Otto Franz Scholderer stands as a fascinating, if sometimes overlooked, figure in nineteenth-century European art. A German painter whose career bridged the late Romantic sensibilities of his early training with the burgeoning Realism and nascent Impressionism he encountered in Paris and London, Scholderer carved out a distinct niche for himself. His meticulous still lifes, insightful portraits, and early landscapes reveal an artist deeply engaged with the technical and philosophical shifts transforming the art world. His connections with prominent artists across Germany, France, and England further illuminate the interconnectedness of artistic movements during this dynamic period.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations in Frankfurt

Born on January 25, 1834, in Frankfurt am Main, Otto Franz Scholderer's artistic journey began in a city with a rich cultural heritage. In 1849, at the age of fifteen, he enrolled in the prestigious Städel Academy of Arts (Städelsches Kunstinstitut). This institution, founded by the banker and merchant Johann Friedrich Städel, was a vital center for artistic training in the German Confederation, fostering a range of styles but generally grounded in academic tradition.

During his formative years at the Städel, from 1849 to 1858, Scholderer studied under influential figures. Among his teachers was Johann David Passavant, a painter associated with the Nazarene movement but also a respected art historian. Passavant's scholarly approach likely instilled in Scholderer a deep appreciation for art history and meticulous observation. Another key instructor was Jakob Becker, a genre and landscape painter known for his detailed and often anecdotal scenes of rural life. Becker's influence might be seen in Scholderer's early inclination towards landscape painting.

The artistic environment in Frankfurt during Scholderer's youth was still largely influenced by the lingering currents of German Romanticism, with its emphasis on emotion, individualism, and the sublime beauty of nature. However, new artistic ideas were beginning to permeate from other European centers, particularly Paris. Scholderer's initial works, primarily landscapes, likely reflected this blend of traditional training and an awakening interest in more contemporary modes of expression.

Parisian Encounters and the Embrace of Realism

A pivotal moment in Scholderer's artistic development occurred with his visits to Paris. Between 1857 and 1858, he made several short study trips to the French capital, then the undisputed epicenter of the avant-garde. It was here that he forged connections that would profoundly shape his artistic trajectory.

In 1857, Scholderer met Henri Fantin-Latour, a French painter and lithographer who would become a lifelong friend and correspondent. Their friendship, documented through decades of letters, was remarkable, especially considering the often-strained political relations between France and Germany during this period. Fantin-Latour, known for his exquisite floral still lifes and group portraits of contemporary artists and writers (such as "Homage to Delacroix" and "A Studio at Les Batignolles"), moved in circles that included the most progressive artists of the day.

Through Fantin-Latour, Scholderer was introduced to the revolutionary art of Gustave Courbet. Courbet was the leading figure of the Realist movement, which rejected the idealized subjects of academic art and Romanticism in favor of depicting ordinary people and everyday life with unvarnished honesty. Courbet's bold technique and socially conscious subject matter, exemplified in works like "The Stone Breakers" and "A Burial at Ornans," were a revelation to many younger artists. Scholderer was undoubtedly impressed by Courbet's powerful naturalism and his commitment to painting what he saw.

During these Parisian sojourns, Scholderer also encountered Édouard Manet. Manet, a controversial and highly influential figure, was challenging artistic conventions with works that bridged Realism and the emerging Impressionist movement. His paintings, such as "Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe" and "Olympia," shocked the Parisian art establishment but signaled a new direction for modern art. The interactions with Fantin-Latour, Courbet, and Manet exposed Scholderer to the forefront of artistic innovation, pushing him away from purely Romantic or academic approaches and towards a more direct, observational style. This period marked a shift in his focus from landscapes towards still life and portraiture, genres where the principles of Realism could be intensely applied.

The Leibl Circle and German Realism

Upon returning to Germany, Scholderer did not remain isolated. He became associated with the "Leibl-Kreis" (Leibl Circle), a group of German artists centered around Wilhelm Leibl. Leibl, who had also spent time in Paris and admired Courbet, advocated for a form of Realism characterized by meticulous detail, sober palettes, and a focus on capturing the unadorned truth of the subject, often drawing inspiration from Old Masters like Hans Holbein the Younger and Dutch Golden Age painters.

The Leibl Circle included other significant German artists such as Wilhelm Trübner, known for his powerful portraits and landscapes that sometimes verged on Impressionism; Carl Schuch, a master of still life painting with a rich, dark palette; and Hans Thoma, whose work, while rooted in Realism, often incorporated more idyllic and symbolic elements. These artists shared a commitment to direct observation and a rejection of the prevailing academic historicism and sentimental genre painting.

Scholderer's involvement with the Leibl Circle solidified his commitment to Realist principles. His still lifes from this period demonstrate a keen eye for texture, light, and composition, rendered with a precision that aligns with the group's ethos. While Leibl himself often focused on peasant scenes and portraits, Scholderer found his primary expression of Realism in the intimate world of objects and the human face. The influence of Dutch masters like Willem Kalf or Pieter Claesz can be discerned in the careful arrangement and tactile rendering of his still lifes.

Another important friendship during his time in Germany was with Victor Müller, a history painter whom Scholderer met in Düsseldorf. Müller, like Scholderer, was open to modern French influences, particularly Courbet. This friendship likely provided further intellectual and artistic stimulus, reinforcing Scholderer's engagement with contemporary European art trends.

A New Chapter in London

In 1871, following the Franco-Prussian War and the establishment of the German Empire, Scholderer made a significant life change: he moved to London. He would reside in the British capital for the remainder of his life, until his death in 1902. The reasons for this move are not entirely clear, but London offered a large and diverse art market, and perhaps a degree of neutrality or distance from the continental political upheavals.

In London, Scholderer continued to develop his art, focusing primarily on still lifes and portraits. While described as living a somewhat reclusive life with limited contact with British painters, he was by no means isolated from the art world. He maintained his connections with continental artists, particularly his correspondence with Fantin-Latour. Fantin-Latour even provided Scholderer with instruction on pastel techniques via mail between 1884 and 1886, and gifted him a portrait.

Despite not achieving a major breakthrough or widespread fame, Scholderer's work found recognition among London critics. His paintings were exhibited, and his meticulous craftsmanship and refined sensibility were appreciated. The London art scene at this time was vibrant, with the Royal Academy maintaining its dominance, but also with challenges from figures like James Abbott McNeill Whistler, an American expatriate whose aestheticism and connections to French art mirrored some of Scholderer's own international outlook. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, with artists like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais, had earlier championed a different kind of detailed realism, though Scholderer's style was more aligned with continental Realism.

His time in London saw the continued production of sophisticated still lifes. These works often featured carefully arranged objects – fruit, flowers, glassware, and porcelain – rendered with a palpable sense of texture and a subtle interplay of light and shadow. His portraits, too, were characterized by their psychological insight and sober, yet elegant, execution.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Otto Franz Scholderer's artistic style is best characterized as a nuanced blend of Realism with lingering Romantic undertones and an awareness of Impressionistic techniques, particularly in his handling of light. He was not a radical innovator in the vein of Monet or Cézanne, but rather a master craftsman who absorbed contemporary influences into a distinctive personal idiom.

Still Lifes: The Core of His Oeuvre

Still life painting was central to Scholderer's artistic output, especially in his mature period. His approach to the genre was marked by meticulous observation, a refined sense of composition, and a love for the material qualities of objects. He often chose everyday items, but arranged them with an eye for harmony and balance, transforming the mundane into subjects of quiet contemplation.

One of his notable still lifes is "Lilac" (c. 1860-1902), now in the collection of the National Gallery, London. This work showcases his ability to capture the delicate texture of petals and the subtle gradations of color, all set against a dark, atmospheric background that allows the flowers to emerge with luminous clarity. The influence of Dutch Golden Age still life painters is evident, but Scholderer's handling often has a slightly softer, more atmospheric quality.

Another intriguing work is "The Masqueraders - Before the Ball." While primarily a still life featuring masks, musical instruments, and other accoutrements of a masquerade, it hints at a narrative or symbolic meaning that remains somewhat enigmatic. This painting demonstrates his skill in creating complex arrangements and his interest in objects that evoke a sense of occasion or hidden stories. His still lifes often possess a quiet dignity and a sense of timelessness. He explored the interplay of textures – the gleam of silver, the transparency of glass, the bloom on fruit – with consummate skill.

Portraits: Capturing Character

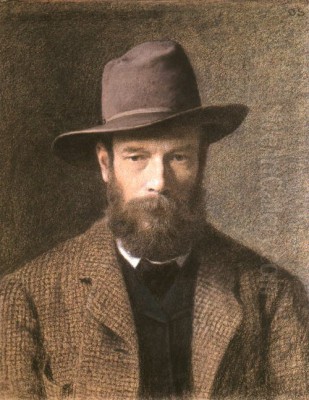

Scholderer was also an accomplished portraitist. His portraits are generally characterized by their straightforwardness and psychological acuity. He avoided flattery, seeking instead to capture the essential character of his sitters. The "Portrait of the Artist's Wife" is a fine example, revealing a sensitive and intimate portrayal. His portraits often feature a subdued palette and a focus on the face and hands, rendered with careful attention to detail. He was adept at conveying a sense of presence and individuality, aligning with the Realist emphasis on truthful representation. Other German portraitists of the era, like Franz von Lenbach or Wilhelm Leibl himself, also excelled in this genre, each with their distinct approach.

Landscapes: Early Explorations

Though he later concentrated on still life and portraiture, Scholderer's early career included a focus on landscape painting. Works like "Der Geiger am Fenster" (The Violinist at the Window), likely from his earlier period, show his engagement with this genre. These landscapes probably reflected the influence of his teacher Jakob Becker and the prevailing Romantic interest in nature, possibly combined with an emerging Realist desire to depict specific locales with accuracy. While fewer of his landscapes are as well-known as his still lifes, they form an important part of his artistic development, showing his initial grounding before his encounters with the French avant-garde.

A Transitional Figure

Scholderer's art reflects the transition from the idealism of Romanticism to the objective observation of Realism, with an awareness of the Impressionists' concern for light and color. He did not fully embrace the broken brushwork or en plein air methods of Impressionists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, or Alfred Sisley. Instead, his work retained a more solid, traditional structure, but often infused with a sensitivity to atmospheric effects that suggests an understanding of Impressionist principles. His careful, almost reverent, depiction of objects in his still lifes connects him to a long tradition, from Chardin to Fantin-Latour, while his portraits share the sober honesty of many Realist painters.

Key Relationships and Enduring Friendships

The friendships Scholderer cultivated were crucial to his artistic life. His long-standing bond with Henri Fantin-Latour was perhaps the most significant. Their correspondence, spanning over four decades, provided a vital link to the Parisian art world, even after Scholderer moved to London. This exchange of ideas, critiques, and personal news sustained both artists. Fantin-Latour's own dedication to still life and portraiture, alongside his connections to the Impressionist circle (though he himself was not strictly an Impressionist), provided a constant point of reference for Scholderer.

His encounters with Édouard Manet and Gustave Courbet in Paris were transformative. While these may not have developed into the same kind of intimate, long-term friendship as with Fantin-Latour, their artistic impact was undeniable. Courbet's robust Realism provided a powerful alternative to academic art, while Manet's daring modernism opened up new possibilities for subject matter and technique.

Within Germany, his association with the Leibl Circle placed him among the leading proponents of German Realism. The shared ideals and mutual support within this group, which included Wilhelm Leibl, Wilhelm Trübner, Carl Schuch, and Hans Thoma, were important for reinforcing his artistic direction. These artists, while diverse in their individual expressions, collectively sought an authentic, unembellished representation of reality, often looking to artists like Holbein or the Dutch Masters for inspiration, as well as to Courbet.

The German art scene also included figures like Adolph Menzel, an older master of Realism whose meticulous observation and historical scenes were highly influential, and later, the German Impressionists like Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth, and Max Slevogt, who took German art in new directions towards the end of Scholderer's life. While Scholderer's path was distinct, he was part of this broader evolution of German art in the 19th century.

Later Years and Legacy

Otto Franz Scholderer spent the last three decades of his life in London, continuing to paint and exhibit. Although he did not achieve the same level of fame as some of his French contemporaries or even some members of the Leibl Circle, he maintained a respected position as a skilled and thoughtful artist. His dedication to his craft was unwavering.

In his later years, he eventually returned to his birthplace, Frankfurt am Main. He passed away there on January 22, 1902, just three days shy of his 68th birthday. His son, Julius Franz Scholderer, went on to become a distinguished bibliographer and incunabulist, notably working at the British Museum.

Otto Franz Scholderer's legacy lies in his contribution to the Realist movement, particularly in Germany, and in his role as a conduit for artistic ideas between continental Europe and Britain. His still lifes are perhaps his most enduring achievement, admired for their technical mastery, subtle beauty, and quiet intensity. They represent a significant contribution to the genre in the 19th century, holding their own alongside the works of contemporaries like Fantin-Latour.

His work is represented in several public collections, including the Städel Museum in Frankfurt, the National Gallery in London, and other museums in Germany and elsewhere. While he may not be a household name, art historians and connoisseurs recognize his skill and the unique position he occupied, navigating the complex artistic currents of his time with integrity and a distinctive personal vision. He remains a testament to the rich diversity of 19th-century European painting, an artist whose meticulous eye and steady hand captured the tangible beauty of the world around him.

Conclusion: A Quiet Master of Observation

Otto Franz Scholderer's career exemplifies the journey of an artist deeply engaged with the traditions of painting yet responsive to the transformative artistic ideas of the 19th century. From his academic training in Frankfurt to his pivotal encounters with the Parisian avant-garde and his mature years in London, he consistently pursued a path of meticulous observation and refined craftsmanship. As a member of the Leibl Circle, he contributed to the development of German Realism, while his enduring friendship with Fantin-Latour kept him connected to the pulse of French art.

His still lifes, in particular, stand out for their exquisite detail, subtle handling of light, and profound appreciation for the material world. His portraits capture the character of his sitters with honesty and sensitivity. Though perhaps not a revolutionary, Scholderer was a dedicated and highly skilled painter whose work reflects a thoughtful synthesis of influences, resulting in an art that is both historically significant and aesthetically rewarding. He remains an important figure for understanding the cross-currents of European art in an era of profound change, a quiet master whose dedication to his art continues to resonate.