The late Victorian and Edwardian eras in Britain witnessed a flourishing of artistic talent, particularly in the medium of watercolour. Among the many artists who captured the architectural heritage and literary landscapes of the period, Paul Braddon (1864-1938) holds a distinct, if sometimes overlooked, position. Operating under a pseudonym, his true identity being James Leslie Crees, Braddon carved a niche for himself with his evocative and meticulously detailed depictions of cathedrals, historic cityscapes, and sites imbued with literary significance. His work not only serves as a visual record of his time but also reflects the prevailing tastes and cultural preoccupations of a nation grappling with modernity while cherishing its past.

It is important at the outset to clarify a point of potential confusion that sometimes arises. The artist Paul Braddon, James Leslie Crees, is entirely distinct from Paul E. Bragdon, who served as the president of Reed College in the United States much later in the 20th century (1971-1988). The artist Braddon's life and work were firmly rooted in the British art scene of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a world away from American academia. This distinction is crucial for an accurate appreciation of his artistic contributions.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis of James Leslie Crees

James Leslie Crees was born in Birmingham in 1864. Birmingham, a powerhouse of the Industrial Revolution, was a city of stark contrasts – of burgeoning industry and wealth, but also of crowded urban living. This environment, perhaps, fostered an appreciation for the enduring beauty and historical gravitas of older structures and more picturesque landscapes, which would later become central to his artistic output. While specific details about Crees's early art education are not extensively documented, it is evident from his later proficiency that he received solid training in draughtsmanship and watercolour technique.

The Victorian era placed a high value on skill and verisimilitude in art. The Royal Academy and numerous regional art schools emphasized rigorous training in drawing. It is likely Crees benefited from such an environment, whether through formal schooling or apprenticeship. His early works, as noted, included sketches of European cathedrals and churches. This suggests a period of travel or at least a dedicated study of architectural forms, possibly inspired by the grand tradition of the architectural tour that had been popular since the 18th century, albeit evolving with increased accessibility to travel. Artists like Samuel Prout (1783-1852) and David Roberts (1796-1864) had, in earlier generations, set a high standard for picturesque architectural views from across Britain and Europe, and their influence on the genre was pervasive.

The decision to adopt the pseudonym "Paul Braddon" is not uncommon in the art world. Artists sometimes choose alternative names for marketability, to distinguish different styles or periods of their work, or simply for personal preference. Under this adopted name, Crees would build his reputation.

The Ascendancy of Watercolour and Braddon's Stylistic Approach

Paul Braddon's chosen medium, watercolour, enjoyed immense popularity in 19th-century Britain. The Royal Watercolour Society and the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours were prestigious institutions, and the medium was favored for its portability, luminosity, and suitability for capturing atmospheric effects and intricate details. Artists like J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851), though working on a far grander and more revolutionary scale, had elevated watercolour to a high art form. Later Victorian watercolourists such as Myles Birket Foster (1825-1899), known for his charming rustic scenes, and Helen Allingham (1848-1926), celebrated for her depictions of quintessential English cottages and gardens, demonstrated the medium's versatility and appeal to a wide audience.

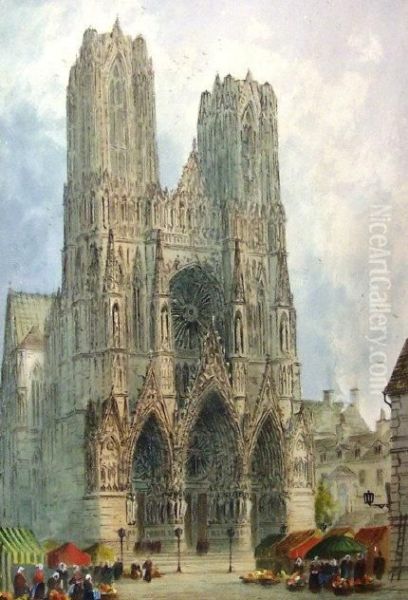

Braddon's style, while rooted in the topographical tradition, developed a distinctive character. His early focus on sketching European cathedrals and churches provided a strong foundation in architectural rendering. Even as he transitioned more fully to watercolour, this "architectural consciousness," as some sources describe it, remained a hallmark of his work. His paintings often possess the precision and clarity of an architect's drawing, yet they are imbued with an artistic sensibility that transcends mere technical representation. He had a keen eye for the play of light and shadow on stone, the textures of aged materials, and the overall atmosphere of a place.

His technique often involved careful preliminary drawing, followed by washes of colour that built up form and depth. While some contemporaries might have pursued a looser, more impressionistic style, Braddon generally maintained a high degree of finish and detail, which appealed to the Victorian appreciation for craftsmanship. His street scenes, for instance, are not just general impressions but are often populated with recognizable buildings and a sense of the daily life of the era, captured with a certain nostalgic charm.

Dominant Themes in Braddon's Oeuvre

Paul Braddon's thematic concerns were well-defined and catered to the interests of his time, focusing primarily on architectural grandeur and sites of literary and historical importance.

Architectural Grandeur: Cathedrals and Cityscapes

Cathedrals and significant ecclesiastical buildings were a recurring subject for Braddon. These structures, often centuries old, represented continuity, spiritual aspiration, and national heritage. His depictions of these edifices, whether British or Continental, emphasized their scale, intricate details (such as Gothic tracery or Romanesque carving), and the way they dominated their surroundings. Works like his views of Canterbury Cathedral, York Minster, or Westminster Abbey would have resonated deeply with a public proud of its historical and architectural legacy. The Gothic Revival, championed by architects like Augustus Pugin (1812-1852) and writers like John Ruskin, had instilled a profound appreciation for medieval architecture, and Braddon's work tapped into this sentiment.

Beyond individual monuments, Braddon also excelled at capturing broader cityscapes and street scenes, particularly of London. These works often highlight historic buildings nestled within the evolving urban fabric. He painted views of well-known thoroughfares, ancient inns, and notable public buildings, preserving a visual record of London as it was in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His ability to combine architectural accuracy with a sense of atmosphere made these urban portraits particularly engaging. One can imagine his contemporaries, artists like William Logsdail (1859-1944) or the Italian-born Giuseppe de Nittis (1846-1884) who painted London scenes, working within a similar milieu, though often with different stylistic emphases.

Literary Landscapes: Shakespeare and Beyond

A significant portion of Paul Braddon's output was dedicated to sites associated with major literary figures, most notably William Shakespeare. The late Victorian era saw a fervent interest in Shakespeare, not just his plays but also his life and the places connected to him. Stratford-upon-Avon became a site of pilgrimage, and images of Shakespeare's Birthplace, Anne Hathaway's Cottage, Holy Trinity Church, and New Place were immensely popular.

Braddon produced numerous watercolours of these locations, often characterized by their topographical accuracy and charming detail. These works, created around the 1890s, found a ready market and were disseminated through various means, including publications and, as evidenced by the "Shakespeare Homes and Haunts Wall Calendar 2025," through popular print culture even into the modern day. The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust holds a collection of these works, underscoring their historical and cultural value. His depictions are not merely illustrative but seek to evoke the spirit of the Elizabethan era, often with a slightly romanticized, picturesque quality. This interest in literary shrines was shared by other artists; for example, Helen Allingham also painted charming views in and around Stratford-upon-Avon.

Braddon's literary interests extended beyond Shakespeare. He is known to have designed a memorial plaque for a house in Cambridge where the essayist Charles Lamb had lived. This act suggests a personal engagement with literary history and a desire to commemorate these connections through visual means. His monochrome watercolour, "The Clock House, Edmonton," likely also ties into local history or literary associations, as Edmonton had connections to Lamb and John Keats. Such works highlight the Victorian fascination with the biographies of great writers and the physical spaces they inhabited.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Prolific Output

Paul Braddon was a prolific artist. The exhibition at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery in New Zealand, which featured 58 of his "locality paintings," attests to the reach of his work, extending even to the colonies of the British Empire. Such exhibitions were crucial for an artist's reputation and sales. While he may not have been a consistent exhibitor at the Royal Academy like some of his more famous contemporaries, his work found an appreciative audience.

The nature of his subjects – recognizable landmarks, picturesque views, and literary shrines – made his art accessible and desirable to a broad public, including the burgeoning middle class who sought to adorn their homes with pleasing and culturally resonant images. His watercolours were likely sold through dealers, in smaller galleries, and possibly through direct commissions. The fact that his Shakespearean scenes were used for calendars indicates a commercial astuteness and an understanding of the popular market for art.

His output, often characterized by a consistent style and subject matter, suggests a dedicated and industrious career. While perhaps not an innovator in the mould of the Impressionists or Post-Impressionists who were challenging artistic conventions during his lifetime, Braddon excelled within his chosen tradition. He provided a valuable service in documenting the architectural and cultural landscape of Britain at a time of significant change. Artists like Albert Goodwin (1845-1932), another prolific watercolourist known for his atmospheric landscapes and city views, often with literary or historical allusions, occupied a similar space in the art market, appealing to a taste for the picturesque and the poetic. Similarly, the detailed architectural studies of Axel Haig (1835-1921), a Swedish-born etcher and watercolourist who worked in Britain, share some common ground with Braddon's meticulous approach to buildings.

The Broader Artistic Context

To fully appreciate Paul Braddon's contribution, it's helpful to consider the wider artistic currents of his time. The late 19th century was a period of diverse artistic expression. While the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood had earlier championed a return to detailed realism and literary themes, their direct influence was waning by Braddon's active period. However, their emphasis on truth to nature and narrative content had left a lasting mark on Victorian taste.

The Aesthetic Movement, with figures like James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), promoted "art for art's sake," focusing on beauty and formal qualities over narrative. While Braddon's work was more representational and topographical, the general Victorian appreciation for beauty and skilled craftsmanship provided a supportive environment. The rise of photography also had an impact on painting. Some artists embraced it as a tool, while others, perhaps like Braddon, emphasized the unique qualities of hand-painted art – its colour, texture, and the artist's individual interpretation – to distinguish their work from mechanical reproductions.

The interest in national heritage, evident in Braddon's choice of subjects, was a strong cultural trend. Organizations like the National Trust (founded in 1895) were emerging, dedicated to preserving places of historic interest and natural beauty. Braddon's art, in its own way, contributed to this preservationist impulse by creating enduring visual records of these sites. His work can be seen alongside that of other topographical artists of the period, such as Ernest George (1839-1922), an architect who was also a skilled watercolourist and etcher of picturesque old buildings, or Wilfrid Ball (1853-1917), known for his charming watercolours and etchings of English landscapes and historic towns.

Legacy and Lasting Appeal

Paul Braddon (James Leslie Crees) passed away in 1938, on the cusp of another world war that would irrevocably change Britain and the world. His art, however, remains a window into a preceding era. His legacy lies in his dedicated and skillful portrayal of architectural and literary landmarks. While he may not be as widely celebrated as some of his more avant-garde contemporaries, his work holds considerable charm and historical value.

His watercolours serve as important documents, capturing the appearance of buildings and streetscapes, some of which may have since been altered or lost. For social historians and those interested in architectural history, his paintings offer valuable visual information. For lovers of literature, his depictions of Shakespearean haunts provide a tangible connection to the writer's world, filtered through a late Victorian sensibility.

The continued interest in his work, as seen in the production of items like the Shakespeare calendar, demonstrates its enduring appeal. His art speaks to a nostalgia for a seemingly more settled and picturesque past, an appreciation for craftsmanship, and a fondness for the historical and literary heritage of Britain. In an age of rapid digital imagery, the handcrafted quality and gentle atmosphere of a Paul Braddon watercolour offer a quiet and reflective pleasure. His contribution, though perhaps modest when compared to the giants of art history, is a significant one within the tradition of British watercolour painting and topographical art. He was a diligent chronicler of his nation's heritage, leaving behind a body of work that continues to delight and inform. Artists like Charles Edward Brittan (1837-1888) or Sutton Palmer (1854-1933), who also specialized in picturesque British landscapes and historic scenes in watercolour, belong to this same tradition of artists who catered to and helped shape the public's appreciation for the beauty of their homeland.

In conclusion, Paul Braddon, the nom de plume of James Leslie Crees, was an accomplished British watercolourist whose career spanned a period of significant cultural and artistic activity. His meticulous and atmospheric depictions of cathedrals, historic cityscapes, and literary landmarks, particularly those associated with Shakespeare, have secured him a place in the annals of British topographical art. His work reflects the Victorian and Edwardian fascination with history, architecture, and literature, and continues to be valued for its artistic merit and as a charming visual record of a bygone era.