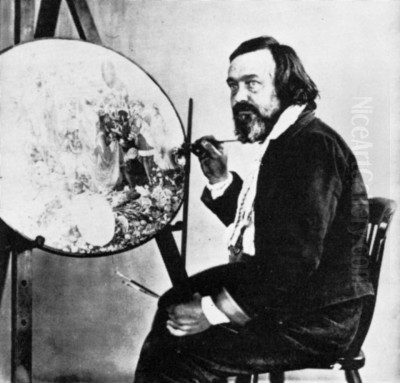

Richard Dadd (1817-1886) remains one of the most intriguing and tragic figures in the history of British art. A painter of prodigious talent, particularly renowned for his exquisitely detailed fairy paintings and Orientalist scenes, Dadd's promising career was irrevocably altered by the onset of severe mental illness, culminating in a shocking act of violence. Confined for the remainder of his life in mental institutions, he continued to produce a body of work that is both captivating and disturbing, offering a unique window into a brilliant mind grappling with profound psychological turmoil. His art, once largely overshadowed by the sensationalism of his life story, has since been re-evaluated, securing his place as a significant, albeit unconventional, contributor to the Victorian art scene.

Early Life and Artistic Promise

Richard Dadd was born on August 1, 1817, in Chatham, Kent. His father, Robert Dadd, was a chemist and pharmacist, and his mother, Mary Ann Dadd (née Martin), was the daughter of a shipwright. This relatively comfortable middle-class upbringing provided a stable foundation for young Richard, who displayed an early aptitude for drawing. The Dadd family was not without its share of tragedy, however, as several of Richard's siblings would later also suffer from mental illness, suggesting a possible genetic predisposition.

By the age of thirteen, Dadd was already receiving some form of artistic instruction, though details from this early period are sparse. His talent was evident enough that his family supported his artistic ambitions. In 1834, the family moved to London, a pivotal step that allowed Richard greater access to the burgeoning art world of the capital. He initially found employment as a draughtsman for an antiquarian, a role that likely honed his skills in precision and detail, which would become hallmarks of his later style.

His formal artistic education began in earnest when, at the age of twenty, in 1837, he was admitted to the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. This was a significant achievement, placing him at the heart of academic art training in Britain. The Royal Academy, then under the presidency of Sir Martin Archer Shee, was the preeminent institution for aspiring artists, and its curriculum emphasized classical principles, life drawing, and the study of Old Masters.

The Royal Academy and "The Clique"

At the Royal Academy Schools, Richard Dadd quickly distinguished himself as a student of exceptional ability. He won several prizes for his drawing and painting, demonstrating a mastery of technique that impressed his tutors and peers alike. It was during this period that he formed close friendships with a group of fellow students who shared his artistic aspirations and, to some extent, a rebellious spirit against the more staid conventions of the Academy.

This group, which came to be known as "The Clique," included notable young artists such as William Powell Frith, who would later achieve immense fame for his panoramic scenes of Victorian life like Derby Day and The Railway Station. Other core members were Augustus Egg, known for his moralizing narrative paintings; Henry Nelson O'Neill, who painted historical and contemporary scenes; and John Phillip, who later became known as "Phillip of Spain" for his vibrant depictions of Spanish life. Alfred Elmore and Edward Matthew Ward were also associated with this circle.

"The Clique" was not a formal movement with a written manifesto, but rather a convivial association of like-minded young men. They met regularly, often in Dadd's lodgings, to sketch, discuss art, and critique each other's work. Their primary shared sentiment was a dissatisfaction with what they perceived as the Royal Academy's overemphasis on idealized historical and mythological subjects, often executed in a grand, but to them, somewhat lifeless manner. They sought subjects more relevant to contemporary tastes and advocated for art that would appeal to a broader public, rather than solely to academic connoisseurs. Their meetings often involved choosing a poetic or literary subject and each artist producing a sketch, fostering a spirit of friendly competition and mutual encouragement.

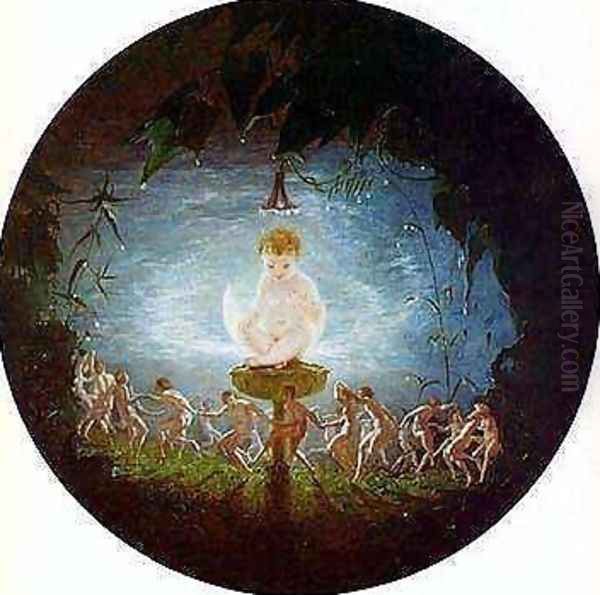

Dadd's early works from this period, such as Titania Sleeping (c. 1841) and Puck (c. 1841), showcased his burgeoning interest in fairy subjects, a genre that was gaining popularity in the Romantic era, partly through the influence of writers like Shakespeare and the visual interpretations of artists such as Henry Fuseli and William Blake. These early fairy paintings by Dadd were characterized by a delicate touch, imaginative compositions, and a growing command of intricate detail.

The Grand Tour: A Fateful Journey

In July 1842, Richard Dadd's career seemed poised for even greater success when he was offered an extraordinary opportunity. Sir Thomas Phillips, a former mayor of Newport and a wealthy lawyer, invited Dadd to accompany him as his personal artist and companion on an extensive Grand Tour. Such tours were a traditional part of a gentleman's education and, for an artist, offered invaluable exposure to the art, culture, and landscapes of Europe and beyond.

Their itinerary was ambitious, taking them through Germany, Switzerland, and Italy, where Dadd would have encountered the masterpieces of the Renaissance and classical antiquity. From Italy, they sailed to Greece, then onward to Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), and into Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey). The journey continued through the Levant, visiting Smyrna, Rhodes, Cyprus, and Beirut, before culminating in an arduous trip up the Nile in Egypt and a journey across the desert to Palestine, visiting Jerusalem and Damascus.

For Dadd, this was an immersive experience. He diligently sketched the landscapes, ancient ruins, and local people they encountered. His drawings and watercolours from this period, such as Caravanserai at Mylasa and views of the Acropolis, demonstrate his keen observational skills and his fascination with the "Orient," a popular theme in 19th-century art, often referred to as Orientalism. Artists like John Frederick Lewis and David Wilkie had already established a British tradition of depicting Middle Eastern scenes, and Dadd was now treading in their footsteps.

However, the rigors of the journey and perhaps the intense cultural experiences began to take a toll on Dadd's mental state. Towards the end of the tour, particularly during their time in Egypt in late 1842 and early 1843, Dadd underwent a profound personality change. He became increasingly erratic, prone to delusions, and exhibited signs of paranoia. He later claimed that he had been possessed by the Egyptian god Osiris and that he was being commanded to perform certain acts. Sir Thomas Phillips grew increasingly concerned by Dadd's behavior, which included moments of aggression.

Descent into Madness and Patricide

Upon their return to England in May 1843, Richard Dadd's mental condition had visibly deteriorated. His family and friends were alarmed by his changed demeanor. He was convinced that his father, Robert Dadd, was an imposter, possibly the devil in disguise, and that he was being persecuted. Despite these clear signs of severe mental illness, the understanding and treatment of such conditions in the mid-19th century were rudimentary.

His family sought medical advice, and it was suggested that he rest in the countryside. On August 28, 1843, while walking with his father in Cobham Park, near Rochester in Kent, Richard Dadd, in a state of acute psychosis, attacked and murdered his father. He stabbed Robert Dadd with a knife and then reportedly used a razor to further mutilate the body. This horrific act, driven by his delusions, marked the tragic turning point in his life.

Following the patricide, Dadd fled to France. He made his way to Calais and then to Paris. His intention, as he later revealed, was to travel to Austria to assassinate the Emperor. While on a train to Montereau, he attempted to attack another passenger with a razor but was overpowered and arrested by the French police. Knives and a list of individuals "who must die" (including his father) were found in his possession.

The French authorities, realizing he was English and clearly insane, contacted the British police. Dadd was extradited to England, where the full extent of his crime became known. He was charged with the murder of his father but was found not guilty by reason of insanity. In August 1844, almost a year after the tragedy, Richard Dadd was committed to the State Criminal Lunatic Asylum section of Bethlem Royal Hospital, popularly known as "Bedlam."

Years of Confinement: Bethlem and Broadmoor

Richard Dadd would spend the next forty-two years of his life institutionalized. He was initially an inmate at Bethlem Royal Hospital in Southwark, London, from 1844 to 1864. Bethlem, despite its notorious historical reputation, was, by this period, under a more enlightened regime, particularly during the superintendency of Dr. William Charles Hood, who took an interest in Dadd's case and encouraged his artistic pursuits.

Life in Bethlem was structured and monotonous, but Dadd was provided with art materials and allowed to paint. This therapeutic engagement with art became his primary focus and solace. He was generally a quiet and cooperative patient, though his delusions persisted. He continued to believe in the influence of Osiris and other supernatural forces, and these beliefs often subtly permeated his artwork.

In 1864, Dadd, along with other "criminal lunatics," was transferred from Bethlem to the newly built Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum in Crowthorne, Berkshire. Broadmoor was designed to house patients who had committed serious offenses while deemed insane. He remained at Broadmoor for the rest of his life, continuing to paint prolifically. The staff at Broadmoor also recognized his talent and provided him with the necessary supplies. He died there on January 7, 1886, from consumption (tuberculosis), at the age of 68. He was buried in the Broadmoor cemetery.

Throughout his long years of confinement, Dadd produced an extraordinary body of work. Far from being diminished by his illness or the institutional environment, his artistic vision seemed to intensify, resulting in paintings of astonishing complexity, detail, and imaginative power.

Masterpieces from the Asylum

The art Richard Dadd created while institutionalized is considered his most significant. Freed from the commercial pressures and academic expectations of the outside art world, he was able to pursue his unique vision with unwavering focus. His style became even more meticulous, his compositions more crowded and intricate, and his subject matter often deeply personal and enigmatic.

Perhaps his most famous work, and a cornerstone of Victorian fairy painting, is The Fairy Feller's Master-Stroke. Painted between 1855 and 1864 while he was at Bethlem, this small oil on canvas (measuring only 54 cm × 39.5 cm) is a work of almost unbelievable detail and complexity. It depicts a dense, microcosmic world of fairies, elves, and fantastical creatures gathered to watch a "fairy feller" (a woodcutter) prepare to split a hazelnut with his axe. Each figure, plant, and insect is rendered with microscopic precision, creating a hallucinatory, almost three-dimensional effect. The painting is accompanied by an elaborate, cryptic poem written by Dadd, titled "Elimination of a Picture & its Subject—called The Feller's Master Stroke," which attempts to identify the myriad characters and their roles, though it often adds to the mystery rather than clarifying it. The work was commissioned by George Henry Haydon, the head steward of Bethlem.

Another significant painting from his Bethlem period is Contradiction: Oberon and Titania (1854-1858). Inspired by Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, this work depicts the quarrel between the fairy king and queen. The scene is packed with an array of tiny, often grotesque, figures, and the atmosphere is one of intense, dreamlike drama. The level of detail is again astonishing, with every leaf and blade of grass meticulously rendered. This painting, like many of Dadd's asylum works, seems to operate on multiple levels, perhaps reflecting his own internal conflicts and the chaotic nature of his thoughts.

During his time at Broadmoor, Dadd continued to produce remarkable works. He painted a series of thirty-three watercolour drawings titled Sketches to Illustrate the Passions (c. 1850s, though some may have been completed at Broadmoor). These include subjects like Grief or Sorrow, Love, Jealousy, Agony-Raving, and Patriotism. These small, intense watercolours explore various emotional states with a raw, unsettling power. He also painted landscapes, often based on his memories of the Middle East or imaginative reconstructions, such as The Flight out of Egypt (1849-50) and numerous watercolour landscapes of an idealized, dreamlike quality.

His portraits from this period are also noteworthy, such as the striking Portrait of a Young Man (c. 1853), believed to be a fellow patient or a staff member at Bethlem. These portraits often possess a haunting intensity and psychological depth.

Artistic Style: Miniaturism, Fantasy, and Orientalism

Richard Dadd's artistic style is highly distinctive, characterized by several key elements that evolved throughout his career but became particularly pronounced during his years of confinement.

Fairy Painting: Dadd is a leading figure in the genre of Victorian fairy painting. While artists like Joseph Noel Paton (The Quarrel of Oberon and Titania) and John Anster Fitzgerald (known for his dreamlike fairy scenes) also excelled in this area, Dadd's approach was unique. His fairy worlds are less sentimental and more unsettling, filled with an almost overwhelming profusion of detail and often imbued with a sense of latent tension or menace. His early fairy works show the influence of artists like Daniel Maclise, whose The Disenchantment of Bottom was a popular success. However, Dadd's later fairy paintings, particularly The Fairy Feller's Master-Stroke, transcend mere illustration to become complex, self-contained universes.

Obsessive Detail and Miniaturism: A defining feature of Dadd's mature style is his meticulous, almost microscopic rendering of detail. He worked with incredibly fine brushes, building up his compositions with tiny, precise strokes. This obsessive attention to detail gives his paintings a jewel-like quality but also contributes to their often claustrophobic and intense atmosphere. This miniaturist approach can be seen as a way of exerting control over his imaginative worlds, or perhaps as a manifestation of his mental state, where every element, no matter how small, held significance.

Orientalism: The Grand Tour left an indelible mark on Dadd's imagination. His sketches and paintings of Middle Eastern subjects, such as Caravanserai at Mylasa, Asia Minor (1845) or The Halt in the Desert (c. 1845), are rendered with the same attention to detail as his fairy paintings. These works contribute to the broader Victorian fascination with the "Orient," but Dadd's interpretations often have a dreamlike, almost surreal quality, filtered through his unique sensibility and, later, his memories.

Literary and Theatrical Influences: Shakespeare, particularly A Midsummer Night's Dream and The Tempest (as seen in his Come Unto These Yellow Sands, c. 1842), was a recurring source of inspiration for Dadd. His art often has a theatrical quality, with figures arranged as if on a stage, and narratives unfolding within complex, layered compositions. His Sketches to Illustrate the Passions also suggest an interest in the dramatic portrayal of human emotion, perhaps influenced by theatrical conventions or philosophical treatises on the passions.

Contemporaries and Influences

Richard Dadd's artistic development occurred within the vibrant and diverse art world of Victorian Britain. His early association with "The Clique" (William Powell Frith, Augustus Egg, Henry Nelson O'Neill, John Phillip, Alfred Elmore, Edward Matthew Ward) placed him among a generation of artists seeking new directions away from the strictures of the Royal Academy, then led by figures like Sir Charles Lock Eastlake. While The Clique's aims were somewhat diffuse, they shared a desire for greater naturalism and subjects that resonated with contemporary audiences, a sentiment that also fueled the slightly later Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (founded 1848), which included Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt.

The genre of fairy painting itself was part of a broader Romantic and Victorian fascination with folklore, mythology, and the supernatural. Earlier artists like Henry Fuseli and William Blake had paved the way with their visionary and often unsettling imagery. Dadd's contemporaries in fairy painting, such as Daniel Maclise, Joseph Noel Paton, and John Anster Fitzgerald, each brought their own interpretations to the genre, but Dadd's work stands apart for its intensity and psychological complexity.

While confined, Dadd was largely isolated from the day-to-day developments of the art world. He would have been unaware of, or only dimly aware of, the rise of Aestheticism or the later Impressionist-influenced movements. His art, therefore, developed along a highly personal trajectory, yet it remains a product of its time, reflecting Victorian anxieties, interests, and imaginative currents. The popular animal painter Sir Edwin Landseer was a dominant figure in the Victorian art scene, representing a very different kind of artistic success compared to Dadd's secluded output.

Legacy and Art Historical Reassessment

For many years after his death, Richard Dadd was known more for the tragic circumstances of his life—the "mad artist who killed his father"—than for his artistic achievements. His works were largely held in private collections or within the archives of Bethlem and Broadmoor. However, the 20th century saw a gradual reassessment of his art.

The rise of Surrealism in the 1920s and 1930s, with its interest in the subconscious, dreams, and the irrational, created a new context for appreciating Dadd's work. Artists and critics began to recognize the visionary power and unique qualities of his paintings. His meticulous detail and fantastical subject matter resonated with a modern sensibility attuned to the complexities of the psyche.

Significant exhibitions, notably a major retrospective at the Tate Gallery in London in 1974, brought Dadd's work to a wider public and solidified his reputation as an important and original artist. This exhibition, curated by art historian Patricia Allderidge, was instrumental in separating the art from the purely sensational aspects of his biography, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of his creative output.

Today, Richard Dadd is recognized as a master of imaginative painting. His work is studied not only for its artistic merit but also for what it reveals about the intersection of creativity and mental illness. While it is tempting to interpret his art solely through the lens of his madness, it is also crucial to acknowledge his exceptional skill, his deep engagement with literary and artistic traditions, and the sheer imaginative force of his vision. His paintings, particularly The Fairy Feller's Master-Stroke, continue to fascinate and perplex viewers, inviting them into intricate worlds that are at once beautiful and disturbing.

Conclusion

Richard Dadd's life was a profound tragedy, yet from the depths of his mental anguish and confinement, he produced art of extraordinary power and originality. He was an artist of immense technical skill, capable of rendering the most minute details with breathtaking precision. His fairy paintings, Orientalist scenes, and psychological portraits offer a unique glimpse into a mind teeming with fantastical imagery and grappling with intense emotional states.

While the shadow of patricide and madness will always be part of his story, Richard Dadd's artistic legacy transcends these biographical details. He stands as a testament to the resilience of the creative spirit and as a singularly compelling figure in the rich tapestry of Victorian art. His work challenges our perceptions of reality, fantasy, and the very nature of artistic creation, ensuring his enduring place in art history as a painter whose brush navigated the complex territories of genius and madness with unforgettable results.