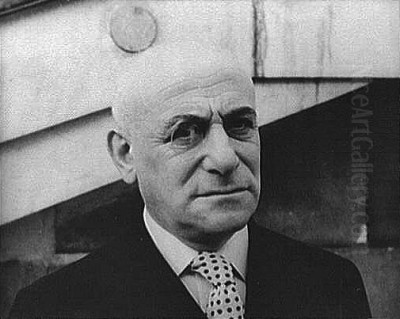

Max Jacob stands as one of the most fascinating, multifaceted, and ultimately tragic figures of early 20th-century Parisian modernism. A poet, painter, novelist, critic, and mystic, Jacob was a vital catalyst in the artistic ferment of Montmartre and Montparnasse. His life was a tapestry woven with threads of profound creativity, spiritual searching, deep friendships with artistic giants, and a heartbreaking end under the shadow of Nazi persecution. To understand Max Jacob is to delve into the heart of an era that redefined art and literature.

Early Life and Arrival in Paris

Cyprien Max Jacob was born on July 12, 1876, in Quimper, Brittany, into a family of non-observant German Jewish tailors. His early years were marked by a complex blend of experiences, reportedly oscillating between parental neglect and intense affection, which may have contributed to a sensitive and somewhat unstable temperament. This inner turmoil manifested in several reported suicide attempts during his adolescence, hinting at the profound existential questions that would later fuel his artistic and spiritual quests.

In 1894, at the age of eighteen, Jacob left the provincial confines of Quimper for the magnetic pull of Paris. He initially pursued various odd jobs, including law clerk, art critic, and even piano tutor, to sustain himself. However, his true calling lay within the burgeoning bohemian circles of the capital. He quickly gravitated towards Montmartre, the hilltop village that was then the epicenter of avant-garde artistic and literary activity.

The Crucible of Montmartre: Friendships and Artistic Ferment

Montmartre in the early 1900s was a melting pot of revolutionary ideas and artistic experimentation. It was here that Jacob’s path fatefully intersected with that of a young Spanish painter who would become his closest friend and a defining figure of modern art: Pablo Picasso. They met around 1901, and Jacob, older and more established in Parisian life, took Picasso under his wing, helping him learn French and navigate the city's cultural landscape. For a time, they shared a cramped room in a dilapidated building on Boulevard Voltaire, an experience that forged an indelible bond.

This friendship was pivotal. Jacob introduced Picasso to the influential poet and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire, another towering figure of the avant-garde. Apollinaire, in turn, would later introduce Picasso to Georges Braque. This network of relationships, with Jacob often acting as a quiet connector, was instrumental in the cross-pollination of ideas that led to the birth of Cubism. Jacob, Picasso, and Apollinaire formed a core trio, often found debating art and life in the smoky cafes and studios of Montmartre.

Jacob's circle extended beyond these luminaries. He was a familiar and respected figure in the Bateau-Lavoir, the legendary Montmartre tenement building that housed Picasso, Juan Gris, Kees van Dongen, and later Amedeo Modigliani, among others. Jacob himself lived there for a period. He was also acquainted with artists like Henri Matisse, though their artistic paths diverged, and the Montmartre painters Maurice Utrillo and Suzanne Valadon. His wit, erudition, and eccentric charm made him a welcome presence in these artistic gatherings.

Jacob the Poet: Innovator of the Prose Poem

While Jacob was a painter of considerable talent, his most enduring legacy arguably lies in his poetry. He was a pioneer of the modern prose poem, a form he imbued with a unique blend of irony, fantasy, colloquial language, and profound spiritual yearning. His most celebrated collection, Le Cornet à dés (The Dice Cup), published in 1917, is a landmark of modernist literature.

Le Cornet à dés eschews traditional narrative and lyrical structures, opting instead for fragmented, dreamlike vignettes that capture the absurdity and fleeting beauty of modern life. The poems are often humorous, self-deprecating, and filled with surprising juxtapositions, reflecting Jacob's complex personality and his keen observation of the Parisian demimonde. This work influenced a generation of poets, including the Surrealists, though Jacob himself maintained a certain distance from organized movements.

Another significant early literary work was Saint Matorel, published in 1911 with illustrations by Picasso. This mystical and autobiographical novel recounts the spiritual visions and struggles of its protagonist, reflecting Jacob's own burgeoning religious preoccupations. His literary output also includes Le Laboratoire central (The Central Laboratory, 1921), further showcasing his experimental approach to narrative and language, and numerous other collections of poems, critical essays, and correspondence that reveal the breadth of his intellectual engagement. His style, often termed "literary Cubism," mirrored the fragmented perspectives and multiple viewpoints of Cubist painting.

Jacob the Painter: A Cubist Sensibility

Max Jacob's visual art, though perhaps less widely known than his poetry, is integral to understanding his creative output. He was an early and enthusiastic participant in the Cubist adventure, deeply influenced by his close association with Picasso and Braque. His paintings and gouaches often feature the characteristic fractured planes, muted palettes, and geometric deconstruction of figures and objects typical of early Cubism.

He exhibited his artwork alongside other avant-garde painters and contributed to the theoretical discussions surrounding the new movement. Works like La Côte (The Coast, 1913) demonstrate his engagement with Cubist principles. His visual art, much like his poetry, often carried an undercurrent of whimsy, mysticism, and a deeply personal symbolism. He painted scenes of Parisian life, Breton landscapes, and imaginative, almost folkloric compositions.

While he never achieved the same level of fame as a painter as Picasso or Braque, his artistic contributions were recognized by his contemporaries. His visual work was not confined to Cubism; he also explored styles that touched upon Expressionism and a pre-Surrealist sensibility, evident in works like Vache dans un paysage (Cow in a Landscape, 1920). His drawings, often delicate and imbued with a subtle humor, are particularly noteworthy. He also collaborated with other artists, such as Manolo Hugué, a Catalan sculptor and friend of Picasso, with whom Jacob spent time in Céret.

Spiritual Quest and Conversion

A defining aspect of Max Jacob's life and work was his profound and often tormented spirituality. Born Jewish, he experienced a powerful mystical vision of Christ on the wall of his modest room in September 1909. This event, which he described in detail, marked a turning point in his life. He began a period of intense spiritual seeking and instruction, eventually leading to his decision to convert to Catholicism.

His baptism took place on February 18, 1915, with Pablo Picasso surprisingly agreeing to be his godfather. This choice of godfather underscores the complex, enduring, and sometimes paradoxical nature of their friendship. Jacob adopted the baptismal name Cyprien, in honor of Saint Cyprian of Carthage. His conversion was not a simple affair; it was fraught with inner conflict, doubt, and a continued wrestling with his Jewish heritage, his Breton roots, his Parisian identity, and his homosexuality, which the Church condemned.

This spiritual journey profoundly influenced his writing and art. Religious themes, mystical experiences, and a preoccupation with sin, redemption, and the divine became increasingly prominent in his work. However, his faith was not one of serene acceptance but rather a dynamic, often anguished, engagement with the sacred. His works often blend the sacred and the profane, the sublime and the ridiculous, reflecting his unique spiritual sensibility.

Identity and Contradictions

Max Jacob's life was a study in contradictions. He was a Jew who became a devout Catholic, a Breton deeply attached to his regional identity yet a quintessential Parisian bohemian, a homosexual man striving for spiritual purity within a faith that condemned his orientation. He was an artist celebrated for his wit and irony, yet plagued by periods of deep melancholy and spiritual anxiety.

These complex layers of identity fueled his creativity but also contributed to his personal struggles. He sought to reconcile these disparate elements through his art and his faith, but the tension often remained. His writings frequently explore themes of identity, alienation, and the search for meaning in a fragmented world. He was a figure who embodied the anxieties and aspirations of the modern individual, grappling with tradition and innovation, faith and doubt, belonging and otherness. His friendships with figures like Jean Cocteau, another artist navigating complex identities, further highlight this aspect of his life.

Later Years: Retreat and Gathering Storm

From the 1920s onwards, Jacob increasingly sought refuge from the bustle of Paris, spending long periods in the Benedictine monastery of Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire. He lived a semi-monastic life, dedicating himself to prayer, painting, and writing, though he never formally took vows. This retreat was partly a spiritual quest and partly a way to manage his often precarious financial situation and his inner turmoil. He continued to correspond with friends like Picasso, Apollinaire (until his death in 1918 from the Spanish Flu), and younger artists and writers who sought his guidance, including the poet Pierre Reverdy.

Despite his retreat, he was not entirely isolated. He received the Légion d'honneur in 1932, a mark of official recognition for his contributions to French culture. However, the political climate in Europe was darkening. With the rise of Nazism in Germany and the increasing anti-Semitism in France, Jacob's Jewish origins placed him in growing danger.

The Tragic End: Drancy

Following the German occupation of France in 1940, the Vichy regime implemented anti-Jewish laws. Despite his conversion to Catholicism and his prominent position in French letters, Max Jacob was not spared. His sister, brother-in-law, and other relatives were arrested and deported. Friends, including Picasso and Cocteau, reportedly tried to intervene or offer help, but the machinery of persecution was relentless.

On February 24, 1944, Max Jacob was arrested by the Gestapo in Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire. He was initially imprisoned in Orléans and then transferred to the Drancy internment camp, a transit point for French Jews being sent to Auschwitz and other extermination camps. The conditions in Drancy were horrific. Weakened by illness (variously reported as pneumonia or tuberculosis) and the brutal environment, Max Jacob died in the camp infirmary on March 5, 1944, at the age of 67. His death, just months before the liberation of Paris, was a tragic loss for French culture.

Legacy and Art Historical Evaluation

Max Jacob's legacy is complex and continues to be re-evaluated. For a long time, his fame was somewhat overshadowed by that of his more celebrated contemporaries like Picasso or even Modigliani. Some critics found his work too eclectic, too difficult to categorize, a "chaotic mixture" as some early commentators put it. His relationship with Picasso, while undeniably close, has also been subject to varied interpretations, with some seeing it as a pure friendship and others as a more competitive and sometimes strained dynamic.

However, his importance as a precursor to Surrealism (though he was never formally a member of André Breton's group) and as a key figure in the development of modern poetry is now widely recognized. Le Cornet à dés remains a seminal text, admired for its formal innovation and its unique voice. His paintings and drawings, once considered secondary to his literary output, have also gained greater appreciation for their charm, skill, and their connection to the Cubist aesthetic.

The fusion of Jewish, Breton, Parisian, and Catholic elements in his work gives it a distinctive richness. His life and art offer profound reflections on identity, faith, suffering, and the role of the artist in society. He was a bridge figure, connecting different artistic and literary currents, and his influence, though sometimes subtle, can be traced in the work of many later writers and artists. The tragedy of his death in Drancy adds a poignant dimension to his story, making him a martyr of artistic freedom and a victim of one of history's darkest chapters.

Conclusion

Max Jacob was more than just a poet or a painter; he was a cultural catalyst, a spiritual seeker, and a profoundly human artist whose life mirrored the creative upheavals and tragic conflicts of his time. From the vibrant studios of the Bateau-Lavoir to the solemn cloisters of Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire, and finally to the despair of Drancy, his journey was one of relentless artistic exploration and an unyielding search for meaning. His works, imbued with humor, pathos, and a unique visionary quality, continue to resonate, securing his place as an indispensable, if sometimes enigmatic, figure in the pantheon of modern art and literature. His life serves as a testament to the resilience of the creative spirit and a somber reminder of the human cost of intolerance.