Nikolai Nikolaevich Karazin (1842–1908) stands as a remarkable figure in the cultural and historical landscape of 19th-century Russia. His life was a tapestry woven with threads of military service, artistic creation, literary pursuits, and pioneering ethnographic exploration. Unlike many of his contemporaries who dedicated themselves solely to the studio, Karazin was a man of action, whose experiences on the battlefield and in remote territories of the Russian Empire directly fueled his creative output. He was a painter, a prolific illustrator, a writer, and an observer of cultures, leaving behind a rich legacy that offers invaluable insights into the Russia of his time, particularly its expansion into Central Asia and the diverse peoples it encountered.

A Formative Heritage and Early Military Path

Born on December 9, 1842, in the Kharkov Governorate (now Ukraine), Nikolai Karazin hailed from a family with a notable intellectual and public service background. His great-grandfather, Vasily Nazarovich Karazin, was a prominent Enlightenment figure, a scientist, inventor, and, crucially, the founder of Kharkiv University, not Kyiv University as sometimes mistakenly cited. Vasily Karazin was known for his progressive ideas and even faced imprisonment in 1820 for his critiques of Tsar Alexander I's regime, a historical detail sometimes incorrectly attributed to Nikolai. This familial legacy of intellectual curiosity and a willingness to engage with the pressing issues of the day undoubtedly shaped young Nikolai's worldview.

Nikolai Nikolaevich Karazin's early education was geared towards a military career. He graduated from the Moscow Second Cadet Corps in 1862. His initial artistic inclinations led him to briefly study at the Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg between 1865 and 1867. However, the structured academic environment perhaps did not fully align with his adventurous spirit, and his formal art training remained relatively limited compared to many of his peers who spent years within the Academy's walls.

His military career commenced in earnest, and he participated in several significant campaigns. He was involved in suppressing the Polish Uprising of 1863-1864. More consequentially for his artistic development, he served in the military expeditions to Central Asia during the 1860s and 1870s, a period of intense Russian expansion into regions like Turkestan. These campaigns, including the conquest of Tashkent and Samarkand, provided him with firsthand experiences of warfare, diverse cultures, and dramatic landscapes that would become central themes in his art. He also served as a military correspondent and commander during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, further broadening his exposure to conflict and its human dimensions.

The Artist Forged in Experience: Central Asia and Beyond

Karazin's time in Central Asia was transformative. He was not merely a soldier but an astute observer. The vast steppes, the ancient cities, the vibrant attire, and the distinct customs of the Kazakh, Uzbek, Turkmen, Tajik, and Karakalpak peoples captivated him. He began to sketch and paint prolifically, documenting what he saw with an eye for both ethnographic detail and artistic composition. His works from this period are invaluable historical records, offering visual testimony to a world undergoing profound change as the Russian Empire asserted its influence.

His role evolved into that of a "soldier-artist," a chronicler of the Empire's reach. He documented military engagements, but also the daily life, rituals, and environments of the local populations. This dual focus—the imperial project and the indigenous cultures—is a defining characteristic of his Central Asian oeuvre. He developed a keen ability to capture the unique atmosphere of the region, from the harshness of the desert to the bustling life of oasis towns.

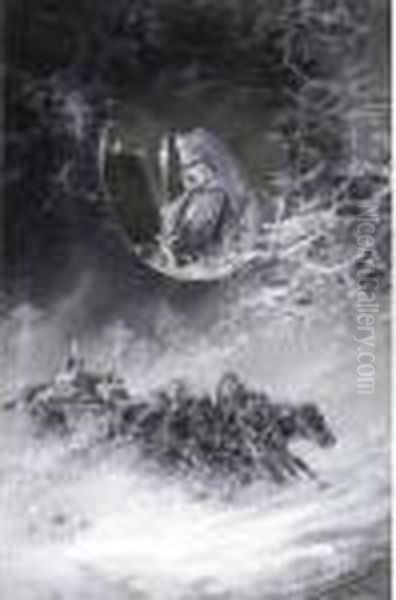

Karazin's artistic output was diverse in medium, though he became particularly renowned for his watercolors and illustrations. He also worked in oils, creating larger-scale battle paintings and genre scenes. His style was predominantly realistic, emphasizing accuracy in the depiction of uniforms, weaponry, ethnic attire, and architectural details. This commitment to veracity was essential for his role as a visual correspondent and ethnographer.

Signature Works and Thematic Concerns

Several works stand out in Karazin's extensive portfolio, reflecting his primary thematic interests: military history, ethnography, and the natural world.

His battle paintings, such as "The Capture of Tashkent" (also known as Taškent’s Capture) and "Russian Troops Take Samarkand" (1868), are dramatic depictions of key moments in the Russian conquest of Central Asia. These works often emphasize the discipline and might of the Russian forces while also capturing the exoticism of the setting and the resistance of the local defenders. One version of Russian Troops Take Samarkand (1868) found its way from a private collection to the State Russian Museum, highlighting its perceived importance.

Ethnographic accuracy was paramount in works depicting local life. Paintings and illustrations of Kazakh nomads, Uzbek merchants, or Turkmen warriors are rendered with careful attention to traditional clothing, jewelry, and daily activities. For instance, his watercolor "Cossack on Horseback" (though Cossacks are distinct from Central Asian Kazakhs, Karazin depicted various mounted figures of the Empire) showcases his skill in rendering figures and horses with dynamism and precision, often highlighting the unique gear and spirit of these frontier horsemen. He also produced a significant series of watercolors documenting the history of the Siberian Cossacks, which was reportedly created for Tsar Nicholas II, underscoring his connection to the imperial court and its interest in the visual chronicling of the Empire's history.

Beyond military and ethnographic scenes, Karazin had a keen interest in the natural world. His book and accompanying illustrations, "From North to South: Memoirs of an Old Crane" (1898), which poetically documents the migration of cranes from the Valdai Hills to Egypt, reveals a more lyrical and observational aspect of his talent. This work, blending natural history with artistic interpretation, was highly popular.

His literary and illustrative work on Central Asian folklore, such as his contributions to understanding Karakalpak tales, including the collection sometimes referred to as "Karakalpak Fairy Tales," and his adventure narratives like "Pogonia za Nazhivou" (Pursuit of Profit/Loot), further cemented his reputation. These works often combined thrilling narratives with rich visual descriptions and illustrations, creating a unique genre of "adventure ethnography."

Artistic Style, Techniques, and Influences

Nikolai Karazin's artistic style is best characterized as a form of Realism with strong ethnographic and documentary underpinnings. Having had a relatively brief formal training at the Imperial Academy of Arts, his technique was largely honed through direct observation and practice in the field. This gave his work an immediacy and authenticity, particularly in his sketches and watercolors.

His draftsmanship was precise, essential for capturing the intricate details of military uniforms, ethnic costumes, and architectural elements. He had a good understanding of anatomy, particularly for horses, which feature prominently in his military and genre scenes. His use of color was often vibrant, reflecting the bright textiles and sun-drenched landscapes of Central Asia, though he could also employ more somber palettes for dramatic battle scenes or specific atmospheric effects.

In his illustrations, Karazin demonstrated a remarkable ability for dynamic composition and narrative clarity. He was a prolific illustrator for popular periodicals of the time, such as Niva (The Field) and Vsemirnaya Illyustratsiya (Worldwide Illustration), bringing news, travel accounts, and fiction to a wide readership. His illustrative style was often compared to that of the French master Gustave Doré, whose dramatic and detailed engravings were internationally renowned. Indeed, some sources suggest Karazin may have even briefly studied or sought guidance from Doré or engravers like Firmin Gillot in Paris, which would account for the sophisticated graphic quality in some of his work. This connection, however, needs careful consideration, as being a "competitor" to Doré, as sometimes claimed, is a significant assertion given Doré's global stature. It's more likely Karazin admired and learned from Doré's widely circulated illustrative techniques.

While not a member of the Peredvizhniki (The Wanderers) movement, which dominated the Russian art scene with its focus on social realism and national subjects, Karazin shared their commitment to depicting Russian life and landscapes, albeit often from the Empire's periphery. His focus on military glory and ethnographic documentation aligned more with official imperial interests than the critical social commentary often found in Peredvizhniki works by artists like Ilya Repin or Vasily Perov.

His primary artistic peer and, in some ways, a rival in the depiction of Central Asian and battle subjects was Vasily Vereshchagin. Both artists traveled extensively in Central Asia and documented military campaigns. However, Vereshchagin's work often carried a more overt anti-war message and a starker, more critical portrayal of the realities of conflict, whereas Karazin's depictions, while realistic, sometimes leaned towards a more heroic or picturesque representation, though he did not shy away from the drama of combat.

Literary and Ethnographic Contributions

Beyond his visual art, Nikolai Karazin was a significant writer and ethnographer. His travels and military experiences provided rich material for numerous books, articles, and stories. He possessed a lively narrative style, and his writings, often illustrated by himself, were popular with the Russian public, offering them glimpses into the remote and newly acquired territories of the Empire.

His ethnographic contributions were particularly noteworthy. He collected folklore, described customs, and documented the material culture of various Central Asian peoples. His work on the Karakalpaks, for example, including his efforts to record their oral traditions and tales, was an important early contribution to the study of this group. Works like Pogonia za Nazhivou and other travelogues combined adventure with detailed observations of local life, effectively popularizing ethnographic knowledge.

These literary and ethnographic endeavors were part of a broader Russian intellectual movement known as Vostokovedeniye (Oriental Studies). Karazin, through his accessible writings and vivid illustrations, played a role in shaping the Russian popular imagination of "the Orient," particularly Central Asia. His work contributed to both a romanticized view of these lands and peoples and a more concrete understanding of their cultures, albeit often framed within the context of imperial expansion. He was, in essence, a cultural mediator, translating his experiences in these "exotic" locales for a Russian audience.

Karazin and His Artistic Contemporaries

Nikolai Karazin operated within a vibrant and diverse Russian art world. While his path was somewhat unique due to his military career, his work can be understood in relation to several key contemporaries and artistic trends.

The most significant comparison, as mentioned, is with Vasily Vereshchagin (1842-1904). Both were soldier-artists who gained fame for their depictions of Central Asia and warfare. Vereshchagin's Turkestan series, with its unflinching realism and often critical undertones, set a high bar for Orientalist and battle painting. Karazin’s work, while also detailed, often had a more illustrative or romantic quality.

In the realm of battle painting, other notable Russian artists of the period or slightly later included Franz Roubaud (1856-1928), famous for his vast panoramas like "The Siege of Sevastopol" and "The Battle of Borodino," and Mykola Samokysh (Nikolai Samokish, 1860-1944), who also specialized in military scenes and depictions of Cossack life, continuing a tradition Karazin contributed to. Alexey Bogolyubov (1824-1896), primarily a marine painter, also depicted scenes from the Russo-Turkish War and was an influential figure in the Academy.

The broader context of Russian Realism was dominated by the Peredvizhniki. Artists like Ilya Repin (1844-1930), with his powerful historical canvases and portraits, and Vasily Surikov (1848-1916), known for his dramatic scenes from Russian history, represented the pinnacle of this movement. While Karazin's subject matter often differed, he shared their commitment to realistic representation. Viktor Vasnetsov (1848-1926), another prominent figure, focused on mythological and historical folklore, offering a different facet of Russian national identity in art.

For equine and genre scenes involving Cossacks and hunting, Nikolai Sverchkov (1817-1898) was an established master whose work would have been known to Karazin. The depiction of horses was crucial for both artists.

Internationally, the genre of Orientalist painting was flourishing, with French artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904) creating highly detailed and often romanticized scenes of the Middle East and North Africa. Karazin's work can be seen as a Russian counterpart to this European tradition, adapted to the specific context of Russian Central Asia.

As an illustrator, Karazin's prolific output can be compared to that of Gustave Doré (1832-1883) in terms of industry and popular appeal, though their styles differed. Within Russia, illustrators like Elena Polenova (1850-1898), who was also involved in the revival of folk art, and later Ivan Bilibin (1876-1942), with his iconic style for fairy tales, represented the rich tradition of Russian book art. Karazin was a key figure in popular, periodical illustration.

Even artists with different stylistic leanings, like the Symbolist Mikhail Vrubel (1856-1910), were part of the artistic landscape Karazin navigated. The late 19th century was a period of artistic ferment, and Karazin carved out his niche through his unique blend of direct experience and artistic skill.

Later Life, Recognition, and Legacy

Nikolai Karazin remained active as an artist and writer throughout his life. His works were widely exhibited, and he received recognition for his contributions. He was a corresponding member of the Imperial Academy of Arts and was involved with various geographical and ethnographic societies, reflecting his diverse interests.

His political views, unlike those of his great-grandfather Vasily, appear to have been more aligned with the prevailing imperial sentiment, or at least less overtly critical. His relationship with figures like Tsar Alexander II was reportedly good, and his art often served to document and, implicitly, legitimize Russian presence in newly acquired territories. The story of his arrest in 1820 for criticizing Tsar Alexander I is a conflation with his great-grandfather's biography; Nikolai Karazin lived and worked under Tsars Alexander II, Alexander III, and Nicholas II.

Nikolai Nikolaevich Karazin passed away on December 19, 1908 (some sources state December 31 or use the Old Style date of December 18), in Gatchina, near St. Petersburg, at the age of 66.

His legacy is multifaceted. As an artist, he left an extensive visual record of military campaigns, Central Asian life, and Russian landscapes. His paintings and illustrations are valuable historical documents, prized for their ethnographic detail and artistic merit. His works are held in major Russian museums, including the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg and the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, as well as the Russian State Library (which holds a significant collection of his Siberian Cossack watercolors), and numerous regional museums and private collections. For example, besides Russian Troops Take Samarkand, works like The Fortune Teller (1868) and Steamboat on the Volga (1893) are known to be or have been in private hands or smaller collections.

As a writer and ethnographer, he contributed to the Russian understanding of Central Asia and popularized travel and adventure literature. He helped shape the visual and literary culture of his time, bringing distant parts of the Empire closer to the Russian public.

Enduring Significance in Art History

Nikolai Nikolaevich Karazin's position in art history is secured by his unique role as a soldier-artist and ethnographic chronicler. He was not a revolutionary in terms of artistic style, but his dedication to documenting the world around him, particularly the expanding frontiers of the Russian Empire, gives his work lasting importance. He provided a visual narrative for an era of significant geopolitical change and cultural encounter.

His art offers a window into the mindset of 19th-century Russia, its imperial ambitions, its fascination with "the Orient," and its efforts to understand and incorporate diverse peoples into its fold. While modern perspectives may critique the colonial undertones inherent in some of this imperial art, Karazin's work remains an invaluable resource for historians, ethnographers, and art lovers alike, admired for its detail, its narrative power, and its vibrant depiction of a bygone era. He successfully bridged the gap between reportage and art, creating a body of work that continues to inform and fascinate.