Luca Signorelli stands as a pivotal figure in the Italian Renaissance, an artist whose powerful command of human anatomy and dynamic compositions bridged the gap between the early Renaissance masters and the towering figures of the High Renaissance. Born Luca d'Egidio di Ventura in Cortona, a Tuscan hill town, around 1445 (though some sources suggest as early as 1441), he lived until 1523, witnessing a period of extraordinary artistic ferment. His work, characterized by its vigorous energy, anatomical precision, and dramatic intensity, left an indelible mark on the art world, most notably influencing the great Michelangelo.

Signorelli's legacy is primarily built upon his monumental fresco cycles, particularly the breathtaking depiction of the Last Judgment in Orvieto Cathedral. However, his journey began under the tutelage of one of the era's most intellectually rigorous artists, Piero della Francesca, whose influence instilled in Signorelli a deep understanding of perspective, form, and clarity. Active across central Italy, Signorelli absorbed various influences while forging a distinct and forceful style that continues to command attention.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Luca Signorelli was born into a respectable family in Cortona. His father, Egidio di Ventura, was also a painter, suggesting an early exposure to the craft. His mother's family, the Vasari, provided a connection to another significant figure in art history, Giorgio Vasari, the painter and biographer who would later chronicle Signorelli's life and work. This familial link likely provided Signorelli with certain advantages and connections within the artistic and social circles of Tuscany.

The most significant formative influence on the young artist was his apprenticeship with Piero della Francesca, likely undertaken in the 1460s. Piero, a master of perspective, geometry, and serene, monumental compositions, imparted a foundational understanding of spatial construction and human form. Signorelli absorbed Piero's clarity and intellectual approach, but his own temperament leaned towards greater dynamism and emotional expression.

Following his training, Signorelli was drawn to Florence, the vibrant heart of the Renaissance. There, he encountered the work of leading artists who emphasized anatomical study and energetic movement. The influence of Antonio del Pollaiuolo, known for his intense studies of the human figure in action, and Andrea del Verrocchio, a master sculptor and painter whose workshop trained Leonardo da Vinci and Perugino, is evident in Signorelli's developing style. He assimilated their focus on musculature, tension, and the expressive potential of the human body. His early career saw him working in Arezzo and Urbino, further refining his skills and establishing his reputation. He also likely interacted with Umbrian artists like Benedetto Bonfigli.

Developing a Unique Style: Anatomy, Draughtsmanship, and Drama

Signorelli's artistic identity coalesced around several key strengths that distinguished him from his contemporaries and paved the way for future developments in Renaissance art. His profound interest in the human body, his exceptional skill as a draughtsman, and his flair for dramatic narrative became hallmarks of his work.

Mastery of Anatomy and the Nude

Perhaps Signorelli's most celebrated characteristic is his mastery of human anatomy and his powerful depiction of the nude figure. He possessed a deep understanding of musculature, bone structure, and the way the body moves and bears weight. This knowledge was not merely academic; he translated it into figures brimming with life, energy, and often, intense physical strain. His nudes are not idealized in the serene manner of some contemporaries but are robust, tangible, and expressive.

His frescoes in the Orvieto Cathedral are a testament to this skill, showcasing a vast array of figures in complex poses, their muscles taut, their bodies contorted in the throes of resurrection or damnation. This anatomical precision lent an unprecedented realism and visceral impact to his religious narratives. Giorgio Vasari recounts a poignant, if possibly apocryphal, story illustrating Signorelli's dedication: upon the death of his beloved son in Cortona due to the plague, Signorelli supposedly had the body stripped and drew it meticulously, confronting his grief through the intense study of the form he knew so well. Whether factual or not, the anecdote underscores his reputation for anatomical obsession.

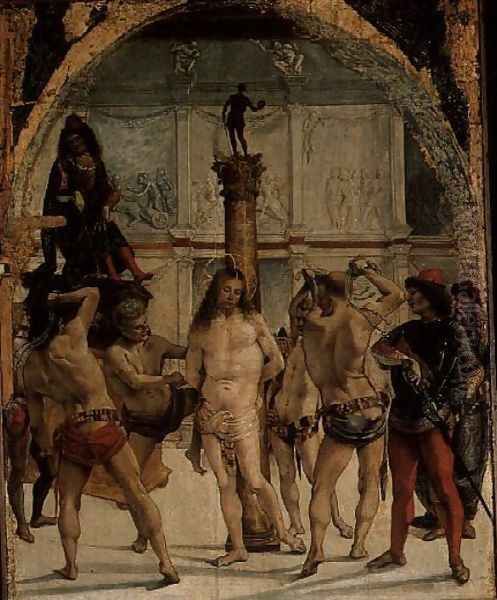

This focus occasionally courted controversy or, at least, invited specific interpretations. His depiction of the tormented Christ in the Flagellation of Christ (Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan), alongside athletic, semi-nude figures, has been noted by some modern critics for its intense physicality and has been described as one of the more homoerotic representations in Western art of the period. This highlights Signorelli's unflinching, sometimes unsettling, exploration of the human form.

Command of Draughtsmanship and Composition

Underpinning Signorelli's anatomical prowess was his exceptional skill as a draughtsman. Drawing was fundamental to his practice, allowing him to work out complex compositions and capture the dynamism of his figures. His preparatory sketches reveal a confident, vigorous line. This linear strength translates into his finished paintings, where figures are clearly defined, possessing a sculptural quality.

He also demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of perspective and foreshortening, likely honed under Piero della Francesca but adapted for more dramatic effect. He used perspective not just to create convincing space but to enhance the narrative impact, often employing low viewpoints or dramatic foreshortening to make figures loom large or recede sharply, adding to the scene's intensity. His compositions are often densely packed with figures, creating a sense of teeming energy and momentous events unfolding.

Use of Light, Shadow, and Color

While renowned for his drawing and anatomy, Signorelli also employed light, shadow (chiaroscuro), and color effectively to enhance the realism and drama of his scenes. He used light to model form, giving his figures a tangible, three-dimensional presence. Shadows are often deep and purposeful, contributing to the emotional atmosphere, particularly in his more dramatic works like the Orvieto frescoes. His color palette could range from relatively bright and clear, especially in earlier works or panel paintings, to more somber and earthy tones in sections of his large fresco cycles, chosen to suit the specific mood or subject matter.

Major Commissions and Masterpieces

Signorelli's talent secured him numerous prestigious commissions throughout central Italy, cementing his reputation as one of the leading masters of his generation. His work graced churches and public buildings, but two major fresco cycles stand out as the pinnacles of his achievement.

The Sistine Chapel Frescoes

In the early 1480s (around 1482-1483), Signorelli was summoned to Rome to participate in one of the most significant artistic projects of the late Quattrocento: the decoration of the walls of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican for Pope Sixtus IV. He joined an elite team of artists, including Sandro Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Cosimo Rosselli, and Pietro Perugino. This commission placed Signorelli among the foremost painters of Italy.

His primary contribution is generally considered to be the fresco depicting the Testament and Death of Moses. While some debate exists regarding the extent of his involvement versus workshop assistance or collaboration (particularly with Bartolomeo della Gatta), the powerful figures, dynamic groupings, and certain stylistic elements strongly align with Signorelli's known work. The scene displays his characteristic energy and anatomical solidity. Working alongside masters like Perugino and Pinturicchio (Bernardino di Betto), who was associated with Perugino's workshop at the time, provided Signorelli with further exposure to different stylistic approaches, particularly the more lyrical Umbrian style, although his own robust Tuscan manner remained dominant.

The Orvieto Cathedral Frescoes: The Last Judgment

Signorelli's magnum opus is undoubtedly the fresco cycle depicting the End of the World and the Last Judgment in the Cappella di San Brizio (Chapel of Saint Brizio) in Orvieto Cathedral. Commissioned in 1499, he took over the project begun decades earlier by Fra Angelico and Benozzo Gozzoli, who had completed only parts of the ceiling vaults. Signorelli worked on the chapel until 1504, creating a cycle of overwhelming power and visionary intensity that remains one of the most significant achievements of the Italian Renaissance.

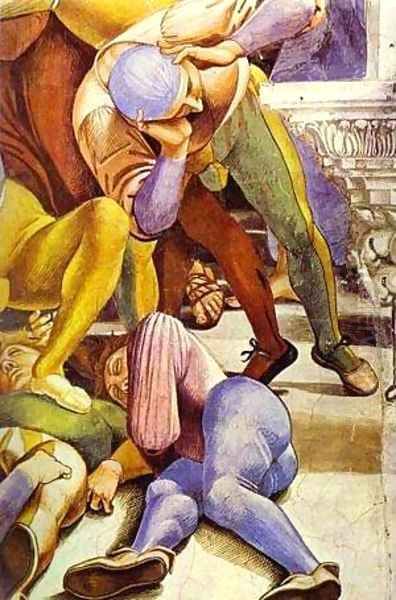

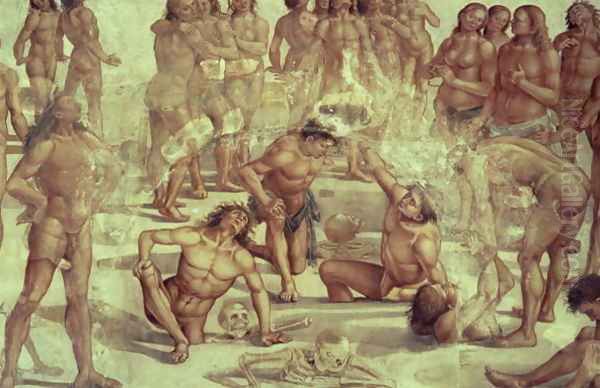

The frescoes cover the walls of the chapel with apocalyptic scenes: The Preaching and Deeds of the Antichrist, The End of the World, The Resurrection of the Flesh, The Damned Cast into Hell, and The Blessed Ascend to Paradise. Signorelli unleashed his full creative power here. The Preaching of the Antichrist is a fascinating scene filled with portraits of contemporaries (including possibly Signorelli himself and Fra Angelico) and a chilling depiction of deception. The Resurrection of the Flesh is a tour-de-force of anatomical drawing, showing skeletons re-clothed in muscle and skin as they claw their way out of the earth.

The most impactful scenes are arguably The Damned and The Blessed. The Damned is a terrifying vision of Hell, a writhing mass of muscular demons tormenting naked human figures. The sheer physicality, the contorted poses, and the raw emotion are shocking and unforgettable. Signorelli's demons are particularly inventive, blending human and bestial forms in grotesque combinations. Conversely, The Blessed depicts serene figures, often nude or lightly draped, welcomed into Paradise by angels, showcasing a softer, though still anatomically grounded, aspect of his art.

The Orvieto cycle was revolutionary in its scale, its dramatic intensity, and its focus on the nude human figure as the primary vehicle for expressing profound theological concepts and extreme emotional states. Its influence was immediate and profound, most notably on Michelangelo, who undoubtedly studied Signorelli's work before undertaking his own Last Judgment on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel decades later. The powerful, muscular figures and dynamic compositions in Michelangelo's masterpiece owe a clear debt to Signorelli's Orvieto frescoes.

Monte Oliveto Maggiore Frescoes

Another significant fresco cycle was undertaken by Signorelli at the Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore, located in Tuscany, south of Siena. Beginning around 1497, he painted nine large frescoes depicting scenes from the life of Saint Benedict of Nursia, the founder of Western monasticism. This project was later completed by Il Sodoma (Giovanni Antonio Bazzi). Signorelli's scenes, such as St. Benedict Recognizes and Receives Totila, demonstrate his narrative skill and ability to manage complex group compositions within architectural settings, though perhaps with less of the overwhelming intensity seen in Orvieto. These works showcase his ability to adapt his style to different subjects and settings.

Other Notable Works

Beyond his major fresco cycles, Signorelli was also a prolific painter of altarpieces and smaller panel paintings. Works like the Madonna and Child (various versions exist, e.g., Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), The Adoration of the Shepherds (National Gallery, London), and portraits demonstrate his versatility. He often depicted saints with characteristic robustness, such as Saint Francis or Saint Dominic. These panel paintings, while sometimes more restrained than the frescoes, still bear the hallmarks of his style: strong drawing, solid figures, and often, a thoughtful or intense psychological presence. The Lamentation over the Dead Christ, painted for a church in Cortona and now housed in the Diocesan Museum there, is a particularly moving example of his later work, combining anatomical realism with deep pathos.

Collaborations and Contemporaries

Signorelli's career unfolded during a period rich with artistic talent. His interactions, collaborations, and rivalries shaped his path. His early work alongside Perugino and Pinturicchio in the Sistine Chapel was significant. While influenced by Perugino's sweeter, more graceful Umbrian style, Signorelli maintained his distinct Tuscan emphasis on power and anatomical structure. He represents a different facet of the Umbrian-Tuscan artistic exchange, contrasting with the more lyrical approach of Perugino or the decorative richness of Pinturicchio.

He was a contemporary of Leonardo da Vinci, though their styles differed significantly, with Leonardo pursuing sfumato and psychological subtlety while Signorelli focused on clarity of form and dramatic action. He knew Filippino Lippi and other Florentine masters. His relationship with Piero della Francesca remained foundational, and he can be seen alongside artists like Melozzo da Forlì as inheritors of Piero's legacy, each taking it in a unique direction – Melozzo known for his mastery of foreshortening ('sotto in sù'), Signorelli for his dynamic anatomy.

Ultimately, Signorelli's position in art history is often defined by his relationship to the generation that followed him. His work served as a crucial stepping stone for Michelangelo and Raphael. While both surpassed him in fame and perhaps in the breadth of their influence, Signorelli's innovations, particularly in the depiction of the active nude figure and complex, dramatic compositions, were essential precedents for their High Renaissance achievements.

Civic Life and Later Years

Beyond his artistic endeavors, Luca Signorelli was an active participant in the civic life of his hometown, Cortona. He held various important municipal positions throughout his life, serving on councils and acting as a magistrate. This indicates he was a respected citizen, well-integrated into the social and political fabric of his community. His continued connection to Cortona is evident, as he frequently returned there between commissions and spent his final years in the city.

In his later career, while still receiving commissions, Signorelli witnessed the meteoric rise of younger artists, particularly Michelangelo and Raphael, whose work came to define the High Renaissance. While Signorelli's powerful style remained respected, the artistic tastes, particularly in major centers like Rome and Florence, began to shift towards the grace, harmony, and idealized beauty perfected by Raphael, or the sublime, superhuman energy of Michelangelo. Vasari notes that Signorelli maintained a grand lifestyle, dressing well and living honorably.

Despite being somewhat overshadowed in his final years by the next generation, Signorelli continued to work, often with the assistance of a workshop, producing altarpieces for local churches in Cortona, Umbria, and the Marche. He died in Cortona in 1523, reportedly while working on a fresco at the Villa Passerini near the city, bringing a long and remarkably productive artistic life to a close at an advanced age (around 80 years old).

Legacy and Influence

Luca Signorelli's importance in the history of Italian Renaissance art is undeniable. He was a master innovator, particularly in the realm of anatomical representation and the depiction of the human figure in dynamic action. His work represents a powerful fusion of Tuscan strength, Florentine anatomical inquiry, and Umbrian narrative traditions, all forged into a unique and forceful personal style.

His most significant legacy lies in his influence on Michelangelo. The Orvieto frescoes, with their teeming crowds of muscular nudes in dramatic poses, directly prefigure Michelangelo's Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel. Signorelli's bold exploration of the expressive potential of the human body provided a crucial precedent for Michelangelo's own titanic figures. While Raphael's art developed along different lines, the general High Renaissance interest in complex figure composition and anatomical accuracy owes a debt to pioneers like Signorelli.

Although his name might not possess the immediate universal recognition of Leonardo, Michelangelo, or Raphael, Signorelli remains a giant of the Quattrocento and early Cinquecento. He stands as a vital link between the Early Renaissance focus on perspective and naturalism (as exemplified by his teacher, Piero della Francesca) and the High Renaissance's mastery of complex composition, dynamic movement, and the idealized yet powerful human form. His works, particularly the Orvieto cycle, continue to astound viewers with their visionary power, technical brilliance, and profound exploration of the human condition at its most extreme moments. Giorgio Vasari's biography ensured his place in the canon, recognizing him as a key figure in the trajectory towards the perfection Vasari saw embodied in Michelangelo.

Conclusion

Luca Signorelli was more than just a precursor; he was a master in his own right. From his rigorous training under Piero della Francesca to his mature works in Rome, Orvieto, and Tuscany, he consistently pushed the boundaries of painting. His profound understanding of anatomy, his vigorous draughtsmanship, and his ability to orchestrate complex, dramatic narratives set a new standard for the depiction of the human figure. The frescoes of the Cappella di San Brizio in Orvieto remain his enduring testament—a work of terrifying beauty and visionary power that secured his place among the great innovators of the Italian Renaissance and profoundly shaped the course of Western art. His art continues to resonate through its sheer energy, its intellectual depth, and its unflinching gaze into the extremes of human experience.