within this vibrant milieu, numerous artists contributed to the rich tapestry of French painting. Among them was Edme-Émile Laborne, a painter who, while perhaps not achieving the household-name status of some of his more avant-garde contemporaries, carved out a niche for himself with his charming and meticulously rendered scenes of Parisian life and intimate domesticity. His work offers a window into the tastes and sensibilities of a particular segment of society during the latter half of the century, a period often referred to as the Belle Époque.

Understanding Laborne requires situating him within the artistic currents of his time. He was active during a period that saw the dominance of the Académie des Beaux-Arts and its official Salon, the rise of Realism, the explosion of Impressionism, and the subsequent waves of Post-Impressionism. Laborne's art, from what can be gathered, largely aligned with the more traditional, academic, or Salon-favored styles, focusing on genre scenes, portraits, and depictions of elegant social life, executed with a polished technique.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in a Changing Paris

Edme-Émile Laborne was born in Paris on January 20, 1837, and passed away in the same city on June 12, 1913. His lifespan placed him squarely in the heart of one of the most artistically fertile periods in French history. Growing up in Paris, he would have been immersed in a city that was not only the political and economic capital of France but also the undisputed center of the Western art world. The city itself was undergoing massive transformations under Baron Haussmann, with new boulevards, parks, and buildings reshaping the urban landscape and, consequently, the experiences of its inhabitants.

Laborne's formal artistic training was significant. He was a student of two notable figures: Charles Gleyre and Hippolyte Flandrin. Gleyre (1806-1874), a Swiss-born artist who taught in Paris, was known for his academic style, often depicting mythological or historical subjects. Interestingly, Gleyre's studio also attracted students who would later become pioneers of Impressionism, such as Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Frédéric Bazille. This connection, however, does not imply Laborne followed their path; rather, it highlights the diverse talents emerging from such ateliers. Gleyre's teaching emphasized strong drawing and composition, foundational skills valued in academic art.

Hippolyte Flandrin (1809-1864), Laborne's other master, was a prominent Neoclassical painter, himself a student of the great Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Flandrin was highly regarded for his religious paintings and portraits, characterized by their linear precision, smooth finish, and restrained emotion. Training under Flandrin would have further instilled in Laborne the principles of academic draftsmanship, careful modeling of form, and a respect for the classical tradition. This educational background would have prepared Laborne well for a career within the established Salon system.

The Parisian Art World: The Salon and Emerging Alternatives

To appreciate Laborne's career, one must understand the institution of the Paris Salon. Organized by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, the Salon was the official, state-sponsored art exhibition. For much of the 19th century, it was the primary venue for artists to display their work, gain recognition, attract patrons, and secure commissions. Success at the Salon could make an artist's career. The juries, typically composed of conservative Académie members, favored historical, mythological, religious, and allegorical subjects, as well as portraits, all executed with a high degree of technical polish and adherence to academic conventions. Artists like William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Alexandre Cabanel, and Jean-Léon Gérôme were masters of this style and enjoyed immense popularity and official acclaim.

However, the mid-19th century also witnessed growing dissatisfaction with the Salon's exclusivity and aesthetic conservatism. Gustave Courbet, a leading figure of the Realist movement, challenged the academic hierarchy of subjects by depicting ordinary people and scenes of rural life on a grand scale, famously setting up his own "Pavilion of Realism" in 1855 after works were rejected by the Exposition Universelle. Jean-François Millet, another Realist, imbued his paintings of peasant life with a profound dignity, as seen in works like "The Gleaners."

By the 1860s and 1870s, the Impressionists began to emerge, further challenging the status quo. Artists like Monet, Renoir, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, and Berthe Morisot sought to capture fleeting moments and the effects of light and atmosphere, often painting en plein air (outdoors). Their looser brushwork, vibrant palettes, and focus on contemporary urban and suburban life were initially met with ridicule by critics and the public accustomed to the Salon's polished naturalism. Their independent exhibitions, starting in 1874, marked a decisive break from the Salon system.

Laborne's Career: Navigating the Salon System

Edme-Émile Laborne appears to have navigated his career primarily within the framework of the Salon. He began exhibiting at the Paris Salon in 1863 and continued to do so regularly for many years, showcasing genre scenes and portraits. This indicates a degree of acceptance by the Salon juries and an alignment with prevailing tastes, or at least a skillful adaptation to them. His chosen subjects – scenes of everyday life, often featuring elegant women and children in domestic or leisurely settings – were popular among the bourgeois clientele who frequented the Salon.

While specific awards or major state commissions for Laborne are not widely documented in easily accessible sources, consistent acceptance into the Salon over several decades was, in itself, a measure of professional success and recognition. His work would have been seen by thousands of visitors, critics, and potential buyers. He was part of a large cohort of skilled painters who catered to a market that appreciated well-crafted, pleasing images that reflected contemporary life or offered charming, idealized visions of it. These artists, sometimes referred to as "pompiers" (a somewhat derogatory term for academic artists) or simply Salon painters, formed the backbone of the official art world.

Other artists working in similar veins, depicting genre scenes with varying degrees of academic finish or anecdotal charm, included figures like James Tissot, known for his elegant portrayals of fashionable society in Paris and London, and Alfred Stevens, a Belgian painter celebrated for his sophisticated images of Parisian women in luxurious interiors. While their styles and levels of international fame differed, they shared an interest in capturing the nuances of modern life, albeit often through a refined and somewhat idealized lens.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

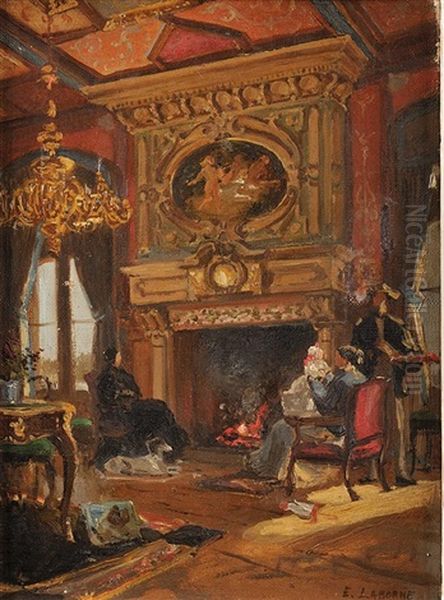

Laborne's artistic style, as suggested by his training and the nature of his exhibited works, would likely have been characterized by careful draftsmanship, a smooth, polished finish, and meticulous attention to detail, particularly in the rendering of fabrics, interiors, and figures. This was the hallmark of academic training and was highly valued by Salon juries and patrons. His compositions were likely well-balanced and harmonious, designed to create a pleasing and easily legible narrative or mood.

His thematic concerns revolved around genre painting – scenes of everyday life. This genre had a long and distinguished history in European art, from Dutch Golden Age painters like Johannes Vermeer and Pieter de Hooch to 18th-century French artists like Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin. In the 19th century, genre painting remained immensely popular, offering relatable narratives, sentimental appeal, or glimpses into different social strata.

Laborne's focus seems to have been on the more comfortable and elegant aspects of contemporary life. His paintings often depicted women and children in domestic settings, engaged in leisurely pursuits such as reading, music, or quiet contemplation. These scenes catered to a bourgeois sensibility that valued domesticity, refinement, and the portrayal of an ordered, harmonious world. The depiction of children was a particularly popular subgenre, appealing to sentimental values.

Notable Works: Glimpses into Laborne's Oeuvre

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné of Laborne's work might be elusive, some specific titles provide insight into his artistic output. Two such works mentioned are "Ein Sommernachmittag im Park" (A Summer Afternoon in the Park) and "Un dimanche en famille" (A Sunday with Family).

"Ein Sommernachmittag im Park," described as an oil on canvas measuring 33.5 x 24.9 cm and located in a German private collection, evokes a common theme in 19th-century art. Parks and public gardens became important spaces for leisure and social interaction in rapidly growing cities like Paris. Artists from Manet (e.g., "Music in the Tuileries Garden") to Renoir (e.g., "Moulin de la Galette," set in an outdoor dance hall) captured these scenes of modern life. Laborne's interpretation would likely have focused on a more serene and genteel gathering, perhaps featuring well-dressed figures enjoying a pleasant day outdoors, rendered with his characteristic attention to detail and pleasing composition. The relatively small size suggests it might have been an intimate piece intended for a domestic setting.

"Un dimanche en famille," measuring 10.6 x 7.7 cm, signed lower right, and noted as being well-preserved, points to another quintessential 19th-century bourgeois theme: the family. The small dimensions suggest a very intimate work, perhaps a cabinet picture or even a study. The title itself conjures images of a peaceful domestic scene, reinforcing Laborne's interest in the private lives and gentle pastimes of his subjects. Such works resonated with contemporary ideals of family life and provided a comforting, relatable vision for viewers.

Other titles that appear in auction records and art databases associated with Edme-Émile Laborne include "Le Billet Doux" (The Love Letter), "La Leçon de Musique" (The Music Lesson), and "Jeune femme à sa toilette" (Young Woman at Her Toilette). These titles further reinforce his preoccupation with intimate genre scenes, often centered on female figures and domestic activities. "Le Billet Doux" suggests a narrative of romance and sentiment, a popular trope in genre painting. "La Leçon de Musique" implies a scene of education and refinement, often featuring children or young women. "Jeune femme à sa toilette" belongs to a long tradition of depicting women in their private chambers, a theme explored by artists from Titian to Degas, though Laborne's approach would likely have been more modest and decorative than the psychological explorations of some of his contemporaries.

These works, characterized by their polished execution and charming subject matter, would have found a ready market among the middle and upper classes who sought art that was both aesthetically pleasing and reflective of their values and lifestyle. They offer a contrast to the more challenging or socially critical works of Realists or the radical formal innovations of the Impressionists.

Laborne in Context: Contemporaries and Comparisons

Placing Laborne within the broader spectrum of 19th-century art helps to define his position. He was not an innovator in the mold of Courbet, Manet, Monet, or Paul Cézanne. Instead, he belonged to a substantial group of highly skilled artists who worked within, or adapted to, the prevailing academic traditions and market demands. His art can be seen as part of a continuum of genre painting that flourished throughout the century.

His teachers, Gleyre and Flandrin, connected him to the lineage of Ingres and the Neoclassical tradition, emphasizing line and form. However, his subject matter – contemporary genre scenes – aligned him more with artists who focused on modern life, though his approach was likely more idealized and less gritty than that of the Realists.

Compared to the Impressionists, who were his exact contemporaries, Laborne's style would have appeared more conventional. While Monet and Renoir were capturing the fleeting effects of light with broken brushwork and vibrant color, Laborne was likely producing carefully finished canvases with smooth surfaces and a more subdued, naturalistic palette. Yet, they sometimes shared similar subjects: leisure, urban life, and domestic scenes. The difference lay in the artistic intention and execution – the Impressionists sought to convey a subjective visual experience, while Salon painters like Laborne aimed for a more objective, polished representation.

One might also consider him in relation to other European genre painters of the period, such as the German artist Carl Spitzweg, known for his humorous and anecdotal scenes, or the Biedermeier painters of Germany and Austria, who depicted cozy domestic interiors and sentimental subjects. While national characteristics differed, there was a widespread taste for genre painting across Europe in the 19th century.

Within France itself, artists like Ernest Meissonier achieved enormous success with meticulously detailed historical genre scenes, often on a small scale. While Laborne's subjects were contemporary rather than historical, a similar emphasis on craftsmanship and narrative clarity might be found. The works of artists like Jehan Georges Vibert, known for his satirical paintings of cardinals, also demonstrate the popularity of anecdotal genre scenes with a high degree of finish.

Later Career and Legacy

Edme-Émile Laborne continued to paint and exhibit throughout his career, adapting to the evolving tastes of the art market to some extent, though likely remaining true to his core style rooted in academic training. He lived through the Belle Époque, a period of optimism and cultural flourishing in Paris, and his art reflects the elegance and refined sensibilities often associated with this era.

His death in 1913 occurred just before the outbreak of World War I, an event that would irrevocably change European society and, with it, the art world. By the early 20th century, modern art movements such as Fauvism, Cubism (led by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque), and Expressionism had already taken center stage, pushing the boundaries of artistic representation far beyond what the 19th-century Salon would have countenanced.

In the grand narrative of art history, which often prioritizes innovation and avant-gardism, artists like Edme-Émile Laborne can sometimes be overlooked. He was not a revolutionary figure who dramatically altered the course of art. However, his work holds value for several reasons. Firstly, it represents a significant and popular stream of artistic production in the 19th century. The Salon painters, despite later criticism, were highly skilled and catered to the tastes of a large segment of the population. Their work provides insight into the cultural values, social aspirations, and aesthetic preferences of their time.

Secondly, Laborne's paintings, with their charming depictions of domestic life, leisure, and childhood, contribute to our understanding of 19th-century Parisian society, particularly the bourgeois milieu. They are visual documents, albeit idealized ones, of a bygone era.

Today, works by Laborne and similar Salon painters appear periodically on the art market, often appreciated for their technical skill, decorative qualities, and nostalgic charm. While they may not command the astronomical prices of Impressionist masterpieces, there is a steady interest among collectors who value this type of 19th-century academic and genre painting. Museums also hold examples of such work, recognizing its importance in providing a complete picture of the artistic landscape of the period. Artists like Giovanni Boldini or Paul César Helleu, who specialized in society portraits, also captured the elegance of this era, though often with a more flamboyant touch than Laborne's quieter genre scenes.

Conclusion: A Painter of His Time

Edme-Émile Laborne was a product of his time and training – a Parisian artist who skillfully navigated the established art world of the 19th century. Rooted in the academic tradition through his studies with Gleyre and Flandrin, he developed a refined style well-suited to the genre scenes and portraits that found favor at the Paris Salon. His paintings, such as "Ein Sommernachmittag im Park" and "Un dimanche en famille," offer intimate and charming glimpses into the lives of the Parisian bourgeoisie, characterized by meticulous detail, pleasing compositions, and a gentle, often sentimental, mood.

While the seismic shifts brought about by Realism, Impressionism, and subsequent modernist movements often dominate discussions of 19th-century art, it is important to remember the rich and diverse artistic production that existed alongside these avant-garde currents. Laborne and his many Salon colleagues played a vital role in the cultural life of their era, creating art that was admired, collected, and enjoyed by a wide audience. His work serves as a valuable reminder of the multifaceted nature of art history and the enduring appeal of well-crafted images that capture the nuances of human experience, however quietly or conventionally. He remains a representative figure of a particular strand of 19th-century French painting, a chronicler of intimate moments and the understated elegance of Parisian life.