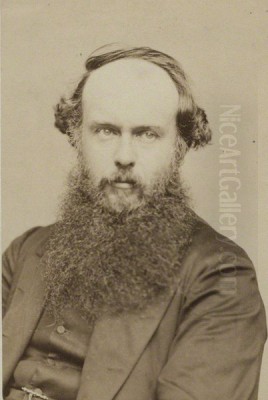

Myles Birket Foster stands as one of the most beloved and prolific artists of the Victorian era in Britain. Renowned primarily for his idyllic watercolours and detailed illustrations depicting the English countryside, Foster captured a vision of rural life that resonated deeply with his contemporaries and continues to charm audiences today. His career spanned the transition from wood engraving and illustration to fine art painting, making him a significant figure in the artistic landscape of the 19th century.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Born on February 4, 1825, in North Shields, then part of Northumberland (now Tyne and Wear), Myles Birket Foster hailed from a devout Quaker family. He was one of several children born to Myles Birket Foster Sr. and Ann King. His father was a successful businessman who co-founded M. B. Foster & Sons, a prominent beer-bottling company that grew into one of the largest of its kind globally. Despite the family's commercial success, young Myles showed little interest in the brewing trade.

In 1830, the Foster family relocated to London, providing the young artist with greater exposure to the cultural heart of the nation. His formal education took place first at Grove House School in Tottenham and later at Isaac Brown's Academy, a Quaker school in Hitchin, Hertfordshire. From an early age, Foster displayed a clear aptitude for drawing and a burgeoning passion for art, initially aspiring to become a landscape painter.

A pivotal moment occurred when Foster was sixteen. A serious accident, the details of which are scarce but described as nearly fatal, curtailed his initial ambitions. Concerned for his son's well-being and recognizing his artistic inclinations, his father sought a safer, art-related profession for him. This led to an apprenticeship opportunity that would shape Foster's early career significantly.

Apprenticeship and the World of Illustration

In 1841, Foster was apprenticed to Ebenezer Landells, a prominent wood engraver and illustrator who had himself been a pupil of the famous Thomas Bewick. Landells was also instrumental in founding the satirical magazine Punch. Initially tasked with the technical aspects of wood engraving, Foster's talent for drawing quickly became apparent to Landells.

Landells astutely shifted Foster's focus from cutting blocks to drawing original designs directly onto the wood for others to engrave. This experience proved invaluable, honing Foster's skills in composition, detail, and narrative clarity – essential qualities for an illustrator. During his time with Landells, Foster contributed numerous illustrations to Punch and the rapidly growing Illustrated London News, the world's first illustrated weekly newspaper.

After completing his apprenticeship around 1846, Foster established himself as an independent illustrator. His reputation grew rapidly, and he became highly sought after by publishers and authors. He possessed a remarkable ability to translate text into evocative visual imagery, making him a favourite for illustrating poetry and gift books, which were immensely popular during the Victorian period.

His illustrative work graced the pages of numerous volumes, including editions of poems by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (such as Evangeline, Voices of the Night, and Hyperion), Sir Walter Scott, Oliver Goldsmith, Thomas Gray, and John Milton. He also provided illustrations for editions of Shakespeare. His delicate and detailed style perfectly suited the often sentimental or pastoral themes of the literature he illustrated.

Foster collaborated extensively with other key figures in the burgeoning illustration market. He worked closely with the renowned colour printer and wood engraver Edmund Evans, who was pioneering new methods for colour printing illustrations. Their collaborations resulted in beautifully produced books that were highly prized. He also frequently worked with the Dalziel Brothers, George and Edward, who ran one of the largest and most respected wood-engraving firms in London, engraving works by many leading artists of the day, including Pre-Raphaelites like John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Foster's relationship with publisher and engraver Henry Vizetelly was also significant, with Vizetelly recognizing and promoting Foster's talent early on, despite potential professional rivalry.

The Transition to Watercolour

While illustration brought Foster considerable success and financial stability, his underlying passion remained painting, particularly landscape painting in watercolour. By the late 1850s, having established a strong reputation and likely seeking greater artistic freedom, Foster began to dedicate more of his time to watercolour painting, gradually phasing out his illustrative work.

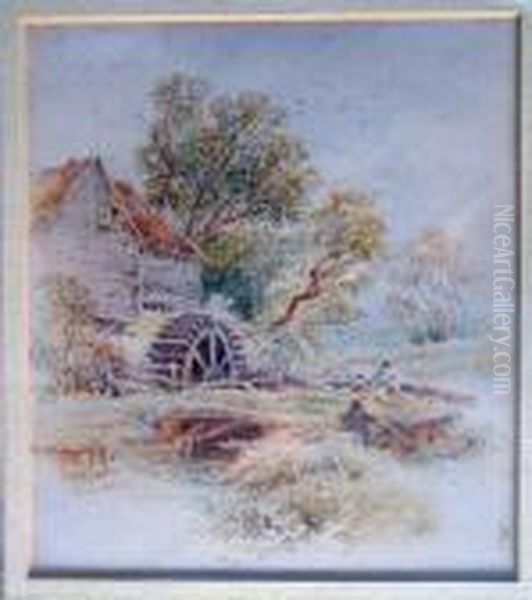

This transition marked a significant shift in his career. He taught himself the techniques of watercolour, developing a distinctive style characterized by meticulous detail and a unique method of execution. Rather than using broad washes of colour, typical of earlier watercolourists like David Cox or Peter De Wint, Foster often employed a technique involving fine stippling – applying colour in tiny dots or short strokes using a relatively dry brush.

This stippling method allowed him to achieve a high degree of finish, texture, and luminosity, particularly effective in rendering the intricate details of foliage, flowers, and rustic textures. It gave his watercolours an almost jewel-like quality and enabled him to work on a larger scale than was common for the medium at the time. His technical approach set him apart from many contemporaries and contributed to the unique appeal of his work.

His dedication to the medium was recognized in 1860 when he was elected an Associate of the prestigious Society of Painters in Water Colours (often known as the "Old Watercolour Society" or OWS). He became a full member just two years later, in 1862. Membership in the OWS cemented his status as a leading watercolourist, and he exhibited regularly at the society's exhibitions for the rest of his career, showing hundreds of works. He also exhibited occasionally at the Royal Academy in London.

Artistic Style and Idyllic Themes

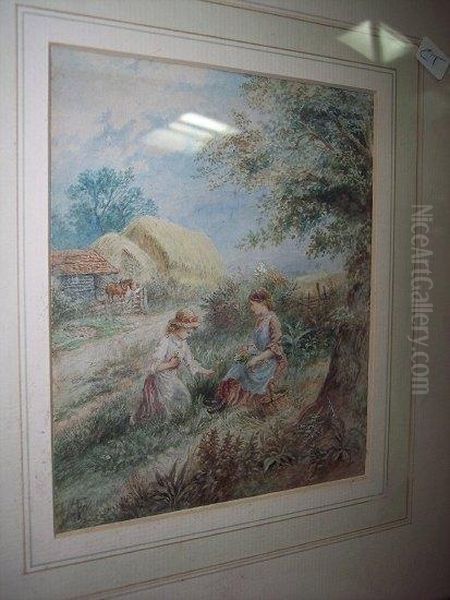

Myles Birket Foster's mature style is synonymous with the picturesque and often idealized depiction of the English countryside. His subject matter predominantly featured charming rural landscapes, quaint thatched cottages adorned with climbing roses, rustic bridges over gentle streams, leafy lanes, and scenes of pastoral life. Children feature prominently in his work, often shown playing, gathering flowers, tending geese, or helping with simple farm tasks, embodying innocence and rural contentment.

His approach was rooted in detailed naturalism. He possessed a keen eye for observation, meticulously rendering the textures of stone and wood, the delicate forms of wildflowers, the play of sunlight through leaves, and the specific character of different trees and landscapes. This attention to detail likely stemmed from his training as an illustrator and resonated with the aesthetic principles championed by the influential critic John Ruskin, who advocated for "truth to nature." Foster's Sunset study with a mackerel sky is noted for its Ruskinian attention to atmospheric detail.

However, Foster's naturalism was tempered by a distinct tendency towards idealization. His paintings rarely depict the harsh realities of 19th-century rural poverty or agricultural labour. Instead, they present a sanitized, harmonious vision of country life – a peaceful, sunlit world untouched by the rapid industrialization and urbanization transforming Victorian Britain. His figures appear happy and content, living in harmony with their picturesque surroundings, as seen in works like Bringing in the Calf.

This romanticized portrayal struck a chord with the Victorian public, many of whom lived in increasingly crowded cities and felt a nostalgic longing for a simpler, pre-industrial past. Foster's work offered an escape, a vision of England as a timeless rural paradise. While some later critics, and even some contemporaries, found his work overly sentimental or repetitive, its immense popularity during his lifetime is undeniable. His style contrasted sharply with the gritty realism being explored by artists like Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet in France.

Foster drew inspiration from his extensive travels throughout Britain, including Surrey, Sussex, Cornwall (Along the Cornish Coast), Scotland, and Wales, as well as trips to the Continent, particularly France and Germany. The landscapes and villages he encountered provided endless subject matter, though he often composed scenes by combining elements observed in different locations to create a perfect picturesque arrangement.

Life in Witley and the Artistic Community

In 1863, Foster commissioned the building of a substantial house, "The Hill," in Witley, a picturesque village near Godalming in Surrey. Designed in the Tudor style by the architect J. W. Penfold, with interior decorations contributed by leading artists and designers like William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones of the Pre-Raphaelite circle, the house became a significant hub for artists and writers.

Foster and his second wife, Frances (née Watson, whom he married after the death of his first wife, Anne Spence, in 1859), were known for their hospitality. "The Hill" attracted numerous visitors from the London art world, including painters like Frederick Walker, George Pinwell (fellow illustrators sometimes grouped with Foster as part of the "Idyllic School"), and possibly members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, although direct collaboration seems limited. The presence of Foster and other artists helped turn the Witley area into something of an artists' colony.

His life in Witley provided him with direct access to the Surrey landscapes that feature so prominently in his work. The rolling hills, woodlands, and charming villages of the region became his signature subject matter. His success allowed him to live comfortably, surrounded by the beauty he depicted in his art. He also amassed a significant personal art collection at "The Hill."

An interesting anecdote relates to a misunderstanding in 1861 when Foster mistakenly believed his father had passed away, highlighting the personal dramas that occurred alongside his professional success. His relationship with his second wife, Frances, was reportedly close, and she played a role in preserving his legacy, potentially helping to compile collections of his work after his death.

Later Years, Legacy, and Collections

Myles Birket Foster remained exceptionally productive throughout his later career, continuing to paint and exhibit his popular watercolours. His work was widely reproduced, not only through engravings in books and magazines but also appearing on decorative items, most famously on Cadbury's chocolate boxes starting in the 1860s, which further broadened his public recognition.

However, by the early 1890s, Foster began to suffer from declining health. In 1893, illness forced him to sell "The Hill" and disperse much of his valuable art collection. He moved to Weybridge, Surrey, seeking a less demanding environment.

Myles Birket Foster passed away in Weybridge on March 27, 1899, at the age of 74. He was buried in the churchyard of All Saints' Church in Witley, the village he had called home for three decades and immortalized in countless paintings. He left behind a vast body of work, including potentially unfinished pieces.

Foster's legacy is multifaceted. As an illustrator, he was a key figure in the "Golden Age" of British illustration during the mid-19th century, influencing contemporaries like Frederick Walker and George Pinwell. As a watercolourist, he achieved immense popular acclaim and commercial success, becoming one of the best-known artists of his generation. His distinctive stippling technique and his idealized vision of rural England made his work instantly recognizable.

While his reputation experienced a decline in the early 20th century with the rise of Modernism, which often dismissed Victorian sentimentality, there has been a renewed appreciation for his technical skill, his contribution to watercolour painting, and his role as a chronicler of a particular Victorian sensibility. His works remain highly sought after by collectors.

Today, Myles Birket Foster's paintings, drawings, and illustrations can be found in numerous public and private collections around the world. Major UK institutions holding his work include the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) and Tate Britain in London. In the United States, examples can be found at the Yale Center for British Art, the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University, and Bryn Mawr College Collections, among others. His enduring popularity confirms his status as a significant and much-loved figure in British art history.