Julio González (1876-1942) stands as a pivotal figure in the evolution of twentieth-century sculpture. A Spanish artist who spent much of his productive life in Paris, González uniquely bridged the worlds of traditional craftsmanship and avant-garde art. He is celebrated primarily for his revolutionary use of welded iron, transforming an industrial material and technique into a powerful medium for artistic expression. His concept of "drawing in space" fundamentally altered the understanding of sculptural form, moving away from solid mass towards linear, open constructions that defined volume through line and void. His close association with Pablo Picasso and his profound influence on subsequent generations of sculptors solidify his legacy as a true innovator.

From Barcelona's Workshops to Parisian Avant-Garde

Julio González i Pellicer was born in Barcelona in 1876 into a family deeply rooted in the tradition of metalworking. His father, Concordio González, was a respected goldsmith and sculptor, and the family workshop was a hub of artistic craft, producing decorative metalwork that aligned with the flourishing Catalan Modernisme movement. Julio and his older brother, Joan, received their initial training here, mastering techniques like forging, casting, and repoussé from a young age. This early immersion in the craft of metal provided González with an unparalleled technical foundation that would later define his sculptural practice.

Alongside his craft training, González pursued fine art, studying drawing and painting at the Barcelona School of Fine Arts (La Llotja). He frequented Els Quatre Gats, the legendary café that served as a meeting point for Barcelona's bohemian artists and intellectuals, including a young Pablo Picasso, whom he first met around the turn of the century. During these early years, González worked primarily as a painter and metalsmith, creating intricate decorative objects, jewelry, and masks, often exhibiting alongside his brother Joan. His early paintings showed influences from Impressionism and Symbolism.

Seeking broader artistic horizons, González moved to Paris in 1900, joining a vibrant community of expatriate Spanish artists. He settled in Montmartre, renewing his friendship with Picasso and becoming acquainted with other key figures of the burgeoning avant-garde, such as Constantin Brancusi, Manolo Hugué, and his compatriot Pablo Gargallo, another sculptor exploring metal. Despite the stimulating environment, González initially continued to focus primarily on painting and drawing, struggling to find his distinct artistic voice amidst the radical innovations of Fauvism and early Cubism.

The death of his beloved brother Joan in 1908 was a profound blow, leading to a period of depression and reduced artistic output. For years, González grappled with his direction, torn between painting and the metalworking craft he knew so intimately. He continued to create metal objects and masks, but his ambition lay in establishing himself as a painter. However, the skills honed in his father's workshop remained latent, waiting for the right catalyst to merge with his fine art aspirations.

The Turn to Sculpture and the Picasso Collaboration

The decisive shift in González's career occurred relatively late, in his early fifties. Around 1927, encouraged by his friend, the sculptor Pablo Gargallo, who was already experimenting with cut and assembled sheet metal, González began to dedicate himself more seriously to sculpture, specifically using iron. He started exploring the possibilities of direct metalworking, particularly forging and welding, techniques familiar from his youth but now applied to purely artistic ends. This marked a departure from traditional sculpture based on carving stone or modeling clay for casting.

A crucial turning point came between 1928 and 1931, when Pablo Picasso sought González's technical expertise. Picasso, eager to translate his Cubist ideas into three-dimensional metal forms but lacking the necessary welding skills, turned to his old friend. González possessed the mastery of oxy-acetylene welding, a relatively new industrial technique he had learned while working briefly in a Renault factory during World War I. This collaboration proved immensely fruitful for both artists.

González assisted Picasso in realizing several significant welded iron sculptures, including the seminal Woman in the Garden (Femme au jardin). While Picasso provided the radical artistic vision, González provided the technical means, teaching Picasso how to weld and helping construct the complex forms. This intense period of collaboration was transformative for González. Working alongside Picasso, he absorbed Cubist principles of deconstruction and spatial analysis, but more importantly, he gained the confidence to fully embrace iron as his primary medium and welding as his signature technique. He saw the potential to create a new kind of sculpture – open, linear, and dynamic.

The collaboration freed González from the constraints of traditional metalcraft and pushed him towards abstraction. He began to see the rods and sheets of iron not just as materials to be shaped, but as lines and planes that could actively delineate space. This period cemented his path as a sculptor and laid the groundwork for his most innovative contributions to modern art. While their intense collaboration waned after 1931, the mutual respect and artistic dialogue between González and Picasso continued.

Drawing in Space: A New Sculptural Language

Emerging from the collaboration with Picasso, Julio González fully developed his revolutionary concept of "drawing in space" (dibujar en el espacio). This idea represented a fundamental break from the tradition of sculpture as solid mass. Instead of carving away material or building up volume with clay, González used slender iron rods and cut metal sheets, joined by welding, to create open, airy structures that suggested form and volume through lines and planes interacting with the surrounding space.

His sculptures became linear constructions where the void, the empty space enclosed or defined by the metal elements, was as important as the material itself. He effectively used metal lines to sketch three-dimensional forms in the air, creating works that possessed a lightness and transparency previously unseen in metal sculpture. This approach resonated with the spatial explorations of Cubism and Constructivism but was uniquely realized through the specific properties of welded iron.

Works from the early 1930s, such as Harlequin and The Dream (also known as Le Baiser or The Kiss), exemplify this new language. They feature delicate arrangements of rods and small planes, suggesting figures or objects with minimal material means. The weld points, often left visible, became part of the aesthetic, emphasizing the process of construction and the industrial nature of the medium. González demonstrated that iron, often associated with weight and industry, could be used to create forms of great elegance, dynamism, and even tenderness.

This innovative approach required immense technical skill. González's mastery of welding allowed him to join disparate metal elements with precision, creating seemingly effortless lines and complex spatial relationships. He controlled the flow of molten metal to create joints that were both structurally sound and aesthetically integrated into the overall composition. His deep understanding of the material, gained over decades, enabled him to push its boundaries in unprecedented ways.

Mature Style: Abstraction, Figuration, and Expression

Throughout the 1930s, González's style continued to evolve, balancing abstraction with figurative references. While he embraced the openness and linearity of "drawing in space," his work often retained connections to the human form, particularly the female figure. Sculptures like Woman Combing Her Hair (Mujer peinándose, c. 1936) masterfully blend abstract spatial construction with the suggestion of a human gesture. The figure is reduced to essential lines and planes, yet it conveys a sense of movement and intimacy.

González explored various themes, including masks, heads, and reclining figures. His masks, often incorporating found objects or textured surfaces, recall both African tribal art – an influence shared with Picasso and other modernists like Amedeo Modigliani – and the metal masks from his early craft period. These works often carry a psychological intensity, exploring identity and concealment. The heads, ranging from near-abstract constructions to more recognizable forms, demonstrate his ability to convey character and emotion through minimal means.

His materials remained predominantly iron and bronze (often cast from iron originals), and his technique centered on welding and forging. He valued the raw quality of the metal, often leaving surfaces rough or textured, allowing the material's inherent character to contribute to the work's expressive power. This direct engagement with industrial materials positioned him as a forerunner of later developments in sculpture.

The looming political crises in Europe, particularly the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), deeply affected González. His work took on a more dramatic and sometimes anguished tone. This period saw the creation of some of his most powerful and iconic sculptures, reflecting the suffering and resilience of the human spirit in times of conflict. His art, while often abstract, became imbued with profound human feeling.

Major Works: Icons of Modern Sculpture

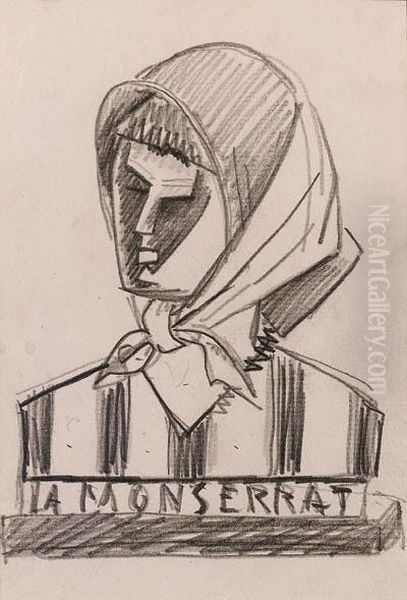

Julio González's oeuvre includes several masterpieces that have become icons of modern sculpture. Among the most significant is La Montserrat (1936-1937). Created for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 Paris International Exposition – the same pavilion that housed Picasso's Guernica – this sculpture is one of González's most explicitly figurative and emotionally charged works. It depicts a Catalan peasant woman, holding her child and screaming towards the sky, a powerful symbol of maternal strength, suffering, and resistance against the backdrop of the Spanish Civil War. Made from hammered sheet iron, it possesses a raw, expressive force, contrasting with the more linear abstraction of much of his other work but demonstrating his versatility and depth.

Another key work is Woman Combing Her Hair (c. 1936). This sculpture is a quintessential example of "drawing in space." Using slender iron rods and strategically placed planes, González evokes the elegant posture and intimate action of a woman arranging her hair. The form is radically simplified, yet instantly recognizable and imbued with grace. The interplay between the solid metal lines and the open space they define creates a dynamic sense of volume and movement. It showcases his ability to blend abstraction and figuration seamlessly.

The Head of the Little Montserrat Screaming (Cabeza de la pequeña Montserrat gritando, 1936-1937), a study related to the larger La Montserrat, is a powerful work in its own right. This bronze head captures the anguish and intensity of the larger figure in a concentrated form, highlighting González's skill in conveying strong emotion through sculptural means.

Later works, such as the Cactus Man series (Hombre Cactus, c. 1939-1940), push further into abstraction while retaining an organic, almost tortured quality. These figures, composed of spiky, aggressive forms welded together, seem to embody pain and resilience. They can be interpreted as responses to the escalating violence in Europe leading up to World War II, reflecting a sense of anxiety and defiance. These works demonstrate González's continued experimentation with form and expression even in his final years.

Other notable works include Daphne (c. 1937), inspired by the mythological figure transforming into a tree, which masterfully uses branching iron forms to suggest metamorphosis, and various abstract heads and figures that explore complex spatial relationships through welded planes and lines, such as Head Called 'The Tunnel' (c. 1933-35) and Abstract Sculpture (Harlequin) (c. 1930).

The Spanish Civil War and Final Years

The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 profoundly impacted Julio González, both personally and artistically. Though living in France, he felt a deep connection to his homeland and anguish over the conflict. This turmoil found expression in his work, most notably in La Montserrat, which became an enduring symbol of Spanish suffering and resistance, shown alongside Picasso's monumental anti-war statement, Guernica, and Joan Miró's The Reaper (now lost) in the Spanish Republic's Pavilion at the 1937 Paris Exposition.

The war years and the subsequent German occupation of Paris during World War II were difficult for González. Materials became scarce, limiting his ability to work in welded iron. He turned increasingly to drawing and modeling in plaster, creating numerous studies and smaller pieces. His drawings from this period often possess the same linear energy and spatial complexity as his sculptures, further blurring the lines between two-dimensional and three-dimensional expression.

Despite the hardships, his creativity did not cease. He continued to explore themes of suffering, metamorphosis, and the human condition. The Cactus Man figures, with their sharp, defensive forms, are powerful expressions from this late period, reflecting the harsh realities of war and occupation. They suggest figures under duress, bristling yet enduring.

Julio González died suddenly in Arcueil, near Paris, in March 1942, at the age of 65, during the German occupation. He did not live to see the end of World War II or the full extent of his influence on the art world. However, he left behind a body of work that had irrevocably changed the course of modern sculpture. His dedication to his craft, his innovative spirit, and his ability to imbue industrial materials with profound human emotion secured his place as a master of twentieth-century art.

Influence and Lasting Legacy

Julio González's impact on subsequent sculpture is immense and undeniable. He is widely regarded as the "father of iron sculpture," pioneering the use of welding as a primary technique for artistic creation. His concept of "drawing in space" opened up new possibilities for sculptural form, moving beyond solid mass to embrace linearity, transparency, and the dynamic interplay between material and void. This approach profoundly influenced the development of abstract sculpture in Europe and America.

The most significant inheritor of González's legacy was the American sculptor David Smith. Smith encountered González's work through reproductions in the early 1930s and immediately recognized the potential of welded metal. He adopted the technique and the open-form aesthetic, acknowledging González as his primary inspiration. Smith went on to become a leading figure in Abstract Expressionist sculpture, building upon González's innovations to create his own powerful and expansive body of work.

In Britain, sculptors associated with the "Geometry of Fear" movement, such as Lynn Chadwick and Reg Butler, as well as the later abstract sculptor Anthony Caro, also drew inspiration from González's direct metal techniques and open constructions, even as they developed their own distinct styles. Caro, in particular, acknowledged the importance of González and Picasso's welded works in his shift towards assembled abstract sculpture in the 1960s.

In Spain, González's influence can be seen in the work of Basque sculptors like Eduardo Chillida and Jorge Oteiza, who explored the spatial possibilities of iron and steel, albeit often with a greater emphasis on mass and volume than González's linear forms. Throughout Europe, artists like the Danish sculptor Robert Jacobsen embraced welded iron, contributing to the widespread acceptance of direct metal sculpture in the post-war era.

Beyond specific artists, González's work fundamentally changed attitudes towards materials and techniques. He demonstrated that industrial processes like welding could be sophisticated tools for artistic expression, bridging the perceived gap between craft and fine art. He elevated iron from a purely functional or decorative material to a primary medium for avant-garde sculpture. His legacy lies not only in his own remarkable sculptures but also in the doors he opened for future generations to explore the expressive potential of metal and space. His works are held in major museum collections worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Tate Modern in London, and the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid.

Conclusion: The Enduring Vision of Julio González

Julio González's journey from a traditional metalworker's son in Barcelona to a pioneering figure of the Parisian avant-garde is a testament to his unique vision and technical mastery. His late but decisive turn to welded iron sculpture revolutionized the medium, introducing the radical concept of "drawing in space" and demonstrating the expressive power of industrial materials and techniques. His collaboration with Picasso was a catalyst for his own development and contributed significantly to the history of modern sculpture.

Through works like La Montserrat, Woman Combing Her Hair, and the Cactus Man series, González explored themes of humanity, suffering, and resilience, creating sculptures that are both formally innovative and deeply moving. He proved that abstract forms could carry profound emotional weight and that the perceived coldness of iron could be transformed into lines of grace, tension, and tenderness.

His influence extended far beyond his own lifetime, shaping the work of major figures like David Smith and Anthony Caro and paving the way for the widespread acceptance of direct metal sculpture. Julio González remains a crucial figure for understanding the trajectory of twentieth-century art, an artist who skillfully forged a new path for sculpture, leaving behind a legacy etched in iron and air.