Sir William Blake Richmond (1842-1921) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of late Victorian and early Edwardian art. A painter of remarkable versatility, he excelled in portraiture, mythological subjects, and, most notably, large-scale decorative schemes, particularly mosaics. His career was marked by a deep reverence for the Italian Renaissance masters, a commitment to the ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement, and a surprising foray into environmental activism. This exploration delves into the life, work, and enduring legacy of an artist who navigated the complex currents of his time with skill and conviction.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Born in Marylebone, London, on November 29, 1842, William Blake Richmond was immersed in art from his earliest days. He was the son of George Richmond, a distinguished portrait painter and a member of "The Ancients," a group of artists who gathered around the visionary poet and artist William Blake. Indeed, William Blake Richmond was named in honor of this seminal figure, whose spiritual and imaginative approach to art profoundly influenced George Richmond and his circle, which included Samuel Palmer and Edward Calvert. This artistic lineage provided young William with an unparalleled early education in art, not just in technique but in aesthetic philosophy.

His formal training began at an early age. By 1857, at just fourteen, he was enrolled in the Royal Academy Schools. Here, he demonstrated prodigious talent, absorbing the rigorous academic curriculum. His time at the Schools was formative, providing him with the technical grounding that would underpin his diverse artistic output. He was a contemporary of artists who would also make their mark, though his path would diverge from the more radical Pre-Raphaelites like Dante Gabriel Rossetti or John Everett Millais, who had challenged the Academy's teachings a decade earlier.

The Italian Sojourn and Renaissance Ideals

A pivotal moment in Richmond's artistic development came in 1859 with his first visit to Italy. This journey, a traditional rite of passage for aspiring artists, was a profound revelation for him. He spent considerable time studying the works of the Old Masters, particularly those of the Italian Renaissance. Artists like Giotto, Fra Angelico, and Michelangelo captivated him with their grandeur, spiritual depth, and mastery of form. He was particularly drawn to the Venetian school, with the rich colours and dramatic compositions of Titian and Giorgione leaving an indelible mark on his artistic sensibility.

This immersion in Italian art was not a fleeting affair. Richmond would return to Italy frequently throughout his life, living there for extended periods. These experiences deepened his understanding of classical and Renaissance principles, which he sought to integrate into his own work. He was less interested in the meticulous realism of some of his contemporaries and more drawn to the idealised forms and harmonious compositions he found in Italian art. This classical leaning would set him somewhat apart from the prevailing trends in British art, yet it also provided the foundation for his most ambitious projects. He also encountered contemporary Italian artists, such as Giovanni Costa, whose landscape paintings and artistic circle, the "Etruscan School," shared a commitment to direct observation and a poetic interpretation of nature, which resonated with Richmond's own developing aesthetic.

A Flourishing Career in Portraiture

Upon his return to England, Richmond began to establish himself as a portrait painter. His father's reputation undoubtedly opened doors, but William's own skill quickly became apparent. He possessed a talent for capturing not only a likeness but also the character and social standing of his sitters. His portraits from this period are characterized by their elegance, refined technique, and often, a subtle psychological insight.

He painted many prominent figures of Victorian society, including politicians, aristocrats, and fellow artists. His sitters included William Gladstone, Otto von Bismarck, Robert Browning, and Charles Darwin. These portraits demonstrate his ability to adapt his style to the personality of the subject, ranging from formal and imposing to more intimate and reflective. While adhering to the conventions of society portraiture, Richmond often imbued his works with a richness of colour and a sense of dignity that harked back to his Renaissance exemplars. His success in this genre provided him with financial stability and a prominent position in the London art world. He exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy, where his first painting was shown in 1861, and later at the Grosvenor Gallery, a more progressive venue favoured by artists like Edward Burne-Jones and James McNeill Whistler.

Mythological and Allegorical Canvases

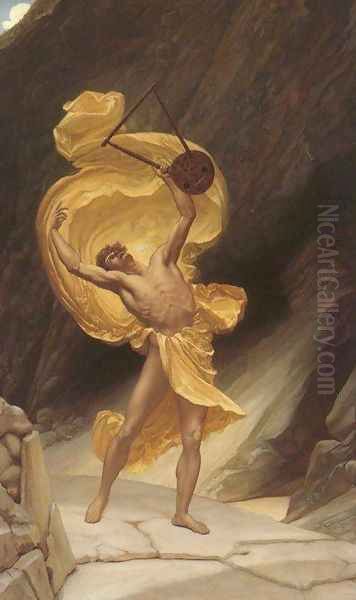

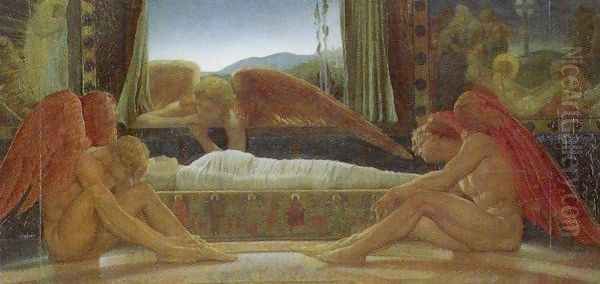

Beyond portraiture, Richmond was deeply engaged with mythological, biblical, and allegorical themes. These subjects allowed him to explore his interest in the human form, dramatic narrative, and symbolic meaning. His classical education and his studies in Italy provided a rich wellspring of inspiration for these works. Paintings such as The Song of Miriam (1860s), Hercules Releasing Prometheus, and The Watchers demonstrate his ambition to create grand, heroic compositions in the tradition of the Old Masters.

His mythological paintings often feature dynamic compositions, idealized figures, and a rich, sometimes somber, palette. Works like The Love of Aphrodite and Anchises (1889) and Hera in the House of Hephaestus (1890) showcase his ability to render complex narratives with a sense of drama and sensuousness. Orpheus Returning from the Shades (1885) is another powerful example, capturing the tragic moment with emotional intensity. These paintings reflect the Victorian fascination with classical antiquity but are filtered through Richmond's distinctive artistic lens, which often incorporated elements of Symbolism. He was a contemporary of other artists exploring similar themes, such as Lord Frederic Leighton and George Frederic Watts, often dubbed "England's Michelangelo," both of whom also looked to classical and Renaissance art for inspiration.

One particularly striking work is The Slave (1886), which, while potentially alluding to classical themes of servitude, also carries a contemporary resonance with its depiction of a powerful, yet enchained, female figure. This painting, with its strong modeling and emotional weight, exemplifies Richmond's ability to blend classical aesthetics with a more modern sensibility. Similarly, Adam and Eve Expelled from Paradise (1886) tackles a biblical subject with dramatic force and a focus on human emotion.

The St. Paul's Cathedral Mosaics: A Monumental Achievement

Perhaps Richmond's most enduring and certainly his most publicly visible legacy is his extensive mosaic work in St. Paul's Cathedral, London. Commissioned in 1891, this vast undertaking occupied him for over a decade and involved decorating the choir, apse, and ambulatory with intricate glass mosaics. This project was a departure from the cathedral's original, more austere, Wren-designed interior and represented a significant intervention in one of Britain's most iconic buildings.

Richmond approached this monumental task with characteristic energy and a deep understanding of historical mosaic techniques. He drew heavily on Byzantine and early Christian art, particularly the mosaics of Ravenna and Venice, for inspiration. He believed that mosaic was the ideal medium for ecclesiastical decoration, offering a richness of colour and a shimmering, ethereal quality that paint could not achieve. He collaborated closely with the renowned glass manufacturers James Powell & Sons of Whitefriars to develop new types of glass with a wider range of colours and textures, specifically suited to his designs. This collaboration was crucial to the success of the project and reflects Richmond's engagement with the principles of the Arts and Crafts movement, which emphasized the integration of art and craftsmanship.

The St. Paul's mosaics are characterized by their bold designs, vibrant colours – particularly deep blues, greens, and golds – and strong, stylized figures. The subjects depict scenes from the life of Christ, saints, and allegorical figures, all rendered in a style that is both monumental and decorative. The project was not without controversy. Some critics and members of the public felt that the opulent, colourful mosaics were out of keeping with the cathedral's Protestant traditions and Wren's more restrained architectural vision. Debates raged in the press about the appropriateness of introducing such a "Mediterranean" or "Catholic" aesthetic into an Anglican cathedral. Despite these criticisms, Richmond persevered, and the mosaics remain a stunning, if debated, feature of St. Paul's. They represent a significant contribution to the revival of mosaic art in Britain and stand as a testament to Richmond's ambition and artistic vision.

Engagement with the Arts and Crafts Movement

Richmond's work on the St. Paul's mosaics, with its emphasis on craftsmanship, decorative quality, and the integration of art into architecture, aligns him closely with the ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement. While not as centrally involved as figures like William Morris or Walter Crane, Richmond shared their belief in the importance of high-quality materials, skilled workmanship, and the social value of art. His development of new glass types with Powell & Sons is a clear example of this practical engagement with craft.

He believed that art should not be confined to galleries but should enrich public spaces and everyday life. His decorative schemes, which extended beyond St. Paul's to other churches and public buildings, reflect this conviction. The Arts and Crafts emphasis on reviving traditional techniques and elevating the status of the decorative arts found a sympathetic practitioner in Richmond, whose own work often blurred the lines between fine art and applied art. His commitment to beauty and craftsmanship resonated with the movement's desire to counteract the perceived ugliness and shoddiness of mass-produced industrial goods.

Academic Life: The Slade Professorship and a Clash with Ruskin

Richmond's standing in the art world was further recognized by his appointment as Slade Professor of Fine Art at the University of Oxford in 1878, succeeding John Ruskin. This was one of the most prestigious academic positions in art in Britain. During his tenure, which lasted until 1883, he lectured on art history and theory, drawing on his extensive knowledge of the Italian masters.

His time at Oxford, however, was not without its challenges. Richmond held Michelangelo in the highest esteem, considering him the pinnacle of artistic achievement. This view clashed with that of his predecessor, John Ruskin, who, while initially an admirer, had become increasingly critical of Michelangelo and the High Renaissance, favoring instead earlier Italian art and Gothic architecture. This difference in artistic philosophy led to friction, and Richmond ultimately resigned from the professorship. Despite this, his period at Oxford demonstrates his intellectual engagement with art and his commitment to art education. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1888 and a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1895, further cementing his position within the British art establishment.

Social Activism: The Campaign Against Air Pollution

Beyond his artistic endeavors, Sir William Blake Richmond was a passionate and pioneering environmental campaigner. Living and working in London, he became increasingly concerned about the detrimental effects of coal smoke pollution on the city's air quality, public health, and historic buildings – including his own mosaics in St. Paul's, which were being discolored by soot.

In 1898, he founded the Coal Smoke Abatement Society, one of the earliest environmental organizations in Britain. As its president, he campaigned vigorously for cleaner air, advocating for stricter regulations on coal burning and the adoption of cleaner technologies. He gave lectures, wrote articles, and lobbied parliament, highlighting the dangers of air pollution long before it became a mainstream concern. This activism demonstrates a remarkable foresight and a commitment to public welfare that extended beyond the realm of art. His efforts laid the groundwork for future environmental legislation and mark him as an important, if often uncredited, figure in the history of environmentalism.

Anecdotes and Personal Life

Richmond's life was rich with experiences that shaped his art and worldview. His early and repeated visits to Italy were not just artistic pilgrimages but also deeply personal journeys. One often recounted story tells of his encounter with an Italian shepherd boy named Beppino during one of his stays. Richmond was captivated by the boy's natural grace and beauty, and this encounter seems to have symbolized for him the enduring connection between humanity and the classical landscape. Years later, he reportedly returned to Italy hoping to find Beppino, only to learn of his passing, an experience that deeply affected him.

His strong opinions and passionate nature sometimes led to public debate, as seen with the St. Paul's mosaics and his differences with Ruskin. The controversy surrounding his description of William Blake's death, which some scholars have questioned for its romanticized portrayal, also hints at a personality inclined towards the dramatic and the idealized. These aspects of his character, however, also fueled his artistic ambition and his commitment to his various causes.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Richmond moved within a vibrant artistic and intellectual milieu. His father's connections to "The Ancients" like Samuel Palmer and Edward Calvert provided an early link to a visionary tradition in British art. As he matured, he interacted with many of the leading figures of the Victorian art world. While his classical leanings and decorative focus set him apart from the narrative realism of some Royal Academicians or the avant-garde experiments of Whistler, he was a respected member of the establishment.

His relationship with John Ruskin was complex, marked by mutual respect for their respective positions but also by fundamental disagreements on artistic principles. His collaborations, such as with Powell & Sons for the St. Paul's mosaics, highlight his ability to work with skilled artisans to achieve his artistic vision. He exhibited alongside artists like Edward Burne-Jones and G.F. Watts at the Grosvenor Gallery, indicating a shared interest in imaginative and symbolic art, even if their styles differed. The artistic landscape of Victorian England was diverse, and Richmond carved out a distinctive niche within it, drawing on tradition while also embracing new possibilities in decorative art.

Later Years and Legacy

Sir William Blake Richmond continued to work and exhibit into the early 20th century. He was knighted (KCB) in 1897 in recognition of his artistic achievements, particularly his work at St. Paul's. He remained active in the Coal Smoke Abatement Society and continued to paint portraits and other subjects. He passed away on February 11, 1921, in Hammersmith, London, leaving behind a substantial body of work and a multifaceted legacy.

In the decades following his death, Richmond's reputation, like that of many Victorian artists, experienced a period of decline as modernist aesthetics came to dominate. However, a renewed appreciation for Victorian art in the late 20th and early 21st centuries has led to a re-evaluation of his contributions. His portraits are recognized for their skill and insight. His mythological and allegorical paintings are seen as important examples of late Victorian classicism and symbolism. His pioneering environmental activism is increasingly acknowledged as remarkably prescient.

Above all, the St. Paul's Cathedral mosaics remain his most visible and debated legacy. They stand as a bold and ambitious attempt to fuse Byzantine grandeur with Victorian sensibility, transforming one of London's most iconic spaces. While opinions on their aesthetic success may still vary, their significance as a major work of decorative art and a testament to Richmond's artistic vision is undeniable.

Conclusion: A Man of Many Talents

Sir William Blake Richmond was more than just a painter; he was an artist of broad vision, a dedicated craftsman, an intellectual, and a passionate advocate for social improvement. His art, rooted in a deep appreciation for the classical tradition, particularly the Italian Renaissance, evolved to embrace the decorative possibilities championed by the Arts and Crafts movement. From elegant portraits of the Victorian elite to the monumental, shimmering mosaics of St. Paul's Cathedral, his work demonstrates a remarkable range and ambition.

His commitment to beauty extended beyond the canvas and the cathedral wall to the very air Londoners breathed, making him a pioneer in environmental activism. While he may not have achieved the household-name status of some of his contemporaries like Dante Gabriel Rossetti or William Morris, Sir William Blake Richmond's contributions to British art and society were substantial and deserve continued recognition. He remains a compelling figure, embodying the complexities, contradictions, and creative energy of the Victorian era.