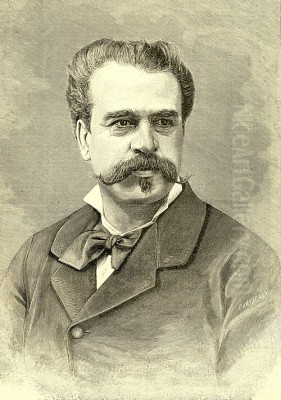

Nicolo Barabino stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the landscape of 19th-century Italian art. An accomplished painter and designer, he dedicated his career to the creation of large-scale works, primarily frescoes and mosaics, that adorned public buildings, churches, and private residences. His art, deeply rooted in historical and religious themes, reflects both the academic traditions of his training and the burgeoning artistic currents of his time. Active from the mid to late 1800s, Barabino's life and work offer a fascinating window into the cultural and artistic aspirations of a newly unified Italy.

Early Life and Genoese Roots

Nicolo Barabino was born in 1832 in Sampierdarena, a town near Genoa, which was then part of the Kingdom of Sardinia. This region, Liguria, with Genoa as its vibrant maritime capital, had a rich artistic heritage, boasting names like Luca Cambiaso in the Renaissance and Bernardo Strozzi in the Baroque period. It was in this environment, steeped in artistic tradition, that Barabino's initial inclinations towards art were nurtured.

His formal artistic education began at the Accademia Ligustica di Belle Arti in Genoa. This institution, like other Italian academies, was dedicated to upholding the classical traditions of art, emphasizing drawing from casts and life, and studying the works of Old Masters. During his time at the Accademia Ligustica, Barabino would have honed his foundational skills in draughtsmanship and composition, essential for the large-scale narrative works that would later define his career. An early, though reportedly difficult, apprenticeship was with Bernardo Castello, a painter of local repute. This relationship is said to have been curtailed due to Castello's jealousy of the young Barabino's burgeoning talent, a testament, perhaps, to Barabino's precocious abilities.

Florentine Sojourn and Artistic Maturation

A pivotal moment in Barabino's development came when he was awarded a scholarship, enabling him to continue his studies in Florence. Florence, the cradle of the Renaissance, remained a vital center for artistic training and inspiration in the 19th century. He enrolled in the prestigious Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze, where he further refined his technique and expanded his artistic horizons. The city itself, with its unparalleled collections of Renaissance art by masters such as Michelangelo, Raphael, and Leonardo da Vinci, provided an immersive learning environment.

In Florence, Barabino was not an isolated student. He formed connections with fellow artists, including the painters Semino and Ernesto Castagnola, and the sculptor Augusto Rivolta. These interactions and shared experiences within the academic setting would have been crucial for his artistic and intellectual growth. The Florentine artistic milieu of the mid-19th century was dynamic. While the Academy upheld traditional teachings, new ideas were also emerging. The Macchiaioli movement, for instance, with key figures like Giovanni Fattori, Telemaco Signorini, and Silvestro Lega, was challenging academic conventions by emphasizing a more direct, sketch-like approach to capturing light and reality, often painting "en plein air."

While Barabino's primary path would lead him towards monumental and often allegorical or historical painting, rather than the intimate realism of the Macchiaioli, the spirit of naturalism and the emphasis on direct observation prevalent in Florence likely informed his work, lending it a vitality that transcended purely academic stiffness. His style began to mature, blending the rigorous discipline of his academic training with a growing sensitivity to color, light, and dramatic composition. It was in Florence that he ultimately decided to settle, establishing it as his primary base, although his commissions would frequently take him back to his native Liguria and beyond.

A Prolific Decorator: Commissions in Genoa and Beyond

Despite making Florence his home, a significant portion of Nicolo Barabino's professional life was dedicated to fulfilling commissions in Genoa. The port city, experiencing economic growth, saw a flourishing of patronage for the arts, particularly for the decoration of its palazzi and public institutions. Barabino became a sought-after artist for these ambitious projects, which often involved extensive fresco cycles.

He undertook significant decorative work in several prominent Genoese residences, including the Palazzo Pignone, Palazzo Orsini, and Palazzo Celsi (sometimes referred to as Palazzo Sauli Celesia). These commissions typically involved creating elaborate allegorical or historical scenes designed to enhance the grandeur of the interiors and reflect the status and cultural aspirations of their owners. Fresco painting, a demanding technique requiring swift and confident execution on wet plaster, was a medium in which Barabino excelled. His works in these palazzi showcased his ability to manage large compositions, his skill in figure drawing, and his rich color palette.

Beyond private residences, Barabino also contributed to public edifices. He was commissioned to execute frescoes for the Genoa City Hall (Palazzo Tursi), a project of considerable civic importance. Such commissions often carried symbolic weight, intended to celebrate the city's history, virtues, or achievements. He also worked on the ceiling decoration for a theatre in Genoa, demonstrating his versatility in applying his artistic vision to different architectural contexts and functional requirements. Theatrical decoration demanded a particular flair for the dramatic and the spectacular, qualities evident in Barabino's broader oeuvre.

His reputation was not confined to Genoa or Florence. Barabino's talents led to commissions and recognition in other parts of Italy and even internationally, with his work known in France, Spain, Belgium, and the Netherlands. This wider reach indicates his standing within the European art scene of the latter 19th century.

The Monumental Mosaics for Florence Cathedral

One of Nicolo Barabino's most prestigious and publicly visible achievements was his contribution to the new facade of Florence Cathedral, Santa Maria del Fiore. The original facade designed by Arnolfo di Cambio had been left unfinished and was eventually dismantled in the 16th century. For centuries, the cathedral presented an undecorated, bare front. In the 19th century, a competition was held to finally complete this iconic structure, won by architect Emilio De Fabris. Barabino was entrusted with designing the cartoons for three large mosaic lunettes above the main portals of this new neo-Gothic facade.

These mosaics, executed by the Venice Art Company (Compagnia Venezia Murano) or workshops associated with Antonio Salviati, a leading figure in the revival of Venetian mosaic art, brought Barabino's designs to life in vibrant, durable tesserae. The subjects chosen were deeply symbolic and resonated with Florence's religious and civic identity:

Over the central portal, the largest mosaic depicted "Christ Enthroned with Mary and John the Baptist." This majestic composition presented Christ in glory, flanked by his mother and the patron saint of Florence, John the Baptist. Such a theme reinforced the cathedral's dedication and its central place in the city's spiritual life.

Above the left portal (looking at the facade), Barabino designed "Charity Among the Founders of Florentine Charitable Institutions" (also known as "La Carità tra i rappresentanti delle Opere pie"). This scene celebrated Florence's long tradition of philanthropy and social welfare, personified by Charity surrounded by figures representing the city's historic benevolent organizations. An oil sketch for this lunette, showcasing Barabino's compositional planning and color choices, is preserved and offers insight into his working process.

Over the right portal, the mosaic illustrated "Faith Among Florentine Artisans, Merchants, and Humanists." This composition paid homage to the diverse groups that had contributed to Florence's economic prosperity, cultural brilliance, and religious devotion throughout its history. It depicted Faith surrounded by representatives of the city's guilds, its commercial enterprises, and its intellectual pioneers.

These mosaics, completed in the late 1880s, were a significant undertaking. They required Barabino to work on a grand scale, ensuring his designs were legible from a distance and harmonized with De Fabris's intricate architectural framework. The choice of mosaic, an ancient and enduring medium, was fitting for a monument of such importance, and Barabino's designs successfully blended traditional iconography with a 19th-century sensibility. Despite their prominent location, these works are sometimes cited as examples of Barabino's contributions that, while significant, may not have achieved the widespread popular fame of some other contemporary artistic endeavors.

Artistic Style, Influences, and Thematic Concerns

Nicolo Barabino's artistic style can be characterized as a sophisticated blend of academic classicism, Romantic sensibility, and a degree of realism. His training instilled in him a strong command of anatomy, perspective, and composition, hallmarks of the academic tradition championed by artists like Vincenzo Camuccini or Francesco Hayez in earlier parts of the century. However, his work was not merely a sterile imitation of past models.

There is a distinct dramatic quality to many of Barabino's compositions, a flair for narrative, and an emotional intensity that aligns with Romanticism. This is evident in his choice of historical and religious subjects, often imbued with a sense of grandeur or pathos. His color palettes were typically rich and vibrant, contributing to the visual impact of his large-scale frescoes and mosaics. He was adept at conveying movement and expression in his figures, bringing his narrative scenes to life.

Influences on his style were varied. The legacy of Italian Renaissance and Baroque masters was, of course, foundational. The grandeur of Michelangelo, the grace of Raphael, and the dramatic chiaroscuro of Caravaggio or the Genoese Bernardo Strozzi, formed part of the artistic DNA of any Italian painter of his era. The provided information also suggests an influence from Northern European prints, which might have contributed to his narrative clarity or compositional strategies.

His time in Florence, as mentioned, exposed him to the currents of realism, particularly the Macchiaioli. While he did not adopt their technique wholesale, the emphasis on truth to nature and direct observation likely tempered any tendency towards excessive idealism in his figures and settings. His work sought a balance between the ideal and the real, the grand and the human.

Barabino's thematic concerns were predominantly historical and religious. He depicted scenes from the Bible, lives of saints, and significant moments from classical or Italian history. These themes were well-suited to the public and ecclesiastical commissions he frequently received. His role as a decorator often required him to create allegorical figures representing virtues, arts, or sciences, a common feature in the decorative programs of 19th-century public buildings and palazzi.

Other Notable Works and Stage Design

Beyond his major fresco cycles and the Florence Cathedral mosaics, Barabino produced numerous other paintings. One such work, a "Madonna and Child" (Madonna e Bambino), gained a poignant afterlife. A prayer card featuring a reproduction of this painting reportedly served as an inspiration for Domenico Chiocchetti, an Italian prisoner of war during World War II, when he undertook the decoration of the Italian Chapel in Lamb Holm, Orkney Islands. This small, touching connection demonstrates the far-reaching and sometimes unexpected impact an artist's work can have.

Barabino was also active as a stage designer. In the 19th century, stage design was a significant artistic field, often attracting talented painters. The opera and theatre were central to cultural life, and elaborate, illusionistic stage sets were in high demand. This aspect of his career would have allowed him to indulge his penchant for dramatic compositions and grand visual effects, skills that were transferable to his mural and ceiling paintings. Artists like Alessandro Sanquirico had earlier set a high standard for Italian stage design, and Barabino would have been part of this continuing tradition.

His involvement in various exhibitions and the inclusion of his works in auction catalogues of the time further attest to his activity and recognition within the art market and among collectors. He was a working artist navigating the professional landscape of his era, which included academic circles, private patronage, and public commissions.

Contemporaries and the Italian Art Scene

Nicolo Barabino operated within a vibrant and evolving Italian art world. The 19th century in Italy was a period of profound political change, culminating in the Risorgimento and the unification of the country. This national rebirth had a corresponding impact on the arts, with debates about national identity, the role of tradition, and the embrace of modernity.

In the realm of historical and religious painting, artists like Francesco Hayez had dominated the earlier part of the century with their Romantic interpretations. Later, figures like Domenico Morelli and Stefano Ussi continued to explore historical and literary themes, often with a greater emphasis on realism and psychological depth. Barabino's work can be seen as part of this lineage, maintaining a commitment to grand narrative painting even as other movements gained traction.

The Macchiaioli, including Giovanni Fattori, Telemaco Signorini, and Silvestro Lega, represented a significant departure towards realism and plein-air painting. While Barabino's path was different, their presence in Florence contributed to a diverse artistic ecosystem. Other artists focused on genre scenes, like Gerolamo Induno, or portraiture, which saw the rise of figures like Giovanni Boldini, who later achieved international fame in Paris.

In sculpture, contemporaries like Giovanni Duprè upheld classical ideals, while others like Vincenzo Gemito embraced a more intense realism. Barabino's collaborator on the Florence Cathedral facade, the architect Emilio De Fabris, was a key figure in 19th-century Italian architecture. The mosaicists who translated his cartoons, such as those from the Salviati workshops in Venice, were part of a major revival of that ancient art form.

Barabino's academic training connected him to a network of artists and teachers. His fellow students in Florence, Semino and Castagnola, and the sculptor Augusto Rivolta, were part of his immediate circle. The influence of the Florentine Academy also connected him to figures like Domenico Felli and Mario Delogu, who were considered part of the development of modern Italian painting stemming from that institution. His early, albeit brief, association with Bernardo Castello in Genoa places him within the local artistic lineage there. The mention of Giuseppe Pellizzella as a teacher and friend to an Angelo Barabino (potentially a relative or a confusion in records) highlights the interconnectedness of regional art circles.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Nicolo Barabino died in Florence in 1891. His passing was noted at the time as a significant loss to the Italian art world, indicative of the respect he commanded during his lifetime. He was recognized as a skilled and prolific painter, a master of large-scale decorative schemes, and a contributor to some of the most important artistic projects of his era, notably the Florence Cathedral facade.

In the broader sweep of art history, 19th-century academic and monumental painters have sometimes been overshadowed by the avant-garde movements that followed. However, there has been a growing scholarly interest in reassessing the contributions of artists like Barabino, who successfully navigated the demands of public and private patronage and upheld a high standard of craftsmanship. His work represents a significant strand of 19th-century Italian art, one that sought to synthesize tradition with contemporary sensibilities.

His frescoes and mosaics continue to adorn the buildings for which they were created, serving as tangible links to the cultural aspirations of post-Unification Italy. They speak of a desire for beauty, for historical commemoration, and for the expression of civic and religious values through art. While perhaps not a radical innovator in the mold of the Impressionists or Post-Impressionists who were his contemporaries elsewhere in Europe, Barabino was a highly accomplished artist who made a substantial contribution to the visual culture of his nation. His dedication to monumental art, his technical skill, and the sheer volume of his output secure his place as an important figure in the story of 19th-century Italian painting.

Conclusion: An Enduring Contribution

Nicolo Barabino's career spanned a transformative period in Italian history and art. From his early training in Genoa to his mature works in Florence and beyond, he remained committed to the power of large-scale narrative and decorative painting. His frescoes in Genoese palazzi, his designs for the magnificent mosaics of Florence Cathedral, and his numerous other religious and historical works testify to a prolific talent and a deep understanding of his craft.

He successfully blended academic discipline with a Romantic sensibility and an awareness of contemporary realistic trends, creating a style that was both grand and accessible. While the tides of art history have often favored more revolutionary figures, Nicolo Barabino's substantial body of work remains an important testament to the enduring appeal of monumental art and its capacity to shape public and private spaces. As an artist who dedicated his life to beautifying churches, civic buildings, and homes, his legacy is etched into the very fabric of the cities he served, a quiet but persistent voice from Italy's vibrant 19th-century artistic past.