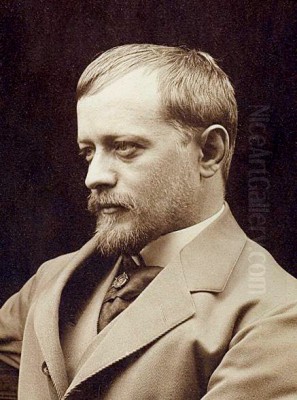

Otto Greiner stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in German art at the turn of the 20th century. A master draftsman, printmaker, and painter, Greiner carved a unique niche for himself, blending meticulous classical technique with the burgeoning ideals of Symbolism. His life, though tragically cut short, was one of intense artistic dedication, deeply influenced by his admiration for his contemporary Max Klinger and his profound love for Italy, which became his adopted home. His works, often monumental in scale and ambition, explored grand mythological themes, the human form, and the power of graphic expression, leaving a legacy that continues to intrigue art historians and enthusiasts alike.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Germany

Born in Leipzig on December 16, 1869, Otto Greiner's artistic journey began in his hometown, a significant center for publishing and graphic arts in Germany. This environment undoubtedly played a role in his early inclination towards printmaking. He initially apprenticed as a lithographer and etcher, gaining foundational skills that would serve him throughout his career. His talent was evident early on, and in 1888, he received a scholarship that enabled him to further his studies at the prestigious Munich Academy of Art.

Munich, at this time, was a vibrant artistic hub, rivaling Berlin and Paris in its dynamism. It was here that Greiner encountered the work and, eventually, the person of Max Klinger (1857-1920). Klinger, already an established and highly influential artist, was a leading figure in German Symbolism, renowned for his powerful etchings, paintings, and sculptures that delved into psychological and philosophical themes. A meeting at a Munich exhibition where Klinger's works were displayed proved to be a pivotal moment for the young Greiner. Klinger's artistic vision, his technical mastery, and his intellectual depth left an indelible mark on Greiner, shaping his artistic aspirations and direction.

The influence of Klinger cannot be overstated. Klinger's own work often combined a precise, almost academic rendering of form with fantastical or allegorical subject matter, a path that Greiner would also follow. Artists like Franz von Stuck (1863-1928), another dominant figure in Munich Symbolism and a co-founder of the Munich Secession, also contributed to the city's rich artistic atmosphere, exploring mythological and allegorical themes with a distinctive, often sensuous style. While Greiner developed his own voice, the impact of these powerful Munich figures, especially Klinger, was formative.

The Italian Sojourn and the Klinger Connection

The allure of Italy, with its classical heritage and sun-drenched landscapes, has long captivated German artists, creating a tradition known as the "Deutschrömer" (German Romans). Greiner was no exception. In 1891, he traveled to Rome, where he reconnected with Max Klinger. This meeting solidified a deep and lasting friendship between the two artists. Klinger, who himself spent considerable time working in Italy, encouraged Greiner in his artistic pursuits.

For Greiner, Rome became more than just a place to study ancient art; it became his spiritual and artistic home. He immersed himself in the city's atmosphere, its classical ruins, and its vibrant contemporary art scene, which included a significant community of expatriate German artists. He found the environment conducive to his creative temperament, which leaned towards grand themes and the idealized human form, often set against Italianate backdrops.

In 1898, Greiner made the decisive move to settle permanently in Rome. He even took up residence in a studio near one previously occupied by Klinger, a testament to their close bond. He remained in Rome until 1915, when the outbreak of World War I and Italy's entry into the conflict on the side of the Allies forced him, as a German national, to return to Germany. This Roman period was arguably the most productive and defining of his career. He was highly regarded within the German artistic community in Rome, and his work from this era reflects a mature and confident artist grappling with complex compositions and profound themes.

The influence of Italian art, both classical and Renaissance, is palpable in Greiner's work. The clarity of form, the emphasis on anatomical precision, and the grandeur of conception echo the masters of the Italian tradition. He was not alone in this; artists like Arnold Böcklin (1827-1901), a Swiss-German Symbolist who also spent much of his career in Italy, similarly drew inspiration from the Mediterranean world for his evocative, often melancholic, mythological landscapes. Hans von Marées (1837-1887) and Anselm Feuerbach (1829-1880) were earlier "Deutschrömer" whose classical idealism also resonated within this tradition.

Artistic Style: Symbolism, Classicism, and the Nude

Otto Greiner's artistic style is a fascinating amalgamation of late 19th-century academic classicism and the more introspective, often enigmatic, currents of Symbolism. He possessed an extraordinary technical facility, particularly in drawing, which formed the bedrock of his art. His line was precise, controlled, and capable of rendering the human anatomy with remarkable accuracy and sensitivity.

Symbolism, as a movement, sought to express ideas and emotions not through direct representation but through suggestion, allegory, and symbolic imagery. Greiner embraced this approach, particularly in his choice of mythological subjects. These ancient tales provided him with a framework to explore universal human experiences, psychological states, and philosophical concepts. Unlike some Symbolists who veered towards the obscure or the decadent, Greiner's symbolism was often more direct, rooted in the narrative power of the myths themselves, yet imbued with a personal interpretation.

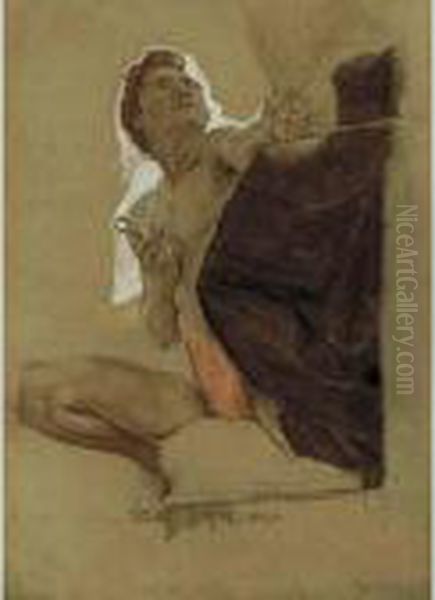

A central motif in Greiner's oeuvre is the nude human figure. He depicted nudes, both male and female, with a combination of classical idealization and realistic observation. These figures are rarely passive; they are often dynamic, engaged in dramatic action, or conveying intense emotion. His nudes are not merely academic studies but are integral to the narrative and symbolic content of his works. They are often set within meticulously rendered Italian landscapes, the specificity of the location grounding the mythological scenes in a tangible reality. This juxtaposition of the ideal and the real is a hallmark of his style.

His approach to composition was ambitious. He favored large-scale formats, whether in painting or printmaking, and populated them with multiple figures in complex arrangements. This monumental quality lent a sense of gravitas to his mythological scenes. His contemporary, Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) in Vienna, though stylistically different with his ornate patterns and decorative surfaces, also explored Symbolist themes and the female form with a similar intensity and often on a grand scale.

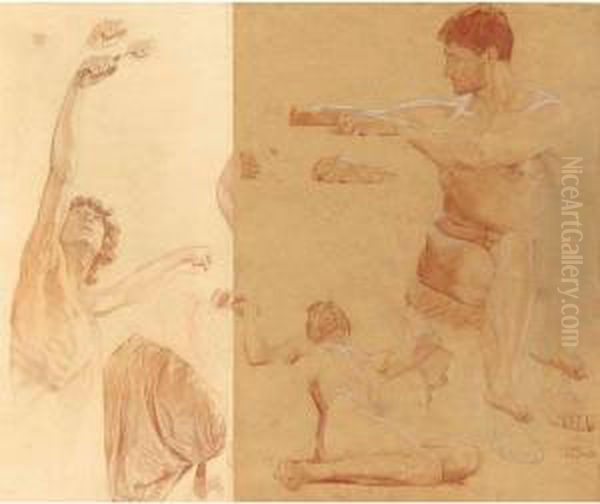

Master of the Graphic Arts: Prints and Drawings

While Greiner produced significant paintings, his reputation as a master perhaps rests most firmly on his achievements in the graphic arts – his drawings and prints. He was a prolific draftsman, producing a vast number of studies in various media, including ink, charcoal, red chalk (sanguine), colored pencils, and watercolor. These drawings were not merely preparatory sketches but were often highly finished works in their own right, showcasing his exquisite control of line, his understanding of anatomy, and his ability to model form through subtle gradations of tone.

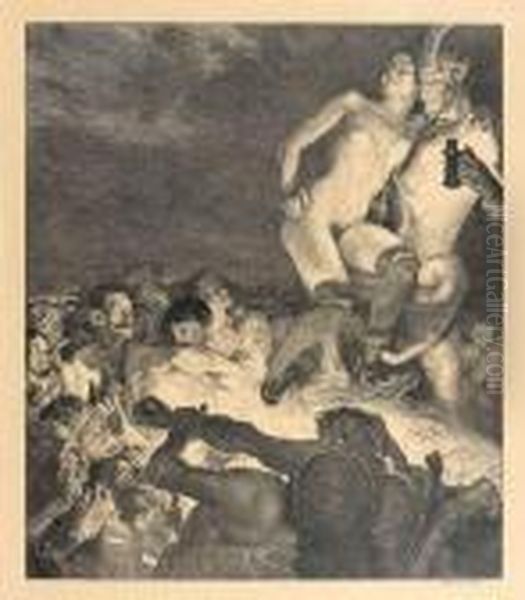

His printmaking, particularly his lithographs and etchings, allowed him to explore complex compositions and disseminate his work to a wider audience. Max Klinger was a towering figure in German printmaking, and Greiner clearly learned much from his example, particularly in terms of creating ambitious, multi-plate print cycles. Greiner's prints are characterized by their technical brilliance, their rich tonal variations, and their powerful imagery.

One of his notable print series is Vom Weib (Of Woman), which explores various facets of womanhood, often through allegorical or symbolic representations. A specific print from this series, Der Mörser (The Mortarman or The Grinder), exemplifies his ability to imbue a seemingly simple scene with deeper meaning, focusing on the physicality and intensity of the figure. His graphic works often possess a dramatic power and a psychological depth that is compelling. In this dedication to the graphic arts, he shared a common ground with artists like Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945), a contemporary German artist whose powerful prints, though focused on social realism and human suffering, demonstrated a similar mastery of line and emotional intensity. Edvard Munch (1863-1944), the Norwegian Symbolist, also heavily relied on printmaking to convey his deeply personal and emotionally charged themes.

Monumental Visions: Key Masterpieces

Otto Greiner's ambition was often expressed in large, complex compositions that tackled significant mythological or allegorical subjects. These works required meticulous planning and execution, often involving numerous preparatory studies.

Odysseus and the Sirens: This painting, now housed in the Museum der bildenden Künste in Leipzig, is one of his most famous works. It depicts the dramatic moment from Homer's Odyssey where Odysseus, tied to the mast of his ship, resists the enchanting song of the Sirens. Greiner captures the tension and allure of the scene, with the powerful male nudes of Odysseus's crew straining at their oars, their ears plugged with wax, while the seductive Sirens attempt to lure them to their doom. The composition is dynamic, the figures rendered with anatomical precision, and the Italian coastal setting vividly portrayed.

Prometheus: Held in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada in Toronto, this work tackles another potent Greek myth. Prometheus, the Titan who stole fire for humanity, is shown chained to a rock, enduring his eternal punishment. Greiner's depiction emphasizes the heroic suffering and defiance of Prometheus, his muscular form contorted in agony yet retaining a sense of indomitable spirit. It is a powerful exploration of themes of rebellion, sacrifice, and the human condition.

Hercules Cycle: Greiner was drawn to the figure of Hercules, the epitome of strength and heroic endeavor. He created several works featuring the hero, including Hercules and Omphale (Staatsgalerie Stuttgart), which depicts the hero in servitude to the Lydian queen, a theme exploring the subversion of power and gender roles. Other Hercules subjects, such as Hercules with Eupam or Hercules and the Cattle, further demonstrate his fascination with this mythological figure, allowing him to explore dynamic compositions and the male nude in heroic action.

Gaia (Gea): This subject, representing the primordial Earth goddess, was one Greiner returned to, particularly in his graphic work. His lithograph Gea is considered one of his most significant and labor-intensive prints. It typically depicts a monumental female nude, embodying the fecundity and power of nature, often surrounded by smaller figures or symbolic elements. This work showcases his mastery of lithography and his ability to create images of iconic power.

These major works, along with numerous others, reveal Greiner's commitment to a form of "idealistic realism," where meticulously observed reality was placed in the service of grand, symbolic narratives. His approach can be contrasted with the emerging modernist movements of his time, such as the burgeoning Expressionism in Germany with groups like Die Brücke (founded 1905) or the contemporary experiments of French artists like Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) in sculpture, who, while also focused on the human form, pushed towards greater emotional expression and formal abstraction. Greiner, however, remained more firmly rooted in a tradition that valued classical form and narrative clarity, albeit infused with Symbolist sensibility.

Greiner and His Contemporaries: A Wider Circle

Beyond the profound influence of Max Klinger, Otto Greiner operated within a rich network of artistic exchange and influence. In Rome, he was part of a vibrant German-speaking artistic community. While he developed a distinct personal style, he was aware of broader European artistic trends.

The Italian art scene itself was undergoing transformations. Artists like Giovanni Segantini (1858-1899), an Italian Symbolist known for his Alpine landscapes and allegorical figures, or Gaetano Previati (1852-1920), a key figure in Italian Divisionism with Symbolist leanings, were his contemporaries. Later, the rise of Italian Futurism, spearheaded by artists like Umberto Boccioni (1882-1916), who mentioned Greiner in his writings as a notable figure in the Roman art scene, represented a radical break from the classical and Symbolist traditions Greiner cherished.

In Germany, the artistic landscape was diverse. Max Liebermann (1847-1935), a leading figure in German Impressionism and later president of the Prussian Academy of Arts, represented a more naturalistic and modern approach. Lovis Corinth (1858-1925), initially associated with naturalism and Impressionism, later developed a more expressive, powerful style that bordered on Expressionism, often tackling mythological and biblical scenes with a raw energy quite different from Greiner's polished classicism. Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876-1907), one of the most important early Expressionists, was forging a radically different path with her simplified forms and emotionally direct portraits and nudes.

Greiner's commitment to the human figure and mythological themes placed him somewhat apart from the avant-garde movements that were gaining momentum. Yet, his work shared with Symbolism a desire to look beyond surface appearances to explore deeper meanings and psychological states. His emphasis on technical skill and monumental composition aligned him with a tradition of "grand manner" art, which, while perhaps falling out of favor with the most radical modernists, still held considerable prestige.

Social Engagement, Later Years, and Untimely Death

Otto Greiner was not solely confined to his studio. He engaged with the art world in practical ways. For instance, he collaborated with Paul Hartmann in organizing auctions that featured not only fine art but also decorative arts, furniture, and textiles, indicating an interest in the broader material culture and the art market. He also undertook illustration work, notably creating lithographs for Eduard Fuchs's Die Geschichte der erotischen Künste (The History of Erotic Arts), a project that aligned with his interest in the human form and, at times, more sensual themes.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914, and Italy's subsequent entry into the war against the Central Powers in 1915, brought a dramatic end to Greiner's long and fruitful Roman sojourn. As a German citizen, he was compelled to leave his adopted home and return to Germany. He settled in Munich, the city where his artistic journey had truly begun to flourish.

Even amidst the turmoil of war, Greiner's artistic ambitions remained undiminished. He embarked on a major project: a large-scale mural decoration. This undertaking, however, was destined to remain unfinished. Otto Greiner contracted pneumonia and died in Munich on May 24, 1916, at the relatively young age of 46. His premature death cut short a career that, while already substantial, still held considerable promise.

Legacy and Posthumous Recognition

Otto Greiner's death during the war meant that his legacy took time to be fully assessed. Some of his works, particularly those left unsigned, were later authenticated by his widow, Nannina Greiner, after the war. His oeuvre, though not as widely known today as that of some of his more revolutionary contemporaries, holds a significant place in the history of German Symbolism and figurative art.

His mastery of drawing and printmaking remains undisputed. His works are held in numerous public collections in Germany, Canada, and elsewhere, attesting to their enduring quality. Art historians recognize him as a key disciple of Max Klinger, yet also as an artist who developed his own powerful and distinctive vision. He represents a fascinating strand of late 19th and early 20th-century art that sought to reconcile classical traditions with modern psychological insights, often through the lens of mythology.

The Greiner family name also appears in a different context of German innovation: the Greiner & Friedrichs company was known for its scientific glass instruments and notably supported Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen by providing X-ray tubes for his groundbreaking experiments. While this is a distinct area of achievement, it speaks to a broader German milieu of technical excellence and innovation during that period.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Myth and Form

Otto Greiner was an artist of immense talent and unwavering dedication. His life was a testament to the pursuit of an artistic ideal rooted in classical beauty, anatomical precision, and the enduring power of myth. Deeply influenced by Max Klinger and nourished by the artistic riches of Rome, he created a body of work that is both technically brilliant and thematically profound. His paintings, drawings, and prints, particularly his monumental depictions of mythological scenes and his sensitive explorations of the human form, secure his position as a significant German artist of his generation. Though his career was curtailed by an early death, Otto Greiner's art continues to speak to us of a world where ancient legends and timeless human dramas are rendered with a compelling and unforgettable visual power. His contribution to the rich tapestry of European Symbolism and his mastery of the graphic line ensure his lasting importance in the annals of art history.