Edward Lear stands as one of the most beloved and unique figures of the Victorian era, a multi-talented individual celebrated primarily as an artist, illustrator, author, and poet. Born on May 12, 1812, in Highgate, then a village just outside London, and passing away on January 29, 1888, in San Remo, Italy, Lear's life spanned a period of significant change in British society and culture. He is best known today for his delightful and enduring "nonsense" literature, particularly his popularization of the limerick form, and for iconic poems like "The Owl and the Pussy-Cat." However, his contributions to ornithological illustration and landscape painting were also substantial, revealing a complex artistic personality that navigated between meticulous observation, whimsical imagination, and profound melancholy. This exploration delves into the life, work, and legacy of Edward Lear, examining his artistic development, his literary achievements, his extensive travels, and his enduring place in both art and literary history.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Edward Lear's beginnings were somewhat unconventional. He was the twentieth child born to Jeremiah Lear, a stockbroker, and Ann Clark Skerrett. Due to the family's fluctuating financial fortunes and the sheer number of children, young Edward was placed under the primary care of his eldest sister, Ann, who was twenty-one years his senior. Ann became a surrogate mother, providing him with his early education and fostering his burgeoning talents. Lear did not receive a formal education in the traditional sense, a fact that perhaps contributed to his unconventional approach to both art and language later in life.

From a young age, Lear suffered from various health problems that would plague him throughout his life. He experienced epileptic seizures, which he referred to euphemistically as "the Morbids," starting around the age of six. He also battled chronic bronchitis and asthma, and periods of severe depression, which he termed "the Gloom." These conditions undoubtedly shaped his personality and his worldview, perhaps contributing to both the escapism found in his nonsense and the melancholic undertones present in some of his landscapes and writings. His later struggles with deteriorating eyesight would also significantly impact his artistic practice.

Despite these challenges, Lear displayed a precocious talent for drawing and painting. By the age of 15, he was already earning money by producing anatomical drawings for doctors and creating illustrations for natural history subjects. His skill in detailed observation and precise rendering quickly became apparent. This early work laid the foundation for his first major artistic endeavor: zoological illustration.

The Zoological Illustrator

Lear's exceptional talent for capturing the natural world with accuracy and artistry led him to seek employment as an ornithological draughtsman. Around 1830, he began working for the Zoological Society of London, producing drawings of birds at the Regent's Park Zoo. His skills were quickly recognized, and he was granted permission to draw the parrots in the Society's collection. This resulted in his first major publication, Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots, published in parts between 1830 and 1832.

This ambitious project, featuring large, hand-colored lithographs, was remarkable for several reasons. Lear was only eighteen when he began, yet the work displayed extraordinary technical skill and scientific accuracy. He depicted many species never before illustrated, drawing directly from live specimens rather than stuffed ones, which lent his images a vitality often missing in contemporary works. His parrot illustrations rivaled those of the great American naturalist John James Audubon, though Lear's focus was perhaps more on scientific representation than Audubon's dramatic compositions. Lear's work earned him favorable comparisons and established his reputation as a serious natural history artist. He also contributed illustrations to works by other prominent naturalists, including John Gould.

His success with the parrot book led to a significant commission from Lord Stanley, later the 13th Earl of Derby. Lord Stanley maintained an extensive private menagerie at his estate, Knowsley Hall, near Liverpool. From 1832 to 1837, Lear spent considerable time at Knowsley, meticulously documenting the diverse collection of birds and animals. This period was crucial for Lear, providing him with financial stability, artistic confidence, and a welcoming social environment.

Knowsley Hall and the Seeds of Nonsense

Life at Knowsley Hall was formative for Lear in ways that extended beyond zoological illustration. While his primary task was the scientific documentation of Lord Derby's collection, he found himself embraced by the Stanley family and their guests. He was often invited to dine with the family, a departure from the usual separation between employers and employees in aristocratic households. It was during his time interacting with the Earl's children and grandchildren that Lear began to unleash his playful, imaginative side.

To amuse the young residents of Knowsley, Lear started creating humorous verses accompanied by quirky, expressive drawings. These were often in the five-line limerick form, a structure he would master and popularize. The verses featured eccentric characters and absurd situations, drawn with a characteristic simplicity and energy that perfectly complemented the text. These playful creations were a stark contrast to the meticulous detail required for his ornithological work, offering an outlet for his innate sense of fun and absurdity.

This period saw the genesis of what would become his most famous literary contribution: nonsense. The limericks and drawings created for the Knowsley children formed the core of his first collection, A Book of Nonsense, initially published in 1846 under the pseudonym "Derry Down Derry." The book was an immediate success, tapping into a growing public appetite for humor and whimsy, particularly for children's entertainment. Lear's nonsense provided a delightful escape from the often rigid proprieties of Victorian society.

The Rise of Nonsense Literature

A Book of Nonsense marked Lear's public debut as a purveyor of absurdity. The book primarily consisted of limericks, each illustrated with Lear's distinctive, minimalist line drawings. The humor often derived from the incongruity between the verse and the image, or from the sheer silliness of the characters and their predicaments. Unlike the moralizing tone common in much Victorian children's literature, Lear's nonsense was purely for enjoyment, celebrating wordplay, sound, and imaginative freedom.

Lear later expanded his repertoire of nonsense beyond the limerick. His subsequent collections, such as Nonsense Songs, Stories, Botany, and Alphabets (1871), More Nonsense Pictures, Rhymes, Botany, etc. (1872), and Laughable Lyrics (1877), introduced longer narrative poems, fantastical stories, invented botanical specimens, and playful alphabets. These works contained some of his most enduring creations, including "The Owl and the Pussy-Cat," "The Jumblies," "The Dong with a Luminous Nose," and "The Pobble Who Has No Toes."

His nonsense is characterized by its musicality, inventive language, and blend of melancholy and joy. Lear coined numerous neologisms, some of which, like "runcible" (as in "runcible spoon"), have entered the English language, albeit with uncertain meaning. His poems often feature journeys to strange lands, peculiar creatures, and a sense of gentle longing or sadness beneath the surface humor. This emotional complexity distinguishes his work from simpler forms of comedy and resonates with both children and adults. His approach can be contrasted with the more structured, logical absurdity of Lewis Carroll, another giant of Victorian nonsense, whose work often relied on parody and mathematical puzzles, illustrated with meticulous detail by Sir John Tenniel. Lear's nonsense felt more organic, emotional, and visually integrated with his own spontaneous-seeming art.

A Life Devoted to Travel

Around 1837, Lear's career took a significant turn. Plagued by his recurring health issues and perhaps feeling constrained by the demands of precise scientific illustration, coupled with worsening eyesight that made such detailed work difficult, he decided to leave England and pursue landscape painting. This decision inaugurated a lifetime of travel, driven partly by the search for warmer climates beneficial to his health, partly by a restless spirit, and largely by the desire for new artistic subjects.

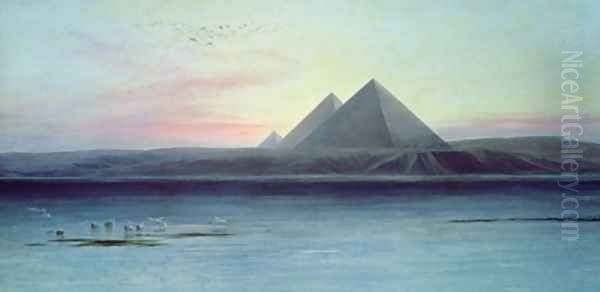

Italy became his first major destination and remained a central location throughout his life. He initially settled in Rome, immersing himself in the community of expatriate artists and exploring the city and its surrounding countryside, the Campagna. He later traveled extensively throughout the Italian peninsula, Sicily, and the Mediterranean islands, including Malta and Corfu, which became a particular favorite. His journeys took him further afield to Greece, Albania, Egypt (including voyages up the Nile), Palestine, Syria, Turkey, and, much later in life, a significant tour of India and Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka) in the 1870s.

These travels provided the raw material for his landscape art. Lear was a prolific sketcher, constantly recording his impressions in pencil and watercolor washes. He documented landscapes, architecture, local customs, and the effects of light and atmosphere. His travel journals, often illustrated and filled with witty observations, provide fascinating insights into his experiences and personality. He became a quintessential Victorian traveler, albeit one with a unique artistic and humorous perspective. His dedication to capturing foreign landscapes connects him to other traveling artists of the period, such as David Roberts, known for his views of the Near East, though Lear's style was generally looser and more focused on light and color.

Lear the Landscape Painter

As Lear transitioned from zoological illustration to landscape painting, his artistic style evolved. While his early landscapes retained a degree of topographical accuracy, influenced by his training in detailed observation, he became increasingly interested in capturing mood, atmosphere, and the dramatic effects of light and color. He worked primarily in watercolor outdoors, creating numerous sketches annotated with color notes ("remarkable rum," "intense purple," "dirty green"). Back in his studio, he would work these up into larger, more finished watercolors or oil paintings.

His landscape style is often characterized by strong compositions, bold contrasts of light and shadow, and a distinctive use of color, often featuring luminous skies and deep, resonant tones in the foreground. He was particularly drawn to the clear light and dramatic scenery of the Mediterranean and the Middle East. His paintings often evoke a sense of grandeur and solitude, sometimes tinged with the melancholy that was part of his temperament. Some critics have noted an affinity with the atmospheric effects in the work of J.M.W. Turner, the great master of English Romantic landscape painting, although Lear's approach was generally more grounded in specific locations.

Lear exhibited his landscapes regularly at the Royal Academy in London and sought recognition as a serious painter. He counted among his friends and acquaintances prominent artists like William Holman Hunt, a leading member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Lear accompanied Hunt on travels in the Middle East, and while Lear was never formally associated with the Pre-Raphaelites, his emphasis on truth to nature and detailed observation in his landscapes shows some shared sensibilities with painters like Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, particularly in their earlier work. However, Lear felt his landscape painting never achieved the critical or financial success he desired, often expressing frustration and self-doubt about his artistic standing compared to contemporaries like Lord Leighton or G.F. Watts, who represented the Victorian art establishment.

Despite his own reservations, Lear produced a vast body of landscape work that is highly regarded today for its skill, sensitivity, and unique perspective. His views of Italy, Greece, Egypt, and India capture not just the physical appearance of these places but also a sense of their history and atmosphere, filtered through his distinctive artistic vision. His dedication to depicting specific locales with both accuracy and feeling places him firmly within the tradition of British topographical painting, yet his handling of light and color pushes towards a more personal, expressive style.

Personal Life, Character, and Foss the Cat

Edward Lear's personal life was marked by both deep friendships and a sense of underlying loneliness. He never married, though he experienced strong emotional attachments, notably a complex and ultimately unfulfilled affection for Franklin Lushington, a young barrister he met in Malta. His closest relationships were often with men, and his letters reveal intense emotional bonds, leading to speculation about his sexuality, though definitive conclusions remain elusive within the context of Victorian social norms. He maintained long correspondences with friends like Lushington and Chichester Fortescue (later Lord Carlingford), which provide invaluable insights into his thoughts, feelings, and daily life.

His health remained a constant concern. The unpredictable nature of his epilepsy necessitated careful management of his social interactions and travel plans. He lived in fear of having a seizure in public and often structured his life to minimize this risk. His bouts of depression could be severe, leading to periods of isolation and creative block. Yet, despite these burdens, Lear possessed a remarkable capacity for humor, warmth, and friendship. He was known for his kindness, his love of children, and his witty conversation.

Perhaps Lear's most famous companion was his beloved cat, Foss, who lived with him for many years until the cat's death shortly before Lear's own. Foss was reportedly tailless (or had a very short tail) and featured in affectionate anecdotes and sketches by Lear. The deep bond between Lear and Foss highlights his capacity for affection and his need for companionship, often finding solace in the company of animals, a connection likely forged during his early years as a zoological illustrator. His self-portraits often humorously exaggerate his own features, particularly his prominent nose and spectacles, reflecting a self-deprecating wit.

In his later years, Lear settled permanently in San Remo on the Italian Riviera. He built a house, the Villa Tennyson, named in honor of his friend, the Poet Laureate Alfred, Lord Tennyson, whose poems Lear had set out to illustrate comprehensively – an ambitious project never fully completed. When a new hotel obstructed his view, Lear meticulously built an identical villa nearby, the Villa Tennyson II, ensuring his beloved outlook remained unchanged. He died there in January 1888, attended by a devoted manservant, his faithful cat Foss having predeceased him by only a few months.

Artistic and Literary Evaluation

Edward Lear occupies a unique position in cultural history, straddling the worlds of visual art and literature with remarkable success in both, though he is predominantly remembered for the latter. As an ornithological illustrator, his work, particularly the Psittacidae volume, is recognized for its scientific accuracy, technical brilliance, and aesthetic quality, placing him among the finest natural history artists of his time, comparable in skill, if not fame, to figures like Audubon and Gould.

As a landscape painter, Lear's reputation is more nuanced. While he produced thousands of accomplished works and was respected by fellow artists like Holman Hunt, he never quite achieved the widespread acclaim or financial rewards accorded to the leading landscape painters of the day, such as Turner or John Constable (though Constable belonged to an earlier generation). His style, while distinctive, perhaps fell between the established categories of topographical accuracy and high Romanticism. Today, his landscapes are appreciated for their strong sense of place, atmospheric effects, and skillful use of watercolor and oil, revealing a sensitive observer of the natural world. His own feelings of inadequacy regarding his painting career, however, persisted throughout his life.

It is in the realm of nonsense literature that Lear's genius is undisputed. He is widely regarded as the father of English nonsense verse, elevating the limerick to an art form and creating a body of work characterized by linguistic inventiveness, rhythmic vitality, imaginative freedom, and a unique blend of humor and pathos. His influence on children's literature has been profound and lasting, paving the way for later writers who embraced absurdity and playfulness. Figures like Lewis Carroll operated in a similar sphere, but Lear's integration of his own quirky drawings with his text created a unified artistic vision that remains distinctive. His work offered a necessary counterpoint to the didacticism prevalent in much Victorian writing for children, championed by illustrators like Kate Greenaway whose work, though charming, often reinforced conventional social values.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Edward Lear's legacy is multifaceted. His nonsense poems and limericks continue to delight readers of all ages, remaining staples of children's literature anthologies worldwide. "The Owl and the Pussy-Cat" is one of the most famous and beloved poems in the English language. His invented words and playful approach to language have subtly enriched English vocabulary and humor. The sheer joy and imaginative liberation found in his nonsense have influenced countless writers, poets, and artists. Some have even seen precursors to Surrealism in his illogical juxtapositions and dreamlike scenarios.

His contribution to natural history illustration remains significant, valued by both scientists and art collectors. His landscape paintings and drawings, once perhaps overshadowed by his literary fame, are increasingly recognized for their artistic merit and provide a rich visual record of his extensive travels during a period of burgeoning tourism and colonial expansion. His life of travel itself, undertaken despite significant personal challenges, can be seen as embodying a certain Victorian spirit of exploration and resilience.

Lear's ability to combine visual art and literature so seamlessly also sets him apart. Like the visionary artist and poet William Blake from an earlier generation, Lear created works where text and image are inextricably linked, each enhancing the other. While Lear's aims were vastly different from Blake's mystical explorations, both demonstrated the power of this dual medium. Edward Lear remains a cherished figure, celebrated for his boundless imagination, his gentle humor, his artistic skill, and the enduring magic of his nonsensical worlds. He offered laughter and escape, tinged with a recognizable human vulnerability, securing his place as a truly original voice in Victorian culture.

Conclusion

Edward Lear was far more than just the "Lord of Nonsense." He was a highly skilled and dedicated artist whose contributions spanned the detailed world of scientific illustration and the evocative realm of landscape painting. His life was one of constant movement, driven by health, art, and an insatiable curiosity about the world. Yet, it is his extraordinary gift for nonsense – for crafting verses and drawings that celebrate absurdity, sound, and pure imaginative play – that has cemented his lasting fame. Through his limericks, poems, and stories, Lear created unforgettable characters and fantastical journeys that continue to captivate and amuse. His unique blend of artistic talent, literary genius, humor, and melancholy makes him one of the most fascinating and enduring figures of the 19th century, a master whose work continues to resonate across generations.