Nicolai Abraham Abildgaard, a towering figure in Danish art history, stands as a pivotal artist who masterfully navigated the transition from the structured ideals of Neoclassicism to the burgeoning emotionalism of Romanticism. Born on September 11, 1743, in Copenhagen, and passing away on June 4, 1809, at his estate Frederiksdal, near the city, Abildgaard's life and career were marked by profound intellectual curiosity, artistic innovation, and a significant role in shaping the course of Scandinavian art. His multifaceted talents extended beyond painting to encompass sculpture, architecture, design, and influential academic leadership.

Early Life and Formative Education

Born into an environment steeped in intellectual and artistic pursuits, Nicolai Abraham Abildgaard was the son of Søren Abildgaard, a respected naturalist, writer, and antiquarian draughtsman, and Anne Margrethe Bastholm. This upbringing undoubtedly fostered his inquisitive mind and appreciation for both the arts and sciences. His formal artistic training commenced at the prestigious Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts (Det Kongelige Danske Kunstakademi) in Copenhagen, an institution that would later become central to his own career.

At the Academy, he studied under figures who were themselves bringing new European artistic currents to Denmark. Key among his instructors were Johan Edvard Mandelberg and the sculptor Johannes Wiedewelt. Both Mandelberg, a history painter, and Wiedewelt had spent considerable time in Paris and Rome, absorbing the principles of Neoclassicism championed by theorists like Johann Joachim Winckelmann and artists such as Anton Raphael Mengs. They instilled in Abildgaard a reverence for classical antiquity and the grand tradition of history painting.

Abildgaard proved to be a prodigious student. He distinguished himself early on, winning the Academy's small silver medal in 1764, followed by the large silver medal in 1765, the small gold medal in 1766 for Joash, King of Judah, Saved from Athaliah's Cruelty, and finally, the coveted large gold medal in 1767 for The Stoning of Stephen. This ultimate prize came with a travel stipend, enabling him to embark on the traditional artistic pilgrimage to Rome, the epicenter of classical art and a crucial destination for any aspiring history painter of the era.

The Transformative Roman Sojourn (1772-1777)

Abildgaard's arrival in Rome in 1772 marked a profoundly influential period in his development. He immersed himself in the study of ancient Roman art and architecture, as well as the masterpieces of the High Renaissance, particularly the works of Raphael, Michelangelo, and Titian. He was also captivated by the powerful compositions and dramatic intensity of Baroque artists like Annibale Carracci, whose Farnese Gallery frescoes left a lasting impression.

During his five-year stay, Abildgaard was not isolated. He became part of a vibrant international community of artists. He formed a close friendship with the Swedish sculptor Johan Tobias Sergel, another key figure in Scandinavian Neoclassicism, and the Swiss-born British painter Johann Heinrich Füssli (Henry Fuseli). Fuseli, known for his dramatic, often unsettling, and proto-Romantic interpretations of literary and mythological themes, exerted a significant influence on Abildgaard, encouraging a more expressive and imaginative approach that sometimes veered into the sublime and the terrifying. The intellectual ferment of Rome, with ongoing archaeological discoveries at Pompeii and Herculaneum fueling the Neoclassical fervor, provided a rich backdrop for his studies. He also likely encountered the work of Giovanni Battista Piranesi, whose dramatic etchings of Roman ruins conveyed a sense of grandeur and decay that resonated with emerging Romantic sensibilities.

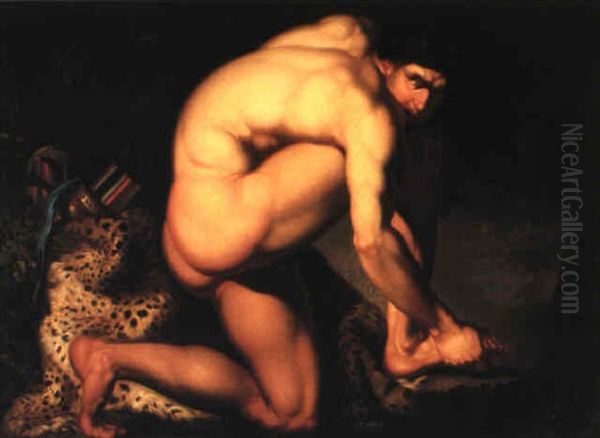

His Roman period was highly productive. He diligently copied classical sculptures and Renaissance paintings, honing his skills and deepening his understanding of form, composition, and narrative. It was here that he painted one of his early masterpieces, The Wounded Philoctetes (1775, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen). This powerful work, depicting the suffering hero from Greek mythology abandoned on the island of Lemnos, showcases his mastery of anatomical rendering, dramatic composition, and the Neoclassical emphasis on noble suffering, yet it also hints at a more intense, almost Romantic, emotionality.

Return to Denmark and Academic Ascendancy

Upon his return to Copenhagen in 1777, Abildgaard's reputation, bolstered by his Roman studies and works like Philoctetes, was already considerable. He was admitted as a member of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in 1778, presenting The Stoning of Stephen (a revised version of his gold medal piece) as his reception piece. He was soon appointed a professor at the Academy, a position he held with great dedication.

Abildgaard's role at the Academy was transformative. He was not merely a painter but a significant intellectual force. He taught not only painting but also mythology and anatomy, subjects crucial for aspiring history painters. His lectures were renowned for their erudition and his ability to inspire students. He served as the Academy's Director from 1789 to 1791 and again from 1801 until his death in 1809. During his tenures, he sought to modernize the curriculum, emphasizing a rigorous grounding in classical principles while also being open to new artistic currents.

His influence extended to a generation of Danish artists who would go on to define the Danish Golden Age of painting. Among his most notable students were Bertel Thorvaldsen, who would become one of Europe's most celebrated Neoclassical sculptors, rivaling even Antonio Canova; Asmus Jacob Carstens, a German-Danish painter who became a leading figure of Neoclassicism in Germany; and Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, often hailed as the "Father of Danish Painting" for his pivotal role in establishing a distinct national school of art. Abildgaard's guidance provided these artists with a strong foundation, even as they developed their own unique styles.

Artistic Style: Bridging Neoclassicism and Romanticism

Abildgaard's artistic style is complex, characterized by a dynamic interplay between the clarity, order, and idealized forms of Neoclassicism and the emotional intensity, individualism, and interest in the sublime and the national past that defined emerging Romanticism. His compositions are often grand and theatrical, with a strong emphasis on draughtsmanship and anatomical precision, hallmarks of his Neoclassical training.

He drew heavily on classical mythology, biblical narratives, and historical events for his subject matter. Works like Socrates and Aspasia (c. 1780) and Cupid and Psyche (c. 1790s) demonstrate his engagement with classical themes, often imbued with a sense of drama and psychological depth. His figures are typically heroic and idealized, yet they often convey powerful emotions, from stoic suffering to passionate intensity.

However, Abildgaard was also a pioneer in exploring themes from Nordic mythology and literature, a key interest of the Romantic movement. His painting Ossian Singing His Swan Song (1780-82, Statens Museum for Kunst), also known as Ossian's Last Song, is a prime example. Inspired by the epic poems of Ossian (a literary fabrication by James Macpherson that captivated Europe), the work depicts the blind bard in a wild, melancholic landscape, a subject far removed from the sunny climes of classical antiquity. This interest in national myths and a more somber, introspective mood aligns him with early Romantic artists like Fuseli and, in a broader sense, with the literary currents that would inspire painters like Caspar David Friedrich, who himself studied in Copenhagen, albeit after Abildgaard's peak.

His color palette could range from the restrained tones favored by Neoclassicists to more vibrant and dramatic hues when the subject demanded. His brushwork was generally smooth and polished, emphasizing clarity of form, but he could also employ more expressive handling to heighten emotional impact.

Major Works and Royal Commissions

Abildgaard's oeuvre is rich and varied, but several works and commissions stand out for their artistic significance and historical importance.

The Wounded Philoctetes (1775) remains one of his most iconic paintings. The depiction of the hero's agony, his muscular body contorted in pain, is a tour-de-force of anatomical study and emotional expression. It perfectly encapsulates the Neoclassical ideal of "noble simplicity and quiet grandeur" as described by Winckelmann, yet the rawness of Philoctetes' suffering pushes towards a more Romantic sensibility.

The decorations for the Knights' Hall (Riddersalen) in Christiansborg Palace, the royal residence in Copenhagen, constituted one of his most ambitious projects. Beginning in 1778, he was commissioned to create a series of large-scale history paintings depicting significant events from Danish history, from legendary sagas to more recent monarchs. These works were intended to glorify the Danish monarchy and foster a sense of national pride. Unfortunately, a catastrophic fire at Christiansborg Palace in 1794 destroyed most of these monumental paintings, a devastating loss for Danish art and for Abildgaard personally. Only sketches and a few smaller related pieces survive, such as The Cult of Odin and Queen Gunhild.

Despite this setback, Abildgaard continued to receive important commissions. He created designs for other royal palaces, including Fredensborg Palace and Levetzau's Palace at Amalienborg, where he was involved in interior decoration schemes that showcased his Neoclassical taste.

His interest in literary themes continued throughout his career. Besides Ossian, he drew inspiration from Shakespeare, as seen in works like Hamlet and his Mother (c. 1778), and from classical authors like Apuleius for his depictions of Cupid and Psyche. He also painted allegorical subjects, such as the Allegorical Figure of Theology, demonstrating his intellectual engagement with abstract concepts.

Another significant work is Cicero in Prison Pointing to his Writings (c. 1794, Statens Museum for Kunst), which reflects the Enlightenment's admiration for classical republican virtues and the power of intellect in the face of adversity. The stoic figure of Cicero, illuminated in his dark cell, embodies resilience and the enduring value of knowledge.

Architectural and Decorative Arts

Abildgaard's talents were not confined to the canvas. He was also a gifted architect and designer, deeply influenced by classical principles of proportion, harmony, and order. Although few of his architectural projects were fully realized, his designs demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of Neoclassical architectural language.

He designed his own house in Copenhagen, a testament to his aesthetic ideals. More significantly, he was involved in the design and decoration of interiors for royal and aristocratic patrons. His work at Amalienborg, particularly in Levetzau's Palace (now Christian VIII's Palace), involved creating cohesive Neoclassical schemes that integrated painting, sculpture, and decorative elements. He designed furniture, stucco work, and other ornamental details, often drawing inspiration from ancient Roman models discovered at Pompeii and Herculaneum, or from Renaissance interpretations of classical motifs.

His approach to decorative arts was holistic, aiming to create harmonious environments where every element contributed to an overall aesthetic effect. This comprehensive vision aligns him with other Neoclassical artists like Robert Adam in Britain, who also oversaw entire interior design projects.

Intellectual Pursuits and Writings

Beyond his artistic and academic roles, Abildgaard was a man of wide-ranging intellectual interests. Reflecting his father's scientific inclinations, he engaged with natural history and even wrote on subjects like fossil bones, proposing theories about Earth's history and species evolution. While these scientific views were not widely accepted at the time and were speculative by modern standards, they underscore his broad intellectual curiosity and his engagement with the Enlightenment's spirit of inquiry.

He was also a keen observer of political and social developments. His art sometimes carried subtle political undertones, reflecting the revolutionary ideas circulating in Europe during the late 18th century. Some scholars have interpreted certain works as critiques of tyranny or as expressions of republican ideals, though these interpretations are often nuanced and open to debate. His intellectualism and sometimes critical stance occasionally brought him into conflict with conservative elements of Danish society.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Abildgaard's career unfolded within a dynamic artistic landscape, and his relationships with contemporaries were multifaceted.

His teachers, Johan Edvard Mandelberg and Johannes Wiedewelt, provided his foundational Neoclassical training. In Rome, his friendships with Johan Tobias Sergel and Henry Fuseli were crucial. Sergel shared his Neoclassical grounding, while Fuseli pushed him towards more imaginative and emotionally charged territory. He would have been aware of other leading Neoclassicists active in Rome, such as Anton Raphael Mengs and Pompeo Batoni, and the influential theories of Winckelmann.

In Denmark, he was a contemporary of Jens Juel, a leading portrait painter of the era. While their primary genres differed, they were both key figures in the Danish art scene and maintained a respectful professional relationship; Juel famously painted portraits of Abildgaard.

As a professor, his most significant relationships were with his students. Bertel Thorvaldsen, perhaps his most famous pupil, absorbed Abildgaard's Neoclassical principles and carried them to international fame in sculpture. Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, another star student, built upon Abildgaard's legacy to usher in the Danish Golden Age, though Eckersberg's style would evolve towards a more precise realism. Asmus Jacob Carstens, though his career largely unfolded in Germany, also benefited from Abildgaard's tutelage.

The broader European context included figures like Jacques-Louis David in France, the preeminent Neoclassical painter whose revolutionary fervor and stark classicism represented a more politically charged form of the style. Angelica Kauffman, a Swiss-born Neoclassical painter active in Rome and London, was another prominent female artist of the period. While Abildgaard's direct interactions with all these figures varied, their work formed the artistic milieu in which he operated. His proto-Romantic leanings also connect him thematically to artists like William Blake in England, whose visionary art, though stylistically different, shared an interest in the sublime and the imaginative.

Personal Life and Challenges

Abildgaard's personal life was marked by both joy and sorrow. He married Anna Maria Oxholm in 1781. After her death, he married Juliane Marie Ottesen in 1803. He had several children, but also experienced the pain of loss, including the death of his son Marcus Louis Abildgaard in 1786.

Professionally, the 1794 fire at Christiansborg Palace was a devastating blow. The destruction of years of work, including his monumental history paintings for the Knights' Hall, was not only a personal tragedy but also a significant loss for Danish cultural heritage. This event reportedly plunged him into a period of depression.

Furthermore, his sometimes uncompromising artistic vision and intellectual independence could lead to friction. His art, particularly its darker, more dramatic, or politically suggestive elements, was not always universally acclaimed and sometimes met with criticism for being too academic, too detailed, or lacking in immediate popular appeal compared to the more accessible works of some contemporaries.

Later Years and Death

Despite the challenges, Abildgaard remained a dominant figure in Danish art until his death. He continued his work as Director of the Academy, shaping its curriculum and guiding its students. He also continued to paint and design, though perhaps with less of the monumental ambition that characterized his earlier commissions, partly due to the changing tastes and opportunities.

His health began to decline in his later years. Nicolai Abraham Abildgaard passed away on June 4, 1809, at his country estate, Frederiksdal, near Copenhagen. He was buried in Copenhagen's Assistens Cemetery, a resting place for many of Denmark's most distinguished figures.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Nicolai Abraham Abildgaard's legacy is profound and multifaceted. He is unequivocally recognized as a leading figure of Neoclassicism in Scandinavia and a crucial precursor to Romanticism in the region. His rigorous academic training, combined with his intellectual depth and imaginative power, allowed him to produce a body of work that was both technically accomplished and thematically rich.

His most direct influence was on his students, particularly Thorvaldsen and Eckersberg. Through them, his impact extended throughout the 19th century. Thorvaldsen became an international icon of Neoclassical sculpture, while Eckersberg, by adapting and transforming Abildgaard's teachings, laid the groundwork for the distinctive naturalism and intimate portrayals of Danish life that characterized the Golden Age.

Abildgaard's pioneering exploration of Nordic mythology and Ossianic themes helped to legitimize these subjects within high art, paving the way for later Romantic artists in Scandinavia and Germany who would delve more deeply into national folklore and legend. Artists like Philipp Otto Runge and Caspar David Friedrich, who also had connections to Copenhagen, further developed these Romantic themes.

His contributions to architectural and decorative arts also left a lasting mark, promoting a sophisticated Neoclassical taste in Denmark. The surviving examples of his interior designs and furniture attest to his skill in creating harmonious and elegant environments.

Today, Abildgaard's works are prized possessions of major Danish museums, particularly the Statens Museum for Kunst (National Gallery of Denmark) in Copenhagen. Exhibitions and scholarly research continue to explore the complexities of his art, his intellectual contributions, and his pivotal role in Danish and European art history. He is remembered not just as a painter, but as an intellectual, an educator, and a visionary who helped to define an era and inspire a nation's artistic awakening.

Conclusion

Nicolai Abraham Abildgaard was more than just a painter; he was a cultural force. His mastery of Neoclassical principles, combined with a willingness to explore the emotional depths and imaginative realms of proto-Romanticism, created a unique and powerful artistic voice. His dedication to the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts and his mentorship of a new generation of artists ensured that his influence would resonate long after his death. From the heroic suffering of Philoctetes to the melancholic strains of Ossian, and the lost grandeur of the Christiansborg murals, Abildgaard's art continues to speak to us of an age of profound intellectual and artistic transformation, an age he did much to shape. He remains a cornerstone of Danish art, a vital link between European artistic movements, and a testament to the enduring power of classically informed yet passionately expressed art.