Otto Gutfreund stands as a monumental figure in the landscape of early 20th-century European art, particularly celebrated as a foundational pioneer of Czech Cubist sculpture. His innovative approach to three-dimensional form, deeply influenced by the revolutionary currents of his time, carved a unique niche for Czech art on the international stage. Gutfreund's journey was one of bold experimentation, intellectual rigor, and a profound engagement with the shifting cultural and political tides, leaving behind a legacy that continues to inspire and provoke.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born on August 3, 1889, in Dvůr Králové nad Labem, Bohemia (then part of Austria-Hungary, now the Czech Republic), Otto Gutfreund's artistic inclinations emerged early. He initially pursued studies at the local School of Pottery in Bechyně from 1903 to 1906, an experience that likely provided him with a fundamental understanding of material and form. However, his ambitions soon led him to the bustling artistic center of Prague, where he enrolled at the School of Applied Arts (Uměleckoprůmyslová škola, UMPRUM) in 1906, studying there for three years.

This period in Prague was formative, exposing Gutfreund to the burgeoning modernist movements that were beginning to challenge academic traditions. The city was a vibrant hub of artistic and intellectual activity, with artists keenly aware of developments in Paris, Vienna, and Berlin. It was here that Gutfreund began to absorb the influences that would shape his early artistic identity, likely encountering the works and ideas of Expressionism and the nascent stirrings of Cubism through journals and exhibitions.

The Parisian Crucible: Embracing Cubism

The allure of Paris, the undisputed capital of the avant-garde, proved irresistible. In 1909, Gutfreund relocated to the French capital to further his studies, enrolling in the private school of Antoine Bourdelle, a former assistant to Auguste Rodin. Bourdelle, while rooted in a more classical tradition, was himself moving towards a more monumental and simplified form, and his tutelage provided Gutfreund with a strong sculptural foundation. However, it was the radical innovations of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque that truly captivated the young Czech sculptor.

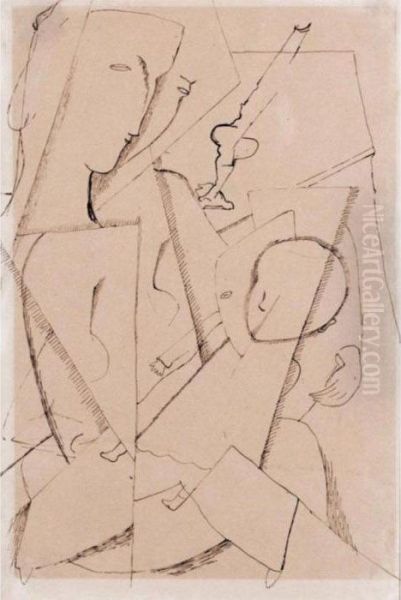

The Cubist revolution, with its fragmentation of objects, its depiction of multiple viewpoints simultaneously, and its emphasis on geometric structure, was primarily a painterly phenomenon. Gutfreund was among the very first artists to grapple with the profound challenge of translating these principles into the three-dimensional medium of sculpture. He immersed himself in the Parisian art scene, frequenting galleries, studios, and cafes where artists and intellectuals debated the future of art. He would have undoubtedly encountered the works of other sculptors beginning to explore similar paths, such as Alexander Archipenko, Jacques Lipchitz, and Raymond Duchamp-Villon, each seeking to break free from traditional sculptural representation.

Gutfreund’s engagement with Cubism was not mere imitation. He sought to understand its underlying structural and conceptual logic, adapting it to the inherent demands of volume and space. This period, from roughly 1911 to the outbreak of World War I, marked his most intensely Cubist phase, producing works that are now considered landmarks of the movement.

Defining Works of Czech Cubism

Gutfreund's genius lay in his ability to imbue the geometric rigor of Cubism with a potent emotional and psychological charge. His sculptures from this era are characterized by their dynamic interplay of faceted planes, sharp angles, and a sense of contained energy.

One of his earliest and most significant Cubist sculptures is "Úzkost" (Anxiety), created in 1911-1912. This powerful bronze work depicts a seated figure, its form broken down into crystalline shards and concave hollows. The figure’s posture and the fragmented surfaces convey a profound sense of inner turmoil and unease, demonstrating Gutfreund's skill in using Cubist vocabulary to express complex human emotions. It was a groundbreaking piece, showcasing how the analytical deconstruction of form could paradoxically heighten expressive intensity.

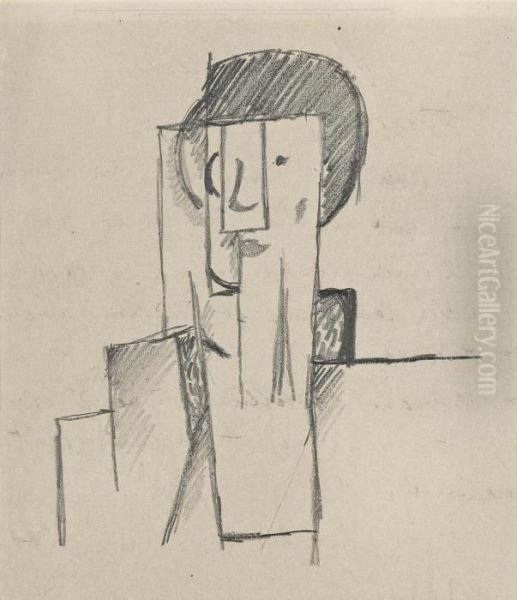

Another iconic work from this period is "Don Quixote" (1911-1912). Here, Gutfreund tackles a literary subject, rendering the famous knight not as a literal representation but as an embodiment of his tragicomic idealism. The sculpture’s elongated, almost precarious forms and the interplay of solid masses and voids capture the essence of Quixote's character. The head, a complex assembly of geometric planes, suggests both a helmet and a face etched with determination and perhaps delusion.

His "Hamlet" (c. 1912-1913) continued this exploration of literary figures through a Cubist lens. The sculpture captures the introspective and tormented nature of Shakespeare's prince, using angular, intersecting planes to suggest psychological depth and conflict. These works, alongside others, established Gutfreund as a leading voice in the international Cubist movement, and certainly the foremost Cubist sculptor in Bohemia. He was an active participant in the Prague avant-garde, associated with groups like the Mánes Union of Fine Arts (Spolek výtvarných umělců Mánes), which included prominent painters like Emil Filla, Josef Čapek, Vincenc Beneš, and Bohumil Kubišta, all of whom were exploring Cubism in their respective ways.

War, Captivity, and Artistic Reflection

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 dramatically interrupted Gutfreund's burgeoning career. Residing in Paris, he, like fellow Czech artist František Kupka, volunteered for the French Foreign Legion. He served on the front lines in Alsace for two years. This direct experience of conflict undoubtedly left an indelible mark on him.

In 1916, his military service took a harsh turn when he was discharged and subsequently interned in a French civilian prisoner-of-war camp at Saint-Michel de Frigolet. He would spend nearly three years in captivity, a period of hardship and isolation. While the conditions were undoubtedly difficult, this time may have also offered moments for reflection on his art and the tumultuous state of the world. The war years forced many artists to reconsider their pre-war avant-garde ideals, and Gutfreund was no exception.

Post-War Return and the "Civilist" Phase

After the war's end and the establishment of the independent Czechoslovak Republic in 1918, Gutfreund returned to Prague in 1920. The artistic landscape had shifted, and so had Gutfreund. While he initially revisited Cubist principles, his style began to evolve towards what is often termed "Civilism" or "Social Realism," though it retained a modern sensibility. This phase, prominent in the early to mid-1920s, saw him create works that were more accessible, often depicting everyday life, labor, and figures embodying the spirit of the new nation.

This shift was not unique to Gutfreund; many European artists in the post-war era moved towards a "return to order" or a more socially engaged form of art. For Gutfreund, this meant creating sculptures that could resonate with a broader public and contribute to the cultural identity of the newly formed Czechoslovakia. Works from this period often featured rounded, more naturalistic forms, though still stylized and imbued with a modern sense of design. He created numerous public commissions, including reliefs and monuments.

One of his notable later works, though perhaps conceived earlier or bridging his styles, is "Okřídlený šíp" (The Winged Arrow), a dynamic sculpture that, while retaining some Cubist fragmentation, also possesses a streamlined, almost Art Deco quality. This piece, like many of his works, found a home in significant Czech collections, including the National Gallery Prague and the Kampa Museum, which also holds works by his contemporary František Kupka.

Teaching, Theoretical Contributions, and Continued Influence

Upon his return to Prague, Gutfreund became an influential figure in the Czech art scene not only as a practicing artist but also as an educator. In 1926, he was appointed professor at the School of Applied Arts (UMPRUM) in Prague, the very institution where he had begun his advanced studies. In this role, he had the opportunity to shape a new generation of Czech artists.

Beyond his sculptural practice and teaching, Gutfreund also contributed to art theory, writing essays on sculpture. These writings articulated his evolving thoughts on form, space, and the role of sculpture in modern society. He remained an active member of the Mánes Union of Fine Arts, participating in its exhibitions and contributing to its intellectual life. His work continued to be exhibited internationally, and pieces were acquired by prestigious institutions, including the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, attesting to his growing international reputation.

His circle of influence and interaction extended to many key figures in the Czech avant-garde. Beyond Filla and Kupka, he would have been aware of and interacted with architects like Pavel Janák and Josef Gočár, who were pioneering Czech Cubist architecture, a unique phenomenon where Cubist principles were applied to building design. His work was also exhibited alongside later generations of Czech artists, such as Karel Nepraš, Magdalena Jetelová, Alena Kučerová, and Stanislav Kolíbal, demonstrating his lasting impact on the trajectory of Czech modern art. The collector Eric Estorick was also a significant acquirer of his work, further helping to cement his international standing.

Legacy and Critical Debates

Otto Gutfreund's legacy is multifaceted. He is undeniably a key figure in the history of Cubism, particularly for his early and insightful translation of its principles into sculpture. His pre-war Cubist works are considered masterpieces of the movement, demonstrating a unique fusion of analytical structure and emotional depth.

However, his career has also been subject to art historical debate. Some critics, particularly during his early Cubist phase, suggested his work was overly derivative of Picasso. While the influence of Picasso and Braque is undeniable – as it was for virtually all artists engaging with Cubism – Gutfreund’s sculptural interpretations possess a distinct character and intensity. His ability to convey psychological states like anxiety through fragmented form was a significant contribution.

His post-war shift towards "Civilism" has also been viewed through different lenses. Some see it as a pragmatic response to the socio-political realities of the new Czechoslovak Republic, an attempt to create a more publicly accessible and nationally relevant art. Others might view it as a tempering of his earlier radical avant-gardism, perhaps a move away from the intellectual complexities of Cubism towards a more populist aesthetic. This tension between avant-garde exploration and social engagement is a recurring theme in the careers of many 20th-century artists who lived through such profound societal upheavals.

His proposals for public art projects, sometimes in collaboration with architects, were often innovative and dynamic, challenging traditional notions of monumental sculpture. These, too, sometimes sparked controversy due to their departure from established conventions. Despite these debates, his importance within Czech modernism is undisputed, and his influence on subsequent generations of sculptors is significant.

A Tragic End and Enduring Significance

Tragically, Otto Gutfreund's prolific career and life were cut short. On June 2, 1927, at the age of just 38, he drowned while swimming in the Vltava River in Prague. His premature death was a significant loss to Czech and international art. He left behind a body of work that, though produced over a relatively short period, marked a pivotal moment in the development of modern sculpture.

Otto Gutfreund's sculptures remain powerful testaments to an era of artistic revolution. He successfully navigated the complex transition from the expressive intensity of early modernism to the analytical rigor of Cubism, and then to a more socially conscious art in the post-war period. His ability to synthesize these diverse currents, particularly in his pioneering Cubist works like "Anxiety" and "Don Quixote," secures his place as one of the most important sculptors of the early 20th century. His work continues to be studied and admired for its formal innovation, its emotional resonance, and its crucial role in defining Czech modernism. He remains a vital link in the international story of Cubism, demonstrating its adaptability and power beyond the canvas and into the tangible realm of three-dimensional form.