Introduction: An Artist of Note

Nathaniel Hone the Elder (1718-1784) stands as a significant, albeit sometimes contentious, figure in the landscape of 18th-century British and Irish art. Born in Dublin, he carved out a successful career primarily in London, becoming renowned for his skillful portraits, exquisite miniatures, and occasionally sharp satirical works. As one of the founding members of the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts, his place in the establishment seemed secure, yet his independent spirit and willingness to court controversy, most notably through his infamous painting The Conjuror, ensured a more complex legacy. Hone's life and work offer a fascinating window into the bustling, competitive, and rapidly evolving art world of Georgian London.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Nathaniel Hone entered the world on April 24, 1718, in Dublin, Ireland. He was the third son in a merchant family, suggesting a background outside the established artistic dynasties of the time. Details of his earliest artistic training remain somewhat obscure; while he may have received some initial instruction, it is widely believed that Hone was largely self-taught. He honed his skills through dedicated practice and observation, developing a proficiency that would soon carry him beyond Ireland's shores.

Like many ambitious Irish artists of his generation, Hone sought greater opportunities in England. He initially travelled the country, likely working as an itinerant painter, creating portraits and miniatures for clients in various towns. This period of travel would have exposed him to different regional tastes and potentially diverse artistic influences, further shaping his practical skills. His early reputation was built significantly on his talent for miniature painting, a highly valued art form demanding precision and delicacy.

A pivotal moment came in 1742 when Hone married Mary Earle in York. Described as a woman of some property, her independent means likely provided Hone with the financial stability needed to cease his itinerant lifestyle and establish a permanent base. The couple eventually settled in London, the vibrant epicentre of the British art world, where Hone's career would truly flourish. They would go on to have a large family, with ten children, including sons who would follow artistic paths.

Ascendancy in London: Portraitist and Miniaturist

Once established in London, Nathaniel Hone quickly made a name for himself. His initial renown came from his exceptional work in miniature painting, often executed on ivory or as enamels. Enamel painting, in particular, was a demanding technique requiring meticulous skill in firing pigments onto metal or porcelain supports, and Hone excelled at it. These small-scale works showcased his remarkable ability to capture fine detail and likeness, appealing to a clientele eager for intimate keepsakes and portable portraits. His skill placed him among the leading miniaturists of the day.

Hone did not confine himself to small formats, however. He successfully transitioned to larger-scale oil portraiture, becoming a sought-after artist in this competitive field. His portraits were noted for their strong characterization and often direct, unpretentious style. Works like his Portrait of Anne Anderson (1760) demonstrate his ability to render likeness and personality effectively. He painted prominent figures, including the aristocracy, such as his portrait of Jane Roberts, Duchess of St Albans, where his attention to the sitter's features and the details of her attire and jewellery is evident.

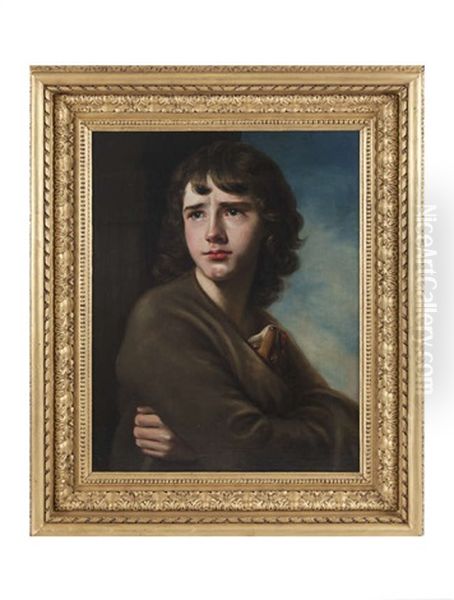

Beyond oil and miniature, Hone was also adept at working in pastels, a medium favoured for its soft textures and luminous colour. His pastel work The Spartan Boy, first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1775, was a significant piece that garnered considerable attention and further cemented his reputation within the London art scene. It demonstrated his versatility across different media and subject types, moving beyond straightforward portraiture into more narrative or allegorical themes.

The Royal Academy: Founder and Rebel

The establishment of the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1768 was a landmark event, intended to raise the status of art and artists in Britain. Nathaniel Hone was among the thirty-four founding members, a testament to the professional standing he had achieved. This initial group included the leading lights of the London art world, such as the Academy's first President, Sir Joshua Reynolds, the landscape and portrait painter Thomas Gainsborough, the American-born historical painter Benjamin West, and the notable female artists Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser. Other founders included landscape artists like Paul Sandby and George Barret Sr., and the Italian decorative painter Francesco Zuccarelli.

In the early years of the Academy, Hone participated actively, exhibiting his works regularly at its annual exhibitions. Membership offered prestige, exhibition opportunities, and a forum for artistic debate. However, Hone's relationship with the institution, and particularly with its powerful president, Reynolds, would soon become strained, culminating in one of the most famous artistic disputes of the era.

The 'Conjuror' Controversy of 1775

The year 1775 marked a dramatic turning point in Hone's relationship with the Royal Academy. He submitted a large, complex painting titled The Conjuror (or The Pictorial Conjuror, displaying the whole Art of Optical Deception) for the annual exhibition. The work was an audacious satire, widely interpreted as a direct attack on Sir Joshua Reynolds and his artistic practices. Reynolds was depicted as an aged "conjuror," using prints of Old Master paintings to magically generate his own compositions, a clear jibe at Reynolds's known habit of borrowing poses and motifs from historical art, which Hone viewed as plagiarism rather than laudable imitation.

The painting contained further inflammatory elements. Initially, it included a group of nude figures in the background, one of which was alleged to represent Angelica Kauffman, another prominent RA founder. At the time, rumours circulated about a close relationship between Reynolds and Kauffman, and Hone's inclusion of her nude figure was seen as a scandalous and personal attack, possibly fuelled by professional jealousy or disagreement over artistic principles. Kauffman, upon learning of the painting's content, protested vehemently to the Academy Council.

The Council, finding the painting offensive and potentially libellous, demanded that Hone alter the offending parts. While Hone eventually agreed to paint over the nude figure identified as Kauffman, replacing it with other figures, he refused to make changes to the central satirical depiction of Reynolds. Consequently, the Academy rejected the painting outright, barring it from the exhibition. This public clash between a founding member and the Academy's leadership caused a significant stir in London's art circles.

A Pioneering Solo Exhibition

Rebuffed by the institution he had helped to found, Nathaniel Hone took an unprecedented step. In a bold act of defiance and self-promotion, he rented a room opposite the Royal Academy's premises in St Martin's Lane and mounted his own independent exhibition. This show, centred around the controversial Conjuror, featured around sixty other works spanning his career, showcasing his versatility in portraits, miniatures, and other subjects. He even published a catalogue with an apologia, defending his artistic integrity and explaining his side of the dispute.

This event is widely regarded as the first significant one-man retrospective exhibition staged by a living artist in Britain. It was a radical move, challenging the Royal Academy's monopoly on major public art exhibitions and asserting the artist's right to present their work directly to the public on their own terms. While perhaps born of frustration, Hone's solo show set a precedent for artistic independence that would resonate through art history, foreshadowing later challenges to academic authority by artists seeking alternative venues.

Artistic Style and Techniques Explored

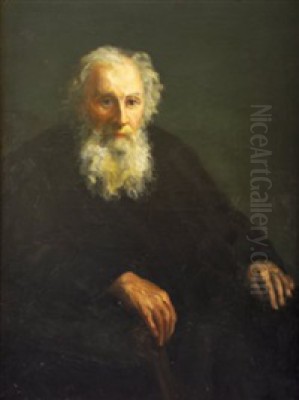

Nathaniel Hone's artistic output is characterized by solid craftsmanship and versatility. His portraiture, while perhaps lacking the fashionable elegance of Gainsborough or the grand manner of Reynolds, often possesses a directness and psychological insight. He captured likenesses effectively, paying close attention to facial features and expressions, particularly evident in his sensitive portrayals of children. His approach can be compared to other leading portraitists of the time like Allan Ramsay or George Romney, each offering a distinct flavour within the flourishing market for portraiture.

His mastery of miniature painting remained a constant throughout his career. These small works, whether on ivory or enamel, demonstrate his meticulous attention to detail and skillful handling of colour. His technique in enamels was particularly admired. This focus on detailed realism and rich surfaces shows an affinity with the traditions of earlier European art, including the Dutch Golden Age masters like Rembrandt, whose work was increasingly collected and appreciated in 18th-century Britain.

Hone was also proficient in pastel, as seen in The Spartan Boy, achieving soft yet defined forms and subtle colour gradations. His satirical impulse, most famously unleashed in The Conjuror, connects him to a strong British tradition of graphic satire, exemplified by the earlier work of William Hogarth. While The Conjuror is his most notorious satirical piece, other works like Two Disguised Gentlemen suggest a recurring interest in humour and social observation. He also painted genre scenes or "fancy pictures," such as The Shepherdess, broadening his thematic range.

Key Works Revisited

Several works stand out in Nathaniel Hone's oeuvre, illustrating his diverse talents and historical significance.

The Conjuror (1775) remains his most famous work due to the controversy it ignited. Now housed in the National Gallery of Ireland, it serves as a potent symbol of artistic rivalry and the clash between academic ideals and individual expression in the 18th century. Its satirical bite and complex iconography continue to fascinate art historians.

The Spartan Boy (exhibited 1775) highlights Hone's skill in pastel and his ability to tackle subjects beyond portraiture. Its exhibition at the Royal Academy the same year as The Conjuror's rejection underscores the complexity of his relationship with the institution – he could produce works that met with approval even amidst conflict.

Portraits like that of Jane Roberts, Duchess of St Albans exemplify his capabilities as an oil painter catering to aristocratic clientele, showcasing his attention to detail in rendering fabrics and jewels alongside the sitter's likeness.

Miniatures such as Piping Boy represent the foundation of his early success, demonstrating the exquisite craftsmanship that first brought him recognition in London's competitive art market.

Two Disguised Gentlemen offers a glimpse into Hone's lighter, perhaps more humorous side, possibly engaging in gentle social satire or simply capturing a moment of playful masquerade.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

Hone operated within a vibrant and competitive London art world populated by numerous talented individuals. His rivalry with Sir Joshua Reynolds was clearly profound, likely stemming from differing artistic philosophies as much as personal animosity. Reynolds championed the "Grand Manner," advocating the study and adaptation of Old Masters, while Hone seemed to favour a more direct, perhaps less idealized approach, viewing Reynolds's methods as derivative.

His relationship with Angelica Kauffman was complicated by the Conjuror incident. Whether motivated by professional jealousy, genuine disapproval of her perceived closeness to Reynolds, or the prevailing gender biases of the era that often questioned the seriousness of female artists, Hone's actions placed him in direct conflict with one of the most successful women artists of the time.

He worked alongside other Royal Academy founders, including the landscape painters George Barret Sr. (another Irish artist who found success in London) and Paul Sandby, and portraitists like Francis Cotes, who was also known for his fine pastel work. He would have been aware of the work of other prominent Irish artists active in London, such as the ambitious history painter James Barry, who also had a notoriously fractious relationship with the Royal Academy. The broader context includes the elegant portraiture of Thomas Gainsborough and the fashionable work of George Romney, creating a diverse artistic milieu against which Hone's more robust style can be measured.

Family, Later Life, and Legacy

Despite the upheaval of 1775, Nathaniel Hone continued to paint and occasionally exhibit. His marriage to Mary Earle endured, and they raised a large family. Artistic talent ran in the family; his son Horace Hone (c. 1754-1825) became a highly successful miniaturist in his own right. Horace studied at the Royal Academy schools, became an Associate of the RA, and was appointed Miniature Painter to the Prince of Wales (later King George IV). He later settled in Dublin, becoming a leading figure in the Irish art scene. Another son, John Camillus Hone (1759–1836), also pursued a career as a painter.

Nathaniel Hone the Elder died in London on August 14, 1784, at the age of 66. He was buried in Hendon, Middlesex. His legacy is multifaceted. He was undoubtedly a highly skilled and successful portraitist and miniaturist, whose works are preserved in major collections like the National Gallery, London, and the National Gallery of Ireland. He was a foundational figure of the Royal Academy, yet also one of its earliest and most public rebels.

His pioneering solo exhibition remains a significant event in the history of art display and marketing. He stands as an important figure in the history of Irish art, one of the many talented individuals who sought and found success in the larger artistic centre of London, while retaining connections to his homeland, partly through his artist sons.

Market Presence and Enduring Interest

Works by Nathaniel Hone the Elder continue to appear on the art market, indicating sustained interest from collectors. Auction records show a range of prices depending on the medium, size, subject, and condition of the work. Portraits in oil command significant sums, with estimates and sale prices reaching tens of thousands of pounds or euros for well-preserved examples of notable sitters. Miniatures and enamels also remain sought after by specialists. Even associated items, like clothing depicted in his portraits, have appeared at auction, highlighting the historical interest surrounding his work and sitters. This market activity confirms his established place within the canon of 18th-century British and Irish painters.

Conclusion: A Complex Contribution

Nathaniel Hone the Elder was more than just a competent face-painter. He was a master craftsman in multiple media, a founding father of Britain's most important art institution, and a figure unafraid to challenge its authority. His career reflects the opportunities and pressures faced by artists in Georgian London. While the Conjuror incident often dominates discussions of his life, it should not overshadow his considerable achievements as a portraitist and miniaturist. His blend of technical skill, artistic independence, and occasional contentiousness makes him an enduringly fascinating figure, representing both the successes and the struggles inherent in navigating the complex art world of his time. His work provides valuable insights into 18th-century society, patronage, and the evolving role of the artist.