The Golden Age of Venetian Painting

The sixteenth century witnessed the zenith of painting in Venice, a city whose unique character—a wealthy maritime republic, a crossroads of trade, and a center of vibrant pageantry—found glorious expression on canvas. Alongside the towering figures of Titian and Tintoretto, Paolo Caliari, universally known as Paolo Veronese, formed the great triumvirate that dominated the Venetian art scene. Renowned for his luminous color, sprawling compositions, and depictions of magnificent feasts and celestial visions, Veronese captured the splendor and spirit of his adopted city, leaving behind a legacy of breathtaking beauty and artistic innovation.

From Verona to Venice: Early Life and Training

Paolo Caliari was born in Verona in 1528. Verona, though part of the Venetian Republic's mainland territories (the Terraferma), possessed its own distinct artistic traditions. His father, Gabriele, was a stonecutter (spezapreda), providing young Paolo with an early familiarity with materials and perhaps a sense of three-dimensional form. However, his artistic inclinations soon became apparent. His mother was the illegitimate daughter of a nobleman named Antonio Caliari, whose surname Paolo eventually adopted.

Recognizing his talent, Paolo did not follow his father's trade but was instead apprenticed around the age of fourteen to his uncle, Antonio Badile. Badile was a respected local painter in Verona, heading a busy workshop. Under Badile's tutelage, Veronese learned the fundamentals of drawing, composition, and the Veronese tradition's emphasis on clear outlines and bright, often decorative color, which owed something to earlier masters like Andrea Mantegna and Liberale da Verona. He also absorbed influences from prominent North Italian artists whose work could be seen in Verona, including Giulio Romano and perhaps Parmigianino, known for their sophisticated Mannerist elegance.

Even in his early Veronese works, such as the Bevilacqua-Lazise Altarpiece (c. 1548), Veronese demonstrated a precocious talent for handling complex figure groups and an emerging preference for lighter, more silvery tonalities than those typical of his master. He collaborated with other local artists, including Giovanni Battista Zelotti, who would remain an associate for some time. His burgeoning reputation soon extended beyond Verona.

Arrival and Ascent in the Floating City

Around 1553, Paolo Veronese made the pivotal move to Venice. The city was the undisputed artistic capital of the region, boasting a lineage that included Giovanni Bellini, Giorgione, and the already dominant Titian. For an ambitious young painter from the provinces, Venice offered unparalleled opportunities for patronage, exposure, and artistic dialogue. The environment was intensely competitive but also incredibly stimulating.

One of his earliest significant commissions in Venice came in 1551 (though likely completed after his definitive move) from the powerful Giustiniani family. He was tasked with painting an altarpiece for their chapel in the church of San Francesco della Vigna. This work, depicting the Holy Family with Saints Catherine, Anthony Abbot, and the Infant John the Baptist, already shows his characteristic clear light and harmonious color palette, distinguishing him from the more dramatic chiaroscuro favored by some contemporaries.

His talents were quickly recognized. He worked on decorative schemes outside Venice, notably at the Villa Soranzo near Treviso around 1551, alongside Zelotti and Anselmo Canerio. Though these frescoes survive only in fragments, contemporary accounts praised their beauty and illusionism, helping to establish Veronese's name. By the mid-1550s, he was receiving prestigious commissions within Venice itself.

Securing a Place: San Sebastiano and the Doge's Palace

A defining relationship began in 1555 when Veronese started working for the church of San Sebastiano in Venice. This association would last for decades, resulting in the church becoming a veritable museum of his art. He began with paintings for the sacristy ceiling, followed by canvases for the main nave ceiling depicting scenes from the Book of Esther (1556). These works showcased his developing mastery of sotto in sù perspective (figures seen from below) and his ability to orchestrate complex narratives within challenging formats.

His work at San Sebastiano continued with frescoes on the upper walls, an altarpiece depicting the Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints, and paintings for the organ shutters showing the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple and Christ Healing the Pool of Bethesda. His dedication to this church was profound; he would eventually choose to be buried there, surrounded by his own creations. The vibrant colors, dynamic compositions, and elegant figures solidified his reputation as a major force.

Simultaneously, Veronese secured commissions in the heart of Venetian power: the Doge's Palace. Around 1553-1554, he contributed ceiling paintings to the Sala dei Dieci (Hall of the Council of Ten), including the stunning Juno Showering Gifts on Venetia. His success led to further work in the palace, particularly after a fire in 1577 destroyed works by previous masters like Gentile da Bellini and Titian. Veronese played a key role in the redecoration, contributing works like the vast ceiling painting The Triumph of Venice in the Sala del Maggior Consiglio (Hall of the Great Council), a complex allegory celebrating the glory of the Republic. These state commissions demanded grandeur, clarity, and often intricate allegorical programs, skills Veronese possessed in abundance.

The Venetian Triumvirate: Veronese, Titian, and Tintoretto

By the late 1550s and early 1560s, Veronese stood alongside Titian and Tintoretto as one of the three preeminent painters in Venice. Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), the eldest and most internationally famous, was renowned for his profound humanism, mastery of color and texture, and psychologically penetrating portraits. Tintoretto (Jacopo Robusti), known for his dramatic energy, rapid brushwork, and intense spiritual fervor, represented a more Mannerist, emotionally charged approach.

Veronese offered a distinct alternative. While deeply influenced by Titian's handling of color, Veronese developed a palette characterized by its luminosity, clarity, and harmonious juxtaposition of hues. He favored bright, silvery light that bathed his scenes, unlike Tintoretto's often stormy and mystical illumination. His compositions, though complex and crowded, typically possess an underlying structure and balance, often employing grand architectural settings inspired by contemporary architects like Jacopo Sansovino and Andrea Palladio.

While Tintoretto explored deep spiritual drama and Titian plumbed psychological depths, Veronese excelled at depicting worldly splendor, festive gatherings, and celestial pageantry. His figures, often clad in luxurious contemporary Venetian attire, move with an effortless grace (sprezzatura). He brought a sense of joyous celebration even to religious subjects, emphasizing the magnificence of the divine through the richness of the earthly. There was rivalry among the three, but also mutual respect; Veronese reportedly admired Tintoretto's drawing skill, while Tintoretto praised Veronese's color. Together, they defined the visual language of late Renaissance Venice.

Collaboration with Palladio: The Villa Barbaro

A unique and highly significant commission came around 1560-1561 when Veronese was invited to decorate the Villa Barbaro at Maser. This villa, designed by the great architect Andrea Palladio for the cultivated Barbaro brothers, Daniele and Marcantonio, is a masterpiece of Renaissance architecture, blending classical ideals with Venetian traditions. Veronese's frescoes cover the walls and ceilings of the main rooms, creating one of the most harmonious integrations of painting and architecture of the era.

Working within Palladio's classically proportioned spaces, Veronese created a complex decorative scheme that includes mythological scenes, allegorical figures, illusionistic landscapes glimpsed through painted windows, and even portraits of the Barbaro family members and their household staff appearing as if part of the scene. The frescoes display Veronese's wit, his mastery of perspective and illusion (trompe-l'oeil), and his ability to create a world of serene, idealized beauty. The collaboration between Palladio and Veronese at Maser remains a high point of Renaissance culture, embodying the humanist ideal of harmony between art, architecture, and nature.

The Great Feast Paintings: Spectacle and Controversy

Veronese is perhaps most famous for his enormous canvases depicting biblical feasts, rendered as sumptuous Venetian banquets. The first and most celebrated of these is The Wedding at Cana (1563), painted for the refectory of the Benedictine monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice. Measuring nearly 7 by 10 meters, it is one of the largest paintings of the Renaissance. Veronese transforms the biblical miracle into a spectacular contemporary feast, crowded with over 130 figures, including musicians (portraits of Titian, Tintoretto, Bassano, and Veronese himself are traditionally identified), servants, guests in lavish attire, animals, and elaborate architectural details under a clear, bright sky. The painting is a tour-de-force of organization, color, and detail, celebrating both divine power and worldly magnificence. Confiscated by Napoleon in 1797, it now dominates a wall in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

Ten years later, in 1573, Veronese painted another vast feast scene, originally titled The Last Supper, for the refectory of the Dominican friars at Santi Giovanni e Paolo in Venice. This work, however, led to a famous confrontation with the Inquisition. The Counter-Reformation Church was becoming increasingly strict about the depiction of religious subjects, and the tribunal questioned Veronese about the inclusion of figures they deemed inappropriate for the solemnity of the Last Supper: dogs, dwarfs, jesters, German soldiers (associated with Protestantism), and other seemingly extraneous details.

Veronese's defense, recorded in the tribunal transcript, is a fascinating assertion of artistic license. He argued that painters took the same liberties as poets and madmen, that he added figures "for ornament," and that he conceived the scene as taking place in a grand, wealthy household where such attendants would be present. He cited Michelangelo's inclusion of nudes in the Sistine Chapel as precedent. While respectful, he refused to fundamentally alter his artistic vision. The tribunal ultimately ordered him to "correct" the painting within three months at his own expense. Veronese cleverly circumvented this by simply changing the title to The Feast in the House of Levi, referencing a different biblical banquet hosted by the tax collector Levi (Matthew) for Christ, which allowed for a more diverse and worldly gathering. The painting, now housed in Venice's Gallerie dell'Accademia, stands as a testament to Veronese's artistic integrity and his unparalleled ability to stage grand, multi-figure narratives.

Other Masterworks: Mythologies, Allegories, and Devotion

Beyond the famous feast paintings, Veronese produced a wealth of works across various genres. He excelled in mythological subjects, often imbued with sensuousness and elegance. Notable examples include the Allegories of Love (c. 1575), a series of four paintings likely commissioned by Emperor Rudolf II, depicting themes like Infidelity and Respect (now in the National Gallery, London). His Mars and Venus United by Love (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) is a harmonious composition celebrating love's power, rendered in his signature silvery tones and rich textures.

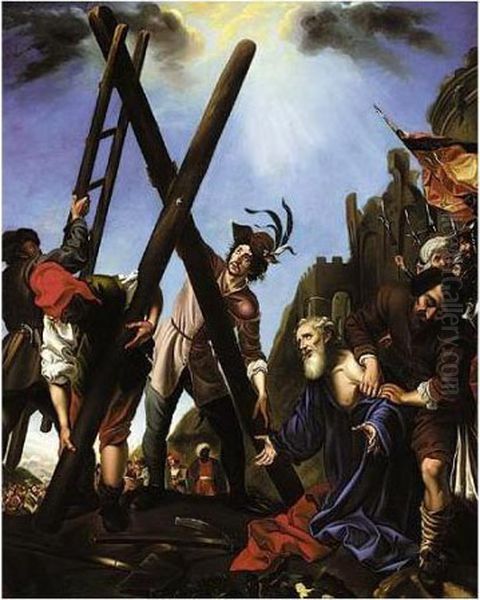

He continued to produce major altarpieces and devotional works throughout his career. The Martyrdom of Saint George (c. 1564), painted for the church of San Giorgio in Braida, Verona, is a dynamic and dramatic composition. The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine (c. 1575, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice) is celebrated for its radiant color and tender emotion. He also painted portraits, though they form a smaller part of his output compared to Titian's. His Portrait of a Gentleman (Palazzo Pitti, Florence) shows his ability to capture likeness with dignity and refined detail.

His decorative talents remained in demand. He contributed to numerous palaces and villas, often creating allegorical ceiling paintings that celebrated the virtues or lineage of the patrons. His style, adaptable yet always recognizable, suited the opulent tastes of the Venetian elite.

The Veronese Workshop: A Family Enterprise

Like many successful Renaissance artists, Veronese maintained a large and active workshop to help manage the scale and number of his commissions. Unusually, his workshop was primarily a family affair. His younger brother, Benedetto Caliari (1538–1598), was a painter in his own right and a key collaborator, particularly skilled in architectural perspectives. Veronese's sons, Carlo (or Carletto) Caliari (1570–1596) and Gabriele Caliari (1568–1631), also became painters and worked closely with their father. Another relative, Luigi Benfatto (also called Alvise dal Friso, 1554–1611), was also part of the studio.

The workshop operated collaboratively. Veronese would typically create the initial designs and sketches (modelli) and oversee the execution, often painting key passages himself, especially faces and important figures. Assistants would then work on backgrounds, drapery, architectural elements, and secondary figures under his supervision. This system allowed for efficient production of the enormous canvases and fresco cycles he undertook.

After Veronese's death in 1588, the workshop continued to operate for at least a decade under the direction of his brother and sons. They completed unfinished commissions and produced new works in his style, often signing them collectively as "Haeredes Pauli Caliari Veronensis" (The Heirs of Paolo Caliari Veronese). While these later works sometimes lack the master's ultimate finesse, they testify to the strength and coherence of the style Veronese established and the loyalty of his family collaborators. Other pupils and associates included Giovanni Antonio Fasolo and Antonio Vassilacchi (l'Aliense), who went on to have independent careers.

Later Years, Death, and Enduring Legacy

Veronese remained active and highly sought after until the end of his life. His later works sometimes show a slightly looser brushwork and occasionally a more somber or nocturnal lighting, perhaps reflecting the influence of Tintoretto or changing tastes, but his fundamental commitment to rich color and harmonious composition remained. He continued to receive important commissions, including further work in the Doge's Palace after the 1577 fire.

In April 1588, after catching a fever while participating in a religious procession in Treviso, Paolo Veronese died of pneumonia in Venice. He was sixty years old. He was buried, as he wished, in the church of San Sebastiano, the site of so many of his artistic triumphs.

Veronese's influence was immediate and lasting. His emphasis on color and light profoundly impacted subsequent Venetian painters like Palma il Giovane and, much later, Giambattista Tiepolo, who revived Veronese's grand decorative manner in the 18th century. His work was admired and studied by artists across Europe. Peter Paul Rubens, the great Flemish Baroque master, was particularly indebted to Veronese's color, compositional energy, and opulent style. Anthony van Dyck also learned from his elegance. Artists like Charles Le Brun in France and later Rococo painters such as Jean-Antoine Watteau, François Boucher, and Jean-Honoré Fragonard looked to Veronese's festive scenes and luminous palette. Even Diego Velázquez, during his visits to Italy, studied Veronese's work, absorbing lessons in color and composition.

Veronese's Art in the Modern World

Today, Paolo Veronese's works are found in major museums and collections worldwide, as well as remaining in situ in the churches and palaces of Venice and the Veneto for which they were created. The Louvre in Paris, the Gallerie dell'Accademia in Venice, the National Gallery in London, the Prado Museum in Madrid, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York all hold significant examples of his paintings.

Many of his works, particularly the large canvases and frescoes, have undergone restoration over the centuries to address issues like darkening varnish, accumulated dirt, or past damages. The restoration of The Wedding at Cana in the 1990s was a major international project. Similarly, works like the Madonna Enthroned with Saints (originally from San Zaccaria, now Accademia) and the Rape of Europa (Doge's Palace) have benefited from careful conservation efforts that reveal the original brilliance of Veronese's colors. These efforts ensure that future generations can experience the splendor of his vision.

Conclusion: The Painter of Splendor

Paolo Veronese stands as one of the giants of the Venetian Renaissance, a master whose art embodies the unique spirit of his adopted city – its wealth, its pageantry, its love of color and light. He possessed an unparalleled ability to organize vast, complex compositions teeming with life, yet imbued with harmony and grace. His luminous palette, characterized by cool, silvery tones alongside rich jewel-like hues, created a world of dazzling visual delight.

Whether depicting sacred miracles, mythological dramas, or allegorical celebrations, Veronese infused his subjects with a sense of magnificent spectacle. His famous feast scenes are not merely illustrations of biblical events but vibrant celebrations of life itself, rendered with astonishing detail and chromatic brilliance. His confrontation with the Inquisition highlighted the tension between artistic freedom and religious orthodoxy in the Counter-Reformation era, showcasing his quiet defense of his creative vision. Through his prolific output, his influential workshop, and his lasting impact on subsequent generations of artists, Paolo Veronese secured his place as the great painter of splendor in the golden age of Venetian art.