Richard Lorenz (1858-1915) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the annals of American art, particularly renowned for his depictions of the American West and his mastery in portraying horses. Born in Germany and trained in its rigorous academic traditions, Lorenz brought a European sensibility to the raw, burgeoning narratives of the American frontier. His career spanned the popular phenomenon of panoramic painting to the more intimate scale of easel works, and he played a vital role as an educator and organizer in the American Midwest's burgeoning art scene.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations in Germany

Richard Lorenz was born on February 9, 1858, in Voigtstedt, a village in the Thuringian region of Germany, an area rich in cultural and artistic heritage. His early aptitude for art led him to pursue formal training, a path that would deeply shape his technical skills and aesthetic outlook. He enrolled at the prestigious Weimar Saxon-Grand Ducal Art School (Großherzoglich-Sächsische Kunstschule Weimar). This institution was a crucible of artistic thought, having been associated with figures like Friedrich Preller the Elder and later, under the directorship of Stanislaus von Kalckreuth, it fostered a strong tradition of landscape and figure painting.

At Weimar, Lorenz had the distinct advantage of studying under Professor Theodor Hagen (1842-1919). Hagen was a prominent German landscape painter, himself a student of Oswald Achenbach, and a leading figure in the German Impressionist movement, though his teaching often emphasized solid academic grounding. Under Hagen's tutelage, Lorenz would have been immersed in the principles of precise draughtsmanship, anatomical accuracy, and the nuanced observation of light and color, particularly in landscape and animal studies. This training was crucial, especially for his later specialization in equine subjects. The Weimar school, during this period, was also a place where artists like Max Liebermann and Lovis Corinth, who would become giants of German art, were developing, though their paths would diverge more strongly towards Impressionism and Expressionism respectively. Lorenz's foundation, however, remained rooted in a more realistic, albeit often romanticized, depiction.

His talent was recognized early. In 1886, Lorenz received the Carl Alexander Prize, a significant commendation from the Weimar school, which not only validated his skills but also likely opened doors for future opportunities. This academic success marked the culmination of his German training and set the stage for a dramatic shift in his life and artistic focus.

The American Panorama Venture and Emigration

The late 19th century witnessed a surge in the popularity of panoramic paintings, enormous, immersive artworks that offered audiences a 360-degree view of historical events, famous battles, or exotic landscapes. These were the cinematic experiences of their day. It was this burgeoning industry that drew Richard Lorenz to the United States. William Wehner, an entrepreneur and head of the American Panorama Company, was actively recruiting talented European artists, particularly Germans, known for their technical proficiency, to work on these large-scale projects.

Following his award, Lorenz was hired by Wehner and, in 1886, he emigrated to America, settling in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, which had become a major center for panorama production. He joined a team of artists, many of whom were fellow Germans, such as Friedrich Wilhelm Heine, August Lohr, Hermann Michalowski, and Franz Roubaud (though Roubaud was more active in Europe, his style was similar to that of panorama painters). This collaborative environment was intense; artists often specialized, with some focusing on landscapes, others on figures, and some, like Lorenz, excelling in depicting animals, particularly horses in dynamic action.

Working for the American Panorama Company, Lorenz contributed to several monumental works. Among the most notable were "The Battle of Atlanta" and "Jerusalem on the Day of the Crucifixion." These paintings were massive undertakings, requiring meticulous research, historical accuracy (or at least a convincing semblance of it), and the ability to create a compelling, illusionistic space. Lorenz's skill in rendering horses with anatomical precision and a sense of vitality was invaluable for battle scenes, making the charging cavalry and artillery teams come alive. This period honed his ability to manage complex compositions and depict dramatic narratives on a grand scale. Other panorama painters active in America or Europe around this time, whose work shared some characteristics, included Paul Philippoteaux, famous for his Gettysburg cyclorama, and Édouard Detaille, a French master of military scenes.

Transition to Western Themes and Easel Painting

While the panorama boom provided steady work, its popularity began to wane by the late 1880s and early 1890s with the advent of newer forms of entertainment. This shift prompted Lorenz, like many of his colleagues, to turn towards easel painting. It was during this transitional period that Lorenz found his most enduring subject matter: the American West.

Between 1887 and 1888, Lorenz undertook extensive travels across the American West, journeying through California, Texas, Colorado, Oregon, and Arizona. These expeditions were not mere sightseeing tours; they were immersive experiences that provided him with firsthand observations of the landscapes, the people, and the unique atmosphere of the frontier. He sketched prolifically, capturing the vast plains, rugged mountains, the daily lives of cowboys, Native American communities, and the ubiquitous horses and cattle that were central to the Western experience.

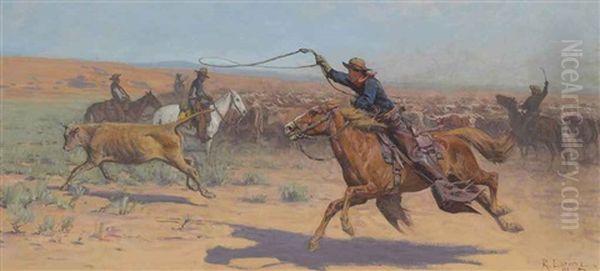

This direct engagement with the West transformed his art. While his European academic training provided a strong technical foundation, the subjects were now distinctly American. He began to produce oil paintings that captured the drama and romance of the West, often focusing on scenes of cowboy life, cattle drives, and encounters on the plains. His deep understanding of equine anatomy, honed during his academic studies and panorama work, made his depictions of horses particularly compelling and sought after.

One of his most famous easel paintings from this period is "Burial on the Plains" (also known as "The Last Rites"). This poignant work, now housed in the collection of the Denver Art Museum, depicts a solemn moment as a group of cowboys lays a comrade to rest under the vast, indifferent sky of the prairie. The painting showcases Lorenz's ability to convey emotion, his skilled rendering of figures and animals, and his sensitivity to the Western landscape. It stands as a testament to his successful transition from the grand spectacle of panoramas to the more personal expression of easel art.

Artistic Style: European Realism Meets American Frontier

Richard Lorenz's artistic style is a fascinating blend of his German academic training and his adopted American subject matter. He is often compared to other prominent artists of the American West, most notably Frederic Remington (1861-1909) and Charles M. Russell (1864-1926). While Remington was known for his dramatic, often action-packed illustrations and bronzes, and Russell for his narrative, anecdotally rich depictions of cowboy life, Lorenz brought a slightly different, perhaps more painterly and atmospheric quality, rooted in European traditions.

His draughtsmanship was impeccable, a direct result of his Weimar education. This precision is evident in the anatomical accuracy of his figures and, especially, his horses. Lorenz was a master animalier, capturing not just the physical form of the horse but also its spirit, movement, and character. Whether depicting a cavalry charge, a team pulling a wagon, or a cowboy's trusted mount, his horses are always convincing and full of life. This skill set him apart and earned him the moniker "the horse painter." Charles Schreyvogel (1861-1912), another contemporary known for his dynamic portrayals of cavalry and Native American encounters, shared this focus on dramatic equine action.

Lorenz's landscapes, while often serving as backdrops to human or animal activity, were rendered with a keen eye for atmospheric effects. He captured the quality of light on the plains, the vastness of the Western sky, and the subtle colorations of the arid terrain. There's a certain romanticism in his work, a sense of nostalgia for a rapidly changing frontier, but it is generally tempered by a commitment to realistic detail. Unlike the earlier generation of Western artists like Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) or Thomas Moran (1837-1926), whose landscapes often emphasized sublime grandeur, Lorenz's focus was more on the human and animal narratives within the Western environment.

His palette could range from the dusty, muted tones of the plains to more vibrant hues when depicting dramatic sunrises or sunsets. His compositions were carefully constructed, reflecting his academic training, yet they often conveyed a sense of immediacy and action. He was less of an illustrator than Remington in his easel work, focusing more on the painterly qualities of the medium.

A Respected Educator and Community Leader in Milwaukee

Beyond his own artistic production, Richard Lorenz made significant contributions to the art community in Milwaukee as an educator and organizer. After the decline of the panorama industry, he established himself as a respected teacher. He taught drawing, painting, and sculpture at the Wisconsin School of Design, which later became the Wisconsin Art Institute. In this capacity, he influenced a generation of artists in the region.

His students included individuals who would go on to make their own marks in various artistic fields. For instance, Alexander Mueller, who became a notable painter and educator himself, studied under Lorenz. Perhaps more surprisingly, Edward Steichen (1879-1973), who would become one of the most important figures in the history of photography, initially studied drawing and painting with Lorenz before shifting his primary focus. This indicates the breadth of Lorenz's teaching and his ability to impart fundamental artistic principles. Gustave Moeller was another student who gained recognition.

Lorenz's commitment to fostering an artistic community extended to his involvement in art societies. In 1900, he was a key figure in founding the Society of Milwaukee Artists, serving as its first vice-president. This organization played a crucial role in promoting local artists and organizing exhibitions. It later evolved into the Wisconsin Painters & Sculptors, a testament to its enduring legacy. Lorenz was also a member of the Society of Western Artists, a broader organization that brought together painters and sculptors focused on Western themes, further connecting him with contemporaries like Henry Farny (1847-1916) who also specialized in depicting Native American life and Western scenes.

His studio in Milwaukee became a hub for artists, and he was known for his dedication to his students and his passion for art. He continued to paint and teach, dividing his time between his own creative pursuits and his educational responsibilities.

Later Career, Notable Works, and Legacy

In his later career, Richard Lorenz continued to produce Western-themed paintings, though he also undertook other commissions. His reputation as a skilled painter, particularly of horses, ensured a steady demand for his work. He also worked for a period in Chicago with the firm Reed & Gross, where he reportedly painted a panorama of the Great Chicago Fire, demonstrating his continued connection to large-scale, dramatic historical depictions.

His most celebrated easel painting remains "Burial on the Plains," which encapsulates his mature style and thematic concerns. Other works, though perhaps less widely known today, consistently demonstrate his technical skill and his affinity for Western subjects. These include scenes of Native American life, cowboys at work, and dramatic encounters on the frontier. His paintings often featured a strong narrative element, inviting viewers to imagine the stories behind the depicted scenes.

Richard Lorenz passed away in Milwaukee on August 4, 1915, at the age of 57. His death marked the loss of a significant artist who had successfully bridged two distinct artistic worlds: the academic traditions of 19th-century Europe and the vibrant, evolving subject matter of the American West.

His legacy is multifaceted. As a panorama painter, he contributed to a popular art form that captivated audiences in its time. As an easel painter, he created enduring images of the American West, contributing to the visual iconography of the frontier alongside more famous names like Remington and Russell. His particular strength in depicting horses earned him a special place among Western artists. Furthermore, his role as an educator and a founder of art institutions in Milwaukee had a lasting impact on the artistic development of the region. Artists like Carl von Marr, a German-American contemporary also active in Milwaukee and Munich, would have been part of this broader artistic milieu.

Collections and Auction Records

Today, Richard Lorenz's works are held in various public and private collections. The Denver Art Museum, as mentioned, holds his significant painting "Burial on the Plains." His works occasionally appear at auction, where they command respectable prices, reflecting a continued appreciation for his skill and his contribution to Western art.

For instance, a major work by Lorenz was reported to have sold for $280,000 at a Coeur d'Alene Art Auction, a premier venue for Western American art. This indicates a strong market recognition for his top-tier pieces. In another instance, seven of his large murals were sold at a Bonhams auction in December 2008 for over $35,000, showcasing the value placed on his larger-scale decorative works as well. These auction results underscore his status as a collectible and historically important artist of the American West. While the provided information also mentions collections in Vienna, Salamanca, and Moscow, and a personal collection including works by Atget and Brancusi, these references likely pertain to a different individual named Richard Lorenz, as the Western artist's primary sphere of activity and collection focus would align more with American institutions and Western art.

Conclusion: A Unique Voice in American Western Art

Richard Lorenz's journey from the art academies of Weimar, Germany, to the ranches and plains of the American West is a compelling story of artistic adaptation and dedication. He brought the rigorous discipline of European academic painting to the untamed subjects of the American frontier, creating a body of work characterized by technical proficiency, particularly in his masterful depictions of horses, and a romantic yet realistic portrayal of Western life.

While perhaps not as widely household a name as Remington or Russell, Lorenz carved out a distinct niche. He was more than just a "horse painter"; he was a skilled narrator of the Western experience, an important contributor to the panorama phenomenon, and a vital force in the cultural life of Milwaukee. His paintings offer a window into a pivotal period of American history, rendered with the eye of a European-trained master and the heart of an artist captivated by the spirit of the West. His influence extended through his teaching, shaping future artists and contributing to the growth of a vibrant art scene in the American Midwest. Richard Lorenz remains a significant figure whose work continues to be appreciated for its artistic merit and its historical resonance. His legacy is preserved in the collections that house his art and in the ongoing story of American Western painting, a genre he significantly enriched.