Jan Gossaert, also known during his lifetime and for centuries after as Jan Mabuse (or Jennyn van Hennegouwe), stands as a pivotal figure in the history of Northern European art. Active from the late 15th century until his death in 1532 (born circa 1478), Gossaert was among the very first artists from the Low Countries to travel to Italy and consciously absorb the principles of the Italian Renaissance, subsequently introducing these revolutionary ideas to his homeland. His work represents a fascinating synthesis, blending the established, detail-rich tradition of Netherlandish painting with the newfound classical ideals of form, anatomy, and mythological subject matter encountered south of the Alps. He was, in essence, a bridge-builder, navigating the complex artistic currents of a transformative era.

Early Life and Formation in the Netherlandish Tradition

Born around 1478 in Maubeuge, located in the County of Hainaut (then part of the Burgundian Netherlands and the origin of his moniker "Mabuse"), Gossaert's early training likely occurred within the vibrant artistic milieu of the Low Countries. While details of his initial apprenticeship remain obscure, it is clear that he absorbed the dominant artistic language of the region, characterized by meticulous detail, rich textures, luminous oil glazes, and often complex religious symbolism, exemplified by masters like Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden from the previous generation.

By 1503, Gossaert had achieved sufficient mastery to be accepted into the prestigious Guild of Saint Luke in Antwerp, then rapidly becoming the economic and artistic hub of Northern Europe. His early works from this period, though sometimes difficult to date precisely, show a strong grounding in this Netherlandish heritage. Works like the Virgin and Child with a Lily (circa 1503) demonstrate his skill in rendering textures and devotional sentiment, albeit already hinting at a certain solidity of form that would later be amplified. He was working alongside prominent Antwerp contemporaries such as Quentin Matsys, who was himself exploring new avenues of expression, particularly in portraiture and genre scenes.

The Transformative Journey to Rome

A defining moment in Gossaert's life and artistic development occurred in 1508. He joined the diplomatic mission of Philip of Burgundy – an illegitimate son of Duke Philip the Good, an admiral of Flanders, and a significant humanist patron – to the papal court of Pope Julius II in Rome. This journey, lasting until 1509, exposed Gossaert directly to the heart of the Italian Renaissance and the overwhelming presence of classical antiquity. Unlike earlier Northern artists who might have known Italian art through prints or scattered examples, Gossaert experienced it firsthand.

In Rome, Gossaert was captivated. He diligently studied and sketched ancient Roman sculptures, marveling at their anatomical accuracy, idealized forms, and dynamic poses. Surviving drawings attest to his fascination with works like the Spinario or the sculptures found in private collections like that of the Sassi family. He also observed the groundbreaking works of contemporary Italian masters. While direct documented encounters are lacking, he was in Rome during a period of intense artistic activity, with Michelangelo working on the Sistine Chapel ceiling and Raphael beginning his stanze in the Vatican. The impact of High Renaissance ideals – harmony, proportion, classical grandeur, and the confident depiction of the human form – was profound. He sketched classical architecture, such as the Temple of Hercules Victor (often then misidentified), absorbing its proportions and decorative motifs.

Forging a New Path: Italianism Meets Northern Realism

Upon his return to the Low Countries, Gossaert embarked on the ambitious project of integrating his Italian experiences into his native artistic tradition. He became a leading proponent of what art historians call "Romanism" – the conscious adoption of Italian Renaissance forms, themes (especially mythology and the nude), and compositional strategies by Northern artists. This was not mere imitation; Gossaert sought a synthesis.

His paintings began to feature figures with greater volume and more anatomically convincing structures, often placed within elaborate classical architectural settings. He adopted Italian techniques like chiaroscuro (the use of strong contrasts between light and dark) to enhance plasticity and drama. Yet, he rarely abandoned the Northern penchant for meticulous detail, rich surface textures, and jewel-like colours, sometimes using expensive pigments like ultramarine blue derived from lapis lazuli. This fusion created a unique, sometimes eclectic style. The classical architecture in his paintings, while impressive, often retains a decorative, almost fantastical quality rather than strict archaeological accuracy, filtered through a Northern sensibility.

Masterpieces and Key Themes: Religion, Mythology, and Portraiture

Gossaert's oeuvre spans the major genres of his time: religious paintings, mythological subjects, and portraits. His trip to Italy significantly impacted his approach to all three.

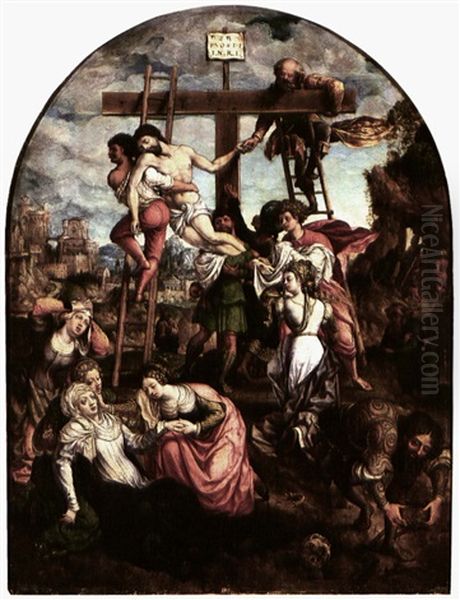

Religious Works: While continuing to paint traditional Christian themes, Gossaert infused them with Renaissance monumentality and anatomical understanding. His depictions of the Madonna and Child, for example, often show fuller, more sculptural figures than typical earlier Netherlandish examples. A notable work is St. Luke Painting the Virgin, of which versions exist (e.g., in Vienna and Prague). These complex compositions often feature the artist (St. Luke) within an elaborate architectural space, showcasing Gossaert's command of perspective and his ability to blend devotional intimacy with Renaissance grandeur. The figures possess a weight and presence influenced by Italian models.

Mythological Subjects and the Nude: Gossaert was a true pioneer in introducing classical mythology and the idealized nude figure as major subjects in Northern painting. Works like Neptune and Amphitrite (1516), painted for Philip of Burgundy's Souburg Castle, are landmark achievements. The life-sized, statuesque nudes, clearly inspired by classical sculpture, stand within a rigorously designed classical architectural frame. Similarly, his Danaë (c. 1527) depicts the mythological princess in a richly decorated Italianate interior, showered with gold – a subject favoured in Italy but novel in the North. These works were bold statements, showcasing humanist learning and a new appreciation for the beauty of the human body, distinct from purely religious contexts.

His depictions of Adam and Eve (e.g., the version circa 1520) are particularly significant. While the theme was traditional, Gossaert treated the figures with unprecedented anatomical realism and sensuousness, drawing inspiration from both classical sculpture and potentially prints by artists like Albrecht Dürer or even Leonardo da Vinci, whose influence permeated European art circles. He experimented with poses and compositions, moving beyond the stiffer conventions of earlier Northern depictions.

Portraiture: Gossaert was also a highly sought-after portraitist. He served various members of the Burgundian court and other wealthy patrons. His portraits, such as the engraved likeness of Christian II of Denmark (1523) or painted portraits of aristocrats, combine the Netherlandish tradition of sharp observation and detailed rendering of costume and status symbols with a new sense of psychological presence and physical volume derived from Italian examples. He captured the likeness and stature of his sitters, often placing them in sophisticated settings that underscored their importance. His patrons included not only Philip of Burgundy but also Margaret of Austria, Regent of the Netherlands.

The Nude as Innovation and Controversy

Gossaert's introduction of the large-scale mythological nude into Netherlandish art was arguably his most radical innovation. Before him, the nude in Northern art was largely confined to depictions of Adam and Eve or souls in Last Judgment scenes, often rendered with a degree of gothic angularity or symbolic meaning rather than classical idealization. Gossaert’s nudes, inspired by antiquity and Italian masters like Michelangelo, aimed for anatomical correctness and idealized beauty.

This move was not without its complexities. Some later critics, and perhaps even some contemporaries, found his nudes occasionally awkward, caught between classical idealization and Northern realism. The figures in Neptune and Amphitrite, for instance, while imposing, have a certain stiffness compared to their Italian counterparts. His Adam and Eve figures, while anatomically studied, possess a fleshy naturalism that differs from the more ethereal or heroic quality often found in Italian High Renaissance nudes. These works sparked debate: was this a successful adaptation of the classical ideal, or did it remain somewhat artificial, a learned exercise rather than a fully internalized aesthetic? Regardless, Gossaert opened the door for subsequent generations of Northern artists to explore the nude figure with greater confidence.

Gossaert Among Contemporaries

Understanding Gossaert requires placing him within the network of artists active during his time. In Antwerp, he worked alongside Quentin Matsys and Joos van Cleve, both significant painters contributing to the city's artistic dynamism. His Romanist inclinations connected him to artists like Bernard van Orley in Brussels, who also looked towards Italy.

His relationship with the German master Albrecht Dürer is intriguing. While direct personal contact isn't firmly documented (though Dürer visited the Low Countries in 1520-21 and met Matsys and van Orley), their works show mutual awareness. Gossaert adapted motifs from Dürer's prints, and Dürer himself seems to have been interested in Gossaert's interpretations. Both artists grappled with integrating Italian Renaissance ideas, though Dürer's approach was perhaps more analytical and print-focused.

Regarding the Italian giants, Gossaert clearly admired Michelangelo and Raphael, whose influence is discernible in the monumentality and compositional structures of his later works. He may also have been aware of the work of Venetian artists or earlier masters interested in antiquity like Andrea Mantegna. Another relevant figure is Jacopo de' Barbari, an Italian artist who worked in the North and may have provided an earlier example of Italian influence. Gossaert's engagement with these diverse sources highlights the increasingly interconnected European art world of the early 16th century. He stands apart from slightly later Netherlandish artists like Pieter Bruegel the Elder, who, while also visiting Italy, ultimately pursued a path more deeply rooted in local traditions and social commentary.

Later Career and Legacy

After Philip of Burgundy's death in 1524, Gossaert continued to find patronage, working for Philip's successors and other members of the Habsburg court, including Margaret of Austria. He worked in various locations, including Utrecht and Middelburg, where he eventually died in 1532.

Gossaert's legacy was substantial. He firmly established Romanism as a significant trend in Netherlandish art. His willingness to tackle complex mythological themes and his pioneering use of the nude paved the way for later artists. While subsequent generations developed the synthesis of North and South in different directions, Gossaert's initial steps were crucial. His influence can be seen in the work of artists like Jan van Scorel and Maerten van Heemskerck, who also traveled to Italy. More broadly, his elevation of classical themes and forms contributed to the humanist culture flourishing in the Low Countries.

Art historians continue to debate the precise nature of his achievement. Was he a truly transformative figure who successfully integrated two distinct artistic traditions, or was his Italianism sometimes superficial, a veneer of classical motifs over a fundamentally Northern core? Some argue his strength remained in the meticulous execution inherited from the Van Eyck tradition, while others praise his bold experimentation. His work sometimes lacks the effortless grace of a Raphael or the dramatic intensity of a Michelangelo, possessing instead a unique, sometimes Mannerist-tinged elegance characterized by elongated forms, intricate details, and a cool, enamel-like finish.

Despite these debates, Jan Gossaert's importance is undeniable. He was a crucial conduit through which the visual language of the Italian Renaissance flowed northward. His ambition, his technical skill, and his willingness to embrace new forms and subjects mark him as a key figure of the Northern Renaissance. His work laid important groundwork for the spectacular flourishing of Flemish art in the following century, particularly in the grand compositions of Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck, who would achieve an even more dynamic and fully integrated synthesis of Northern and Southern European artistic traditions. Gossaert remains a testament to the vibrant cross-cultural exchanges that defined the Renaissance era.