Introduction: An Overview of the Artist

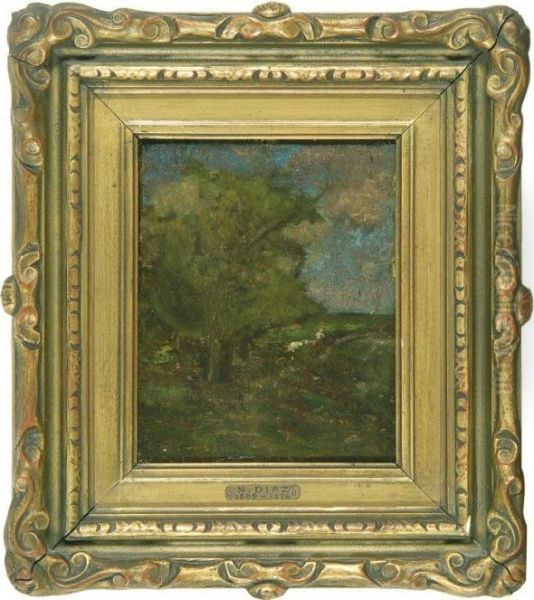

Narcisse-Virgile Diaz de la Peña stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 19th-century French art. Born in 1807 and passing away in 1876, his life spanned a period of immense artistic change and innovation. Primarily celebrated as a landscape painter, Diaz was a pivotal member of the Barbizon School, a movement that revolutionized the way artists perceived and depicted nature. Though his parents were Spanish immigrants, Diaz became intrinsically linked to the French artistic tradition, particularly through his evocative portrayals of the Forest of Fontainebleau. His work is characterized by a romantic sensibility, a masterful handling of light and shadow, and a rich, often jewel-like application of color, distinguishing him even within the talented cohort of the Barbizon painters.

Diaz's journey into the art world was unconventional, marked by early hardship and a physical disability that might have deterred others. Yet, he forged a successful career, gaining recognition at the prestigious Paris Salon and earning the respect of his contemporaries and patrons. His influence extended beyond his immediate circle, touching upon the nascent Impressionist movement. Understanding Diaz requires exploring his unique background, his artistic evolution, his contributions to the Barbizon School, his signature style, his key works, and his lasting legacy within the broader narrative of art history. He was an artist who bridged Romanticism with a burgeoning naturalism, leaving behind a body of work admired for both its technical brilliance and its poetic depth.

Early Life and Formative Years

Narcisse-Virgile Diaz de la Peña was born in Bordeaux, France, on August 20, 1807. His parents, Tomás Diaz and Maria Manuela Belasco, were Spanish political refugees who had fled the Iberian Peninsula during the Napoleonic Wars. This Spanish heritage would subtly inform aspects of his artistic sensibility, perhaps contributing to the richness of his palette and his inclination towards dramatic themes. Tragedy struck early in Diaz's life; he was orphaned by the age of ten. Following the loss of his parents, he found refuge under the care of a Protestant pastor in Bellevue, near Meudon, just outside Paris.

A defining incident occurred during his childhood, around the age of twelve or thirteen. While wandering in the woods near Sèvres, Diaz suffered a severe bite from a viper or adder. The resulting infection was grave, ultimately necessitating the amputation of his left leg. This physical challenge profoundly impacted his life but did not extinguish his spirit or his burgeoning interest in art. Equipped with a wooden prosthetic leg, he navigated the world with resilience. This early encounter with the untamed, potentially dangerous side of nature might also be seen as a formative experience, perhaps influencing his later fascination with the wild, mysterious interiors of the forest.

His initial foray into the arts was practical rather than academic. To support himself, Diaz began working as a porcelain painter, first in Paris and later finding employment at the renowned Sèvres manufactory. This craft-based training proved invaluable. Working with glazes and firing techniques likely honed his sensitivity to color saturation, luminosity, and the decorative potential of surfaces. It was during this period, decorating porcelain with intricate designs, that he began to cultivate the technical skills and aesthetic preferences that would later define his oil paintings. This practical foundation set him apart from many artists who followed a purely academic path.

Transition to Painting and Early Influences

While working with porcelain provided a livelihood and technical grounding, Diaz's ambitions soon turned towards fine art painting. He sought formal instruction, studying briefly with the academic painter Alexandre Cabanel's teacher, François Souchon, though Diaz's temperament seemed ill-suited to rigid academic methods. He was largely self-taught, absorbing lessons from the masters he admired by studying their works directly, particularly in the Louvre Museum. His early artistic development reveals a fascination with the colorists and romantics who preceded him.

One of the most significant early influences was the great French Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix. Diaz deeply admired Delacroix's vibrant palette, dramatic compositions, and exploration of exotic, often Orientalist themes. The energy, passion, and rich color harmonies found in Delacroix's work resonated with Diaz's own burgeoning romantic inclinations. This influence is visible in Diaz's early figure paintings, which often featured mythological subjects, odalisques, or scenes inspired by Middle Eastern or Turkish motifs, echoing the Orientalist trend popular in the era.

Another key figure shaping Diaz's early style was Pierre-Paul Prud'hon. Diaz was particularly captivated by Prud'hon's soft, sfumato technique and his sensual, often allegorical or mythological, figure compositions, such as Sleeping Nymph and Artemis Disarming Apollo. Prud'hon's delicate handling of light and shadow, creating a dreamy, poetic atmosphere, offered a counterpoint to Delacroix's more fiery drama and appealed to Diaz's lyrical side. Furthermore, Diaz looked back to the High Renaissance, particularly admiring the work of the Italian master Correggio, known for his graceful figures and masterful chiaroscuro. The sensuousness and soft modeling found in Correggio's paintings left an imprint on Diaz's approach to depicting the human form in his earlier works.

The legacy of 18th-century French Rococo painting also played a role. Artists like Jean-Antoine Watteau, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, and Jean-Baptiste Greuze, known for their fêtes galantes (elegant outdoor parties), decorative charm, and sometimes sentimental themes, provided a precedent for Diaz's own depictions of figures, often nymphs or elegantly dressed women, situated within idyllic landscape settings. This blend of Romantic color, Prud'hon's softness, Correggio's grace, and Rococo charm, combined with an emerging interest in landscape, formed the complex foundation upon which Diaz would build his mature style.

The Barbizon School and the Call of Nature

Around the 1830s, Diaz's artistic focus began to shift decisively towards landscape painting. This coincided with the rise of the Barbizon School, a loose collective of artists who gathered near the village of Barbizon, on the edge of the vast Forest of Fontainebleau, south of Paris. Rejecting the idealized, historical landscapes favored by the Neoclassical tradition, the Barbizon painters sought a more direct, truthful, and personal engagement with nature. They championed painting en plein air (outdoors), at least in sketching, to capture the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere.

Diaz was drawn to this movement and its locus, the Forest of Fontainebleau. He began exhibiting landscapes at the Paris Salon in 1831. A pivotal moment came around 1836-1837 when he encountered Théodore Rousseau, who would become one of the leading figures of the Barbizon School. Diaz deeply admired Rousseau's profound understanding of nature, his meticulous observation, and his ability to convey the structure and character of trees and terrain. He actively sought Rousseau's guidance, and despite Rousseau's initially reserved nature, a friendship and mentorship developed. Rousseau instructed Diaz in techniques for rendering the natural world with greater fidelity, sharing his knowledge gleaned from studying 17th-century Dutch landscape masters like Jacob van Ruisdael and Meindert Hobbema.

Diaz quickly became a central figure within the Barbizon group. While sharing the group's commitment to naturalism and direct observation, his interpretation remained distinctly personal. Unlike the often somber or rustic realism of Jean-François Millet, who focused on peasant life, or the tranquil, silvery light of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot's later work, Diaz brought a more overtly romantic and decorative sensibility to his forest scenes. He was particularly fascinated by the dense, shadowy interiors of the forest, the play of sunlight filtering through thick canopies, and the rich textures of bark, moss, and undergrowth.

Other important artists associated with the Barbizon movement, alongside Diaz, Rousseau, Millet, and Corot, included Charles-François Daubigny, known for his river scenes often painted from his studio boat; Jules Dupré, whose work often featured dramatic skies and turbulent landscapes; and Constant Troyon, initially a landscape painter who later specialized in animal painting. Diaz interacted with these artists, sharing ideas and sketching expeditions in Fontainebleau. He fully embraced the Barbizon ethos of finding beauty and meaning in the unadulterated French landscape, particularly the ancient, varied terrain of the forest.

Artistic Style: Romanticism, Color, and Light

Diaz de la Peña's mature style is a unique synthesis of Barbizon naturalism and his inherent Romantic inclinations. While he learned from Rousseau to observe nature closely, he rarely aimed for topographical accuracy in the way some of his colleagues did. Instead, he used the forest as a stage for exploring dramatic effects of light and color, often imbuing his scenes with a sense of mystery, enchantment, or impending drama.

Color was paramount for Diaz. He employed a rich, often dark palette, punctuated by brilliant highlights. His greens are deep and resonant, his browns earthy and textured. What truly set him apart was his use of jewel-like accents – touches of vibrant red, blue, or yellow, often representing wildflowers, figures' clothing, or shafts of sunlight hitting the forest floor. This technique lent his canvases a sparkling, almost incandescent quality. He was known for his love of thick paint application, or impasto, using textured brushwork to convey the roughness of bark, the density of foliage, or the sparkle of light on wet surfaces. He explicitly stated his preference for color and paint texture over the precise linearity favored by academic tradition.

Light and shadow were his primary tools for creating mood and drama. He excelled at depicting clair-obscur (chiaroscuro) effects within the forest interior. Sunlight doesn't just illuminate; it pierces the gloom, dapples the ground, and creates strong contrasts that heighten the emotional impact of the scene. His forest clearings often feel like secret worlds, bathed in an almost magical light, while his depictions of storms capture the dynamic energy and atmospheric turmoil of nature unleashed.

While celebrated for his landscapes, Diaz frequently incorporated figures into his scenes. These were often small, serving to provide scale or a focal point of color, but sometimes they were central to the theme. Nymphs, mythological figures (like Diana the huntress), elegantly dressed ladies reminiscent of Rococo paintings, or groups of "Bohemians" (often interpreted as Romani people or exotic figures) populate his woodland settings. This blending of landscape with figure painting, often carrying mythological or romantic connotations, connects back to his early influences and distinguishes his work from the purer landscape focus of artists like Rousseau or Daubigny. His style remained remarkably consistent, characterized by this romantic vision, rich color, and dramatic interplay of light and dark.

Representative Works

Diaz de la Peña was a prolific artist, and several works stand out as representative of his style and achievements.

Descent of the Bohemians (1844): Exhibited at the Salon of 1844, this painting was a major success, solidifying Diaz's reputation. It depicts a colorful group, often identified as Romani people, making their way through a sun-dappled forest clearing. The work combines his skill in landscape – the detailed rendering of trees and foliage, the dramatic lighting – with his interest in exotic figure groups. The vibrant costumes of the figures provide splashes of bright color against the deeper tones of the forest, showcasing his characteristic palette and his ability to integrate narrative elements within a natural setting. This work captured the public imagination and earned him critical acclaim.

The Approaching Storm (c. 1850s-1860s): Diaz painted numerous storm scenes, and this theme allowed him to fully explore dramatic light effects and atmospheric turbulence. Works titled The Approaching Storm or similar typically depict a dark, brooding sky lowering over a wind-swept forest landscape. Trees bend under the force of the wind, and a dramatic contrast exists between the shadowed foreground and patches of intense, almost eerie light breaking through the clouds. He often employed a wet-on-wet technique in these works to achieve fluid transitions and capture the sense of moisture in the air. These paintings exemplify the sublime power of nature, a key theme in Romanticism.

Forest of Fontainebleau (Various dates): Diaz returned repeatedly to the Forest of Fontainebleau, capturing its varied moods and locations. Many works simply bear titles like Forest Interior, Clearing in the Forest, or Pool in the Forest. These paintings are perhaps the most characteristic of his oeuvre. They often feature towering oak or birch trees, moss-covered rocks, dense undergrowth, and a signature play of light filtering through the leaves. Small figures might be present, or the landscape itself might be the sole subject. He masterfully conveyed the textures of the forest – rough bark, damp earth, shimmering leaves – through his rich impasto and vibrant color. These works cemented his association with the Barbizon School and the forest itself.

Flowers in a Woodland Glade (Various dates): Reflecting his background in porcelain painting and his decorative sense, Diaz often painted detailed studies of wildflowers nestled in the forest floor or arranged in woodland settings. These works highlight his sensitivity to color and texture on a smaller scale. The bright hues of the flowers – reds, yellows, blues – sparkle like jewels against the darker backdrop of earth and leaves, demonstrating his ability to find beauty in intimate details as well as grand vistas.

Diana and Cupid / Mythological Scenes (Various dates): Throughout his career, Diaz continued to paint mythological and allegorical subjects, often placing figures like Venus, Cupid, or Diana and her nymphs within lush forest landscapes. These works connect to his early influences (Prud'hon, Correggio) and the Rococo tradition. While the landscapes retain his Barbizon style, the figures are often rendered with a softer, more idealized touch. These paintings showcase his versatility and his enduring interest in classical and romantic themes alongside pure landscape.

These examples illustrate the core elements of Diaz's art: his mastery of forest scenery, his dramatic use of light and color, his blend of naturalism and romanticism, and his occasional integration of figures and narrative elements. His works consistently convey a deep appreciation for the beauty, mystery, and sometimes untamed power of the natural world.

Connections, Contemporaries, and Influence

Diaz de la Peña was well-connected within the Parisian art world of his time. His closest artistic relationship was undoubtedly with Théodore Rousseau. Their friendship, though sometimes tested by Rousseau's difficult personality, was mutually beneficial. Diaz gained invaluable technical knowledge from Rousseau, while Diaz's commercial success and more sociable nature perhaps helped promote the Barbizon ideals to a wider audience. They often sketched together in Fontainebleau, sharing a deep love for the forest.

He was a core member of the Barbizon group, working alongside Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Jean-François Millet, Charles-François Daubigny, and Jules Dupré. While each had a distinct style, they shared a commitment to landscape and influenced one another through proximity and shared exhibitions. Diaz's work, with its richer color and more romantic flair, offered a different perspective within the group's overall naturalist aims.

Diaz also knew Gustave Courbet, the leading figure of the Realist movement. While their artistic philosophies differed – Courbet's realism was more politically charged and focused on unvarnished reality, whereas Diaz retained a romantic sensibility – they shared an interest in landscape and likely encountered each other in artistic circles. Diaz's focus remained more on the poetic and atmospheric aspects of nature rather than the social commentary often present in Courbet's work.

Perhaps one of Diaz's most significant legacies lies in his influence on the next generation, particularly the Impressionists. The young Pierre-Auguste Renoir deeply admired Diaz's work, especially his handling of color and light, and his depictions of figures in sun-dappled landscapes. Renoir reportedly sought out Diaz in the Forest of Fontainebleau around 1862, receiving encouragement and perhaps informal advice. Diaz's rich palette, broken brushwork (in his highlights), and interest in capturing fleeting light effects can be seen as precursors to Impressionist techniques. Renoir's later works, with their luminous color and dappled sunlight, owe a debt to Diaz's example. Other Impressionists, like Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, while developing their own revolutionary styles, were certainly aware of Diaz and the Barbizon painters, whose liberation of landscape from academic constraints paved the way for their own experiments. Diaz's emphasis on color and light, even within a more traditional framework, resonated with the Impressionists' core concerns.

Recognition, Later Years, and Legacy

Narcisse Diaz de la Peña achieved considerable success during his lifetime. After his initial Salon entries in the 1830s, his reputation grew steadily. He won several awards at the Salon, including third-class medals in 1844 and 1846, a second-class medal in 1847, and a first-class medal in 1848. This official recognition culminated in 1851 when he was made a Knight of the Legion of Honour, a prestigious acknowledgment of his contribution to French art.

His paintings became highly sought after by collectors, particularly during the Second Empire and early Third Republic. His forest scenes, with their rich color and romantic atmosphere, appealed to the tastes of the burgeoning bourgeoisie. He maintained a studio in Paris, which became a gathering place for fellow artists, writers, and patrons, cementing his position within the cultural life of the city. He was known for his generosity towards younger or struggling artists, including, reportedly, Renoir.

During the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) and the subsequent Paris Commune, Diaz temporarily relocated to Brussels, returning to France afterwards. He continued to paint actively, though his later works sometimes show a looser handling, perhaps reflecting the influence of the emerging Impressionist aesthetic he had helped to inspire.

Diaz de la Peña passed away in Menton, on the French Riviera, on November 18, 1876. The cause of death was reportedly related to a cold contracted while visiting the tomb of his son, Emile, who had died in 1867. Another son, Eugène-Émile (also an artist), sadly died in the same year as his father.

His legacy is substantial. As a key member of the Barbizon School, he played a vital role in shifting the focus of French landscape painting towards a more direct, personal, and naturalistic approach, breaking free from Neoclassical conventions. His unique style, blending romanticism, rich color, and dramatic light, offered a distinct voice within the movement. His work influenced subsequent generations, most notably providing a bridge towards Impressionism through his emphasis on color, light effects, and visible brushwork, particularly admired by Renoir.

Today, Diaz de la Peña's paintings are held in major museum collections worldwide, including the Louvre Museum in Paris, the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery in London, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Art Institute of Chicago, and many others. His works continue to be appreciated for their technical skill, their evocative beauty, and their important place in the evolution of 19th-century landscape painting. Auction results, like the $16,000 sale of a Landscape in 2003 mentioned in the source material, confirm the enduring market interest and historical value placed on his art.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Narcisse-Virgile Diaz de la Peña remains an essential figure for understanding the transition in French art during the mid-19th century. Overcoming personal hardship, he forged a unique artistic identity, becoming a leading light of the Barbizon School. His paintings of the Forest of Fontainebleau are not mere transcriptions of nature but poetic interpretations, imbued with romantic feeling and rendered with a masterful command of color and light. He successfully synthesized the Barbizon dedication to observed reality with his own innate sense for drama and decoration, influenced by predecessors like Delacroix and Prud'hon, and even the Rococo masters.

His contribution extends beyond his own beautiful canvases. By championing landscape painting grounded in direct experience and emphasizing the expressive potential of color and light, he helped pave the way for the Impressionist revolution. His mentorship, however informal, of figures like Renoir underscores his role as a transitional artist. Diaz's ability to capture the mysterious allure of the forest interior, the sparkle of sunlight on foliage, and the drama of changing weather ensures his work continues to resonate with viewers. He stands as a testament to the power of resilience and the enduring appeal of a romantic vision fused with a deep love for the natural world.